A 59-year-old woman attended a private clinic because of a productive cough two months before visiting our hospital. She was diagnosed with bacterial pneumonia and was treated with antibiotics for two weeks. However, serial chest radiographs indicated a gradual increase in the extent of pneumonic consolidation. Chest radiography performed upon the patient's visit to our hospital indicated an ill-defined, increased opacity in the left upper lung field (Fig. 1A). Chest computed tomography (CT) revealed air space consolidation and ground glass opacity (GGO) in the left upper lobe (LUL) bronchus; LUL bronchus wall thickening and enhancement were also observed (Fig. 1B). Subsequently, bronchoscopy revealed total luminal obstruction of the anterior segment of the upper division of the LUL bronchus, with an endobronchial mass-like lesion (Fig. 1C). Histopathologic examination of a mucosal tissue biopsy revealed significant accumulation of eosinophils and lymphocytes in the bronchial epithelium (Fig. 1D). There was no evidence of carcinoma in the biopsy specimen, as indicated by the lack of CD56 staining (Fig. 1E). Next, we performed bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) of the LUL bronchus; analysis of the BAL fluid revealed that eosinophils constituted 35% of the cells present. Bacteria or fungi were not identified and results of the cytology of the bronchoscopic specimens were negative. The smear and culture tests for acid-fast bacilli were negative, as was the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Peripheral eosinophilia (white blood cell count, 12,300/mm3, of which 12.6% were eosinophils) and the elevated serum IgE (1748 IU/mL) were revealed in a blood test. Clinical and laboratory findings showed no indication of vasculitis. With the exclusion of parasite-associated disease and other medical conditions, such as vasculitis, that can cause eosinophilia, chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP) was diagnosed, and the patient commenced steroid treatment using intravenous methylprednisolone (one mg/kg/day). One day after the start of steroid therapy, the patient's cough had subsided and their peripheral eosinophil count normalized, declining to a level of 0.1%. After one week of treatment, their chest radiograph showed a marked decrease in the extent of LUL consolidation (Fig. 2A). We repeated the chest CT and bronchoscopy two weeks after steroid therapy. The post-treated chest CT indicated a decrease in the extent of air space consolidation and GGO in the LUL and an improvement in endobronchial narrowing of the LUL lobar bronchus (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, post-treatment bronchoscopy revealed the bronchial obstruction had completely receded; together with the complete luminal opening and the disappearance of the abnormal mass-like lesion (Fig. 2C). The patient has been closely followed up on in the outpatient department of our hospital for one month and has had no recurrence of respiratory symptoms or visible abnormalities on their chest radiographs. Bronchial involvement of CEP is rare.1 Kim et al.2 reported bronchial involvement CEP, the difference from our report is that mass-like lesion was presented in imaging study such as, CT or bronchoscopy, which could be confused with bronchogenic malignancy. Although the patient had peripheral blood eosinophilia at their initial presentation, neither the radiologist nor the pulmonologist considered this when assessing the patient's chest CT.

Figures and Tables

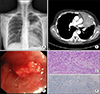

FIG. 1

Chest X-ray indicates an ill-defined increased opacity at left upper lung (LUL) (A). Chest CT was revealed that air space consolidation and ground-glass opacity (GGO) at LUL. Furthermore, LUL lobar bronchus wall thickening and obliteration can be seen (B). Bronchoscopy revealed luminal impaction of the anterior segment of the LUL upper-division due to a mass forming lesion (C). Biopsy tissue sections featured diffuse eosinophilic infiltration (D). The biopsy sections were negative for CD56 staining (E). All biopsy sections underwent hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, and photographs were taken at a magnification of 400×.

FIG. 2

Follow up chest X-ray showed a marked decrease in the extent of consolidation in the LUL (A). The post-treatment chest CT indicated a decrease in the extent of air space consolidation and GGO in the LUL and reduction of the endobronchial narrowing of the LUL lobar bronchus (B). Follow up bronchoscopy showed complete resolution of the bronchial obstruction, which was associated with the total luminal opening (C).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download