This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Background and Purpose

We aimed to determine the reliability and validity of a short form of the Korean Dementia Screening Questionnaire-Cognition (KDSQ-C) as a screening tool for cognitive dysfunction.

Methods

This study recruited 420 patients older than 65 years and their informants from 11 hospitals, and categorized the patients into normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia subgroups. The KDSQ-C was completed separately by the patients and their informants. We abstracted three components of the KDSQ-C and combined these components into the following four subscales: KDSQ-C-I (items 1–5, memory domain), KDSQ-C-II (items 1–5 & 11–15, memory domain+activities of daily living), KDSQ-C-III (items 1–5 & 6–10, memory domain+other cognitive domains), and KDSQ-C-IV (items 6–10 & 11–15, other cognitive domains+activities of daily living). The reliability and validity were compared between these four subscales.

Results

A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis of questionnaire scores provided by the patients showed that the areas under the ROC curves (AUCs) for the KDSQ-C, KDSQC-I, and KDSQ-C-II for diagnosing dementia were 0.75, 0.72, and 0.76, respectively; the corresponding AUCs for informant-completed questionnaires were 0.92, 0.89, and 0.92, indicating good discriminability for dementia.

Conclusions

A short form of the patient- and informant-rated versions of the KDSQ-C (KDSQ-C-II) is as capable as the 15-item KDSQ-C in screening for dementia.

Keywords: cognition, dementia, self report, self-assessment, questionnaire

INTRODUCTION

Korea has a periodic general health checkup program that screens for cognitive dysfunction using the Korean Dementia Screening Questionnaire-Cognition (KDSQ-C).

1 Our previous study recommended that the KDSQ-C should continue to be used in national medical checkups when an informant report is possible, since its discriminability for dementia does not differ from that of other dementia questionnaires.

2 Moreover, consistent data collection using the same questionnaire is important in a national health checkup system. Therefore, when an informant is not available, the KDSQ-C may be completed by the patient. However, discriminability is lower in patient-completed than informant-completed questionnaires.

The current version of the KDSQ-C is a semistructured questionnaire that includes 15 questions that assess 3 dimensions: memory impairment (items 1–5), other cognitive impairments including language impairments (items 6–10), and the ability to perform complex tasks in daily life (items 11–15). The KDSQ-C contains the response options of “never,” “sometimes,” and “frequently” that are scored as 0, 1, and 2, respectively.

1 The KDSQ-C was initially designed to be completed by reliable informants, although it is usually completed by the patients themselves when a caregiver is not available. The 15 items of the KDSQ-C are particularly difficult to complete for patients with dementia without help from such an informant. To circumvent this problem, we developed a short form of the KDSQ-C that maintains the content validity of the original standard scale and can be completed easily by patients with dementia when an informant is not available.

We constructed the short form of the KDSQ-C by dividing the original version into the following four subscales: KDSQ-C-I (items 1–5, memory domain), KDSQ-C-II (items 1–5 & 11–15, memory domain+activities of daily living), KDSQC-III (items 1–5 & 6–10, memory domain+other cognitive domains), and KDSQ-C-IV (items 6–10 & 11–15, other cognitive domains+activities of daily living). We compared the reliability and validity of the four subscales as a screening tool for cognitive dysfunction.

METHODS

Participants

This study recruited 420 patients [200 subjects with normal cognition, 50 patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), 120 patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD), and 50 patients with other dementias] older than 65 years and their informants from 11 hospitals in Korea (7 in Seoul, 3 in Gyeonggi-do, and 1 in Busan) from August 2017 to April 2018. These participants were recruited from the department of neurology or psychiatry of the outpatient clinic of each hospital or from the regional dementia centers of local districts (Mapo-gu, Yangcheon-gu, and Gangseo-gu) in Seoul. All of the patients were examined by highly experienced neurologists and psychiatrists and were classified into subjects with normal cognition, patients with MCI, and patients with dementia. The MCI and dementia subgroups were combined into the cognitive-impairment group. The subjects with normal cognition were cognitively and functionally normal, independent, and fulfilled the health-screening exclusion criteria of Christensen et al.

3 The Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores of the subjects with normal cognition were higher than 1.5 SDs above the norm. MCI was diagnosed based on the diagnostic criteria of Peterson.

45 The specific inclusion criteria for MCI were as follows: 1) self- and/or informant-reported cognitive decline, 2) cognitive impairment (of at least 1.5 SDs below the age- and education-adjusted norms) in at least one domain (executive function, memory, language, or visuospatial) in standard neuropsychological tests, 3) normal functional activities, and 4) lack of dementia according to the criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR).

6

Dementia was categorized into AD, vascular dementia, frontotemporal dementia, and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). AD was diagnosed based on the criteria for probable AD proposed by the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association

7 as well as the DSM-IV-TR.

6 Vascular dementia was diagnosed based on the appropriate DSM-IV-TR criteria.

6 Frontotemporal dementia was diagnosed based on previously reported criteria for frontotemporal dementia.

8 DLB was diagnosed based on the criteria for probable DLB proposed by the third report of the DLB Consortium.

9 Recruitment was limited to patients with very mild to moderate dementia with a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) score of 0.5, 1, or 2.

Patients with any of the following structural or laboratory testing abnormalities that could lead to cognitive decline were excluded: 1) head injury that resulted in loss of consciousness or cognitive impairment for longer than 1 hour, 2) previous history of cerebral hemorrhage or subarachnoid hemorrhage, 3) presence of a space-occupying brain lesion, 4) cognitive impairment associated with neurosyphilis, HIV infection, thyroid abnormalities, or vitamin B12 or folate deficiency, or 5) history of metabolic encephalopathy. This study excluded patients with any Axis I psychiatric disorder such as depression, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorder, as well as those with physical illnesses or disorders that could interfere with clinical investigations such as hearing or vision loss, aphasia, severe cardiac failure, severe respiratory illnesses, uncontrolled diabetes, malignancy, or hepatic failure or renal disorders with dialysis.

An informant had to be a caregiver who met the patient at least 3 days per week and spent more than 4 hours at each visit in order to ensure that they had an adequate understanding of the patient's condition. The informant also had to be available to participate in the research process including completing the questionnaire.

Clinical evaluations

We examined the baseline demographic data of the patients including age, sex, years of education, and past medical history and family history. All of the patients first completed the MMSE-Dementia Screening (MMSE-DS) questionnaire

10 and short form of the Geriatric Depression Scale (SGDS)

11 to evaluate their global cognition and possible presence of depression, respectively. Cognitive impairment groups were diagnosed based on the Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery or the Korean version of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Packet. Brain neuroimaging, such as CT or MRI, and laboratory tests including a complete blood test, vitamin B12, folate, homocysteine, syphilis, thyroid function test, and HIV were also performed. The KDSQ-C was completed separately by the patients and their informants to evaluate cognitive function and the ability to perform the activities of daily living.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as percentages, and continuous variables are presented as mean±SD or median and interquartile-range values. Group comparisons were performed using Student's t-test for normally distributed continuous variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for nonnormally distributed continuous variables, while the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used for categorical variables. We calculated the sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing dementia for the KDSQ-C and MMSE with receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Areas under the ROC curves (AUCs) with 95% CIs were generated to assess the diagnostic ability of each screening questionnaire, and AUCs were compared between instruments using the DeLong method. The AUC of a questionnaire was considered to be statistically significant when the p value was lower than 0.006 by applying Bonferroni correction considering the multiple-comparisons problem. The optimal cutoff score of questionnaire was selected when Youden's index was maximized by the ROC curve. Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) was also calculated. Correlations between patient- and informant-rated instrument scores were quantified using Spearman's correlation coefficient (ρ). The criterion for statistical significance was set at p<0.05. The Fisher r-to-z transformation (z score) was used to determine significant differences between correlation coefficients. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all of the participating centers. All patients and informants provided signed informed consents to participate in the study (IRB No. KC17QNDE0093).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

The detailed baseline demographic characteristics of the study participants were presented in our previous paper.

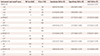

2 In brief, the sample consisted of 200 subjects with normal cognition, 50 patients with MCI, and 170 patients with dementia (

Table 1). The mean age at the time of assessment was older and the educational level was lower in the dementia group than in the normal cognition group. Thirty-four (20.0%) patients in the dementia group had a family history of dementia. There were 72, 70, and 27 patients in the dementia group with CDR scores of 0.5, 1, and 2, respectively (data not shown).

Comparison of questionnaire scores by group

Table 2 lists the MMSE and questionnaire scores in the normal, MCI, and dementia subgroups as evaluated by the patients and their informants. The MMSE-DS score was the highest in the subjects with normal cognition (27.3±1.9), followed by patients with MCI (24.3±3.2) and dementia (18.5±5.4). The patient-rated KDSQ-C (p-KDSQ-C) score was 3.9±3.5 in the subjects with normal cognition, 6.4±5.0 in the MCI patients, and 9.3±7.4 in the dementia patients; the corresponding p-KDSQ-C-I scores were 1.8±1.6, 2.8±2.3, and 3.8±2.8, respectively; those for p-KDSQ-C-II were 2.1±2.1, 3.8±3.2, and 5.9±5.1; those for p-KDSQ-C-III were 3.5±2.9, 5.4±3.9, and 7.2±5.1; and those for p-KDSQ-C-IV were 2.1±2.3, 3.6±3.3, and 5.5±5.0. When the questionnaires were completed by the informants, the scores were lower for the subjects with normal cognition but higher for the MCI and dementia patients.

Sensitivity, specificity, and AUC of each instrument

ROC curves were generated to measure the effectiveness of each instrument in discriminating between the presence and absence of dementia (

Fig. 1). The AUCs of the MMSE-DS and p-KDSQ-C-II were 0.95 (95% CI=0.93–0.97) and 0.76 (95% CI=0.71–0.81), respectively, which were higher than those of the p-KDSQ-C, p-KDSQ-C-I, p-KDSQ-C-III, and p-KDSQ-C-IV. Regarding its ability to discriminate between the normal cognition and dementia groups, the p-KDSQ-C had a sensitivity of 0.62 and a specificity of 0.77 when using a cutoff score of 6. The p-KDSQ-C-II had the best combination of sensitivity and specificity, at 0.73 and 0.71, respectively, when using a cutoff score of 3. The sensitivity was lower for the p-KDSQ-C-I, p-KDSQ-C-III, and p-KDSQ-C-IV than for the p-KDSQ-C II (

Table 3). The AUC of the informant-rated KDSQ-C (i-KDSQ-C) was 0.92. The AUCs of the i-KDSQ-C-II, i-KDSQ-C-I, i-KDSQ-C-III, and i-KDSQ-C-IV were 0.92, 0.89, 0.91, and 0.91, respectively. These AUC values were higher than those of the corresponding patient-rated instruments. The i-KDSQ-C had the best combination of sensitivity and specificity, at 0.85 and 0.79, respectively, when using a cutoff score of 6. The i-KDSQ-C-II also had the best combination of sensitivity and specificity, at 0.78 and 0.93, respectively, when using a cutoff score of 6 (

Table 4).

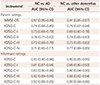

Comparison of AUCs

In assessments of the ability to discriminate between the normal cognition and dementia groups, based on patient assessments, the AUC was higher for the MMSE-DS than for all of the combinations of KDSQ-C items examined (

p<0.001) (

Table 5,

Fig. 1A). The comparisons of the p-KDSQ-C subscales revealed that the AUC was significantly higher for the p-KDSQ-C than for the p-KDSQ-C-III. The AUC also tended to be higher for the p-KDSQ-C-II than for the p-KDSQ-C, although the difference was not statistically significant. The AUC was significantly higher for the MMSE-DS than for the i-KDSQ-C-I (

p<0.001). The comparisons of the i-KDSQ-C subscales revealed that the AUC was significantly higher for the i-KDSQ-C than for the i-KDSQ-C-I and i-KDSQ-C-III (

Table 5,

Fig. 1B).

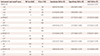

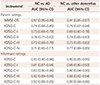

Table 6 presents the results categorized by AD and other dementias. For discriminating between patients with AD and normal cognition, based on patient assessments, the AUC was significantly higher for the MMSE-DS than for all of the KDSQ-C subscales as well as for the total KDSQ-C. Regarding the p-KDSQ-C, the AUC was higher for the p-KDSQ-CII than for the total p-KDSQ-C and all of the other subscales. For discriminating between patients with other dementias and normal cognition, based on patient assessments, the AUC was significantly higher for the MMSE-DS than for all of the KDSQ-C subscales and the total KDSQ-C. Regarding the p-KDSQ-C, the AUC was highest for the p-KDSQ-C-IV, followed by the p-KDSQ-C, p-KDSQ-C-II, and p-KDSQ-C-I (

Table 6). For discriminating between patients with AD and normal cognition, based on informant assessments, the AUCs were highest for the i-KDSQ-C and i-KDSQ-C-II, followed by the other subscales (

Table 6).

We compared the AUCs of patients and informants in order to assess dementia after adjustment for age, education level, and SGDS score (

Table 7). When comparing the completion of the questionnaires by patients and informants, the informant-rated KDSQ-C and short form of the KDSQ-C had better discriminative ability than did the corresponding patient-rated questionnaires (

p<0.001).

Correlation of instrument scores between patients and informants

The strength of the correlation between MMSE-DS and each questionnaire was quantified using Spearman's coefficient (data not shown). Negative correlations were found between the MMSE-DS and the KDSQ-C and its subscales, with positive correlations between the KDSQ-C and its subscales as well as between the subscales. For patients, the p-KDSQ-C-II showed a stronger correlation with the MMSE-DS than did the p-KDSQ-C subscales. For informants, the i-KDSQ-C and all its subscales showed strong correlations with the MMSE-DS, although the correlations were strongest for the i-KDSQ-C and i-KDSQ-C-II. The MMSE-DS was more weakly correlated with the p-KDSQ-C and its subscales than with the i-KDSQ-C. The differences in the correlations between the patient- and informant-rated scores were statistically significant (

Table 8).

DISCUSSION

Our previous study found that the KDSQ-C had good discriminability for dementia.

2 The original version of the KDSQ-C includes 15 questions that assess the 3 dimensions of memory impairment (items 1–5), other cognitive impairments including language impairments (items 6–10), and the ability to perform complex tasks in daily life (items 11–15). We divided the original version of the KDSQ-C into four subscales (I, II, III, and IV) and we compared the reliability and validity of each of these four subscales as a screening tool for cognitive dysfunction.

i-KDSQ-C-II represents two different constructs of memory and activities of daily living,

1 and had a sensitivity and specificity of 0.78 and 0.93, respectively, when using a cutoff score of 6; the corresponding values for the i-KDSQ-C were 0.85 and 0.79. The AUC of i-KDSQ-C-II was 0.92 (95% CI=0.71–0.81), which is same as that of the original i-KDSQ-C and higher than those of the i-KDSQ-C-I, i-KDSQ-C-III, and i-KDSQ-C-IV, and thus it appears to be as valid as the original i-KDSQ-C, at least in the present population. The i-KDSQ-C and i-KDSQ-C-II showed stronger correlations with the MMSE-DS. The MMSE is currently the most commonly used instrument for the primary assessment or screening of dementia in both clinical and epidemiologic case-finding applications.

1213 The results of the present study suggest that the short form of the KDSQ-C is a reliable, valid, and useful screening tool for discriminating patients with dementia while maintaining the reliability and validity of the original KDSQ-C.

The AUC of the p-KDSQ-C-II was 0.76 (95% CI=0.71–0.81), which was higher than those of the p-KDSQ-C-I, p-KDSQ-C-III, and p-KDSQ-C-IV. The AUC tended to be higher for the p-KDSQ-C-II than for the original version, but the difference was not statistically significant. Regarding the ability to discriminate between the normal cognition and dementia groups, p-KDSQ-C-II had the best combination of sensitivity and specificity, at 0.73 and 0.71, respectively, when using a cutoff score of 3. Considering that most people visiting a clinic for health checkups are not accompanied by an informant, we propose that the instrument with the greatest practical implications for the national health checkup system is the short-form p-KDSQ-C-II, since it had at least the same reliability, validity, and clinical utility as the original version of the p-KDSQ-C, and also had the best discriminability as a screening tool.

The KDSQ-C-II does not include KDSQ-C items 6–10, which assess other cognitive impairments, including language impairments, were shown to be sensitive to detecting dementia types other than AD in previous studies.

1415 The results of previous studies are supported by the present findings, where the ability to discriminate between the normal cognition and AD groups was at least as good for the KDSQ-C-II as for the original version of the KDSQ-C, while the KDSQ-C-IV had the worst ability to discriminate between the normal cognition and other-dementias groups.

When comparing the completion of the questionnaires by patients and informants, the discriminative ability was better for the informant-rated than the patient-rated short form of the KDSQ-C. This finding is in agreement previous studies showing that informant-based measurements are more useful for the early screening of cognitive changes.

1316

The findings of the present study have implications for public health. First, the i-KDSQ-C-II has excellent screening ability for dementia. Second, the p-KDSQ-C-II is also useful for screening for dementia when informants are not available. Short-form instruments are easier for patients who have cognitive impairment to complete compared to the original versions. Hence, the short form of the KDSQ-C is practical as a screening tool in a national medical checkup setting.

The present study has certain strengths: 1) it was a multicenter study that included institutions from diverse regions of the country, 2) the questionnaires were administered to paired patients and informants, and 3) MCI and dementia were diagnosed based on clinical symptoms, comprehensive neuropsychological tests, and laboratory findings, rather than just using questionnaires. However, the present study was also subject to several limitations: 1) the patients were recruited from tertiary university hospitals and dementia centers, and so they might not have been representative of the general population, 2) the group of subjects with normal cognition may have included some with subjective cognitive decline, 3) we did not apply imaging studies or comprehensive neuropsychological tests to the patients in the normal cognition group, and 4) data on the informants were not available.

In conclusion, a short form of the p-KDSQ-C and i-KDSQ-C (KDSQ-C-II) whose sensitivity, specificity, and AUCs are equal to those of the original KDSQ-C is useful as a screening tool for cognitive dysfunction. Further research on general population is needed to confirm the results.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1ROC curves. A: ROC curves for normal cognition vs. dementia for MMSE-DS, p-KDSQ-C, p-KDSQ-C-I, p-KDSQ-C-II, p-KDSQ-C-III, and p-KDSQ-C-IV. B: ROC curves for normal cognition vs. dementia for MMSE-DS, i-KDSQ-C, i-KDSQ-C-I, i-KDSQ-C-II, i-KDSQ-C-III, and i-KDSQ-C-IV. i-KDSQ-C: informant-rated KDSQ-C, KDSQ-C: Korean Dementia Screening Questionnaire-Cognition, KDSQ-C-I: items 1–5, memory domain, KDSQ-C-II: items 1–5 & 11–15, memory domain+activities of daily living, KDSQ-C-III: items 1–5 & 6–10, memory domain+other cognitive domains, KDSQ-C-IV: items 6–10 & 11–15, other cognitive domains+activities of daily living, MMSE-DS: Mini Mental State Examination-Dementia Screening, p-KDSQ-C: patient-rated KDSQ-C, ROC: receiver operating characteristic.

|

Table 1

Baseline demographic characteristics of the study subjects

Table 2

Comparison of questionnaire scores by group (patients and informants)

Table 3

Sensitivity and specificity of each instrument completed by patients when using different cutoff scores for discriminating D

Table 4

Sensitivity and specificity of each instrument completed by informants when using different cutoff scores for discriminating D

Table 5

Comparison of area under the receiver operating characteristic curves (NC vs. D) after adjustment for age, education level, and short form of the Geriatric Depression Scale score

Table 6

Comparison of AUCs (NC vs. AD or NC vs. other dementias)

Table 7

Comparison of the AUCs of patients and informants for assessing dementia after adjustment for age, education level, and SGDS score

Table 8

Results of the Fisher r-to-z transformation for the significance of differences between correlation coefficients (n=420)

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a 2017 grant from the National Health Insurance Service.

References

1. Yang DW, Cho B, Chey JY, Kim SY, Kim BS. The development and validation of Korean Dementia Screening Questionnaire (KDSQ). J Korean Neurol Assoc. 2002; 20:135–141.

2. Kim A, Kim S, Park KW, Park KH, Youn YC, Lee DW, et al. A comparative evaluation of the KDSQ-C, AD8, and SMCQ as a cognitive screening test to be used in national medical check-ups in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2019; 34:e111.

3. Christensen KJ, Multhaup KS, Nordstrom S, Voss K. A cognitive battery for dementia: development and measurement characteristics. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991; 3:168.

4. Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004; 256:183–194.

5. Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L, Wahlund LO, et al. Mild cognitive impairment--beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on mild cognitive impairment. J Intern Med. 2004; 256:240–246.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (text revision). 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: American Psychiatric Association;2000.

7. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984; 34:939–944.

9. McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O'Brien JT, Feldman H, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005; 65:1863–1872.

10. Han JW, Kim TH, Jhoo JH, Park JH, Kim JL, Ryu SH, et al. A normative study of the mini-mental state examination for dementia screening (MMSE-DS) and its short form (SMMSE-DS) in the Korean elderly. J Korean Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010; 14:27–37.

11. Bae JN, Cho MJ. Development of the Korean version of the Geriatric Depression Scale and its short form among elderly psychiatric patients. J Psychosom Res. 2004; 57:297–305.

12. Mulligan R, Mackinnon A, Jorm AF, Giannakopoulos P, Michel JP. A comparison of alternative methods of screening for dementia in clinical settings. Arch Neurol. 1996; 53:532–536.

13. Ritchie K, Fuhrer R. A comparative study of the performance of screening tests for senile dementia using receiver operating characteristics analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992; 45:627–637.

15. Folstein MF. Differential diagnosis of dementia. The clinical process. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1997; 20:45–57.

16. Morales JM, Gonzalez-Montalvo JI, Bermejo F, Del-Ser T. The screening of mild dementia with a shortened Spanish version of the “Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly”. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1995; 9:105–111.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download