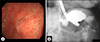

A 77-year-old man presented to the authors' department with a 6-day history of nausea and vomiting. Two months previously, the patient underwent uneventful percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) due to sarcopenia after a traumatic spinal cord injury (Fig. 1A). Vital signs were normal, and the abdomen was soft with hypoactive bowel sounds. Laboratory results were unremarkable. When the gastrostomy tube was opened, no outflow could be observed; however, a fecal odor from the tube was observed. Abdominal radiography showed no distention of bowel loops. Computed tomography (CT) revealed gastrocolic fistula and migration of the gastrostomy tube into the transverse colon (Fig. 1B). Colonoscopy confirmed the fistula (Fig. 1C); thus, the colonic side opening was endoscopically closed using over-the-scope-clip (OTSC) system (traumatic type, Olympus, Japan). In addition, the patient underwent successful removal of the migrated tube and closure of the colonic orifice of the colocutaneous fistula with the above-mentioned OTSC system (Fig. 1D). Two days later, gastroscopy and contrast radiography using diatrizoate meglumine anddiatrizoate sodium (gastrografin) confirmed the closure of the fistula on the gastric mucosa (Fig. 2). The patient started oral intake and was discharged to a nursing home.

Gastrocolocutaneous fistula is a rare complication of PEG. This iatrogenic fistula results from the interposition of the colon between the anterior abdominal wall and the stomach. Risk factors for this complication include megacolon, subphrenic transposition of the colon, abnormal posture and spinal deformity,1 previous abdominal surgery,1 or overinflation of the stomach during PEG.2 Although the typical symptoms are sudden onset of diarrhea and feculent vomiting, most patients are asymptomatic until the gastrostomy tube migrates into the colon (such as the time of tube replacement). On the other hand, since life-threatening peritonitis may occur, the prevention, early diagnosis, and treatment are important.

For the prevention, the following methods are recommended: (1) trans-illumination and finger pressure as a guide to placement of the puncture site; (2) a needle aspiration test (using a syringe, puncture under continuous aspiration towards the air-filled stomach); or (3) perpendicular puncture of the abdominal wall.34 Colonoscopy-assisted PEG is also useful to avoid this complication.5 In our case, trans-illumination prior to gastric puncture could not be achieved, and the gastrostomy tube was not inserted vertically to the abdominal wall.

Gastrocolocutaneous fistula is diagnosed by fistulagraphy (injection of gastrografin through the gastrostomy tube), CT, and colonoscopy. In our case, an interesting etiology was considered. First, accidental removal of the gastrostomy tube was excluded by detailed inquiries. Second, the patient had a history of chronic constipation due to neurogenic bowel dysfunction, which had been managed with laxatives leading to melanosis coli (Fig. 1C). Therefore, the dilated colon may cause gastrostomy tube migration secondary to buried bumper syndrome.

There is limited information available on the management of gastrocolocutaneous fistula. While most patients present a benign clinical course with fistula closing spontaneously after the tube removal, the closure can be disturbed by delayed wound healing and leakage of gastric juice through the fistula. If the fistula cannot close spontaneously, endoscopic closure is an effective and less invasive approach.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download