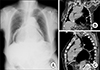

An 83-old woman with an otherwise unremarkable medical history, reported retrosternal discomfort and underwent upper endoscopy, revealing a large diverticulum in the middle thoracic section of the esophagus. Sudden hemorrhage originating from the diverticulum interrupted further procedure and the bleeding was successfully stabilized by endoscopic intervention. An hour later, the patient started complaining about significant chest pain. Her vital signs were stable. An urgent chest x-ray (CXR) revealed a wide radiolucent area within the right and left paracardiac region which was highly suggestive of pneumomediastinum (Fig. 1A).

Onset of symptoms such as chest/epigstric pain, vomiting, dyspnea, dysphagia, haematemesis or subcutaneous emphysema after an upper endoscopy lead to the suspicion of esophageal perforation (EP). However, current data demonstrates that the initial diagnosis is wrong in one out of two cases.1 The risk of EP during diagnostic endoscopy ranges from 0.03 to 0.11%, and is more common in the elderly population (>60 years), where coexisting esophageal diverticula further increases that risk.2 The clinical presentation of EP is highly variable and depends upon the location (cervical, thoracic, abdominal) and the time interval until the diagnosis. In the case of thoracic EP, the standard CXR, thoracic multidetector computed tomography (MDCT), esogastroduodenal follow trough, and even esophageal endoscopy with precaution of enlargement of the transmural opening are helpful tools to establish the diagnosis. In thoracic EP, CXR may be abnormal in up to 90% of cases, demonstrating pleural effusion, pneumothorax or hydropneumothorax, and pneumoperitoneum.3 However, at least a one hour delay after perforation is necessary to demonstrate a development of pneumomediastinum.3 Thoracic MDCT is the procedure of choice due to its high sensitivity rates (92–100%) and it being 10 times as sensitive as CXR in detecting pneumomediastinum.45 Indeed, MDCT was performed in our case and showed a large air-filled cavity which shifted the cardiac structures forward. Both the gastroesophageal junction and a part of the stomach were situated above the diaphragm, in the mediastinum, impinging on the posterior cardiac structures and forming a large hiatal hernia (Fig. 1B, C). The patient remained stable and three days later was discharged from the hospital on proton pump inhibitors. The true incidence of massive hiatal hernias remains unclear as it varies according to the definition thereof; however, paraesophageal hernias account for 5–15% of all hiatal hernias and are more commonly seen in older population.6

In conclusion, chest pain after upper endoscopy may result from massive air insufflation into a preexisting hiatal hernia mimicking an oesophageal perforation. Prompt and timely management is of the utmost importance in order to define the circumstances of clinical signs and avoid life-threatening complications.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Griffiths EA, Yap N, Poulter J, Hendrickse MT, Khurshid M. Thirty-four cases of esophageal perforation: the experience of a district general hospital in the UK. Dis Esophagus. 2009; 22:616–625.

2. Chirica M, Champault A, Dray X, Sulpice L, Munoz-Bongrand N, Sarfati E, et al. Esophageal perforations. J Visc Surg. 2010; 147:e117–e128.

3. Brinster CJ, Singhal S, Lee L, Marshall MB, Kaiser LR, Kucharczuk JC. Evolving options in the management of esophageal perforation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004; 77:1475–1483.

4. de Lutio di Castelguidone E, Merola S, Pinto A, Raissaki M, Gagliardi N, Romano L. Esophageal injuries: spectrum of multidetector row CT findings. Eur J Radiol. 2006; 59:344–348.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download