Abstract

Figures and Tables

Figure 4

Digital simulations. A, Virtual set-up model for extraction of maxillary first premolars and mandibular incisor. B, Superimposition of the findings before and after simulation. C, Superimposition of three-dimensional crowns on lateral cephalogram (lateral head film aligned to the midsagittal plane of models) (Motion View Software, LLC).

Figure 5

Extraction of maxillary first premolars and mandibular incisor. A, Possible equilibration map. B, Expected tooth movement (Motion View Software, LLC).

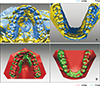

Figure 6

Digital simulations. A, Virtual set-up model for extraction of maxillary first premolars. B, Superimposition of findings before and after simulation. C, Superimposition of three-dimensional crowns on lateral cephalogram (lateral head film aligned to midsagittal plane of models).

Figure 7

Extraction of maxillary first premolars. A, Possible equilibration map. B, Interproximal reduction to accommodate occlusion. C, Expected tooth movement.

Figure 9

Full-arch distalization of the maxillary arch (after 12 months of distalization). During the distalization of the maxillary arch, Class III elastics were engaged on the right side to establish Class I relationship and triangular elastics from the upper canine to lower canine and the first premolar on the left side.

Figure 11

Intraoral photographs showing the treatment progress (after 21 months of treatment). The lingual buttons attached to the maxillary second molars were engaged to the palatal plate to express lingual crown torque along with the torque in the 0.019 × 0.025-inch stainless steel wire.

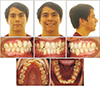

Figure 16

Cone-beam computed tomography superimposition before and after maxillary total arch distalization (before, gray; after, yellow).

Figure 17

Superimpositions before and after cone-beam computed tomography and digital model superimposition (Orapix system; Cenos Co., Ltd.). A, Cone-beam computed tomography images (blue, initial; yellow, final). B, Digital model images (red, initial; green, final).

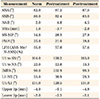

Table 1

Cephalometric measurements

SNA, Angle between anterior cranial base (SN) and point A; SNB, angle between SN and point B; ANB, angle between lines NA and NB; Wits, distance between point A and point B on occlusal plane; SN-MP, angle between SN and mandibular plane; FMA, angle between FH plane and mandibular plane; LFH, lower facial height; ANS, anterior nasal spine; Me, menton; N, nasion; U1 to SN, angle between long axis of upper incisor and SN; U1 to NA, angle between long axis of upper incisor and nasion-point A line; IMPA, mandibular incisor angle to mandibular plane; L1-NB, angle between long axis of lower incisor and nasion-point B line; U1/L1, angle between long axis of upper and lower incisors; Upper lip, distance between upper lip and E-line; Lower lip, distance between lower lip and E-line.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download