Abstract

Background

Epidemiological studies have suggested an association between selenium (Se) and diabetes mellitus (DM). However, different studies have reported conflicting results. Therefore, we performed a comprehensive meta-analysis to clarify the impact of Se on DM.

Methods

We searched the PubMed database for studies on the association between Se and DM from inception to June 2018.

Results

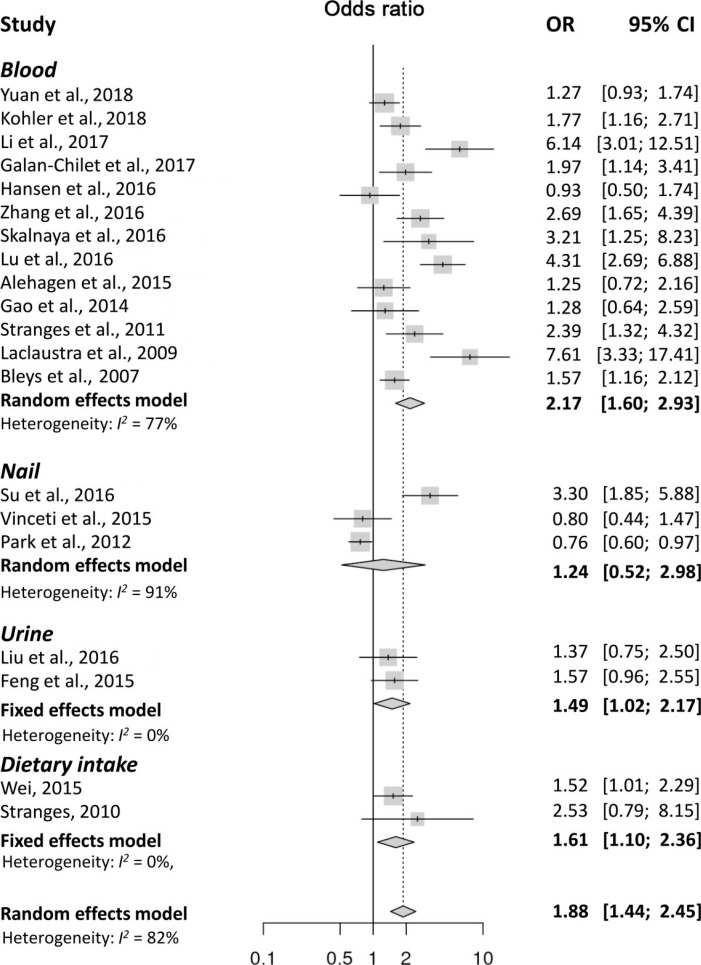

Twenty articles evaluating 47,930 participants were included in the analysis. The meta-analysis found that high levels of Se were significantly associated with the presence of DM (pooled odds ratios [ORs], 1.88; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.44 to 2.45). However, significant heterogeneity was found (I2=82%). Subgroup analyses were performed based on the Se measurement methods used in each study. A significant association was found between high Se levels and the presence of DM in the studies that used blood (OR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.60 to 2.93; I2=77%), diet (OR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.10 to 2.36; I2=0%), and urine (OR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.02 to 2.17; I2=0%) as samples to estimate Se levels, but not in studies on nails (OR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.52 to 2.98; I2=91%). Because of significant heterogeneity in the studies with blood, we conducted a sensitivity analysis and tested the publication bias. The results were consistent after adjustment based on the sensitivity analysis as well as the trim and fill analysis for publication bias.

Selenium (Se) is an integral component of selenocysteine, a major structural amino-acid of selenoproteins [1]. In addition to its anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, Se is also involved in the synthesis of DNA and thyroid hormone [1]. The cytoprotective properties of selenoproteins have garnered much interest leading to the discovery of selenoenzymes such as glutathione peroxidase (GPx), thioredoxin reductase (TrxR), and iodothyronine deiodinases (IDDs) [2]. GPx, which is one of the most well-studied selenoprotein family members, functions as a part of a defense mechanism to protect polyunsaturated fatty acids from the damaging effects of free radicals and inhibits the production of proinflammatory cytokines, reactive oxygen species, and reactive nitrogen species [3].

Due to the anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory properties of Se, numerous studies have assessed the relationship between Se levels and conditions commonly known to be associated with increased oxidative stress and inflammation such as cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases, diabetes mellitus (DM), and cancer [456]. The association between Se and DM is one of the most vigorously investigated [78]. Studies have mainly been conducted based on the assumption that Se may be protective against DM [9]. Oxidative stress and inflammation have been reported to be involved in the onset and progression of diabetes [1011]. Consistent with these findings, supplementation of antioxidants including Se has been shown to delay the onset of DM [6]. Moreover, data from isolated rat adipocytes show that Se in the form of selenate can act as an insulin mimetic [1213]. Several cell and animal studies have suggested that Se plays a crucial role in controlling glucose homeostasis [14151617]. Moreover, epidemiological studies have evaluated the effects of Se on DM, but the conclusions have been conflicting [181920212223]. Some studies report that Se is positively associated with DM [181920] while others indicate a negative or no association [212223]. Although there has been a meta-analysis including five observational studies [7], many additional studies have been published since then [18192425]. Hence, an updated meta-analysis to review the recent data is warranted to understand better and clarify the role of Se in DM. Therefore, we performed an updated meta-analysis by a comprehensive investigation of the literature with conflicting conclusions.

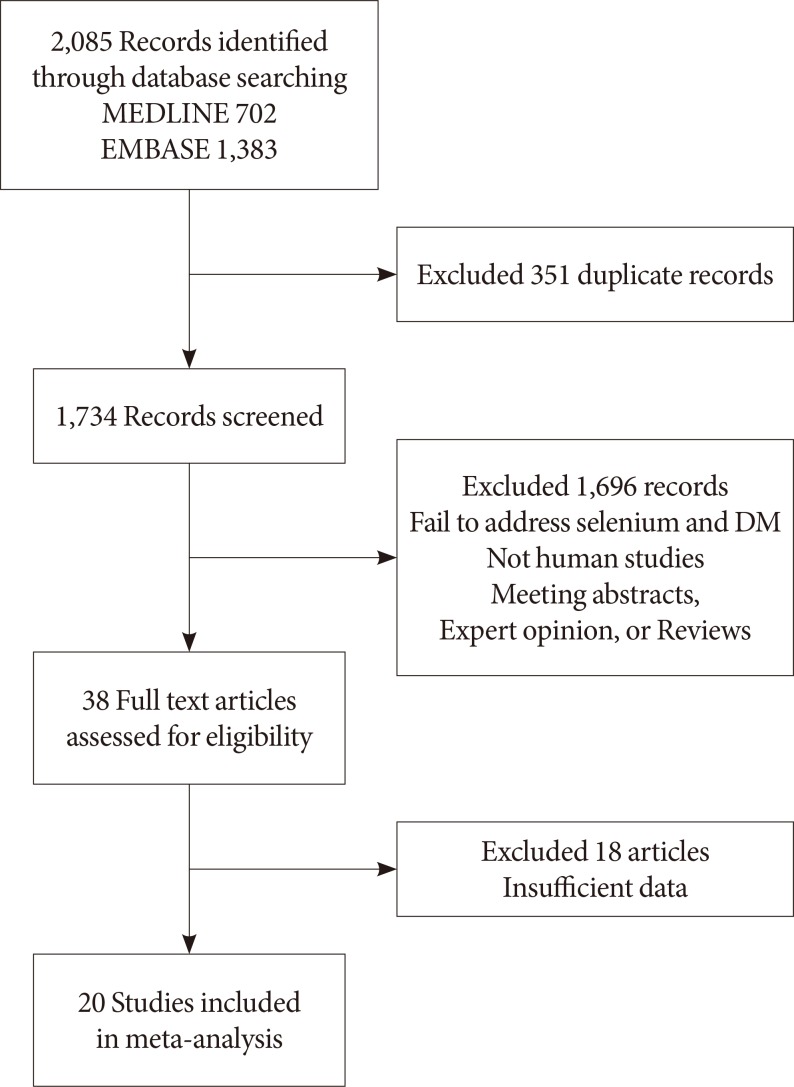

The literature search was performed in accordance with the general principles recommended in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Supplementary Table 1). Two independent investigators (S.M. and J.K.) searched the PubMed and Embase databases and selected articles using a combination of terms “diabetes mellitus” and “selenium.” Only articles published in English, before June 30, 2018, were included.

The literature search yielded 2,085 potentially relevant articles, of which 1,734 were screened for further review after excluding duplicate studies. If studies had multiple reports, the latest or the complete article was enrolled. All articles were electronically downloaded and screened for inclusion using a two-step method. After evaluation of the titles and abstracts according to predefined criteria, 1,696 articles were excluded if: (1) the studies had a different topic of interest; (2) there was no information on Se and DM; or (3) the study was published as an abstract, expert opinion, conference article, or review. Subsequently, the full texts of 38 selected articles were reviewed by two independent investigators (S.M. and J.K.), and any disagreement was resolved by a third investigator (J.M.Y.). A total of 20 articles were finally selected for the meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Three researchers independently assessed the methodological quality of the included articles using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for case control studies [26]. Nine items were used to assess the quality, and all articles scored 6 to 8 (Supplementary Table 2). We concluded that the quality of these cross-sectional studies did not affect the quality of our meta-analysis.

The following variables were independently extracted by the two investigators based on the same rules: first author, publication year, country, number of study participants, mean age, number of men and women, characteristics of study participants including coexisting diseases, the mean or median concentration of Se, and number of DM.

We calculated the pooled odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the highest and lowest quantiles of Se using the Mantel-Haenszel method. The Higgins' I2 statistic was used to test for heterogeneity. When I2 was ≤50%, the included studies were considered to have little heterogeneity, and a fixed-effects model was used. However, I2 >50% indicated heterogeneity and a random-effects model was used. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses were used to determine the cause of heterogeneity. The potential for publication bias was assessed by funnel plot analysis. To examine the strength of the outcome, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to estimate the effects of the remaining studies without the larger one. All statistical analyses were calculated using the statistical program R (R version 3.1.0, 2014, www.r-project.org).

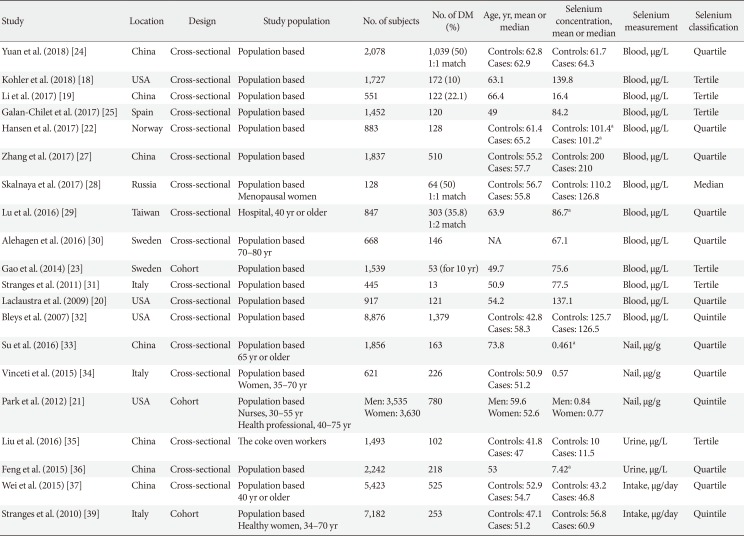

Twenty articles were included in the meta-analysis [1819202122232425272829303132333435363738], and their main characteristics are summarized in Table 1. In total, 47,930 participants were enrolled, and 6,347 of them had DM. Sample sizes of these studies ranged from 128 to 8,876 participants. In these studies, Se concentrations were measured in the blood (n=13), nails (n=3), and urine (n=2). Two studies estimated Se intake from a food diary survey.

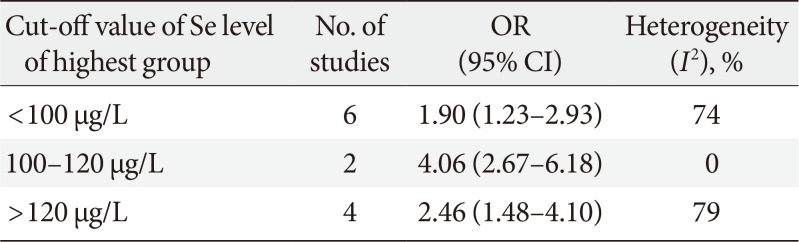

The meta-analysis found that high levels of Se were significantly associated with the presence of DM (OR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.44 to 2.45). However, there was significant heterogeneity (I2=82%) (Fig. 2), and the funnel plot analysis showed significant publication bias (Supplementary Fig. 1). In the sensitivity analysis, the pooled OR changed little after omitting each study (Supplementary Fig. 2), and the heterogeneity ranged from 1.99 to 2.31, remaining statistically significant. A subgroup analysis based on the methods used for Se measurements, showed a significant association between high Se levels and DM in the studies on blood (OR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.60 to 2.93; I2=77%), dietary intake (OR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.10 to 2.36; I2=0%), and urine (OR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.02 to 2.17; I2=0%). However, studies on Se in the nails failed to show a significant association with DM (OR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.52 to 2.98; I2=91%). Because a significant heterogeneity was found in studies with blood, we conducted a sensitivity analysis and tested the publication bias. Sensitivity analysis found three outlier studies [343536]. After omitting these studies, the estimated pooled OR was 1.64 (95% CI, 1.34 to 2.02) with no significant heterogeneity (I2=40.3%). Since the funnel plot was asymmetric, publication bias was adjusted using the trim-and fill method by adding two estimated missing studies, which produced significant results (OR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.31 to 2.53). Because of the heterogeneity in Se levels in each study, we conducted a subgroup analysis based on the mean or median blood Se levels, using 100 µg/L as the cut-off value. The pooled OR was 2.17 (95% CI, 1.37 to 3.44; I2=82%) in studies with mean Se <100 µg/L and 2.17 (95% CI, 1.40 to 3.39; I2=76%) in studies with mean Se ≥100 µg/L. A meta-regression analysis showed no significant effects of the mean Se levels (P=0.91) (Supplementary Fig. 3). The subgroup analysis using cut-off levels of Se of the highest group showed similar results (Table 2).

This meta-analysis of 20 observational studies showed that higher concentrations of Se were significantly associated with the presence of DM. Although significant heterogeneity was detected, the results did not change after adjustment by subgroup analysis, sensitivity analysis, and trim and fill analysis for publication bias.

DM is characterized by peripheral insulin resistance, with defects in insulin-secretion, which can be of varying degrees of severity. Although the mechanisms that underlie insulin resistance and diabetes are not fully understood, several studies point to the role of oxidative stress in the onset and progression of DM [10]. Therefore, Se which has been long touted for its antioxidant properties was believed to prevent the onset of DM by counteracting oxidative stress [9]. Although earlier studies have shown the insulin-mimetic and anti-diabetic effects of Se [1639], recent experimental studies have revealed an unexpected association between high Se intake and insulin resistance or DM [4041424344]. High Se exposure led to insulin resistance in rodents and pigs [45]. Although the mechanism underlying the diabetogenic effects of Se remains unclear, the high Se exposure might affect the expression of key regulators of glycolysis and gluconeogenesis. This action might potentially be mediated by the selenoprotein GPx-1 [45], as demonstrated by studies showing that overexpression of GPx-1 causes insulin resistance [46]. In skeletal muscles of pigs, high Se exposure led to an increase in GPx activity and expression of both forkhead box O1 and peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α genes. It also led to a decrease in the expression of the gene for the glycolytic enzyme pyruvate kinase [44].

A number of human studies have been conducted to evaluate the effects of Se on DM, but the conclusions have been inconsistent. Although previous meta-analyses showed a modest association between Se and DM, they included only five observational studies [7]. Therefore, this meta-analysis is noteworthy since it demonstrates an association between Se and the presence of DM based on a number of observational studies in large populations, providing significant epidemiological evidence to support the results of previous experimental studies.

Although our findings suggest that there is a significant association between increased exposure to Se and DM, data from clinical trials of Se supplementation have not been conclusive. The first large randomized trial was the Nutritional Prevention of Cancer (NPC) Trial, in which 200 µg Se per day or a matched placebo was administered to evaluate whether it could reduce the risk of non-melanoma skin cancer. Stranges et al. [47] performed the secondary analyses with the NPC data and showed an increased risk of DM among those in the Se intervention group compared to those in the placebo group. In contrast to the NPC trial, the Se and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT), the largest prostate cancer prevention trial with 35,533 participants showed no significant increase in the risk for DM after supplementation with 200 µg/day of Se compared to placebo [48]. However, in a subgroup analysis with the elderly aged >63 years, a significantly increased risk for DM was reported [49]. Mao et al. [8] on the other hand, showed no association between Se supplementation (200 µg/day) and the risk for DM in their meta-analysis with four randomized controlled trial studies.

The considerable strengths of this study are that a number of observational studies with large populations were included, and predefined subgroup analyses could be performed. However, the present study has some limitations. First, since most of the included studies were cross-sectional studies, further prospective studies will be needed to clarify the relationship between Se and the risk for DM. Second, the differences in age, sex ratio and Se concentrations between different studies could induce a bias. In addition, the different methods used for measuring Se levels could also have contributed to the bias. Third, because we compared the highest quantile of Se to the lowest quantile in each study, there might be great heterogeneity among the cases and control groups between different studies.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis demonstrates that high levels of Se are associated with the presence of DM. Although the mechanism remains unclear, our findings could have implications for nutritional supplementation in clinical settings. Further prospective and randomized controlled trials are warranted to elucidate the link between Se and DM better.

References

1. Mehdi Y, Hornick JL, Istasse L, Dufrasne I. Selenium in the environment, metabolism and involvement in body functions. Molecules. 2013; 18:3292–3311. PMID: 23486107.

2. Tapiero H, Townsend DM, Tew KD. The antioxidant role of selenium and seleno-compounds. Biomed Pharmacother. 2003; 57:134–144. PMID: 12818475.

3. Rohr-Udilova N, Sieghart W, Eferl R, Stoiber D, Bjorkhem-Bergman L, Eriksson LC, Stolze K, Hayden H, Keppler B, Sagmeister S, Grasl-Kraupp B, Schulte-Hermann R, Peck-Radosavljevic M. Antagonistic effects of selenium and lipid peroxides on growth control in early hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2012; 55:1112–1121. PMID: 22105228.

4. Nève J. Selenium as a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases. J Cardiovasc Risk. 1996; 3:42–47. PMID: 8783029.

6. Steinbrenner H, Sies H. Protection against reactive oxygen species by selenoproteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009; 1790:1478–1485. PMID: 19268692.

7. Wang XL, Yang TB, Wei J, Lei GH, Zeng C. Association between serum selenium level and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a non-linear dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr J. 2016; 15:48. PMID: 27142520.

8. Mao S, Zhang A, Huang S. Selenium supplementation and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Endocrine. 2014; 47:758–763. PMID: 24858736.

9. Ogawa-Wong AN, Berry MJ, Seale LA. Selenium and metabolic disorders: an emphasis on type 2 diabetes risk. Nutrients. 2016; 8:80. PMID: 26861388.

10. Houstis N, Rosen ED, Lander ES. Reactive oxygen species have a causal role in multiple forms of insulin resistance. Nature. 2006; 440:944–948. PMID: 16612386.

11. Maritim AC, Sanders RA, Watkins JB 3rd. Diabetes, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: a review. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2003; 17:24–38. PMID: 12616644.

12. Ezaki O. The insulin-like effects of selenate in rat adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 1990; 265:1124–1128. PMID: 2153102.

13. Hei YJ, Farahbakhshian S, Chen X, Battell ML, McNeill JH. Stimulation of MAP kinase and S6 kinase by vanadium and selenium in rat adipocytes. Mol Cell Biochem. 1998; 178:367–375. PMID: 9546621.

14. Furnsinn C, Englisch R, Ebner K, Nowotny P, Vogl C, Waldhausl W. Insulin-like vs. non-insulin-like stimulation of glucose metabolism by vanadium, tungsten, and selenium compounds in rat muscle. Life Sci. 1996; 59:1989–2000. PMID: 8950298.

15. Mueller AS, Pallauf J. Compendium of the antidiabetic effects of supranutritional selenate doses. In vivo and in vitro investigations with type II diabetic db/db mice. J Nutr Biochem. 2006; 17:548–560. PMID: 16443359.

16. McNeill JH, Delgatty HL, Battell ML. Insulinlike effects of sodium selenite in streptozocin-induced diabetic rats. Diabetes. 1991; 40:1675–1678. PMID: 1756907.

17. Becker DJ, Reul B, Ozcelikay AT, Buchet JP, Henquin JC, Brichard SM. Oral selenate improves glucose homeostasis and partly reverses abnormal expression of liver glycolytic and gluconeogenic enzymes in diabetic rats. Diabetologia. 1996; 39:3–11. PMID: 8720597.

18. Kohler LN, Florea A, Kelley CP, Chow S, Hsu P, Batai K, Saboda K, Lance P, Jacobs ET. Higher plasma selenium concentrations are associated with increased odds of prevalent type 2 diabetes. J Nutr. 2018; 148:1333–1340. PMID: 29924331.

19. Li XT, Yu PF, Gao Y, Guo WH, Wang J, Liu X, Gu AH, Ji GX, Dong Q, Wang BS, Cao Y, Zhu BL, Xiao H. Association between plasma metal levels and diabetes risk: a case-control study in China. Biomed Environ Sci. 2017; 30:482–491. PMID: 28756807.

20. Laclaustra M, Navas-Acien A, Stranges S, Ordovas JM, Guallar E. Serum selenium concentrations and diabetes in U.S. adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2004. Environ Health Perspect. 2009; 117:1409–1413. PMID: 19750106.

21. Park K, Rimm EB, Siscovick DS, Spiegelman D, Manson JE, Morris JS, Hu FB, Mozaffarian D. Toenail selenium and incidence of type 2 diabetes in U.S. men and women. Diabetes Care. 2012; 35:1544–1551. PMID: 22619078.

22. Hansen AF, Simic A, Asvold BO, Romundstad PR, Midthjell K, Syversen T, Flaten TP. Trace elements in early phase type 2 diabetes mellitus: a population-based study. The HUNT study in Norway. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2017; 40:46–53. PMID: 28159221.

23. Gao H, Hagg S, Sjogren P, Lambert PC, Ingelsson E, van Dam RM. Serum selenium in relation to measures of glucose metabolism and incidence of type 2 diabetes in an older Swedish population. Diabet Med. 2014; 31:787–793. PMID: 24606531.

24. Yuan Y, Xiao Y, Yu Y, Liu Y, Feng W, Qiu G, Wang H, Liu B, Wang J, Zhou L, Liu K, Xu X, Yang H, Li X, Qi L, Zhang X, He M, Hu FB, Pan A, Wu T. Associations of multiple plasma metals with incident type 2 diabetes in Chinese adults: the Dongfeng-Tongji Cohort. Environ Pollut. 2018; 237:917–925. PMID: 29429611.

25. Galan-Chilet I, Grau-Perez M, De Marco G, Guallar E, Martin-Escudero JC, Dominguez-Lucas A, Gonzalez-Manzano I, Lopez-Izquierdo R, Briongos-Figuero LS, Redon J, Chaves FJ, Tellez-Plaza M. A gene-environment interaction analysis of plasma selenium with prevalent and incident diabetes: The Hortega study. Redox Biol. 2017; 12:798–805. PMID: 28437656.

26. Rostom A, Dube C, Cranney A, Saloojee N, Sy R, Garritty C, Sampson M, Zhang L, Yazdi F, Mamaladze V, Pan I, McNeil J, Moher D, Mack D, Patel D. Celiac disease. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). 2004; 104:1–6.

27. Zhang H, Yan C, Yang Z, Zhang W, Niu Y, Li X, Qin L, Su Q. Alterations of serum trace elements in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2017; 40:91–96. PMID: 28159227.

28. Skalnaya MG, Skalny AV, Yurasov VV, Demidov VA, Grabeklis AR, Radysh IV, Tinkov AA. Serum trace elements and electrolytes are associated with fasting plasma glucose and HbA(1c) in postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2017; 177:25–32. PMID: 27752920.

29. Lu CW, Chang HH, Yang KC, Kuo CS, Lee LT, Huang KC. High serum selenium levels are associated with increased risk for diabetes mellitus independent of central obesity and insulin resistance. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2016; 4:e000253.

30. Alehagen U, Johansson P, Bjornstedt M, Rosen A, Post C, Aaseth J. Relatively high mortality risk in elderly Swedish subjects with low selenium status. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016; 70:91–96. PMID: 26105108.

31. Stranges S, Galletti F, Farinaro E, D'Elia L, Russo O, Iacone R, Capasso C, Carginale V, De Luca V, Della Valle E, Cappuccio FP, Strazzullo P. Associations of selenium status with cardiometabolic risk factors: an 8-year follow-up analysis of the Olivetti Heart study. Atherosclerosis. 2011; 217:274–278. PMID: 21497349.

32. Bleys J, Navas-Acien A, Guallar E. Serum selenium and diabetes in U.S. adults. Diabetes Care. 2007; 30:829–834. PMID: 17392543.

33. Su LQ, Jin YL, Unverzagt FW, Cheng YB, Hake AM, Ran L, Ma F, Liu JY, Chen C, Bian JC, Wu XP, Gao S. Nail selenium level and diabetes in older people in rural China. Biomed Environ Sci. 2016; 29:818–824. PMID: 27998388.

34. Vinceti M, Grioni S, Alber D, Consonni D, Malagoli C, Agnoli C, Malavolti M, Pala V, Krogh V, Sieri S. Toenail selenium and risk of type 2 diabetes: the ORDET cohort study. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2015; 29:145–150. PMID: 25169979.

35. Liu B, Feng W, Wang J, Li Y, Han X, Hu H, Guo H, Zhang X, He M. Association of urinary metals levels with type 2 diabetes risk in coke oven workers. Environ Pollut. 2016; 210:1–8. PMID: 26689646.

36. Feng W, Cui X, Liu B, Liu C, Xiao Y, Lu W, Guo H, He M, Zhang X, Yuan J, Chen W, Wu T. Association of urinary metal profiles with altered glucose levels and diabetes risk: a population-based study in China. PLoS One. 2015; 10:e0123742. PMID: 25874871.

37. Wei J, Zeng C, Gong QY, Yang HB, Li XX, Lei GH, Yang TB. The association between dietary selenium intake and diabetes: a cross-sectional study among middle-aged and older adults. Nutr J. 2015; 14:18. PMID: 25880386.

38. Stranges S, Sieri S, Vinceti M, Grioni S, Guallar E, Laclaustra M, Muti P, Berrino F, Krogh V. A prospective study of dietary selenium intake and risk of type 2 diabetes. BMC Public Health. 2010; 10:564. PMID: 20858268.

39. Stapleton SR. Selenium: an insulin-mimetic. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000; 57:1874–1879. PMID: 11215514.

40. Rasekh HR, Potmis RA, Nonavinakere VK, Early JL, Iszard MB. Effect of selenium on plasma glucose of rats: role of insulin and glucocorticoids. Toxicol Lett. 1991; 58:199–207. PMID: 1949078.

41. Mueller AS, Bosse AC, Most E, Klomann SD, Schneider S, Pallauf J. Regulation of the insulin antagonistic protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B by dietary Se studied in growing rats. J Nutr Biochem. 2009; 20:235–247. PMID: 18602818.

42. Zeng MS, Li X, Liu Y, Zhao H, Zhou JC, Li K, Huang JQ, Sun LH, Tang JY, Xia XJ, Wang KN, Lei XG. A high-selenium diet induces insulin resistance in gestating rats and their offspring. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012; 52:1335–1342. PMID: 22342560.

43. Liu Y, Zhao H, Zhang Q, Tang J, Li K, Xia XJ, Wang KN, Li K, Lei XG. Prolonged dietary selenium deficiency or excess does not globally affect selenoprotein gene expression and/or protein production in various tissues of pigs. J Nutr. 2012; 142:1410–1416. PMID: 22739382.

44. Pinto A, Juniper DT, Sanil M, Morgan L, Clark L, Sies H, Rayman MP, Steinbrenner H. Supranutritional selenium induces alterations in molecular targets related to energy metabolism in skeletal muscle and visceral adipose tissue of pigs. J Inorg Biochem. 2012; 114:47–54. PMID: 22694857.

45. Zhou J, Huang K, Lei XG. Selenium and diabetes: evidence from animal studies. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013; 65:1548–1556. PMID: 23867154.

46. McClung JP, Roneker CA, Mu W, Lisk DJ, Langlais P, Liu F, Lei XG. Development of insulin resistance and obesity in mice overexpressing cellular glutathione peroxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004; 101:8852–8857. PMID: 15184668.

47. Stranges S, Marshall JR, Natarajan R, Donahue RP, Trevisan M, Combs GF, Cappuccio FP, Ceriello A, Reid ME. Effects of long-term selenium supplementation on the incidence of type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007; 147:217–223. PMID: 17620655.

48. Lippman SM, Klein EA, Goodman PJ, Lucia MS, Thompson IM, Ford LG, Parnes HL, Minasian LM, Gaziano JM, Hartline JA, Parsons JK, Bearden JD 3rd, Crawford ED, Goodman GE, Claudio J, Winquist E, Cook ED, Karp DD, Walther P, Lieber MM, Kristal AR, Darke AK, Arnold KB, Ganz PA, Santella RM, Albanes D, Taylor PR, Probstfield JL, Jagpal TJ, Crowley JJ, Meyskens FL Jr, Baker LH, Coltman CA Jr. Effect of selenium and vitamin E on risk of prostate cancer and other cancers: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA. 2009; 301:39–51. PMID: 19066370.

49. Thompson PA, Ashbeck EL, Roe DJ, Fales L, Buckmeier J, Wang F, Bhattacharyya A, Hsu CH, Chow HH, Ahnen DJ, Boland CR, Heigh RI, Fay DE, Hamilton SR, Jacobs ET, Martinez ME, Alberts DS, Lance P. Selenium supplementation for prevention of colorectal adenomas and risk of associated type 2 diabetes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016; 108:djw152. PMID: 27530657.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary materials related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2018.0123.

Supplementary Fig. 1

Sensitivity analysis of the meta-analysis of studies comparing odds ratio (OR) of diabetes mellitus between the high and low selenium groups. CI, confidence interval.

Supplementary Fig. 2

Funnel plot for publication bias in studies comparing odds ratio of diabetes mellitus between the high and low selenium groups.

Supplementary Fig. 3

Meta-regression analysis based on the mean selenium (Se) level for each study.

Fig. 2

Forest plots summarizing the odds ratio (OR) of the association between Se levels and the presence of diabetes mellitus. CI, confidence interval.

Table 1

Summary of the 20 observational studies included in the present meta-analysis

| Study | Location | Design | Study population | No. of subjects | No. of DM (%) | Age, yr, mean or median | Selenium concentration, mean or median | Selenium measurement | Selenium classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yuan et al. (2018) [24] | China | Cross-sectional | Population based | 2,078 | 1,039 (50) | Controls: 62.8 | Controls: 61.7 | Blood, μg/L | Quartile |

| 1:1 match | Cases: 62.9 | Cases: 64.3 | |||||||

| Kohler et al. (2018) [18] | USA | Cross-sectional | Population based | 1,727 | 172 (10) | 63.1 | 139.8 | Blood, μg/L | Tertile |

| Li et al. (2017) [19] | China | Cross-sectional | Population based | 551 | 122 (22.1) | 66.4 | 16.4 | Blood, μg/L | Tertile |

| Galan-Chilet et al. (2017) [25] | Spain | Cross-sectional | Population based | 1,,452 | 120 | 49 | 84.2 | Blood, μg/L | Tertile |

| Hansen et al. (2017) [22] | Norway | Cross-sectional | Population based | 883 | 128 | Controls: 61.4 | Controls: 101.4a | Blood, μg/L | Quartile |

| Cases: 65.2 | Cases: 101.2a | ||||||||

| Zhang et al. (2017) [27] | China | Cross-sectional | Population based | 1,837 | 510 | Controls: 55.2 | Controls: 200 | Blood, μg/L | Quartile |

| Cases: 57.7 | Cases: 210 | ||||||||

| Skalnaya et al. (2017) [28] | Russia | Cross-sectional | Population based | 128 | 64 (50) | Controls: 56.7 | Controls: 110.2 | Blood, μg/L | Median |

| Menopausal women | 1:1 match | Cases: 55.8 | Cases: 126.8 | ||||||

| Lu et al. (2016) [29] | Taiwan | Cross-sectional | Hospital, 40 yr or older | 847 | 303 (35.8) | 63.9 | 86.7a | Blood, μg/L | Quartile |

| 1:2 match | |||||||||

| Alehagen et al. (2016) [30] | Sweden | Cross-sectional | Population based | 668 | 146 | NA | 67.1 | Blood, μg/L | Quartile |

| 70–80 yr | |||||||||

| Gao et al. (2014) [23] | Sweden | Cohort | Population based | 1,539 | 53 (for 10 yr) | 49.7 | 75.6 | Blood, μg/L | Tertile |

| Stranges et al. (2011) [31] | Italy | Cross-sectional | Population based | 445 | 13 | 50.9 | 77.5 | Blood, μg/L | Tertile |

| Laclaustra et al. (2009) [20] | USA | Cross-sectional | Population based | 917 | 121 | 54.2 | 137.1 | Blood, μg/L | Quartile |

| Bleys et al. (2007) [32] | USA | Cross-sectional | Population based | 8,876 | 1,379 | Controls: 42.8 | Controls: 125.7 | Blood, μg/L | Quintile |

| Cases: 58.3 | Cases: 126.5 | ||||||||

| Su et al. (2016) [33] | China | Cross-sectional | Population based | 1,856 | 163 | 74 | 0.461a | Nail, μg/g | Quartile |

| 65 yr or older | |||||||||

| Vinceti et al. (2015) [34] | Italy | Cross-sectional | Population based | 621 | 226 | Controls: 50.9 | 0.57 | Nail, μg/g | Quartile |

| Women, 35–70 yr | Cases: 51.2 | ||||||||

| Park et al. (2012) [21] | USA | Cohort | Population based | Men: 3,535 | 780 | Men: 59.6 | Men: 0.84 | Nail, μg/g | Quintile |

| Nurses, 30–55 yr | Women: 3,630 | Women: 52.6 | Women: 0.77 | ||||||

| Health professional, 40–75 yr | |||||||||

| Liu et al. (2016) [35] | China | Cross-sectional | The coke oven workers | 1,493 | 102 | Controls: 41.8 | Controls: 10 | Urine, μg/L | Tertile |

| Cases: 47 | Cases: 11.5 | ||||||||

| Feng et al. (2015) [36] | China | Cross-sectional | Population based | 2,242 | 218 | 53 | 7.42a | Urine, μg/L | Quartile |

| Wei et al. (2015) [37] | China | Cross-sectional | Population based | 5,423 | 525 | Controls: 52.9 | Controls: 43.2 | Intake, μg/day | Quartile |

| 40 yr or older | Cases: 54.7 | Cases: 46.8 | |||||||

| Stranges et al. (2010) [39] | Italy | Cohort | Population based | 7,182 | 253 | Controls: 47.1 | Controls: 56.8 | Intake, μg/day | Quintile |

| Healthy women, 34–70 yr | Cases: 51.2 | Cases: 60.9 |

Table 2

The OR of the association between Se levels and the presence of DM by cut-off levels of Se of the highest group

| Cut-off value of Se level of highest group | No. of studies | OR (95% CI) | Heterogeneity (I2), % |

|---|---|---|---|

| <100 μg/L | 6 | 1.90 (1.23–2.93) | 74 |

| 100–120 μg/L | 2 | 4.06 (2.67–6.18) | 0 |

| >120 μg/L | 4 | 2.46 (1.48–4.10) | 79 |

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download