INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of obesity among Korean female adolescents aged 12 to 18 increased from 7.4% in 2008 to 11.3% in 2011 [

12]. If metabolic syndrome occurs during childhood and adolescence, the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome is doubled in adulthood and diabetes is tripled [

3]. The risk factor for metabolic syndrome is the body mass index (BMI) for both adults and adolescents [

4567]. As the BMI increases, the probability of developing metabolic syndrome increases by 1.6 times in boys and 2.3 times in girls, so that adolescent girls are at higher risk for metabolic syndrome than boys [

6].

In particular, the female adolescents are likely to have a distorted perception of body type, resulting in excessive weight control [

8]. And self-body image satisfaction or body shape perception have a significant influence on eating habits [

91011121314]. Girls were more likely to put efforts into losing weight than boys [

15]. Also, the correlation between female adolescents' self-esteem and body image was higher than male adolescents' [

16]. Adolescents may be interested in weight control in ways that are not desirable, for example, because of misconceptions about their appearance or recognition by peer groups, rather than weight control for health [

1718].

Therefore, using the results of the 2010 and 2011 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), this study compared biochemical index, nutrient intakes, nutrition label use, diet-related factors and weight control behavior of Korean female adolescents at the age of 12 to 18, concerning the BMI.

DISCUSSION

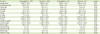

Among the study subjects, 9.7% were overweight, and about 11.7% were obese. This obesity rate was higher than 15.2% of female adolescents in Korea National Health Statistics of 2008 [

1] that indicates an increase in obesity rates in 3 years, of 2010 and 2011. In this study, the obese group was the most disadvantageous group concerning WC, systolic BP, blood triglycerides and blood HDL-cholesterol, and there were significant differences by BMI. These factors are metabolic syndrome risk factors [

2122]. In this study, the serum triglyceride in the obese group was found to be 110.2 mg/dL, which is similar to 110 mg/dL of triglyceride of the metabolic syndrome criteria of Cook et al. [

21]. Serum HDL-cholesterol level of the obese group was significantly lower than other groups (p < 0.001), as 47.9 mg/dL, but higher than 40 mg/dL of HDL-cholesterol of the metabolic syndrome criteria of Cook et al. [

21]. Criterion of Cook et al. [

21], WC and BP criteria used above the 90th percentile of gender and age, followed as below 110 mg/dL of fasting blood glucose, below 40 mg/dL of HDL-cholesterol, and above 110 mg/dL of triglyceride. Regarding criterion of Ford et al. [

22], WC, BP, triglyceride, and HDL-cholesterol criteria were the same as criterion of Cook et al. [

21], and in fasting blood glucose criterion, the 2 criteria of 110 mg/dL and 100 mg/dL were used [

22]. Regarding WC and BP, when there are 3 or more applicable criteria as above the 90th percentile of each gender and age, it can be determined as metabolic syndrome. The fasting blood glucose was higher in the obese group as 92.2 mg/dL, but it was lower than the metabolic syndrome standard, 110 mg/dL or below of Cook's criterion [

21].

According to the 2011 Korea National Health Statistics [

2], for women aged 10 to 18, the mean of fasting blood glucose was 88.2 mg/dL, the mean of total cholesterol was 162.5 mg/dL, and the mean of triglycerides was 85.2 mg/dL. However, the means for the obese group were higher as followed, 92.2 mg/dL for fasting blood glucose, 167.6 mg/dL for serum total cholesterol, and 100.2 mg/dL for serum triglycerides, respectively. Even though the biomarks of the obese group are within normal range for metabolic syndrome [

2122], their results are still higher than the normal group. Thus as earlier studies also suggest, it seems that the risk of metabolic syndrome in the obese group is higher than in the normal group.

According to the analysis of 469 male and female adolescents in the 2016 KNHANES, among the 5 diagnostic components of metabolic syndrome; WC, BP, fasting blood glucose, serum triglyceride, and HDL-cholesterol, the risk factors of metabolic syndrome for Korean adolescents are mainly reported to be abdominal obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, and low HDL-cholesterol [

4]. According to the analysis of children and teens aged 10 to 18 using the 2008 KNHANES, the obese group had significantly high prevalence in hypertension, low HDL-cholesterol, hypertriglyceridemia, and abdominal obesity [

5]. Cho [

23] reported that metabolic syndrome risk factors were more affected by BMI than body shape index in Korean adolescents. In female adolescents 12 to 18 years old, the BMI was significantly correlated with WC, serum HDL-cholesterol and triglyceride, while in female adolescents 15 to 18 years old, the BMI was significantly correlated with fasting blood glucose [

23]. In this study, the obese group with a high BMI also had significantly lower HDL-cholesterol and significantly higher serum triglyceride.

In the prior research for adolescents [

24], there was no significant difference of energy intake among the normal weight group, the obese group, and the metabolic syndrome obese group, and there was no significant difference of energy intake among the underweight group, the normal group, the overweight group, and the obese group in this study as well. And in the study by Nam and Choi [

5] of adolescents aged 10 to 18 using the 2008 KNHANES, there was no significant difference in energy and nutrient intake between the normal group and the metabolic syndrome group. Even among students aged 7 to 19, there was no significant difference in energy intake between the obese group and the normal weight group [

24].

However, the results of the nutrient intake analysis in this study suggest that it is difficult to represent the everyday eating habits of the subjects since it is a result of a one-day survey of each person. In earlier study, the ratio of underestimation of food or energy intake increased with obesity and desire for weight loss was associated with underestimate both among overweight and normal weight subjects [

25]. Considering that 80% of overweight and obese groups in this study showed they have tried fasting for weight control. So, results of this study could consider that attitudes about female adolescent's own body weight may influenced reported food or energy intake.

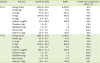

Calcium intake was 471.6 mg for those aged 12 to 14, which is 52.4% for the RNI, and 424.1 mg for those aged 15 to 18, which is 53.0% for the RNI. The similar results were found in the study by Bae [

26] using the 2010–2012 KNHANES, which showed that 473.7 mg of calcium intake for girls aged 12 to 14 and 432.1 mg for girls aged 15 to 18, that are similar to the results of this study, and it suggests that calcium is the most deficient nutrient by RNI. The results revealed that the prevalence of calcium deficiency is high in female adolescents.

Eating breakfast, experience of nutrition education, recognition of nutrition label, use of dietary supplements over the past year, and dietary circumstance were not significantly different in relation to BMI. There was no significant difference in the awareness of ‘nutrition label,’ but there was a significant difference in ‘use of nutrition label’ (p < 0.05), as the use rate of nutrition label in the normal, the overweight and the obese groups were 1.5–1.7 times higher than the underweight group. This result suggests that it is related to the higher rates of answers for efforts to lose weight in the ‘weight control over the past year’ question in the overweight and the obese groups, compared to the lower rates of the answers in the underweight and the normal groups. The recognition rate for nutrition label was more than 90%, but it was found to be less than 50% for nutrition label utilization rate, and the experience rate of nutrition education was found to be less than 15% for all subjects. Overall, it is necessary to strengthen nutrition education.

Overweight adolescents were regarded as obese weight, and normal adolescents were considered as overweight, the overestimation of body weight may induce the motivation to lose more weight. In this study, 25.3% of the normal group thought they are obese, and 75.3% of female adolescents have tried to lose weight in the normal group, among those who had experience with weight control. Also, in the underweight group, when they put efforts for weight control, the ‘weight loss efforts’ was 18.9%. In previous research, the subjective body recognitions were worse for female students than male students, as they perceived themselves as obese even though they aren't [

15]. And Choi et al. [

8] reported that, for the rates that recognizing oneself as obese even if he or she is not, are higher in the female underweight group than the male one, and it was the same for the normal groups as well. Choi et al. [

8] also showed that there was a higher abnormal recognitions of subjective body image in the normal groups, which is consistent with the results of this study. In previous research, perceptions of overweight and attempts to lose weight were highest in the group of university students in Asian countries where body weights are generally low. And more women than men felt they were overweight [

14]. According to Bellisle et al. [

27], who studied 16,486 university students in 21 countries, in spite of the low BMI, many students perceived themselves as overweight, especially women. Trying to lose weight (44% of women, 17% of men) and dieting (14% in women, 3% in men) were not uncommon [

27]. Among the weight control methods, fasting was the highest as 80% in all groups, compared to exercise and reducing diet.

Female adolescents' self-perceptions of body weight can be influenced by their peers who misperceive their body weight, especially with the overestimation of their normal weight at school. Therefore, it implies that not only education on proper subjective body image perception, but also education on proper weight control methods and nutrition label are necessary for the overall health care of people.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download