Abstract

Background

Due to occupational exposure, healthcare workers (HCW) face an increased risk of tuberculosis (TB) infection. This study was conducted to assess the prevalence and risk factors of latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI), and to estimate the cumulative risk of active TB among HCWs.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study among HCWs in Ajou university medical center. A standard questionnaire was used for data collection, and LTBI was detected using the Interferon gamma-release assay (IGRA). The biographical information was collected from the electronic database. A computerized algorithm was used to evaluate the predicted cumulative risk of active TB in HCWs with LTBI.

Results

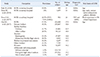

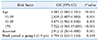

Of a total of 1,407 HCWs, a positive IGRA result was detected in 138 HCWs. The prevalence of LTBI in HCWs was found to be 9.8% [95% confidence interval (CI) 8.2-11.4]. It was observed that the prevalence of LTBI increased with age (P value<0.001). However, it was also observed that duration of the working periods in a TB-related department was not associated with LTBI (P value=0.369). According to the multivariate analysis, an increased risk of LTBI was observed among participants aged ≥ 50 years [odds ratio (OR) 7.522, 95% CI 3.56-15.89] and nursing assistants (OR 2.912, 95% CI 1.283-6.608). The median cumulative risk of active TB with LTBI was estimated to be 4.31% [interquartile range (IQR) 3.43-5.29], and 4.41% (IQR 3.14-5.29) in HCWs with and without work experience in TB-related department, respectively. No significant difference was observed between two groups (P value=0.715).

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Flow chart of the study.Abbreviations: See Table 1.

|

| Fig. 7Cumulative risk of active tuberculosis in healthcare workers with latent tuberculosis infection by age group. |

Table 1

Comparison of studies for latent tuberculosis infection prevalence among healthcare workers and other groups in South Korea

References

1. WHO. Global tuberculosis report 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization;2018.

2. Kim JH. Achievements in and challenges of tuberculosis control in South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015; 21:1913–1920.

3. Cho KS, Park WS, Jeong HR, Kim MJ, Park SJ, Park AY, et al. Prevalence of latent tuberculosis infection at congregated settings in the Republic of Korea, 2017. Division of TB & HIV Control, Center for Disease Prevention, KCDC;2017.

4. Getahun H, Matteelli A, Abubakar I, Aziz MA, Baddeley A, Barreira D, et al. Management of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection: WHO guidelines for low tuberculosis burden countries. Eur Respir J. 2015; 46:1563–1576.

5. Jagger A, Reiter-Karam S, Hamada Y, Getahun H. National policies on the management of latent tuberculosis infection: review of 98 countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2018; 96:173–184F.

6. Park JS. The prevalence and risk factors of latent tuberculosis infection among health care workers working in a tertiary hospital in South Korea. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2018; 81:274–280.

7. Yeon JH, Seong H, Hur H, Park Y, Kim YA, Park YS, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of latent tuberculosis among Korean healthcare workers using whole-blood interferon-γ release assay. Sci Rep. 2018; 8:10113.

8. Yoon CG, Oh SY, Lee JB, Kim MH, Seo Y, Yang J, et al. Occupational risk of latent tuberculosis infection in health workers of 14 military hospitals. J Korean Med Sci. 2017; 32:1251–1257.

9. Lee KJ, Kang YA, Kim YM, Cho SN, Moon JW, Park MS, et al. Screening for latent tuberculosis infection in South Korean healthcare workers using a tuberculin skin test and whole blood interferon-gamma assay. Scand J Infect Dis. 2010; 42:672–678.

10. Lee SH. Diagnosis and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2015; 78:56–63.

11. Menzies D, Gardiner G, Farhat M, Greenaway C, Pai M. Thinking in three dimensions: a web-based algorithm to aid the interpretation of tuberculin skin test results. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008; 12:498–505.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download