INTRODUCTION

According to the ‘2014 Korean Interns & Residents Survey,’ the average weekly working time of trainee doctors was 93 hours.

1 ‘Act on the improvement of training conditions and status of medical residents’ was officially enacted on December 22, 2015, and was announced to the public through the ‘Statutes of the Republic of Korea.’

2 Its main proposal was limiting resident work hours to 88 hours per week, including 8 hours for education purposes.

3 To compensate for the residents' reduced working hours, hospitalist, physician assistant and nurse practitioner systems have been discussed. However, because of no established legal status (physician assistant and nurse practitioner),

4 shortages of candidates (hospitalist) and the specialty of critical care, the application of these systems is not easy in the intensive care units (ICUs) of Korea.

Medical resources such as medical staff and equipment are concentrated in ICUs. Among the medical staff, medical residents are essentially needed to operate the ICU. However, there are not enough medical residents in reality, especially at regional hospitals.

5 In addition, after restriction of residents' working hours according to the resident law, it has been more requested that substitutes for medical residents be placed in the ICU. Because of these reasons, Korean regional academic hospitals may be likely to face running ICUs without residents in the near future.

If there are no alternatives, an intensivist has no choice but to become actively involved and endure overwork from managing critically ill patients in the ICU. We compared the outcomes of two ICUs in a regional academic hospital: one was operated by a critical care specialist with residents, and the other was operated by a critical care specialist without residents. The primary outcome was overall ICU mortality. The secondary outcomes were length of stay in the ICU, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT), cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and advanced care planning decisions such as physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST) before death.

METHODS

Study design and subjects

We performed a retrospective observational study of internal medicine patients older than 18 years who were admitted to two ICUs (emergency ICU [EICU] and medical ICU [MICU]) from general wards at Ulsan University Hospital, Korea, between September 2017 and February 2019. Controlling for the potential confounding effects, we excluded cardiology patients and patients who transferred to other ICUs because ICU outcomes might be greatly influenced by coronary interventions of attending physicians or management by other ICU staff. If a patient was repeatedly admitted to the ICU during the study period, we collected the data for the first ICU admission as the index admission.

Two ICU settings, medical staff and equipment

Critically ill patients from the emergency room were usually admitted to the EICU, and those from general wards were admitted to the MICU first. The EICU had 20 beds with 7 isolated rooms, and the MICU had 12 beds with 4 isolated rooms. If there were not enough beds in the MICU, critically ill patients from general wards were admitted to the EICU, and if there were not enough beds in the EICU, critically ill patients from the emergency room were admitted to the MICU. Although ICU residents affected the patients' ICU admission, ICU intensivists finally decided the patients' ICU admission in both ICUs. Two ICUs shared ICU equipment, such as a video laryngoscope, ECMO, CRRT, and ultrasound machines. The nurse staffing grade (based on the nurse-to-bed ratio) of both ICUs was the same, namely, 0.43.

6 Patients in both ICUs were comanaged by intensivists (high-intensity staffing, i.e., mandatory involvement of intensivists as primary physicians or consultants during the day time) and attending physicians (transitional units).

78

Two intensivist physicians and three residents all belonged to the department of internal medicine, and they administered treatment to internal medicine patients in the two ICUs. The EICU was operated by one intensivist with three residents (one was a 2nd-year resident and two were 3rd-year residents). In the EICU, the intensivist and two residents treated patients during the daytime, and the other resident worked at night. Three residents worked in rotation (duty schedule: 6:00 PM–next day 1:00 PM, 7:00 AM–7:00 PM, and off).

The MICU was operated by only the other intensivist without residents and he stayed in MICU during the daytime. ICU nurses directly reported the patients' problems to the MICU intensivist. The MICU intensivist primarily evaluated the patients' condition and managed the patients' problems (drug prescription, medical recording, endotracheal intubation, insertion of a central line catheter and pig tail catheter, etc.) similarly to the residents. One nurse assisted with the intensivist physician's work while doing her own nursing practice in the daytime. She entered prescriptions into the Order Communication System as the intensivist's deputy according to the direction of the MICU intensivist (the prescription would be approved after the MICU intensivist's confirmation). During the nighttime, eight internal medicine specialists (including two intensivists) and one 3rd-year resident were on duty in rotation (night duty time: 6:30 PM–next day 7:30 AM).

One of two intensivists was an internal medicine specialist and completed the fellowship programs of both pulmonology and critical care medicine. The other was also an internal medicine specialist and had certifications in both the pulmonology and critical care medicine subspecialties. Two intensivists worked by taking turns in each ICU every 3 months (

Fig. 1). The duration of the two intensivists' shift was from 7:30 AM to 6:30 PM, however, they were also called and treated patients in emergency situations occurring during the night.

| Fig. 1

Distribution of the study patients according to type of ICU.

ICU = intensive care unit, EICU = emergency intensive care unit, MICU = medical intensive care unit.

|

One experienced pharmacist had rounded with intensivists five times a week and nutrition support team (consisted of nurse, pharmacist, nutritionist and each ICU intensivist) had rounded one or two times a week in both ICUs during the study period. In addition, there were no fellows in both ICUs during the study periods.

Data collection

Clinical and laboratory variables were collected from the clinical data warehouse platform in conjunction with the electronic medical records at the Ulsan University Hospital (Ulsan University Hospital Information of Clinical Ecosystem [uICE]). One of the study authors specializing in pulmonary and critical care medicine reviewed all the patient data obtained from the uICE and addressed any errors by rechecking the patient data directly for accuracy. We defined the patients with immunosuppression as those who underwent solid organ transplantation or were treated with chemotherapeutic agents, steroids and/or immunosuppressive drugs within 6 months of ICU admission. The Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score was calculated by using the worst variable within the first 24 hours of ICU admission. We defined POLST as the acquisition of consent for do-not-resuscitate orders or the determination to terminate treatment according to the ‘Act on Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment for Patients in Hospice and Palliative Care or at the End of Life.’

Rapid response system

Critically ill patients in general wards have been co-managed by a rapid response system with an electronic medical record-based screening program and a professional group (one medical specialist and two nurses) since June 2, 2014.

9 The rapid response system was operated during the day time (8:30 AM–5:30 PM) in the study period.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as the median (interquartile range) or mean ± standard deviation, depending on the distribution and were compared using the independent t-test. Categorical variables are expressed as numbers (in percentages) and were compared using the χ2 test.

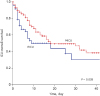

The survival rates for both ICU patients were calculated by using the Kaplan-Meier curve and compared via the log rank test. We performed a multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression analysis to analyze the overall ICU mortality between the both types of ICU patients adjusted by using age, gender and variables with P value < 0.1 in the univariate Cox proportional hazard regression analysis. To compare the secondary outcomes, we conducted a multiple logistic and linear regression analysis adjusted by using age, gender and variables with P value < 0.1 in a univariate regression analysis. Additionally, we checked the variance inflation factor, which was used to detect multicollinearity, before the multivariate analysis. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 24.00 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Ulsan University Hospital (IRB No. 2019-05-025). We did not seek informed consent from the patients, as the study was retrospective in design and all the data were anonymized.

DISCUSSION

Our study results suggested that intensivists' direct management without residents might be associated with a lower ICU mortality than that resulting from ICU residents' management under intensivist supervision at academic ICUs. In addition, intensivists' direct management was also found to be associated with lower CRRT application and CPR in the ICU and more advanced care planning decisions before death. One study suggested that the absence of emergency medicine residents did not affect the activity and quality of patient management in the academic emergency department.

10 Another study reported that direct staff physician (instead of resident) management resulted in fewer laboratory tests ordered, fewer radiographs ordered, and shorter lengths of stays in the emergency department.

11 However, these studies evaluated the effect of staff physician's direct management without residents in non-critically ill patients and over a short period of time, and there were no data evaluating the ICU outcomes according to intensivist physician's direct management at academic ICUs. Our present study is, to our knowledge, the first to assess such outcomes in the ICU over a relatively long period.

This investigation was performed with an intensivist crossover study design between the two ICUs. We initially did not intend to conceive this study design. Between the two ICUs, there was a higher workload associated with the absence of residents in the MICU, and two intensivists agreed to work at each ICU alternatively after a mutual consultation. Through this arrangement, we minimized the difference between the two intensivists in ability that might have influenced the ICU outcomes, and consequentially, this design is a strength of our study.

ICU outcomes are influenced by many factors, such as ICU staff, equipment, ICU operation methods, and so on. Among these factors, the ICU staff is composed of residents, fellows, intensivists, nurses, respiratory care practitioners, pharmacists and nutritionists.

7 In most academic hospitals, ICUs are usually operated by residents under the supervision of a fellow, attending staff or intensivist. Although one large study reported that patients managed by intensivists had a higher mortality than patients who were not,

12 most studies have suggested that high-intensity critical care specialist staffing is associated with improved ICU outcomes.

813141516 Furthermore, some authors have asserted that a 24-hour intensivist presence in the ICU would improve diagnostic and therapeutic efficiency, particularly for high-risk patients.

171819

Considering the above studies and our results, ICU intensivist staffing might be associated with favorable ICU outcomes, and more active direct intervention of an ICU intensivist without residents was associated with much better ICU outcomes than indirect management through residents. We thought the better MICU outcomes resulted from the intensivists' specialty, rapid decision making, appropriate management, skilled procedures and responsibility, although the doctor-to-bed ratio of the EICU was higher than that of the MICU during the daytime (3:20 vs. 1:12) in our study. In addition, direct management by an intensivist might lead to patient, family and caregiver satisfaction by providing high-quality care in the ICU.

20

However, there are several practical problems associated with an intensivist's direct management of the ICU. First, the number of intensivists is not enough to cover all ICUs. There has continued to be a nationwide shortage of intensivists. We expect the shortage of intensivist to continue in the future because the population is aging, which will lead to an increase in the burden of acute and chronic illnesses and the need for critical care services.

2122 It is therefore necessary to provide institutional strategies for increasing the intensivist volume and decreasing prolonged, ineffective and harmful critical care for effective intensivist care.

2223 Second, recruitment of intensivists is difficult because of the difficult working conditions, such as overwork, night duties, conflict with colleagues and continual exposure to stressful situations.

24 In our study, intensivists were also overworked during the MICU duty period. Their average weekly work time was approximately 90 hours (day duty time: 55 hours/week [11 hours/day × 5 days/week]; shift overlap & preview times: 5 hours/week [0.5 hours/day × 2 × 5 days/week]; night duty time: approximately 20 hours/week [intensivist’s night duty was every 5–6 days, weekday night duty time: 13 hours and weekend night duty time: 24 hours], emergency call, research, education of trainees and so on). Specific interventions to prevent or treat burnout syndromes are needed, such as limiting the maximum number of days worked consecutively, actively increasing the number of physician assistants, suitable economic rewards, stress reduction training, relaxation techniques, and other measures.

2224 Third, there were concerns about rising medical costs because of the substitution of intensivists for residents. Considering the public benefits of medical treatment and the relationship of the health insurance system, we thought that financial and social policy support was required from not only the hospital itself but also the government to solve this problem.

2526

Our study had several limitations. First, it was a retrospective observational study. Selection bias might have occurred, and some of the patients' data were incomplete. However, we tried to minimize the differences between the two ICUs by carefully selecting and enrolling the study patients. Second, our investigation was conducted as an outcome evaluation of ICU patients from general wards at a single tertiary referral center, and although we recruited as many patients as possible, the sample size was not large enough. Selection bias cannot be excluded, and larger-scale multicenter studies are required to obtain more accurate and reliable results. Third, the two ICUs had different ICU bed capacities (EICU vs. MICU, 20 beds vs. 12 beds, respectively), main medical teams during the day (1 intensivist & 2 residents vs. 1 intensivist, respectively), and patient compositions (mainly from the emergency room vs. general wards, respectively). Consequently, the study results should be interpreted with caution. Fourth, our study patients had a high overall ICU mortality, which we believe is because of the high frequency of poor prognosis factors, such as malignancies, immunosuppression, and high APACHE II scores. The study protocol, which stipulated that only patients transferred to the ICU because of management failure from general wards were enrolled, is also likely to have contributed to the high ICU mortality. Fifth, our study revealed the superiority of intensivist’s direct management to ICU patients in terms of ICU outcomes. However, we could not provide solutions for the intensivists' direct management-related problems. Further financial and social policy support is required, and our retrospective data on direct management by intensivists may represent a major starting point for a randomized controlled study.

Intensivists play a central role in critical care medicine. In our study, intensivists' direct management without residents was associated with significantly better overall ICU mortality, CRRT application, CPR, and advance care planning decisions before death than indirect management through medical residents. Our findings suggest that larger prospective randomized trials on intensivists' direct management of ICU patients are warranted. Furthermore, we believe that additional approaches to establishing the proper environment for active work by intensivists are needed.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download