Abstract

Metastatic prostate cancer is a heterogeneous disease entity. Men without prior androgen deprivation therapy exposure are termed metastatic castration sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC). The goal of this article is to update the reader on the rapidly changing landscape of treatment for men with mCSPC. Along with the options available to the clinician for treatment of men with mCSPC, the care of these patients has evolved into a multi-disciplinary field with expanding roles for medical, urologic, and radiation oncologists.

Prostate cancer is the most common non-cutaneous cancer diagnosed in American men, and it is responsible for the second-most cancer related deaths, behind lung cancer [1]. Of the estimated 175,000 new cases of prostate cancer that will be diagnosed in 2019, 6% will present with de novo metastatic disease and still more patients each year will develop metastasis despite prior therapy with curative intent [1].

Metastatic prostate cancer is a heterogeneous disease entity, and two broad categories exist to classify men with advanced prostate cancer based on their exposure to continuous androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). Men without this prior exposure and especially those who are discovered de novo, where the cancer is most likely to demonstrate a dramatic and sustained response to ADT, are termed metastatic castration sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC). For those patients whose disease progresses, either radiographically or biochemically, despite ADT administration, an entirely separate stratification is applied. In this instance, patients are most appropriately referred to as metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). These designations have implications for patient management, and strategies and treatments that are available for these patients are aimed at converting metastatic prostate cancer into a chronic, albeit incurable, state [2].

The goal of this article is to update the reader on the rapidly changing landscape of treatment for men with mCSPC prostate cancer. Prior to 2014, the mainstay of treatment for these patients was monotherapy using chemical or surgical castration [3]. Since 2014, this space has expanded rapidly with clinical trials demonstrating improved survival by the addition of 5 new U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved agents [4]. Such strides have been made at inducing remission in castration sensitive prostate cancer patients with these modalities that the latest frontier is now turning back to treatment of the primary tumor—an effort considered futile merely 6 years ago.

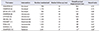

Along with the options available to the clinician for treatment of men with mCSPC, the care of these patients has evolved into a multi-disciplinary field with expanding roles for medical, urologic, and radiation oncologists. Patients with mCSPC will derive significant benefits include improved overall survival through access to these new combination treatments, and this can only be achieved through provider awareness and access to these novel therapeutics. Maintenance of up-to-date knowledge across these specialties is, and will continue to be, essential to the ability of providers to apply individualized therapy to patients in this complex space (Table 1) [567891011121314].

Traditionally, docetaxel systemic chemotherapy was reserved for patients in the mCRPC space, but 3 trials analyzed in aggregate [15] have confirmed its efficacy at improving survival when given with ADT for mCSPC. The CHAARTED (Chemohormonal Therapy Versus Androgen Ablation Randomized Trial for Extensive Disease in Prostate Cancer) trial randomized 397 patients to ADT+docetaxel and compared them with 393 patients undergoing ADT alone [5]. To date, there has been roughly a 40% improvement in clinical progression free survival, biochemical free survival and median overall survival with addition of docetaxel. Similar results were confirmed in arm C of the STAMPEDE (Systemic Therapy in Advancing or Metastatic Prostate Cancer: Evaluation of Drug Efficacy) trial which demonstrated a 38% improvement in biochemical free survival and 27% improvement in overall survival with docetaxel [6]. Notably, initial results from the French/Belgian GETUG-AFU 15 trial were discordant from CHAARTED and STAMPEDE showing no statistically significant improvement in overall survival with the addition of chemotherapy over ADT alone [7]. However, a recent meta-analysis of CHAARTED, STAMPEDE and GETUG-AFU 15 has confirmed the efficacy of 6 cycles of docetaxel being safe and effective at prolonging survival in mCSPC with good long-term patient reported tolerability at the cost of short-term quality of life detriments [15].

Not only did CHAARTED demonstrate, for the first time, that chemo/hormonal therapy administered earlier in the metastatic natural history convey significant survival advantages in prostate cancer, but also it established the importance of disease volume as a marker of patients who benefit from the most aggressive treatments. In CHAARTED, the most significant survival advantage afforded to recipients of docetaxel were those with high volume metastatic disease, defined as >4 bone lesions or bone lesions outside the axial skeleton or presence of visceral metastasis. Low volume, or oligometastatic, patients did not significantly benefit [5]. Other trials have adopted the same disease burden definition (STAMPEDE) and since CHARRTED was released this definition of high-volume versus low-volume disease burden has becomes perhaps the single most important parameter for guiding newly diagnosed metastatic patients in their first steps down the therapeutic pathway.

The STAMPEDE trial also included Arm G which randomized patients in 1:1 fashion to receive ADT alone or ADT plus 1,000 mg of abiraterone acetate with 5 mg of daily prednisone [8]. The primary endpoint of the study was overall survival and secondary endpoints included radiologic and prostatic specific antigen (PSA) progression as well as cancer-specific survival. Addition of abiraterone and prednisone was shown to improve overall survival by 37% at 3 years of follow-up, and all secondary endpoints were met with significant improvements as well. A similarly designed trial, LATITUDE, also compared ADT alone to patients receiving abiraterone plus prednisone with the caveat that patients particularly at high-risk were studied in this trial [9]. High-risk was defined as having the presence of two stratifying criteria including ≥3 bone metastases, Gleason Score ≥8, or visceral metastasis. Overall survival was again the primary endpoint with the same secondary endpoints as STAMPEDE. As with STAMPEDE, the overall survival benefit for patients receiving abiraterone in LATITUDE was 38% and all secondary endpoints demonstrated improvement with combination therapy.

Two recently released trials have investigated the role of androgen receptor (AR) targeted therapy with enzalutamide for patients with mCSPC. The ARCHES trial randomized men in 1:1 fashion to receiving 160 mg per day of enzalutamide with ADT or ADT with placebo [10]. Patients were stratified according to CHAARTED disease volume and receipt of prior docetaxel. Unlike trials with abiraterone, the primary endpoint in ARCHES was progression-free survival. Men taking enzalutamide were shown to have a 61% reduction in progression or death while on therapy. Importantly, Grade 3 toxicity rates were similar between patients on enzalutamide and placebo (24.3% vs. 25.6%). The ENZAMET trial was powered for overall survival as the primary endpoint and similarly compared men taking enzalutamide to those on “standard care” with an open-label antiandrogen therapy [11]. Enzalutamide was shown to improve overall survival by 33%. Secondary endpoints such as PSA and clinical progression-free survival were also improved with enzalutamide.

Another AR targeting agent, apalutamide, has received approval in the mCSPC space based on results from the TITAN trial [12], which compared 240 mg of apalutamide plus ADT to ADT and placebo. At 24 months of follow-up, the improvement in overall survival with apalutamide was 33%. Finally, the results of the ARASENS trial will determine if the unique AR agent darolutamide has efficacy in mCSPC for patients undergoing docetaxel chemotherapy.

In considering the options now available to practitioners for the initial treatment of mCSPC—ADT alone, docetaxel, abiraterone plus prednisone, enzalutamide, apalutamide, and likely soon darolutamide—two important questions remain to be answered with high-level data. First, the optimum sequencing of these therapies is unknown as is the efficacy of combining or switching between AR targeted therapies. Second, the duration of AR therapy once a response to treatment has been sustained is not adequately defined by the phase 3 trials which support their use. For now, the choice of which treatment to engage remains an individualized decision with disease burden, cost [16], toxicity and performance status [17] as leading factors to consider when challenged with these patients.

Recently, two trials have been released examining the effect of radiation to the primary tumor in patients with metastatic disease. The HORRAD trial randomized men with bone-only metastasis and PSA above 20 to ADT plus radiation versus ADT alone [13]. Radiation in this trial was external beam radiation therapy at a dose of 70 Gy in 35 fractions or 58 Gy in 19 fractions. The primary endpoint of overall survival was not achieved, with the 10% improvement in survival among those receiving radiation not reaching statistical significance. However, the secondary endpoint, time-to-PSA-recurrence, was significantly improved by 22% in the radiation group. Interestingly, the largest effect of radiation on the secondary endpoint was seen in men with low-volume bony disease, defined as fewer than 5 lesions, although this finding was obtained only through subgroup analysis for which the study was not adequately powered.

Arm H of the STAMPEDE trial randomized men with mCSPC to standard care, defined as ADT or ADT plus docetaxel, or standard care plus radiation [14]. Applications of radiation were in 55 Gy over 20 fractions or 36 Gy over 6 fractions. A prespecified subgroup analysis stratifying patients based on volume of disease according to CHAARTED criteria was planned prior to initiation of the study. In terms of the overall cohort, the 8% improvement in overall survival for the radiation group was not statistically significant. However, in subgroup analysis, the low-volume cohort had a 38% improvement in overall survival. Therefore, for now, prospective randomized evidence exists to treat the primary tumor in patients with low-volume mCSPC with radiation therapy. This question will be further tested in the PEACE-1 trial (NCT01957436) which seeks to randomize men to ADT plus docetaxel versus ADT plus docetaxel and abiraterone. Further stratification will then proceed to split patients into a local therapy arm with radiation versus no local therapy.

A new phase 3 randomized trial of standard systemic therapy (SST) versus SST plus definitive surgery or radiation for patients with mCSPC is currently enrolling. SWOG 1802 (NCT03678025) will administer 6 months of SST therapy to participants followed by randomization to either surgery or radiation versus observation. High-volume as well as low-volume metastatic patients are acceptable for enrollment, however prior treatment with docetaxel is an exclusion criterion.

Only two prospective trials exist for treatment of individual metastatic sites in mCSPC. The phase 2 STOMP trial tested surgery or radiation to metastatic sites in patients with positron emission tomography and computed tomography avid lesions against observation with a primary end-point of hormone-therapy free survival [18]. Unfortunately, treatment of metastatic sites was not significantly associated with time off of ADT and quality of life between the observation and treatment arms were similar as well. The POPSTAR trial also tested radiation therapy to metastatic sites in 33 men followed for local progression and freedom from ADT at median of 24 months [19]. Nearly 7% of patients experienced local progression despite radiation therapy to targeted lesions and 52% progressed to treatment with ADT during the study period. Until phase 3 trial data is available, metastasis-directed therapy for mCSPC remains investigatory.

The landscape of treatments available for patients with mCSPC is rapidly changing, but several themes have arisen that constitute the foundation for our approach to these challenging cases. First, early involvement of a multidisciplinary team (medical oncology, radiation oncology, clinical trials research) ensures that patients receive individualized care among options that so far have no high-level data for discrimination. Second, continuous ADT remains the backbone of therapy and it is generally recommended to continually apply centrally acting androgen axis suppression in combination with novel agents discussed above. Third, taxane-based systemic chemotherapy with appears to be most impactful for those patients presenting with high-volume metastatic disease burden. Fourth, the correct sequence of non-chemotherapeutic agents against the androgen axis or AR remains in question (abiraterone, enzalutamide, apalutamide), but we generally agree that current high-level evidence is lacking to support switching between therapies once patients progress on an AR-targeted therapy. Lastly, the treatment of the primary tumor or selected metastasis-directed therapies should be applied only in the context of a clinical trial, as true efficacy for these strategies has yet to be demonstrated. Importantly, we await the currently ongoing and future randomized trials which will hopefully further advance our knowledge in the evolution of the changing landscape of mCSPC.

Figures and Tables

References

2. Montgomery RB, Mostaghel EA, Vessella R, Hess DL, Kalhorn TF, Higano CS, et al. Maintenance of intratumoral androgens in metastatic prostate cancer: a mechanism for castration-resistant tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2008; 68:4447–4454.

3. Scher HI, Sawyers CL. Biology of progressive, castration-resistant prostate cancer: directed therapies targeting the androgen-receptor signaling axis. J Clin Oncol. 2005; 23:8253–8261.

4. Weiner AB, Nettey OS, Morgans AK. Management of Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer (mHSPC): an evolving treatment paradigm. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019; 20:69.

5. Sweeney CJ, Chen YH, Carducci M, Liu G, Jarrard DF, Eisenberger M, et al. Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015; 373:737–746.

6. James ND, Sydes MR, Clarke NW, Mason MD, Dearnaley DP, Spears MR, et al. STAMPEDE investigators. Addition of docetaxel, zoledronic acid, or both to first-line long-term hormone therapy in prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): survival results from an adaptive, multiarm, multistage, platform randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016; 387:1163–1177.

7. Gravis G, Fizazi K, Joly F, Oudard S, Priou F, Esterni B, et al. Androgen-deprivation therapy alone or with docetaxel in non-castrate metastatic prostate cancer (GETUG-AFU 15): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013; 14:149–158.

8. James ND, de Bono JS, Spears MR, Clarke NW, Mason MD, Dearnaley DP, et al. STAMPEDE Investigators. Abiraterone for Prostate Cancer Not Previously Treated with Hormone Therapy. N Engl J Med. 2017; 377:338–351.

9. Fizazi K, Tran N, Fein L, Matsubara N, Rodriguez-Antolin A, Alekseev BY, et al. LATITUDE Investigators. Abiraterone plus prednisone in metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017; 377:352–360.

10. Armstrong AJ, Szmulewitz RZ, Petrylak DP, Holzbeierlein J, Villers A, Azad A, et al. ARCHES: a randomized, phase III study of androgen deprivation therapy with enzalutamide or placebo in men with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019; 37:2974–2986.

11. Davis ID, Martin AJ, Stockler MR, Begbie S, Chi KN, Chowdhury S, et al. ENZAMET Trial Investigators and the Australian and New Zealand Urogenital and Prostate Cancer Trials Group. Enzalutamide with standard first-line therapy in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019; 381:121–131.

12. Chi KN, Agarwal N, Bjartell A, Chung BH, Pereira de Santana Gomes AJ, Given R, et al. TITAN Investigators. Apalutamide for metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019; 381:13–24.

13. Boevé LMS, Hulshof MCCM, Vis AN, Zwinderman AH, Twisk JWR, Witjes WPJ, et al. Effect on survival of androgen deprivation therapy alone compared to androgen deprivation therapy combined with concurrent radiation therapy to the prostate in patients with primary bone metastatic prostate cancer in a prospective randomised clinical trial: data from the HORRAD trial. Eur Urol. 2019; 75:410–418.

14. Parker CC, James ND, Brawley CD, Clarke NW, Hoyle AP, Ali A, et al. Systemic Therapy for Advanced or Metastatic Prostate cancer: Evaluation of Drug Efficacy (STAMPEDE) investigators. Radiotherapy to the primary tumour for newly diagnosed, metastatic prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018; 392:2353–2366.

15. Sathianathen NJ, Philippou YA, Kuntz GM, Konety BR, Gupta S, Lamb AD, et al. Taxane-based chemohormonal therapy for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: a Cochrane Review. BJU Int. 2019; 124:370–372.

16. Pollard ME, Moskowitz AJ, Diefenbach MA, Hall SJ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of treatments for metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer. Asian J Urol. 2017; 4:37–43.

17. Sharma AP, Mavuduru RS, Bora GS, Devana SK, Singh SK, Mandal AK. STAMPEDEing metastatic prostate cancer: CHAARTing the LATITUDEs. Indian J Urol. 2018; 34:180–184.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download