This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Early recognition and appropriate management of diabetic peripheral polyneuropathy (DPNP) is important. We evaluated the necessity of simple, non-invasive tests for DPNP detection in clinical practice. We enrolled 136 randomly-chosen patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and examined them with the 10-g Semmes-Weinstein monofilament examination, the 128-Hz tuning-fork, ankle-reflex, and pinprick tests; the Total Symptom Score and the 15-item self-administered questionnaire of the Michigan Neuropathy Screening Instrument. Among 136 patients, 48 had subjective neuropathic symptoms and 88 did not. The abnormal-response rates varied depending on the methods used according to the presence of subjective neuropathic symptoms (18.8% vs. 5.7%, P<0.05; 58.3% vs. 28.4%, P<0.005; 81.3% vs. 54.5%, P<0.005; 12.5% vs. 5.7%, P=0.195; 41.7% vs. 2.3%, P<0.001; and 77.1% vs. 9.1%, P<0.001; respectively). The largest abnormal response was derived by combining all methods. Moreover, these tests should be implemented more extensively in diabetic patients without neuropathic symptoms to detect DPNP early.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, Diabetic neuropathies, Diagnosis, Neurologic examination, Surveys and questionnaires

INTRODUCTION

Diabetic peripheral polyneuropathy (DPNP) is the most common microvascular complication and an amputation risk factor in patients with diabetes [

12]. Therefore, early recognition and appropriate management of DPNP are important.

Unfortunately, methods for DPNP detection are underutilized in primary-care practice and DPNP is underdiagnosed [

34]. To confirm the diagnosis, a nerve-conduction study or skin biopsy is required [

56]. However, these procedures are invasive and may be unsuitable for use in clinical practice [

7]. The identification of potential patients with DPNP, particularly by non-specialists, requires easily applicable and clinically reliable screening and diagnostic methods. Various diagnostic methods have so far been developed and used [

89]. In this study, we evaluated the diagnostic correlation of simple and non-invasive methods appropriate for DPNP detection in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) according to the presence of neuropathic symptoms to reconfirm the necessity of these tests in clinical practice.

METHODS

Study population

We enrolled 162 patients with T2DM who were randomly chosen. The subjects were examined with all screening tests including the 10-g Semmes-Weinstein monofilament examination (SWME), the 128-Hz tuning-fork, ankle-reflex, and pinprick tests; the Total Symptom Score (TSS), and the 15-item self-administered questionnaire of the Michigan Neuropathy Screening Instrument (MNSI questionnaire) between January 2013 and December 2013 at one tertiary hospital. Examinations except for the TSS and MNSI questionnaire were performed by one examiner who did not recognize the presence of symptoms. We excluded 26 patients with chronic alcohol abuse, end stage terminal disease (chronic kidney disease, hepatic dysfunction, or cancer), vitamin deficiency (B1, B6, B12, E, or folic acid), or who were receiving neurotoxic medications [

10]. Subjective neuropathic symptoms were defined as symmetrical burning pain, electrical sensation, stabbing sensation, paresthesia, or deep aching pain in the lower limbs having started at the toes. All included subjects were aged ≥40 years.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Hanyang University Hospital in Seoul, Korea (No. HYUH 2014-05-002).

Tests for diabetic peripheral polyneuropathy

The SWME was performed at 10 touch sites (one dorsal and nine plantar sites) per foot. The monofilament was applied perpendicular to the foot and touched the skin until it bended by approximately 1 cm. The total duration of the approach, skin contact, and monofilament removal should be approximately 2 seconds. A total score ≤8/10 was considered abnormal [

11].

The 128-Hz tuning-fork test was bilaterally applied to the bony prominence situated at the dorsum of the first toe proximal to the nail bed. The patient was asked to report the time when vibration diminished below perception. The tuning-fork was also applied to the dorsal aspect of the distal phalanx of the examiner's thumb [

12]. A detection-time difference between the patient and the examiner ≥10 seconds was considered abnormal.

The ankle-reflex test was performed at both ankles. While the patient was kneeling, the examiner dorsiflexed the foot and gently stroked the Achilles tendon with the reflex hammer [

11]. An absent or decreased ankle reflex was considered abnormal.

The pinprick test was performed over the plantar aspect of the distal first, third, and fifth toes of each foot with the stimulus applied once per site [

11]. An absent or dull sensation was considered abnormal.

The MNSI questionnaire was self-administered. ‘Yes’ responses to questions 1–3, 5–6, 8–9, 11–12, 14–15 and ‘No’ responses to questions 7 and 13 were each counted as one point. Questions 4 and 10 are not included in the published scoring algorithm [

13]. A total score ≥3 was considered abnormal.

The TSS was self-administered. The patient was asked to assess the intensity (absent, mild, moderate, or severe) and the frequency (occasional, frequent, or continuous) of four symptoms (pain, burning, paresthesia, and numbness) [

14]. A total score ≥4 was considered abnormal.

Statistical analyses

Data analyses were performed using SPSS version 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). An independent t-test was used for continuous data and the chi-square and Fisher's exact tests for categorical data. A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

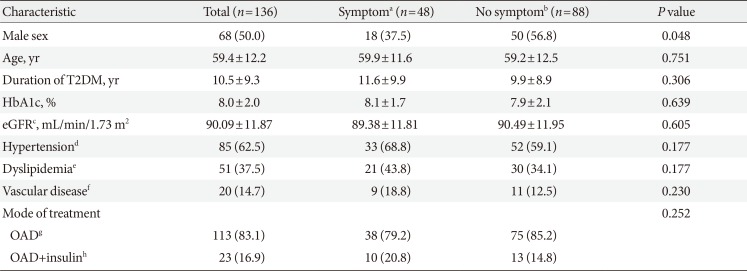

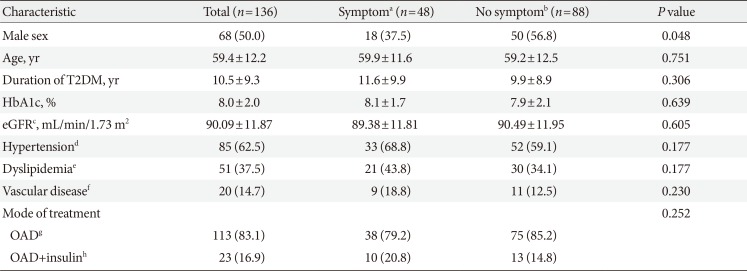

The baseline characteristics of the 136 patients are described in

Table 1. Forty-eight patients (35.3%) had subjective neuropathic symptoms. There was a significant difference in sex but not in age, duration of T2DM, glycosylated hemoglobin, prevalence of hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetic macrovascular complications, glomerular filtration rate, and mode of treatment between the patients with and without subjective neuropathic symptoms.

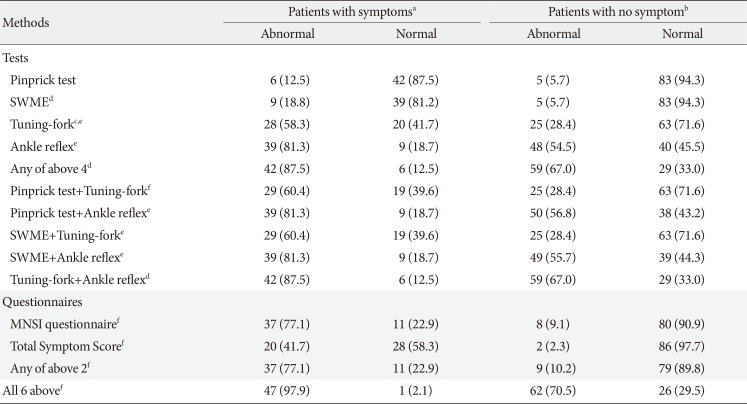

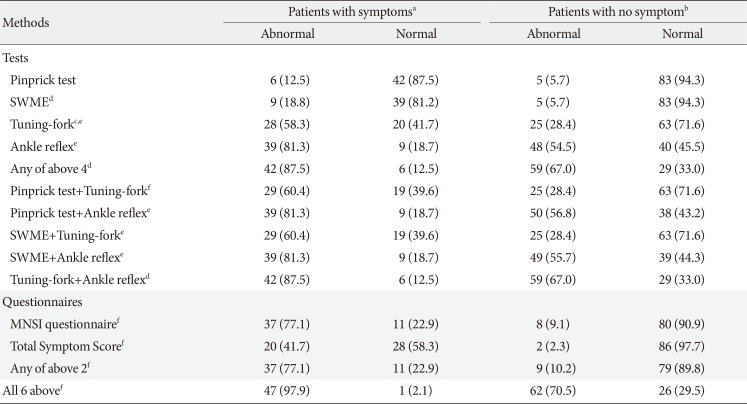

The results of all six methods for the detection of DPNP are described in

Table 2. The abnormal response rates varied depending on the methods used. The abnormal responses in the pinprick, 128-Hz tuning-fork, and ankle-reflex tests in patients with subjective neuropathic symptoms were similar to those in patients without neuropathic symptoms (6 [54.5%] vs. 5 [45.5%]; 28 [52.8%] vs. 25 [47.2%]; 39 [44.8%] vs. 48 [55.2%]). However, the abnormal responses in the SWME in patients with subjective neuropathic symptoms were larger than those in patients without neuropathic symptoms (9 [64.3%] vs. 5 [35.7%]). The result derived from a combination of the pinprick, SWME, 128-Hz tuning-fork, and ankle-reflex tests was the same as that derived from a combination of the 128-Hz tuning-fork and ankle-reflex tests. Abnormal responses in the MNSI questionnaire and TSS in patients with subjective neuropathic symptoms were larger than in patients without neuropathic symptoms. The result derived from the combination of the MNSI questionnaire and TSS was similar to that of the MNSI questionnaire. The largest abnormal response was derived from the combination of all methods.

DISCUSSION

This study showed that a combination of simple and non-invasive methods would be better than using just one test for detecting DPNP in clinical practice in diabetic groups irrespective of subjective neuropathic symptoms. The MNSI questionnaire could be useful for the detection of DPNP in patients with subjective neuropathic symptoms.

Instruments such as the SWME, ankle-reflex, and 128-Hz tuning-fork tests have been recommended as screening tools for DPNP [

9]. They can be used alone or combined to assess and contribute to the clinical diagnosis of DPNP. It was reported that the combination of these tests had greater than 87% sensitivity for DPNP detection [

15]. In this study, we found that combining at least the 128-Hz tuning-fork and ankle-reflex tests would be needed for the detection of DPNP.

We observed that the MNSI questionnaire could be a useful tool for detecting DPNP in patients with neuropathic symptoms. The MNSI includes a 15-item self-administered questionnaire and a lower-extremity examination [

13]. When used separately, the MNSI questionnaire and the examination performed similarly in predicting confirmed clinical neuropathy [

16]. However, among patients with DPNP, up to 50% may be asymptomatic [

9]. Therefore, a combination of various tests would be required for the detection of DPNP in patients with T2DM.

This study has several limitations. First, all tests except for the TSS and MNSI questionnaire were performed by one examiner who did not recognize whether the subjects had neuropathic symptoms. However, the results would vary depending on the level of the examiner's proficiency. Second, the diagnosis of DPNP would have been more certain if we had performed nerve-conduction studies and skin biopsies.

In conclusion, our findings indicate that in diabetic patients with and without neuropathic symptoms, examination with as many tests and questionnaires as possible is important for early DPNP detection.

Table 1

Baseline characteristics of the patients enrolled in the study and according to the presence of subjective neuropathic symptoms

|

Characteristic |

Total (n=136) |

Symptoma (n=48) |

No symptomb (n=88) |

P value |

|

Male sex |

68 (50.0) |

18 (37.5) |

50 (56.8) |

0.048 |

|

Age, yr |

59.4±12.2 |

59.9±11.6 |

59.2±12.5 |

0.751 |

|

Duration of T2DM, yr |

10.5±9.3 |

11.6±9.9 |

9.9±8.9 |

0.306 |

|

HbA1c, % |

8.0±2.0 |

8.1±1.7 |

7.9±2.1 |

0.639 |

|

eGFRc, mL/min/1.73 m2

|

90.09±11.87 |

89.38±11.81 |

90.49±11.95 |

0.605 |

|

Hypertensiond

|

85 (62.5) |

33 (68.8) |

52 (59.1) |

0.177 |

|

Dyslipidemiae

|

51 (37.5) |

21 (43.8) |

30 (34.1) |

0.177 |

|

Vascular diseasef

|

20 (14.7) |

9 (18.8) |

11 (12.5) |

0.230 |

|

Mode of treatment |

|

|

|

0.252 |

|

OADg

|

113 (83.1) |

38 (79.2) |

75 (85.2) |

|

OAD+insulinh

|

23 (16.9) |

10 (20.8) |

13 (14.8) |

Table 2

Results of all methods according to the presence of subjective neuropathic symptoms

|

Methods |

Patients with symptomsa

|

Patients with no symptomb

|

|

Abnormal |

Normal |

Abnormal |

Normal |

|

Tests |

|

|

|

|

|

Pinprick test |

6 (12.5) |

42 (87.5) |

5 (5.7) |

83 (94.3) |

|

SWMEd

|

9 (18.8) |

39 (81.2) |

5 (5.7) |

83 (94.3) |

|

Tuning-forkc,e

|

28 (58.3) |

20 (41.7) |

25 (28.4) |

63 (71.6) |

|

Ankle reflexe

|

39 (81.3) |

9 (18.7) |

48 (54.5) |

40 (45.5) |

|

Any of above 4d

|

42 (87.5) |

6 (12.5) |

59 (67.0) |

29 (33.0) |

|

Pinprick test+Tuning-forkf

|

29 (60.4) |

19 (39.6) |

25 (28.4) |

63 (71.6) |

|

Pinprick test+Ankle reflexe

|

39 (81.3) |

9 (18.7) |

50 (56.8) |

38 (43.2) |

|

SWME+Tuning-forke

|

29 (60.4) |

19 (39.6) |

25 (28.4) |

63 (71.6) |

|

SWME+Ankle reflexe

|

39 (81.3) |

9 (18.7) |

49 (55.7) |

39 (44.3) |

|

Tuning-fork+Ankle reflexd

|

42 (87.5) |

6 (12.5) |

59 (67.0) |

29 (33.0) |

|

Questionnaires |

|

|

|

|

|

MNSI questionnairef

|

37 (77.1) |

11 (22.9) |

8 (9.1) |

80 (90.9) |

|

Total Symptom Scoref

|

20 (41.7) |

28 (58.3) |

2 (2.3) |

86 (97.7) |

|

Any of above 2f

|

37 (77.1) |

11 (22.9) |

9 (10.2) |

79 (89.8) |

|

All 6 abovef

|

47 (97.9) |

1 (2.1) |

62 (70.5) |

26 (29.5) |

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download