Abstract

Purpose

Local anesthetics can decrease postoperative pain after appendectomy. This study sought to verify the efficacy of bupivacaine on postoperative pain and analgesics use after single-incision laparoscopic appendectomy (SILA).

Methods

Between March 2014 and October 2015, 68 patients with appendicitis agreed to participate in this study. After general anesthesia, patients were randomized to bupivacaine or control (normal saline) groups. The assigned drugs were infiltrated into subcutaneous tissue and deep into anterior rectus fascia. Postoperative analgesics use and pain scores were recorded using visual analogue scale (VAS) by investigators at 1, 8, and 24 hours and on day 7. All surgeons, investigators and patients were blinded to group allocation.

Results

Thirty patients were allocated into the control group and 37 patients into bupivacaine group (one patient withdrew consent before starting anesthesia). Seven from the control group and 4 from the bupivacaine group were excluded. Thus, 23 patients in the control group and 33 in the bupivacaine group completed the study. Preoperative demographics and operative findings were similar. Postoperative pain and analgesics use were not different between the 2 groups. Subgroup analysis determined that VAS pain score at 24 hours was significantly lower in the bupivacaine group (2.1) than in the control group (3.8, P = 0.007) when surgery exceeded 40 minutes. During immediate postoperative period, bupivacaine group needed less opioids (9.1 mg) than control (10.4 mg).

Laparoscopic appendectomy has advantages of less postoperative pain, less wound infection and better cosmetic results than open appendectomy (OA) [12]. Single-incision laparoscopic appendectomy (SILA) is safe and feasible for performing appendectomy and can be an alternative to conventional 3-port laparoscopic appendectomy (CLA), even with enhanced cosmetic effects [34]. Concerning postoperative pain, SILA was superior or equal to CLA [4]. However, other authors reported that SILA was associated with greater pain and required more analgesics on exertion [56]. Greater postoperative pain might be a limitation to SILA. To maximize the advantages of SILA, we sought methods to decrease postoperative pain.

Because an appendectomy incision is small, local anesthetic agents are used to decrease wound pain. Local anesthesia has been effective in some studies [789] but not others [101112]. These studies included OA, CLA, and SILA. Because OA is performed after splitting multiple muscle layers, and CLA has 3 incisions, local anesthesia may not be enough to decrease pain. For SILA, the involved abdominal wall layers consist of skin, subcutaneous fat, linea alba, and peritoneum. Entering the peritoneal cavity is much easier with SILA than OA.

To the best of our knowledge, only one report has addressed postoperative pain control with local anesthesia after SILA, though it was a retrospective study [7]. This study sought to verify the efficacy of bupivacaine on postoperative pain and analgesics use after SILA using a prospective double-blind randomized study design.

Between March 2014 and October 2015, 68 patients agreed to participate. All included patients met the following criteria: clinically or radiologically suspicious uncomplicated acute appendicitis; 19–60 years of age; normal hematologic, hepatic and renal function; understanding of the process and aim of this study, with voluntary signed informed consent.

The exclusion criteria were: clinically or radiologically suspicious periappendiceal abscess or perforation; abscess or perforation identified during surgery; additional trocar insertion during surgery; patients unfit for SILA as determined by the surgeon; previous abdominal surgery with periumbilical scar; patients with allergy or hypersensitivity to bupivacaine or other amide drugs; combined resection of other organs; patients with serious medical comorbidities; pregnancy; and, inability/refusal to sign the informed consent form.

Once patients were enrolled, they were sent to the operating room and underwent general anesthesia. During induction, fentanyl and other drugs, including lidocaine, propofol, and muscle relaxant were administered intravenously. Doses were determined by anesthesiologist according to the patients' weight. After intubation, the circulating nurse removed the seal of a premade randomization table and assigned the patients to the control or bupivacaine group. The drug was delivered in an unmarked 10-mL syringe. None of the surgeons, patients, nor the investigator, in the ward knew which drug was used until the final survey.

Under general anesthesia, after complete preparation of the operation field, intervening drugs (10 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine or normal saline) were infiltrated into the subcutaneous tissue around the umbilicus just before the incision [1314]. The incision was made transumbilically from the upper to lower edge. Subcutaneous fat was divided bluntly down to the fascia. After identifying the linea alba, the needle was advanced deep to anterior rectus fascia about 2–3 mm on both sides and another 10 mL of drugs was infiltrated [1315]. The fascia incision was made by electrocautery down to the peritoneum. The typical length of the fascia incision was 25–30 mm. A single-incision laparoscopy port was inserted. Entering the abdominal cavity, appendiceal vessels were ligated with a surgical clip and divided. Appendix bases were ligated with an endo-loop or surgical clip according to the surgeon's preferences. Appendix bases were transected and extracted through the umbilicus. Peritoneal fluid was aspirated and irrigated with normal saline, if needed. An additional trocar was inserted for difficult cases, which were excluded from the analysis. The fascia was closed with 1–0 polyglactin interrupted sutures. Subcutaneous tissue and dermis were approximated with 3-0 polyglactin sutures. Aseptic dressing was applied.

In the postanesthetic care unit (PACU), fentanyl was used intravenously for postoperative pain control. It was given every 10 minutes in 50-µg increments until the visual analogue scale (VAS) rating of pain was less than 3. Fentanyl titration was discontinued if the patient had peripheral oxygen saturation <94% or a respiratory rate <10 breaths/min. If severe pain persisted or there were chills, 25 mg of pethidine was injected intravenously up to 2 times every 10 minutes. When the pain could be tolerated and the vital signs were stable, the patient was transferred from the PACU to the general ward. After transfer, 30 mg of ketorolac was administered intravenously, if needed. If the pain was not controlled (VAS ≥ 5) with the initial dose, further doses were given and these were recorded with time. No patient used patient-controlled analgesia.

The patients were permitted to drink 6 to 8 hours after surgery, and resumed a soft blended diet 12 hours after surgery. Patients were discharged when diet and pain were tolerated, which was usually 2 days after surgery. If pain persisted at the time of discharge, oral analgesics were given for 3 or 4 days. Follow-up examination was done on postoperative day 7.

Primary outcome was postoperative pain. Secondary outcome was postoperative analgesics use. Overall dose of opioids used in PACU was converted into equianalgesic dose of morphine by potency [16]. Pain scores were recorded at 1, 8, and 24 hours using a VAS [17]. After discharge, the pain score was recorded at outpatient department on postoperative day 7 in the same manner. Postoperative wound state and other complications were evaluated. The analgesics used in the PACU and general ward were recorded.

The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS ver. 18.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). Nominal variables were analyzed with chi-square test or Fisher exact test. Ordinal variables were analyzed with Mann-Whitney U-test and numerical variables were analyzed with Student t-test.

This study was conducted under the approval of the Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 13-054). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

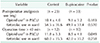

Sixty-eight patients were enrolled. One patient withdrew consent before starting anesthesia. The 67 patients were randomized into the control group (n = 30) and bupivacaine group (n = 37). Eleven patients were excluded due to abscess/perforation (n = 2), additional trocar insertion (n = 3), combined resection (n = 1), protocol violation (n = 4), and consent withdrawal (n = 1). Finally, 56 patients (23 in the control group and 33 in the bupivacaine group) were analyzed. Demographic data showed no significant difference for sex, age, body mass index (BMI), medical comorbidities, past abdominal surgery, abdominal tenderness, fever (≥37.5℃), and leukocytosis (>11,000 µL). Operative results showed no difference for operation time, severity of appendicitis, postoperative hospital stay, and wound complications, which were seroma in 1 patient in the bupivacaine group and 2 superficial surgical site infections in both groups (Table 1).

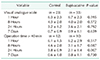

Control patients stayed in the PACU for 35 ± 6.6 minutes and bupivacaine for 34 ± 7.4 minutes (P = 0.643). In the PACU, the control and bupivacaine group needed 10.4 ± 4.0 mg and 9.1 ± 3.2 mg of morphine, respectively (P = 0.183) (Table 2). In the general ward, the first dose of ketorolac was given in 1.5 ± 1.9 hours and 1.6 ± 3.5 hours after transfer, in the same respective group order (P = 0.877). The second doses were given after 12.1 ± 9.8 hours and 12.9 ± 7.6 hours, respectively (P = 0.818). The overall use of ketorolac in the general ward did not differ between the 2 groups (54.5 ± 36.6 mg vs. 49.1 ± 33.4 mg, P = 0.570). VAS pain scores were 6.3 ± 2.3 in the control group and 6.7 ± 2.3 in the bupivacaine group 1 hour after transfer to the general ward (P = 0.595) (Table 3). The scores decreased gradually after 8 and 24 hours, and on postoperative day 7 in both groups. There were no statistically significant differences between the control and bupivacaine groups.

In subgroup analysis, when the operation time exceeded 40 minutes (12 patients in the control group and 10 patients in the bupivacaine group), the control group required significantly more opioids (11.8 ± 3.3 mg) in the PACU than the bupivacaine group (8.5 ± 4.1 mg) (P = 0.049). At 24 hours, VAS in the control group (3.8) was significantly higher than in the bupivacaine group (2.1) (P = 0.007). The overall doses of ketorolac in the general ward were not significantly different (60.0 ± 35.5 mg in control and 42.0 ± 35.2 mg in bupivacaine, P = 0.258). VAS at 1 and 8 hours, and on postoperative day 7 did not differ significantly.

To reduce abdominal wound pain, the infiltration of local anesthetics was investigated after various types of appendectomy. In a randomized clinical trial (RCT), pain scores and analgesics requirement were reduced with bupivacaine in children after OA [9]. On the contrary, other RCTs did not demonstrate reduction of analgesics use with subcutaneous bupivacaine infiltration in children after OA [1011]. Two retrospective studies reported decreased use of analgesics with bupivacaine infiltration in adults after laparoscopic appendectomy [78]. Our study differs from these 2 prior retrospective studies in that we used local anesthesia for SILA in adults in a prospective, randomized setting. We sought the most effective method of infiltration. Ke et al. [14] showed that preincisional infiltration was more effective in decreasing pain than postincisional infiltration. Although other studies showed no difference between pre- and postincisional infiltration [1819], there was no study that preferred post-incisional infiltration. Consequentially, we chose preincisional infiltration. Subcutaneous and simultaneous infiltration into the fascia were known as more effective methods of decreasing postoperative pain [1520]. However, with these efforts to decrease postoperative wound pain after SILA, bupivacaine did not decrease postoperative pain or analgesics use, generally. In the PACU, intravenous opioids were used and the patients were transferred to general ward with VAS scores <3. However, the effect of the opioids did not last long. The postoperative pain scores in the general ward at 1 hour were high (VAS > 5) in both groups, which was an indication for additional intervention for pain control. The VAS scores decreased gradually with time and the overall doses of ketorolac did not different between the 2 groups.

Bupivacaine was infiltrated at the beginning of surgery. Thirty to 45 minutes after infiltration, the drug attains peak levels. Because the surgery ends around this time, we expected that analgesic use would be diminished during the immediate postoperative period. However, both groups needed similar doses of opioids in PACU. Bupivacaine infiltration was not enough to decrease immediate postoperative pain. The effect of fentanyl persists for a few hours [21] after administration in PACU. Even when the effect of local infiltration was masked by fentanyl, most patients needed an additional dose of analgesia 1 hour after transfer to the general ward. This means that the benefits of bupivacaine lacked clinical significance.

Although the overall pain score at 1, 8, and 24 hours and on postoperative day 7 did not differ significantly, use of opioids in the PACU and the pain scores at 24 hours were significantly lower in the bupivacaine group in patients with a longer operation time. And although it was not statistically significant, less analgesics were used in the bupivacaine group. Because the mean operation time was 41.2 ± 13.3 minutes, we performed subgroup analysis by operation times of 40 minutes. In longer operations, the wound would be stretched for a longer time. This can induce traction or ischemic nerve injury around the surgical incision causing neuropathic pain. It could produce more pain for longer periods. In this circumstance, bupivacaine prevented peripheral nerve sensitization, resulting in postoperative pain reduction for longer times than the pharmacological reaction [22]. However, we did not find a significant relation between operation time and pain. Operation time might be affected by other factors including the surgeon. In this study, 4 surgeons performed the surgeries and the operation time was different between surgeons. However, there was no significant difference in pain scores or other demographic characteristics. Although longer operation time showed a tendency for more effectiveness of bupivacaine, further study with more patients is needed to determine the relation to the effectiveness of bupivacaine. Since the subgroup analysis involved only 23 patients, this small number is one of the limitations of our study.

Although we randomized and monitored patients in a double-blind manner, the study population was not calculated prior to the study, which could make our results underpowered. We calculated the sample size retrospectively. Using the postoperative VAS score as the primary outcome for detecting one point of difference, an alpha value of 0.05, a beta value of 0.20, and statistical power of 80%, we got the sample numbers of 24 and 25 in each group (the drop rate was not considered) [23].

Drugs used for pain control varied. In the PACU, fentanyl and pethidine were used, and in the general ward, ketorolac was used. The total dose of analgesics in the PACU was converted into equianalgesic dose of morphine by potency for statistical convenience [16]. This is a reasonable and common approach. Pain was more severe during the immediate postoperative period, necessitating stronger analgesics. On the contrary, in the general ward, ketorolac was sufficient to control the pain. The doses of drugs used in the PACU and general ward were compared separately.

We used bupivacaine hydrochloride in this study. Bupivacaine liposome provides prolonged pain relief [24], and reduce opioid requirement in the first 72 hours after surgery [25]. Although the superiority of liposomal bupivacaine over bupivacaine hydrochloride has not been adequately established [24], the results might have differed if we had used liposomal bupivacaine. We injected 10 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine in the subcutaneous fatty tissue and another dose in the rectus fascia regardless of body weight. This dose was chosen because 20 mL of bupivacaine was sufficient for local excisions of small masses involving muscle fascia. In this study, the mean BMI was 23.3 ± 3.6 kg/m2, and there were 18 overweight patients (BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2). In obese patients (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), this dose might not be enough for pain control. However, only 3 obese patients were included in the study.

According to our study protocol, complicated appendicitis including periappendiceal abscess or perforated appendicitis should be excluded. Generally, gangrenous appendicitis is classified into complicated appendicitis. In this study, if the appendices showed gangrenous change during surgery despite preoperative images, that cases were excluded. However, if the pathologic reports were gangrenous, in contrast to the surgeon's gross findings, the cases were included. We excluded complicated appendicitis because it could cause generalized abdominal pain and make it difficult to distinguish from wound pain, which was assumed to be decreased by local anesthesia. However, we thought microscopic gangrenous appendicitis would not cause generalized abdominal pain and could be distinguished from wound pain. There were 3 pathologically proven gangrenous appendices.

In conclusion, bupivacaine was not efficient in decreasing pain and analgesics use after SILA. When surgery exceeded 40 minutes, bupivacaine use had greater association with less pain and less analgesics use.

Figures and Tables

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was conducted with research grants from Myongji Hospital (grant number: 2013-01-10).

Notes

References

1. Wei B, Qi CL, Chen TF, Zheng ZH, Huang JL, Hu BG, et al. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy for acute appendicitis: a metaanalysis. Surg Endosc. 2011; 25:1199–1208.

2. Wei HB, Huang JL, Zheng ZH, Wei B, Zheng F, Qiu WS, et al. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy: a prospective randomized comparison. Surg Endosc. 2010; 24:266–269.

3. Buckley FP 3rd, Vassaur H, Monsivais S, Jupiter D, Watson R, Eckford J. Single-incision laparoscopic appendectomy versus traditional three-port laparoscopic appendectomy: an analysis of outcomes at a single institution. Surg Endosc. 2014; 28:626–630.

4. Frutos MD, Abrisqueta J, Lujan J, Abellan I, Parrilla P. Randomized prospective study to compare laparoscopic appendectomy versus umbilical single-incision appendectomy. Ann Surg. 2013; 257:413–418.

5. Teoh AY, Chiu PW, Wong TC, Poon MC, Wong SK, Leong HT, et al. A double-blinded randomized controlled trial of laparoendoscopic single-site access versus conventional 3-port appendectomy. Ann Surg. 2012; 256:909–914.

6. Kim HO, Yoo CH, Lee SR, Son BH, Park YL, Shin JH, et al. Pain after laparoscopic appendectomy: a comparison of transumbilical single-port and conventional laparoscopic surgery. J Korean Surg Soc. 2012; 82:172–178.

7. Ahn SR, Kang DB, Lee C, Park WC, Lee JK. Postoperative pain relief using wound infiltration with 0.5% bupivacaine in single-incision laparoscopic surgery for an appendectomy. Ann Coloproctol. 2013; 29:238–242.

8. Cervini P, Smith LC, Urbach DR. The effect of intraoperative bupivacaine administration on parenteral narcotic use after laparoscopic appendectomy. Surg Endosc. 2002; 16:1579–1582.

9. Wright JE. Controlled trial of wound infiltration with bupivacaine for postoperative pain relief after appendicectomy in children. Br J Surg. 1993; 80:110–111.

10. Edwards TJ, Carty SJ, Carr AS, Lambert AW. Local anaesthetic wound infiltration following paediatric appendicectomy: a randomised controlled trial: time to stop using local anaesthetic wound infiltration following paediatric appendicectomy? Int J Surg. 2011; 9:314–317.

11. Jensen SI, Andersen M, Nielsen J, Qvist N. Incisional local anaesthesia versus placebo for pain relief after appendectomy in children--a double-blinded controlled randomised trial. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2004; 14:410–413.

12. Ko CY, Thompson JE Jr, Alcantara A, Hiyama D. Preemptive analgesia in patients undergoing appendectomy. Arch Surg. 1997; 132:874–877.

13. Randall JK, Goede A, Morgan-Warren P, Middleton SB. Randomized clinical trial of the influence of local subcutaneous infiltration vs subcutaneous and deep infiltration of local anaesthetic on pain after appendicectomy. Colorectal Dis. 2010; 12:477–479.

14. Ke RW, Portera SG, Bagous W, Lincoln SR. A randomized, double-blinded trial of preemptive analgesia in laparoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 1998; 92:972–975.

15. Khorgami Z, Shoar S, Hosseini Araghi N, Mollahosseini F, Nasiri S, Ghaffari MH, et al. Randomized clinical trial of subcutaneous versus interfascial bupivacaine for pain control after midline laparotomy. Br J Surg. 2013; 100:743–748.

16. Lacy CF, Armstrong LL, Goldman MP, Lace LL. Lexi-Comp's drug information handbook. 12th ed. Hudson (OH): Lexi-Comp, Inc.;2004. p. 1865.

17. Price DD, Bush FM, Long S, Harkins SW. A comparison of pain measurement characteristics of mechanical visual analogue and simple numerical rating scales. Pain. 1994; 56:217–226.

18. Molliex S, Haond P, Baylot D, Prades JM, Navez M, Elkhoury Z, et al. Effect of pre- vs postoperative tonsillar infiltration with local anesthetics on postoperative pain after tonsillectomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1996; 40:1210–1215.

19. Dahl V, Raeder JC, Erno PE, Kovdal A. Pre-emptive effect of pre-incisional versus post-incisional infiltration of local anaesthesia on children undergoing hernioplasty. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1996; 40:847–851.

20. Lohsiriwat V, Lert-akyamanee N, Rushatamukayanunt W. Efficacy of pre-incisional bupivacaine infiltration on postoperative pain relief after appendectomy: prospective double-blind randomized trial. World J Surg. 2004; 28:947–950.

21. Trescot AM, Datta S, Lee M, Hansen H. Opioid pharmacology. Pain Physician. 2008; 11:2 Suppl. S133–S153.

22. Meacham K, Shepherd A, Mohapatra DP, Haroutounian S. Neuropathic pain: central vs. peripheral mechanisms. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2017; 21:28.

23. Hulley SB, Cummings SR, Browner WS, Grady DG, Newman TB. Designing clinical research: an epidemiologic approach. 4 ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;2013.

24. Chahar P, Cummings KC 3rd. Liposomal bupivacaine: a review of a new bupivacaine formulation. J Pain Res. 2012; 5:257–264.

25. Hutchins J, Argenta P, Berg A, Habeck J, Kaizer A, Geller MA. Ultrasound-guided subcostal transversus abdominis plane block with liposomal bupivacaine compared to bupivacaine infiltration for patients undergoing robotic-assisted and laparoscopic hysterectomy: a prospective randomized study. J Pain Res. 2019; 12:2087–2094.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download