Journal List > J Korean Acad Nurs > v.49(6) > 1142079

The role of registered nurses is expanding in scope as the healthcare paradigm shifts from acute, hospital-based care to community and population-based care. Given this paradigm shift, this study explores the legal aspects of the role of a registered nurse.

We used document analysis for extracting laws and legal orders related to nursing from the entirety of Korean law. Using textualism approach, we examined the contents utilizing a framework that was developed based on the role classification of community nurses by Clark in this study.

A total of 119 items related to nursing were derived from 64 laws. Of these, 71.4 % can be performed by people in multiple types of occupations including nurses. As a result of analyzing required qualifications, 45.4% of 119 items required additional qualifications besides registered nurse license. Analysis of workplace and activity type demonstrated that 26.1% of the 119 items were related to medical institutions, with nurses performing mostly “Client-oriented role.” More than half (68.9%) were non-medical institutions, with nurses performing mostly “Delivery-oriented role.” Some, however, did not stipulate the nurse's roles clearly.

Therefore, to match the enhanced scope and responsibilities of registered nurses and to appropriately recognize, guide, and hold these nurses accountable, laws and policy must reflect these changes. In doing so, these updated laws and policies will ultimately serve as a basis for improving the quality and safety of nursing services.

Laws are enacted to govern behavior and to help implement public policy [1]. For this reason, laws affect people's rights and obligations in various domains of life at the individual level, while influencing safety, order, and welfare at the national level. In this context, laws related to public health play a key role in protecting the health and safety of the public, and maximizing public welfare [2]. Therefore, society grants exclusive rights to the healthcare workforce to conduct its work-specific activities. This ensures that public interest—and more specifically, the health of the people—is protected [3]. These exclusive rights are generally specified in a country's law [45]. Thus, the rights of a person to perform certain activities are protected within that country. Accordingly, many interest groups actively intervene in the legislative process to ensure their expertise is recognized and their right to practice is protected [6].

Nurses, who constitute the bulk of the healthcare workforce, play key roles not only in medical institutions but also in the overall community due to increasing demand for nursing services with the aging population, and the presence of chronic diseases [789]. In addition, nurses influence the political process—in particular, legislation and policymaking—to improve the legal system as it relates to nursing [10]. Since 1985, the International Council of Nurses (ICN) has argued that government regulations on nursing are required to provide qualitatively guaranteed public health services [11]. Countries including the U.S., Japan, Germany, Canada, and Taiwan have already established individual laws related to nursing [12]. These laws generally provide the definition of nursing personnel, the scope of a nurse's practice, and the educational or certification requirements necessary to qualify as a nurse [13]. Nursing laws can provide high-quality nursing services, while enabling the recent paradigm shifts in the public-centered health care system and enhancing the expertise of nursing services [13].

The healthcare paradigm in Korea is shifting from disease treatment and medical institutions to disease prevention and community. As this change takes place, the role of nurses will gradually expand within Korean communities. However, the Korean legal system is slow in developing laws and policies aimed at accepting these nursing-related changes. Because the Korean healthcare system has primarily focused on disease treatment [14], policy makers have been less interested in developing nursing policy [15].

In this study, we thoroughly examined Korean laws to analyze registered nurses' roles, the extent of activities, and the scope of practice of registered nurses. In addition, we proposed areas for potential improvement by identifying legal imperfections related to nursing in Korea.

This study was conducted by examining laws and legal orders specifying the roles of registered nurses in the current Korean workforce. Thus, we used a “document analysis” for reviewing or analyzing documents, which is suitable for repeated reviews [16]. Document analysis includes skimming, reading, and interpretation [16]; we used textualism based on their linguistic meaning [17] in the interpretation process. There are numerous methods of interpreting laws, such as textualism, intentionalism, and purposivism [18]. Among these, textualism has the advantage of securing the legitimacy of the law by emphasizing the interpretation's faithfulness to the original meaning [19]. Thus, we chose textualism to focus thoroughly on the meaning of the law itself because the purpose of this study was to compare and analyze the law—in its entirety—as it relates to the scope of nursing practice in Korea.

The legislative system of Korea has been systematized by the Constitution, the law created by the National Assembly for implementing constitutional principles, and administrative legislation created by administrative power for the effective enforcement of laws. Administrative legislation is divided into legal orders that are binding and administrative rules that are non-binding. The objects of this study were the laws and legal orders (enforcement decrees and rules) that were being implemented at the time of January 14, 2018. We excluded laws and legal orders that were enacted or amended before January 14, 2018 but yet to take effect at that time. We searched for the terms “nurse,” “nursing,” and “medical personnel” on the National Law Information Center website (http://www.law.go.kr/main.html), which is operated by the Ministry of Government Legislation.

The practice scope of registered nurses can be divided according

to workplace and practice role. This study mainly analyzed “Where the nurses could work” and “What kind of work they could do.” To begin, we carefully analyzed the extracted contents from the laws and legal orders regarding work qualifications, workplace, and government department in charge of the work. Subsequently, based on the workplace classifications, we analyzed the type of practice among registered nurses using the following developed framework.

The role of nurses in the community is becoming important, as the role of nurses in primary care is being emphasized globally in economic and demographic terms [7]. The World Health Organization (WHO) designated the year 2020 as the “Year of the Nurse” to acknowledge and encourage the fact that nurses play a key role in the realization of universal health coverage (UHC), and the international community is also actively joining in this trend [20]. In 2002, the ICN defined “nursing subjects” as “individuals of all ages regardless of whether they were ill or not,” and “nursing roles” as “advocacy, promotion of a safe environment, research, participation in shaping health policy, and so on, in addition to caring for those who are ill.” [21] This definition aimed to reflect upon and include the broad scope of roles performed by nurses [22]. Therefore, our study focused not only on nurses in medical institutions but also on nurses who are primary health care providers who play an important role in the community. We also aimed to develop a framework that could incorporate all laws related to nursing in Korea in addition to the Medical Service Act, which regulates the nursing practice in medical institutions.

According to Clark [23], nursing activities regarding health promotion and disease prevention outside of hospitals are “community health nursing,” and the scope of services include everything from health promotion to illness care. This classification developed by Clark [23] covers a wide range of areas, from health promotion and disease prevention to medical treatment. Therefore, because the role classification of community nurses proposed by Clark is adaptable to nurses' roles in both hospitals and the community, our research team developed a new analysis framework (Table 1) [23]. This framework was restructured to appropriately cover the contents of the Korean laws. We first matched the nursing activities prescribed in Korean laws to Clark's classification and deleted some roles such as “Role model,” “Case manager,” “Change agent,” “Social marketer,” “Coalition builder,” and “Liaison,” because these were not classified contents or were similar to definitions of other roles. We also integrated “Educator” and “Counselor” under “Client-oriented role” because health education and counseling are closely intertwined [24]. “Educator & counselor” was added to the “Population-oriented role” in order to classify roles by their subjects. In addition, “Caregiver” was subdivided into levels I, II, and III according to degree of involvement in medical treatment. “Advocator” in “Client-oriented role” and “Leader” in “Delivery-oriented role” were developed to fully reflect the contents of the law in Korea. Our research team moved “Advocator” from “Population-oriented role” to “Client-oriented role” and interpreted the type of “Advocator” broadly to reflect the original meaning of “advocate” as encompassing all acts to protect and support the subjects [2526]. “Leader” was moved from “Population-oriented role” to “Delivery-oriented role” and integrated with “Coordinator.” We also gave a wide range of new meanings to each type, as supervisor or director, to cover the definitions.

The classification framework developed in this study incorporates all areas of nurse duties within both medical institutions, as prescribed by Article 3 of the Medical Service Act, and the community. Moreover, the framework is adaptable to Korea's particular circumstances, in which the role of nurses has recently expanded into the community.

To avoid omission of nursing-related content in the laws and legal orders, thereby improving the accuracy of the study, each law from which we extracted content was reviewed four times. Additionally, two researchers categorized and analyzed the content of registered nurses' tasks according to the framework independently. If discrepancies were found between the two researchers, they agreed on a consensus. If no consensus was found, the issue was analyzed by a third researcher. These measures were taken to enhance the credibility of the study.

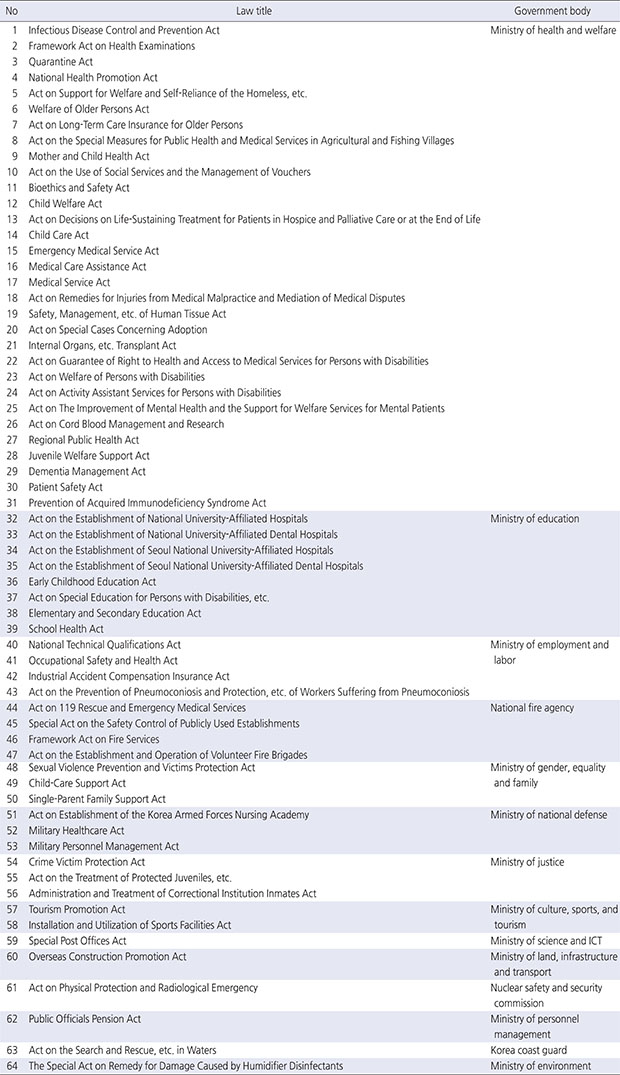

As a result of searching the keywords “nursing,” “nurse,” and “medical personnel,” 105, 132, and 107 provisions were extracted, respectively. Of these, 220 were included in the study after excluding 21 duplicates extracted during the keyword search, as well as 103 provisions that were not related to the scope of the registered nurses. The 220 provisions were merged according to their content. It was considered as a single item if the law and the legal orders of the law, or two different laws stipulated the same content. Finally, 119 items related to the scope of registered nurses' practice were extracted from 64 laws (Appendix) and selected for the final analysis (Figure 1). We coded these 119 items by document analysis and the textualism approach.

First, we analyzed which personnel were authorized to perform the 119 items. Registered nurses can perform all 119 items. However, only 34 of the items can be performed by registered nurses, while the other 85 can also be performed by people in multiple types of occupations such as doctors, pharmacists, paramedics, nurse assistants, nutritionists, and social workers (Table 2).

Next, we analyzed the qualifications required for registered nurses to perform the 119 items. Fifty-four of 119 items require additional qualifications as well as a registered nurse license. Twenty-eight of the 54 items demand a certain length of relevant experience, and 10 require other certification qualifications, such as being a specialized nurse or firefighting officer, whilst some required both.

As a result of analyzing which ministry manages the 119 items, 72 were found to be managed by the Ministry of Health and Welfare. The remaining were managed by the Ministry of Employment and Labor, the Ministry of Education, the National fire agency, and other organizations.

We then categorized the 119 items by workplace. Thirty-one items were performed in medical institutions such as general hospitals, rehabilitation hospitals, military health and medical services institutions, organ transplant hospitals, medical institutions producing embryos, emergency radiological and medical centers, and infection control rooms in hospitals. Eighty-two were performed in non-medical institutions, and the remaining six items (such as those pertaining to the specialized nurse or mother and child health care specialists) did not mention a specified activity location. Of the 82 non-medical institutions, 26 were government and public organizations, and 22 were long-term care and welfare facilities. The remaining included education and care facilities, amusement facilities, and correctional institutions.

Finally, we analyzed the types of practice of registered nurses at each location type (medical or non-medical institution) according to the framework developed in this study. The most common practices of registered nurses at medical institutions were the “Client-oriented role,” followed by the “Delivery-oriented role” (Table 3). The most common type of the former was the combined “Caregiver II/Referring Agent/Educator & Counselor.” The most common type of the latter was the “Coordinator & Leader.” Next, we analyzed 88 items together (the practice of registered nurses at non-medical institutions and unknown locations; Table 4). In these cases, the most common practices were the “Delivery-oriented role,” followed by the “Population-oriented role.” The most common type of the former was the combined “Coordinator & Leader.” The most common type of the latter was “Educator & Counselor.” Many of the roles the registered nurses performed in community were related to professional tasks they performed independently, that is, without the guidance of physicians, including “Caregiver III,” “Educator & Counselor,” and “Community Care Agent.” The other 22 items did not mention what the registered nurses did, despite identifying their place of activity.

This study explored the legal aspects of registered nurses’ roles and demonstrated that the laws have limitations in defining the present roles and practices of nurses.

As a result of examining the workforce allowed to perform the 119 items, 85 could be performed by people in multiple types of occupation. Of those 85 items, 19 could be performed by both registered nurses and nurse assistants still conduct the same tasks without distinction, especially outside the medical institutions. After the Medical Service Act (“the Act”) was revised in 2015, the scope of practice between registered nurses and nurse assistants was distinguished clearly [27]. According to the Act, nurse assistants perform duties delegated by registered nurses, and registered nurses guide nurse assistants. However, since the Act only applies in medical institutions, role ambiguity for nurses in the community still remains. This is problematic because if the scope of practice between different types of nursing staff is mixed and without standards, and the collaborative relationship between team members on nursing teams can malfunction [28]. As a result, this may risk the safety of people receiving nursing services [29]. There are ways to address these issues discussed. First, clear standards for the practice of nursing personnel should be established. Subsequently, many of the laws that currently prescribe the practice of nursing personnel should be revised in accordance with these standards. Similarly, integration of the regulations of nursing practices that currently exist in 64 separate laws into one comprehensive law related to nursing would be beneficial. Countries, responsible for the management of health professionals' licenses, define and regulate the scope of practice for these practitioners by law [45]. Thus, changes in the law are the most effective ways to improve the regulation of nursing practices. In Korea, the creation of such a “Nursing Act” has long been the legislative campaign of the Korean Nursing Association (KNA). Making laws is a difficult process because it is closely intertwined with various interest groups and is subject to political, social, and cultural pressures [530]. Registered nurses must first be interested in policy and law to exert their influence in the process of law enactment. They should take the lead in building social consensus regarding the need for nursing policy improvement. Furthermore, to improve leadership in the nursing community, nursing students should be taught to understand social issues related to nursing and to participate in policy-making processes by learning about the policy-making processes and nursing policies that influence the work of nurses and the health of the people [31]. Moreover, general nursing education curriculum lacks components of community-based primary care [32]. Thus, it is necessary to develop curriculum from various perspectives beyond medical institutions so that nursing students can grow into a new generation of registered nurses.

In addition, although relevant laws are designed for nurses to be assigned in specific places, 22 among the 119 items offered no specificity regarding what nursing tasks should be performed. This lack of specificity generates ambiguity when it comes to medical liability cases, especially those that occur in non-medical institutions. Such uncertainty in the scope of practice creates confusion and may even make registered nurses uncomfortable when tasked with performing certain functions as unclear guidance on what is and what is not licensed medical practice triggers questions of accountability [33]. In Korea, there are qualification certificates for specialized nurses who are similar to advanced practice nurses in the US. This qualification and acquisition procedure is stipulated in the Medical Service Act. However, the scope of practice is not prescribed, so there is some confusion in the field. For example, in 2010, the Supreme Court ruled that anesthetic actions, when performed by specialized nurses in anesthesia, were unlicensed medical practices [34]. After that, the Medical Service Act was revised in 2018 to solve these problems. The revised act will be implemented in 2020 and is expected to reduce confusion in the field.

It must be noted, however, we only analyzed statutes in this study. Therefore, the results do not reflect the situation in the field, such as whether nurses are actually working according to the statutes and are being placed as required. In the future, it is necessary to investigate whether nurses in the community are fully involved and performing the roles prescribed by law. Moreover, to develop a broader international perspective, additional research comparing the laws on nursing in other countries facing similar challenges should also be conducted using the framework developed in this study.

This study was the first to analyze the legal aspects of the scope of registered nurses' roles by examining the entirety of Korean law. The framework covering the full field that is not confined only to a certain place was developed as a classification system regarding nurses' roles. The results of this research could be used to improve laws and policies related to nurses' roles worldwide, as well as in Korea.

According to the results of the study, some nursing tasks can be performed by both registered and non-registered nurses, while some tasks are performed only by nurses with additional expertise beyond the registered nurses' license. Analysis results also revealed that the roles of registered nurses have exceeded the traditional role of medical care assistants in medical institutions to becoming a core workforce in the community and in primary care. Therefore, to match the enhanced scope and responsibilities of registered nurses and to appropriately recognize, guide, and hold accountable these nurses, laws and policy must reflect these changes. In doing so, these updated laws and policies will ultimately serve as a basis for improving the quality and safety of nursing services.

1. Clarke D. Chapter 10. Law, regulation and strategizing for health. In : Schmets G, Rajan D, Kadandale S, editors. Strategizing National Health in the 21st Century: A Handbook. Geneva: World Health Organization;2016. p. 1–18.

2. Gostin LO, Wiley LF. Public health law: Power, duty, restraint. 3rd ed. Oakland (CA): University of California Press;2016. p. 73–225.

3. Holcombe RG. Eliminating scope of practice and licensing laws to improve health care. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2003; 31(2):236–246. DOI: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2003.tb00084.x.

4. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Health workforce policies in OECD countries [Internet]. Paris: OECD;c2016. cited 2019 Jul 12. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/Health-workforce-policies-in-oecd-countries-Policy-brief.pdf.

5. Dower C, Moore J, Langelier M. It is time to restructure health professions scope-of-practice regulations to remove barriers to care. Health Affairs. 2013; 32(11):1971–1976. DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0537.

6. Berry JM, Wilcox C. The interest group society. 6th ed. New York: Taylor & Francis;2018. p. 1–18.

7. Fairman JA, Rowe JW, Hassmiller S, Shalala DE. Broadening the scope of nursing practice. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2011; 364(3):193–196. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp1012121.

8. International Council of Nurses (ICN). Scope of nursing practice and decision-making framework toolkit [Internet]. Geneva: ICN;c2010. cited 2019 Mar 30. Available from: https://www.icn.ch/nursing-policy/regulation-and-education.

9. World Health Organization (WHO). Nursing and midwifery in the history of the World Health Organization 1948-2017 [Internet]. Geneva: WHO;c2017. cited 2019 Mar 30. Available from: https://www.who.int/hrh/resources/Nursing-and-Midwifery-in-History-of-WHO/en/.

10. Yoder-Wise PS. Leading and managing in nursing. 6th ed. St. Louis (MO): Elsevier Mosby;2015. p. 167–182.

11. International Council of Nurses (ICN). Nursing regulation [Internet]. Geneva: ICN;c2013. cited 2019 Jan 30. Available from: https://www.icn.ch/sites/default/files/inline-files/B04_Nsg_Regulation.pdf.

12. Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI). A study on the improvement plan of the labor standards act [Internet]. Cheongju: KHIDI;c2013. cited 2018 Jun 1. Available from: https://www.khidi.or.kr/board/view?pageNum=21&rowCnt=10&menuId=MENU00085&maxIndex=00001006629998&minIndex=00001005599998&schType=0&schText=&categoryId=&continent=&country=&upDown=0&boardStyle=&no1=581&linkId=100655.

13. Kim J. A reasonable nursing resources reorganization plan through enactment of nurse act. Ilkam Law Review. 2015; 32:215–261.

14. Shin HW, Yeo NG. Current issues and tasks in health policy. Health and Welfare Forum. 2019; (267):44–57.

15. Lee S, Bae B. Nursing service R&D strategy based on policy direction of Korean government supported research and development. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing Administration. 2016; 22(1):67–79. DOI: 10.11111/jkana.2016.22.1.67.

16. Bowen GA. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal. 2009; 9(2):27–40. DOI: 10.3316/QRJ0902027.

17. Manning JF. Textualism and legislative intent. Virginia Law Review. 2005; 91:419–450. DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.2853690.

18. Epstein L, Segal JA, Victor JN. Dynamic agenda-setting on the United States supreme court: An empirical assessment. Harvard Journal on Legislation. 2002; 39(2):395–433. DOI: 10.7910/DVN/WIBHTC.

19. Kim JG. Textualism in the U.S. supreme court opinions. Study on The American Constitution. 2010; 21(3):285–311.

20. International Council of Nurses (ICN). International Council of Nurses and nursing now welcome 2020 as international year of the nurse and the midwife [Internet]. Geneva: ICN;c2019. cited 2019 Jul 6. Available from: https://www.icn.ch/news/international-council-nurses-and-nursing-now-welcome-2020-international-year-nurse-and-midwife.

21. International Council of Nurses (ICN). Nursing definitions [Internet]. Geneva: ICN;c2019. cited 2019 Mar 30. Available from: https://www.icn.ch/nursing-policy/nursing-definitions.

22. Mallik M, Hall C, Howard D. Nursing knowledge and practice: Foundations for decision making. 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Baillière Tindall;2009. p. 20–40.

23. Clark MJD. Community health nursing: Advocacy for population health. 5th ed. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Pearson Prentice Hall;2008. p. 2–24.

24. World Health Organization (WHO). Training modules for the syndromic management of sexually transmitted infections [Internet]. Geneva: WHO;c2007. cited 2019 Aug 3. Available from: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/rtis/9789241593407index/en/.

25. Hitchcock JE, Schubert PE, Thomas SA. Community health nursing: Caring in action. 2nd ed. Clifton Park (NY): Thomson/Delmar Learning;2003. p. 460–461.

26. American Nurses Association. Nursing: scope and standards of practice. 3rd ed. Silver Spring (MD): American Nurses Association;2015. p. 6–27.

27. Lee Y, Choi S, Kim I, Kang SJ. A study on reorganization of service and qualification management between nurse and nurse assistant: Focusing on policy stream model by Kingdon. Health and Social Welfare Review. 2018; 38(1):489–519. DOI: 10.15709/hswr.2018.38.1.489.

28. Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna H, Gillen P. Nurses', midwives' and patients' perceptions of trained health care assistants. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005; 50(4):345–355. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03399.x.

29. Hwang JI, Ahn J. Teamwork and clinical error reporting among nurses in Korean hospitals. Asian Nursing Research. 2015; 9(1):14–20. DOI: 10.1016/j.anr.2014.09.002.

30. Grossmann M. Interest group influence on US policy change: An assessment based on policy history. Interest Groups & Advocacy. 2012; 1(2):171–192. DOI: 10.1057/iga.2012.9.

31. Ellenbecker CH, Fawcett J, Jones EJ, Mahoney D, Rowlands B, Waddell A. A staged approach to educating nurses in health policy. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice. 2017; 18(1):44–56. DOI: 10.1177/1527154417709254.

32. Wojnar DM, Whelan EM. Preparing nursing students for enhanced roles in primary care: The current state of prelicensure and RN-to-BSN education. Nursing Outlook. 2017; 65(2):222–232. DOI: 10.1016/j.outlook.2016.10.006.

33. Kim KR. Advanced practice nurse system and unlicensed medical practice. The Korean Society of Law and Medicine. 2010; 11(1):173–198.

34. Court of Korea. [25 March 2010 Important Ruling] A case regarding a specialized nurse in anesthesia (according to the 'medical service act') [Internet]. Seoul: Court of Korea;c2010. cited 2018 Jun 1. Available from: http://www.scourt.go.kr/portal/news/NewsViewAction.work?seqnum=2445&gubun=4&searchOption=&searchWord=.

- TOOLS

- ORCID iDs

-

Sungkyoung Choi

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0744-2445Seung Gyeong Jang

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9121-3439 - Similar articles

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download