Abstract

We investigated associations between breastfeeding duration and number of children breastfed and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and glycemic control among parous women. We performed a cross-sectional analysis of data for 9,960 parous women from the Korea National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (2010 to 2013). Having ever breastfed was inversely associated with prevalent T2DM (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 0.60; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.42 to 0.87). All ranges of total and average breastfeeding duration showed inverse associations with T2DM. Even short periods of breastfeeding were inversely associated with T2DM (adjusted OR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.38 to 0.99 for a total breastfeeding duration ≤12 months; adjusted OR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.42 to 0.99 for an average breastfeeding duration per child ≤6 months). A longer duration of breastfeeding was associated with better glycemic control in parous women with T2DM (P trend=0.004 for total breastfeeding duration; P trend <0.001 for average breastfeeding duration per child). Breastfeeding may be associated with a lower risk of T2DM and good glycemic control in parous women with T2DM. Breastfeeding may be a feasible method to prevent T2DM and improve glycemic control.

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has increased dramatically worldwide including South Korea [12]. T2DM can result in increased morbidity and mortality and confer a significant economic burden [3]. The potential benefits of breastfeeding, which is a simple and accessible feeding method available to women, for preventing T2DM remain poorly understood.

Breastfeeding has been correlated with maternal cardiovascular health [456]. Lactation may increase insulin sensitivity and improve glucose tolerance [5]. Furthermore, a limited number of epidemiologic studies have proposed that breastfeeding lowers the maternal risk of T2DM [7891011]. However, the evidence for this association is inconsistent, and the strength of this association has differed by grouping of subjects and duration of breastfeeding. Most of the studies have been conducted in developed nations. Moreover, no study has evaluated the association between breastfeeding and glycemic control in parous women with T2DM.

Therefore, we examined the associations of breastfeeding duration and number of children breastfed with prevalent T2DM and glycemic control among parous women with T2DM based on nationally representative data from the South Korean population.

This population-based, cross-sectional study analyzed data from the Korea National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (KNHANES) from 2010 to 2013. Of the 25,712 individuals who participated in the 2010 to 2013 KNHANES, we excluded 11,121 male individuals, 1,806 individuals aged <30 years, 1,750 individuals who were nulliparous, 1,048 individuals who had any missing data, and 27 individuals who were diagnosed with diabetes by a physician before their first delivery. Finally, data from 9,960 parous women were analyzed. All survey participants signed written informed consent forms. The Institutional Review Board of the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reviewed and approved the survey protocol (2010-02CON-21-C, 2011-02CON-06-C, 2012-01EXP-01-2C, 2013-07CON-03-4C).

Subjects were asked about their breastfeeding history, total duration of breastfeeding, and the number of children breastfed. The average breastfeeding duration per child was calculated by dividing the total breastfeeding duration by the number of children breastfed. Subjects were divided into five groups based on the total breastfeeding duration (none, 1 to 12, 13 to 24, 25 to 36, and >36 months) and average breastfeeding duration per child (none, 1 to 6, 7 to 12, 13 to 18, and >18 months).

Information of educational level and monthly household income level was assessed through self-reported questionnaire. We divided subjects into never-smokers and ever-smokers. Subjects who had at least one alcoholic drink per month during during the year before the survey were defined as alcohol drinkers. Subjects were defined as regular exercisers if they performed moderate exercise >5 times/week for >30 minutes per session or vigorous exercise >3 times/week for >20 minutes per session [12]. Trained dieticians assessed the nutritional status of the subjects including daily total calorie intake using a 24-hour dietary recall questionnaire. Subjects also answered questions regarding other reproductive characteristics. Height and weight, and waist circumference (WC) were measured, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure (BP) ≥140 mm Hg, diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg, or treatment with antihypertensive medications. Serum levels of fasting plasma glucose (FPG), total cholesterol, triglyceride, and high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) were measured and low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) was calculated.

T2DM was defined as a FPG level ≥126 mg/dL, current treatment with hypoglycemic agents, or a diagnosis by a physician. In subjects with T2DM (n=1,011), glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level was measured and good glycemic control was defined as a HbA1c level ≤6.5% (48 mmol/mol) [13].

Statistical analyses were conducted using the SAS survey procedure version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). An independent t-test or a Rao-Scott chi-square test was performed to compare the subjects' characteristics. We estimated odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to evaluate the association of breastfeeding duration and number of children breastfed with prevalent T2DM using multivariable logistic regression models. Model 1 was adjusted for age and model 2 was further adjusted for BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, educational level, monthly household income level, daily total energy intake, ever-use of oral contraceptives, and age at first delivery. In model 3, a further adjustment for hypertension and menopausal status was performed. ORs for good glycemic control in subjects with T2DM in relation to breastfeeding duration were also calculated. A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The mean age and mean levels of BMI, WC, and systolic BP and rate of hypertension were higher, while the mean HDL-C and LDL-C levels were lower in women with T2DM (n=1,011) than in women without T2DM (n=8,949). The mean total and average breastfeeding duration were longer in women with T2DM than in women without T2DM.

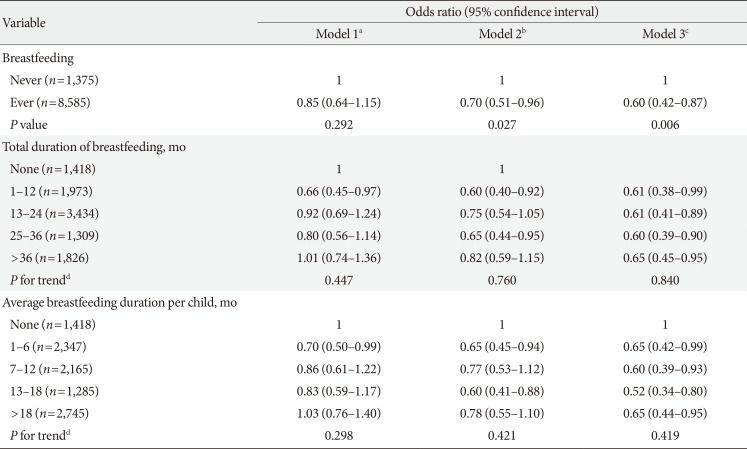

Table 1 provides adjusted ORs (95% CIs) of prevalent T2DM in relation to ever having breastfed and total and average breastfeeding duration. Having ever breastfed was inversely associated with prevalent T2DM after adjusting for potential confounders (OR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.64 to 1.15 in age-adjusted model; OR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.51 to 0.96 in model 2; and OR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.42 to 0.87 in model 3). Compared with women who had never breastfed, all ranges of total breastfeeding duration and average breastfeeding duration per child were significantly inversely associated with T2DM. Although there was no dose-response relationship between breastfeeding duration and T2DM, even women with short breastfeeding duration were also significantly inversely associated with T2DM. In addition, compared with women who had never breastfed, women who had breastfed 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, or ≥7 children had lower odds of T2DM, and the ORs tended to decrease as the number of children breastfed increased (P for trend=0.018).

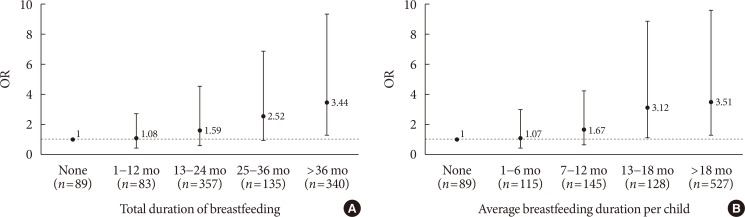

In Fig. 1, compared to women with T2DM who had never breastfed, women who had breastfed for >36 months in their lifetime had an OR of 3.44 (95% CI, 2.18 to 5.93) for good glycemic control. Longer total breastfeeding durations showed increasing ORs (P for trend=0.004). Women with T2DM who had breastfed for ≥13 months per child had good glycemic control, when compared to women with T2DM who had never breastfed. The ORs for good glycemic control also tended to decrease as the average breastfeeding duration per child increased (P for trend <0.001).

Our findings suggest that never having breastfed may be a risk factor for T2DM, and any range of breastfeeding duration and having breastfed a greater number of infants may be beneficial for preventing T2DM. Furthermore, a longer duration of breastfeeding may be helpful for glycemic control in parous women with T2DM, particularly a total breastfeeding duration >36 months or average breastfeeding duration per child ≥13 months.

Consistently, a few cohort studies have supported an inverse association between breastfeeding and maternal T2DM risk. Meta-analyses of these observational studies concluded that there is an inverse association between breastfeeding and maternal T2DM risk and that the risk reduction was greater as breastfeeding duration increased [1415].

Breastfeeding women are burdened with higher energy requirements for milk production, and therefore, breastfeeding can lower postpartum weight retention [16]. Mothers who breastfeed for a shorter duration of time may not lose their visceral fat that is acquired during pregnancy [17]. Meanwhile, excessive weight gain during pregnancy and high pregnancy BMI may be associated with never-breastfeeding or early termination of breastfeeding [18]. As for other possible mechanisms independent of weight or BMI, breastfeeding improves glucose metabolism [19]. Several studies have also reported that breastfeeding is associated with improved metabolic profiles [20].

Interestingly, associations of breastfeeding with good glycemic control were observed in our study. These findings support the previous findings regarding beneficial effects of breastfeeding on metabolic profiles in women with gestational diabetes mellitus [19]. They also highlight the beneficial effects of breastfeeding in parous women with T2DM and suggest that breastfeeding is an additional strategy for glycemic control for this group.

Although women with T2DM or breastfeeding were older and had unfavorable cardiometabolic parameters, women with older age may have more chance to parity and breastfeeding. After adjusting for age, we found reversed favorable associations of breastfeeding with T2DM prevalence and glycemic control different from results of crude analysis, indicating that age may be a critical confounder in these associations. Prospective long-term follow-up studies are needed to clarify the association between breastfeeding and glycemic control in women with T2DM.

The present study has some limitations. The cross-sectional design of this study did not allow us to determine a causal relationship. Second, maternal recall of breastfeeding may be biased over time, and types of breastfeeding were not investigated in the KNHANES. Third, BMI at age of delivery or pregnancy complications could not be considered because of the lack of data collected by the survey. Fourth, diagnosis of T2DM may impact current behaviors.

In conclusion, our study found that breastfeeding was inversely associated with T2DM in Korean parous women and it was also associated with good glycemic control in parous women with T2DM, independent of potential confounding factors. Breastfeeding may be considered a feasible method to prevent T2DM and to improve glycemic control in women with T2DM.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors appreciate Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for providing the data. We are grateful to Dr. Quaker E. Harmon for critical review of this manuscript. No official support or endorsement by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences is intended or should be inferred in this article.

References

1. Whiting DR, Guariguata L, Weil C, Shaw J. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2011 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011; 94:311–321. PMID: 22079683.

2. Task Force Team for Basic Statistical Study of Korean Diabetes Mellitus of Korean Diabetes Association. Park IeB, Kim J, Kim DJ, Chung CH, Oh JY, Park SW, Lee J, Choi KM, Min KW, Park JH, Son HS, Ahn CW, Kim H, Lee S, Lee IB, Choi I, Baik SH. Diabetes epidemics in Korea: reappraise nationwide survey of diabetes “diabetes in Korea 2007”. Diabetes Metab J. 2013; 37:233–239. PMID: 23991400.

3. Gregg EW, Li Y, Wang J, Burrows NR, Ali MK, Rolka D, Williams DE, Geiss L. Changes in diabetes-related complications in the United States, 1990-2010. N Engl J Med. 2014; 370:1514–1523. PMID: 24738668.

4. Stuebe AM, Schwarz EB, Grewen K, Rich-Edwards JW, Michels KB, Foster EM, Curhan G, Forman J. Duration of lactation and incidence of maternal hypertension: a longitudinal cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2011; 174:1147–1158. PMID: 21997568.

5. Schwarz EB, Ray RM, Stuebe AM, Allison MA, Ness RB, Freiberg MS, Cauley JA. Duration of lactation and risk factors for maternal cardiovascular disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 113:974–982. PMID: 19384111.

6. Gunderson EP, Lewis CE, Wei GS, Whitmer RA, Quesenberry CP, Sidney S. Lactation and changes in maternal metabolic risk factors. Obstet Gynecol. 2007; 109:729–738. PMID: 17329527.

7. Ziegler AG, Wallner M, Kaiser I, Rossbauer M, Harsunen MH, Lachmann L, Maier J, Winkler C, Hummel S. Long-term protective effect of lactation on the development of type 2 diabetes in women with recent gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes. 2012; 61:3167–3171. PMID: 23069624.

8. Liu B, Jorm L, Banks E. Parity, breastfeeding, and the subsequent risk of maternal type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010; 33:1239–1241. PMID: 20332359.

9. Schwarz EB, Brown JS, Creasman JM, Stuebe A, McClure CK, Van Den Eeden SK, Thom D. Lactation and maternal risk of type 2 diabetes: a population-based study. Am J Med. 2010; 123:863.e1–863.e6.

10. Villegas R, Gao YT, Yang G, Li HL, Elasy T, Zheng W, Shu XO. Duration of breast-feeding and the incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Diabetologia. 2008; 51:258–266. PMID: 18040660.

11. Stuebe AM, Rich-Edwards JW, Willett WC, Manson JE, Michels KB. Duration of lactation and incidence of type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2005; 294:2601–2610. PMID: 16304074.

12. Oh JY, Yang YJ, Kim BS, Kang JH. Validity and reliability of Korean version of International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) short form. J Korean Acad Fam Med. 2007; 28:532–541.

13. American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2014; 37(Suppl 1):S81–S90. PMID: 24357215.

14. Jager S, Jacobs S, Kroger J, Fritsche A, Schienkiewitz A, Rubin D, Boeing H, Schulze MB. Breast-feeding and maternal risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective study and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2014; 57:1355–1365. PMID: 24789344.

15. Aune D, Norat T, Romundstad P, Vatten LJ. Breastfeeding and the maternal risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014; 24:107–115. PMID: 24439841.

16. Butte NF, King JC. Energy requirements during pregnancy and lactation. Public Health Nutr. 2005; 8:1010–1027. PMID: 16277817.

17. Kinoshita T, Itoh M. Longitudinal variance of fat mass deposition during pregnancy evaluated by ultrasonography: the ratio of visceral fat to subcutaneous fat in the abdomen. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2006; 61:115–118. PMID: 16272815.

18. Baker JL, Michaelsen KF, Sorensen TI, Rasmussen KM. High prepregnant body mass index is associated with early termination of full and any breastfeeding in Danish women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007; 86:404–411. PMID: 17684212.

19. Kjos SL, Henry O, Lee RM, Buchanan TA, Mishell DR Jr. The effect of lactation on glucose and lipid metabolism in women with recent gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol. 1993; 82:451–455. PMID: 8355952.

20. Gunderson EP, Kim C, Quesenberry CP Jr, Marcovina S, Walton D, Azevedo RA, Fox G, Elmasian C, Young S, Salvador N, Lum M, Crites Y, Lo JC, Ning X, Dewey KG. Lactation intensity and fasting plasma lipids, lipoproteins, non-esterified free fatty acids, leptin and adiponectin in postpartum women with recent gestational diabetes mellitus: the SWIFT cohort. Metabolism. 2014; 63:941–950. PMID: 24931281.

Fig. 1

Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of good glycemic control among parous women with type 2 diabetes mellitus (A: P for trend=0.004 for total breastfeeding duration; B: P for trend <0.001 for average breastfeeding duration per child).

Table 1

Multivariable logistic regression analysis for type 2 diabetes mellitus in relation to breastfeeding and breastfeeding duration

aModel 1 was adjusted for age, bModel 2 was adjusted for variables in model 1 plus body mass index, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, educational level, household income level, daily total energy intake, use of oral contraceptives, and age at first delivery, cModel 3 was adjusted for variables in model 2 plus hypertension and menopausal status, dP for trend was obtained using the general linear model.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download