This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Fractures of the styloid process of the temporal bone may occur with or without an obvious relation to trauma. The incidence of either isolated styloid process fracture or in combination with mandibular fractures is rare, and such occurrences are often misdiagnosed or neglected. A fractured styloid when displaced may impinge on adjacent vital structures, leading to neurological or vascular symptoms that vary according to the anatomical structure compressed. Styloid process fractures associated with atlas/C1 fractures have also been rarely reported in the literature. In this review of literature, the majority of patients was treated conservatively, as few demonstrated the necessity of surgical intervention. There is a definitive need for a protocol to recognize and classify styloid fractures to plan for further treatment. The aim of this review was to achieve a comprehensive understanding of all types of styloid fractures, determine the clinical severity of symptoms, and to consider management and prognosis. In addition, a new classification of cervico-stylo-mandibular fractures is proposed based on important evidence in the literature regarding clinical and radiographic factors that might influence the treatment and prognosis of such fractures.

Go to :

Keywords: Styloid process fractures, Cervico-stylo-mandibular fractures, Classification

I. Introduction

Though the actual incidence of styloid process (SP) fracture is high, failure to diagnose results in a smaller number of reported cases

1. Incidence of styloid fracture concomitant with mandibular fractures is infrequent in occurrence

2345; due to the high variability of vague symptoms on presentation, such patients rarely report to a maxillofacial surgical unit

678. The role of a maxillofacial surgeon is to prevent misdiagnosis or mismanagement of patients with SP fracture and to prevent long-term complications of traumatic styloid syndrome through appropriate treatment and post-operative review

78. There is extremely sparse discussion on management of such fractures occurring along with mandibular fractures

9. Rarely, these styloid fractures may also be associated with fracture of the atlas

1011. The clinical dilemma regarding management of these cervico-stylo-mandibular fractures must be addressed by establishing a definitive treatment algorithm.

Recently, a few surgeons have focused on classification based on radiological imaging in temporal SP fractures

1213. A validated, comprehensive, and structured classification of cervico-stylo-mandibular fractures has not been proposed until now. An injury severity classification system would help surgeons in making decisions about the most appropriate treatment modalities and in including prognostic factors for clinically relevant patient outcomes

14. The purpose of this study is to produce a clinical grading system based on the severity of symptoms by establishing an injury severity score grading system, taking into account management and prognosis. Currently, there is no efficient reproducible classification system that provides elements for treatment and prognosis. This study also aims to propose a new classification for cervico-stylo-mandibular fractures following a critical review of the literature.

Go to :

II. Review of Literature

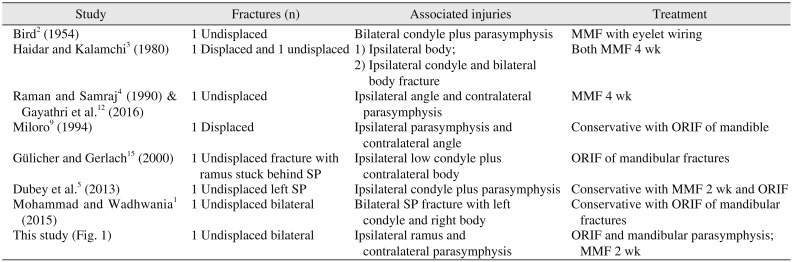

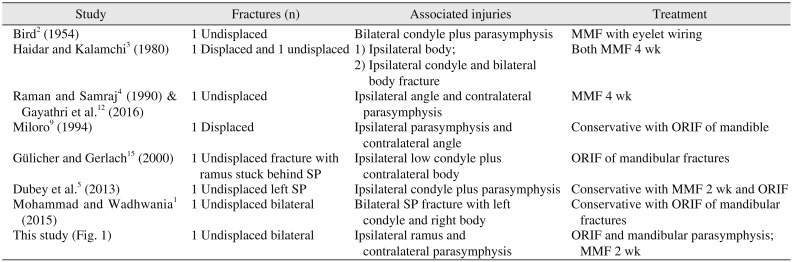

A total of 30 case reports of SP fracture was critically reviewed from the existing literature. Among these, 18 involve isolated styloid fractures, 9 focus on stylo-mandibular fractures, and 3 involve fractures associated with the atlas/C1. Isolated styloid fractures were excluded from the review. (

Table 1)

Table 1

Stylo-mandibular fractures reported in the literature

|

Study |

Fractures (n) |

Associated injuries |

Treatment |

|

Bird2 (1954) |

1 Undisplaced |

Bilateral condyle plus parasymphysis |

MMF with eyelet wiring |

|

Haidar and Kalamchi3 (1980) |

1 Displaced and 1 undisplaced |

1) Ipsilateral body; |

Both MMF 4 wk |

|

2) Ipsilateral condyle and bilateral body fracture |

|

Raman and Samraj4(1990) & Gayathri et al.12(2016) |

1 Undisplaced |

Ipsilateral angle and contralateral parasymphysis |

MMF 4 wk |

|

Miloro9(1994) |

1 Displaced |

Ipsilateral parasymphysis and contralateral angle |

Conservative with ORIF of mandible |

|

Gülicher and Gerlach15(2000) |

1 Undisplaced fracture with ramus stuck behind SP |

Ipsilateral low condyle plus contralateral body |

ORIF of mandibular fractures |

|

Dubey et al.5(2013) |

1 Undisplaced left SP |

Ipsilateral condyle plus parasymphysis |

Conservative with MMF 2 wk and ORIF |

|

Mohammad and Wadhwania1(2015) |

1 Undisplaced bilateral |

Bilateral SP fracture with left condyle and right body |

Conservative with ORIF of mandibular fractures |

|

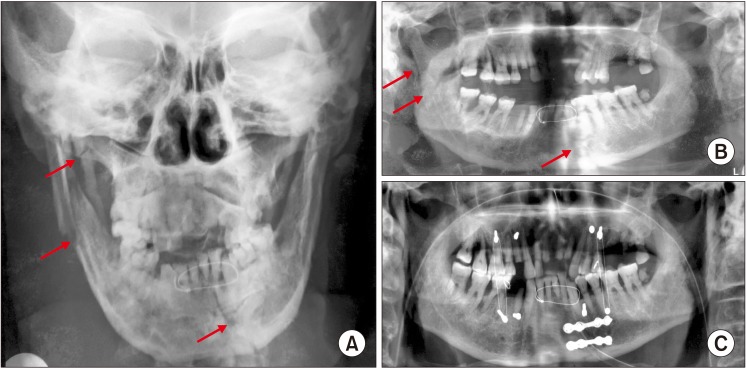

This study (Fig. 1) |

1 Undisplaced bilateral |

Ipsilateral ramus and contralateral parasymphysis |

ORIF and mandibular parasymphysis; MMF 2 wk |

Almost all the reported cases of stylo-mandibular fractures were managed conservatively by open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) surgery with maxillomandibular fixation (MMF) for 2 to 4 weeks. Even in the case reported at our unit, we followed a closed reduction and MMF for 2 weeks. (

Table 1,

Fig. 1) The work of Gülicher and Gerlach

15 reports a case of mandibular fracture that failed to be reduced due to fracture of the SP, which suggests the need for surgical removal of the fractured SP. Based on the evidence in the literature regarding clinical and radiographic factors, five parameters are considered to establish a severity score grading system.

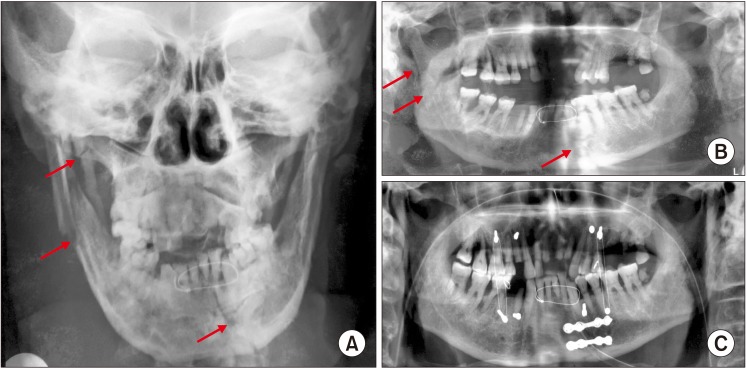

| Fig. 1A. Posteroanterior radiograph with arrows showing ipsilateral ramus fracture with styloid process fracture and contralateral parasymphysis fracture. B. Preoperative orthopantamogram (OPG) with arrows showing ipsilateral ramus fracture with styloid process fracture and contralateral parasymphysis fracture. C. Fifteen days postoperative OPG.

|

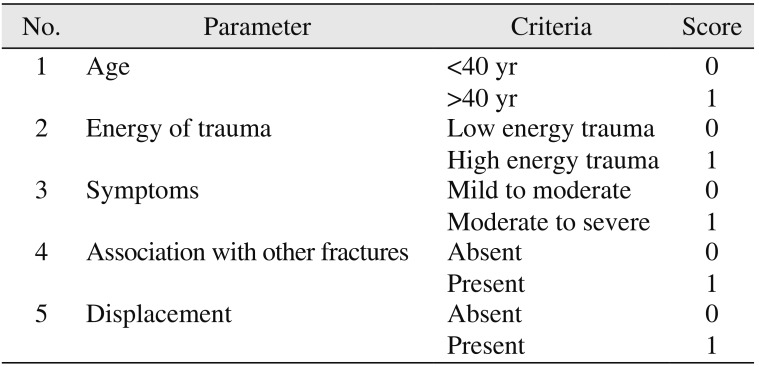

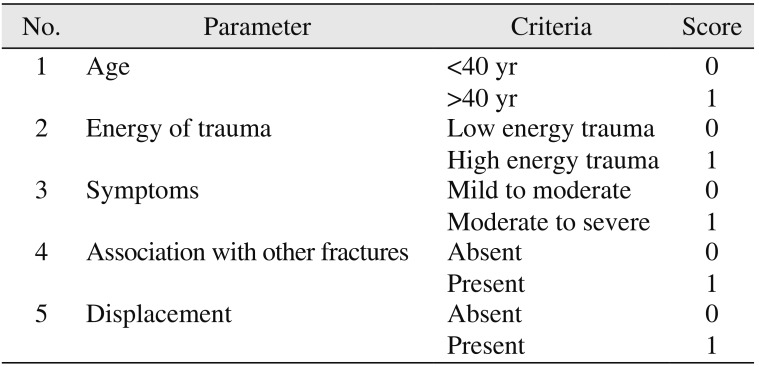

Five epidemiological parameters (

Table 2) are considered, with points given for fundamental elements in grading fracture types. These five parameters are (1) age, (2) energy of trauma, (3) symptoms, (4) association with other fractures, and (5) displacement.

Table 2

Parameters used for scoring

|

No. |

Parameter |

Criteria |

Score |

|

1 |

Age |

<40 yr |

0 |

|

>40 yr |

1 |

|

2 |

Energy of trauma |

Low energy trauma |

0 |

|

High energy trauma |

1 |

|

3 |

Symptoms |

Mild to moderate |

0 |

|

Moderate to severe |

1 |

|

4 |

Association with other fractures |

Absent |

0 |

|

Present |

1 |

|

5 |

Displacement |

Absent |

0 |

|

Present |

1 |

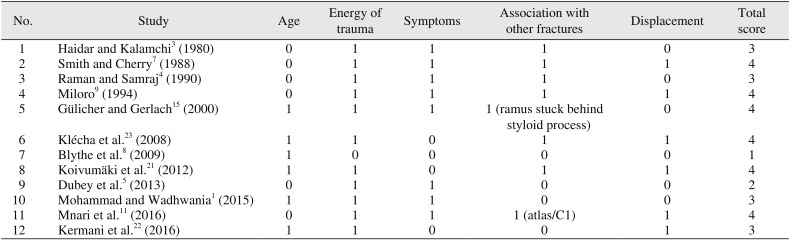

For each of the five fundamental elements, a score of one or zero is given according to the presence or absence of the factor, respectively. Thus, factors can accumulate scores from zero to five points and are grouped into two possible types with increasing severity and complexity.

After verification of the presence of the elemental factors of the score classification (0–5), fractures are classified into two groups: Group I (with scores of 0–2) and Group II (with scores of 3–5).

For all patients over 40 years of age, one point is credited. Zero points are given to patients aged up to 40 years. An age factor of 40 years is specified because most of the literature confirms that elongation or lengthening of SP takes place after 40 years of age. Road traffic accidents, falls from heights, assault, crush injuries, and closed head trauma are categorized as high energy trauma, with one point assigned per incident. Minor incidents such as trauma due to repetitive yawning, coughing, impacted lower third molar removal

16, and rolling over during sleep

17 are examples of low energy trauma and are given a score of zero.

For patients presenting with mild symptoms, a score of zero is given. For severe symptoms of throat pain upon swallowing or neck motion, one point is credited. Similarly, one point is credited for SP fractures associated with other fractures such as mandible or atlas/C1 fractures, while zero points are given if there is no association with other fractures. For fractures with displacement/deviation in radiographic assessment, one point is credited. For undisplaced fractures, zero points are given.

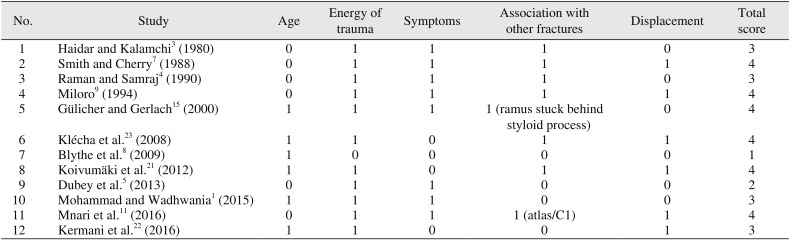

• Group I (scores of 0 to 2): Fractures with a maximum score of 2 points and relatively greater stability. They correspond to fractures in younger patients with low energy trauma or to fractures in patients over 40 years of age with no deviation or displacement of fractured styloid fragments. Group I fractures are usually managed conservatively and have a good prognosis.(

Table 3)

Table 3

Scores of reported cases

|

No. |

Study |

Age |

Energy of trauma |

Symptoms |

Association with other fractures |

Displacement |

Total score |

|

1 |

Haidar and Kalamchi3 (1980) |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

|

2 |

Smith and Cherry7 (1988) |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

|

3 |

Raman and Samraj4 (1990) |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

|

4 |

Miloro9 (1994) |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

|

5 |

Gülicher and Gerlach15 (2000) |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 (ramus stuck behind styloid process) |

0 |

4 |

|

6 |

Klécha et al.23 (2008) |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

|

7 |

Blythe et al.8 (2009) |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

8 |

Koivumäki et al.21 (2012) |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

|

9 |

Dubey et al.5 (2013) |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

10 |

Mohammad and Wadhwania1 (2015) |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

|

11 |

Mnari et al.11 (2016) |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 (atlas/C1) |

1 |

4 |

|

12 |

Kermani et al.22 (2016) |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

• Group II (scores of 3 to 5): Fractures with a score of 3 to 5 points. Group II fractures correspond to fractures with displacement and to those associated with other fractures. Due to severity of symptoms, group II fractures are potentially unstable. They generally require surgical intervention with good stabilization, and prognosis is dependent on surgical removal of fractured styloid fragments along with treatment of associated fractures.(

Table 3)

• Clinical presentation: Clinical examination and radiological investigation are essential in diagnosing and appropriately planning individual patient management. Trauma to the SP, although rarely discussed, can result in clinical symptoms of cervico-facial pain. Patients can have symptoms related to compression and irritation of cranial nerves (V, VII, IX, and X), including facial pain while turning the head

4, dysphagia

3, foreign body sensation, pain on protruding the tongue, temporomandibular joint dysfunction pain, change in voice, sensation of hypersalivation, tinnitus, or otalgia

4. Sometimes, these symptoms are experienced with intermittent syncope. Intra-orally, symptoms would increase—ideally, for purposes of clinical diagnosis—on palpation. The clinical diagnosis of styloid fracture is always confirmed by imaging, which includes orthopantomograms, computed tomography (CT) scans

18, and conventional radiographs in lateral and posteroanterior views

319. The use of CT or cone-beam CT (CBCT) scans with or without three-dimensional reconstruction is essential to establish the occurrence of a traumatic SP. Surgical removal of fractured styloid fragments is mandatory when the fracture is in close proximity to vital structures

20212223. If pain is reproduced with simultaneous turning of a patient's head to the contralateral side and swallowing, then there should be a heightened index of suspicion for the presence of Eagle's syndrome

212223. Patients with chronic vague, generalized pain, with dysphagia, and with a sore throat and functional limitations in neck movement are ideal cases for surgical removal of fractured styloid fragments. If these cases are associated with mandibular fractures, ORIF with or without intermaxillary fixation (IMF) can be performed along with simultaneous removal of the fractured styloid fragment

2223.

Go to :

III. Proposed Classification

According to a critical review of the literature, SP fractures are classified based on the following.

• Based on displacement: Classifications include undisplaced fractures and displaced fractures.

• Based on the cause and grade of an impact: Classifications include intrinsic and extrinsic trauma.

• Based on fracture level: Classifications are high-level fractures and low-level fractures.

• Based on the direction of impact: Classifications are fractures from direct or indirect impact.

• Based on involvement: Classifications are unilateral or bilateral.

Although SP fractures are mentioned in previous literature, the terms “stylomandibular complex fractures” and “cervicostylomandibular fractures” are rarely used. We present herewith a comprehensive classification of stylo-mandibular fractures along with C1 fractures.

Go to :

IV. Classification of Cervico-Stylo-Mandibular Fractures

-

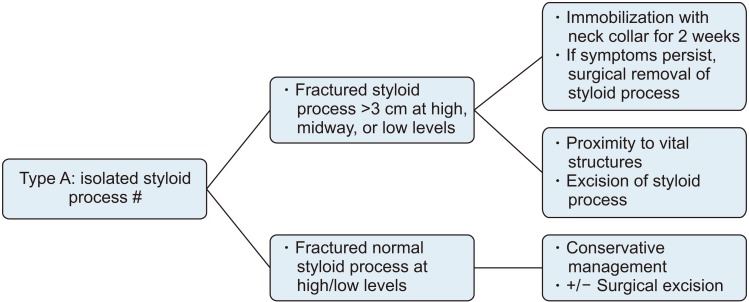

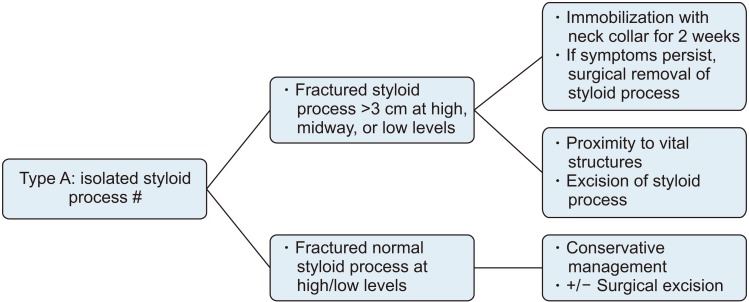

1. Type A: Isolated SP fractures (Fig. 2)

-

2. Type B: Stylomandibular fractures (Fig. 3)

-

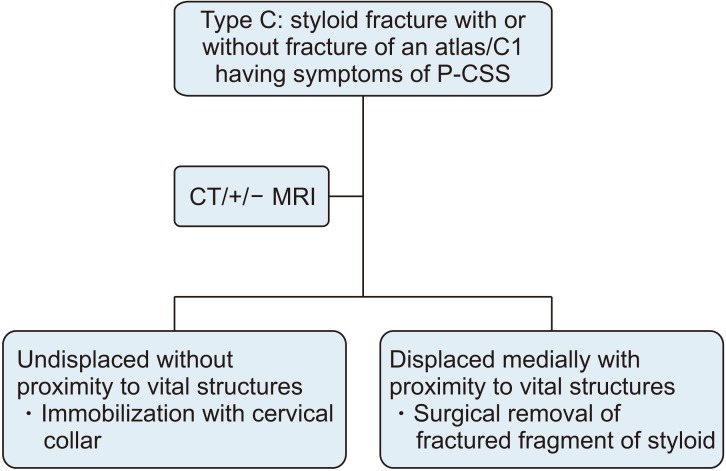

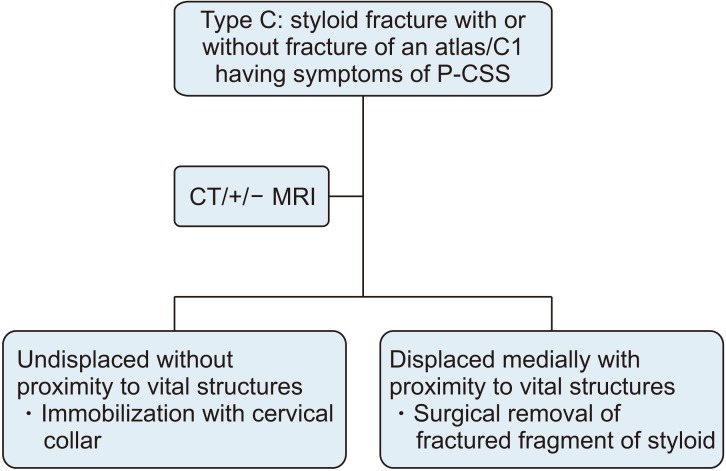

3. Type C: Cervico-stylo-mandibular fractures (Fig. 4): fractures associated with fracture of the atlas/C1

| Fig. 2Treatment algorithm for type A: Isolated styloid process fracture.

|

| Fig. 3Treatment algorithm for type B: Stylo-mandibular fractures. (OPG: orthopantamogram, CT: computed tomography, ORIF: open reduction and internal fixation, MMF: maxillomandibular fixation)

|

| Fig. 4Treatment algorithm for type C: Cervico-mandibular fractures or fractures associated with fracture of the atlas/C1. (P-CSS: post-traumatic Collet-Sicard syndrome, CT: computed tomography, MRI: magnetic resonance imaging)

|

Management of an isolated SP depends on the severity and amount of fractured SP displacement. Surgical removal may be necessary when either the SP is elongated or is severely displaced with close proximity to vital structures. In isolated SP fractures with mild discomfort, conservative treatment may be appropriate and sufficient. Conservative treatment in these cases includes analgesics and/or muscle relaxants with restriction of neck movement for several weeks to give the fracture site a chance to heal.

A clinical diagnosis of styloid fracture associated with mandibular fracture is difficult and misleading, because in many cases, a fractured SP may not be palpable at the tonsillar fossa region, and all the associated symptoms might be common to a mandibular angle fracture. Styloid fracture becomes evident only on orthopantamogram (OPG) and CT. For all intents and purposes, styloid fractures can be grouped into displaced or undisplaced.

For an undisplaced SP fracture, it is advisable to undergo OPG with an open mouth view. If a change in styloid position is revealed, then it is important to maintain IMF for 2 weeks following ORIF for mandibular fracture.

In cases of displaced SP fracture, it is always better to perform CT. If the CT shows proximity of the fracture to vital structures, then surgical removal of the styloid fracture fragment along with ORIF of the mandible should be the treatment of choice. If the fractured SP is not close to vital structures, then ORIF of the mandible with or without IMF is initially advised. Excision of the fractured styloid fragment should be considered only if the fracture becomes symptomatic.

The work of Mnari et al.

11 describes a unique case of a traumatic SP causing palsy of the lower cranial nerves. Similarly, Domenicucci et al.

10 reports a case of post-traumatic Collet-Sicard syndrome. Collet-Sicard syndrome appearing secondary to a SP fracture is rare, and only a few case reports are available in the literature. Dettling et al.

24 report a case with IX, X, and XI cranial nerve deficit with a 50-mm distance from the SP to the transverse process of the atlas on the fractured side. The narrow space between the transverse of the atlas and the SP make the lower cranial nerve vulnerable in the event of trauma. If the SP is abnormally displaced medially following trauma, then this space will be reduced, thereby increasing the likeliness of lower cranial nerve palsies. Therefore, cases of medially displaced SP must be treated with surgical excision of fractured styloid fragments. In contrast, undisplaced SP with no proximity to vital structures can be managed conservatively by immobilization of the cervical collar for 3 to 4 weeks. Surgical excision of the SP may be considered if a patient's symptoms persist.

These cases of styloid fractures with characteristics of Collet-Sicard syndrome may also be associated with atlas fracture. It is advisable to perform magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) along with CT for better depiction of soft tissues around the fractured SP. MRI also stands to reveal drooping and flabby aspects of the oropharyngeal wall on the fractured side or a deviated tongue related to paralysis of the IX and XII cranial nerves.

Go to :

V. Conclusion

In conclusion, SP fractures may also be associated the cervico-mandibular region. It is important to determine the mode of treatment, either conservatively or surgically, based on the clinical severity of fractures. Surgery must be considered if a fractured fragment is found in close proximity to vital structures. The potential complications of post-traumatic styloid syndrome can be avoided with adequate treatment. Presentation of this classification would be easy to apply to guide prognosis and treatment for cervico-stylo-mandibular fractures. The main reasons for proposing a new classification system come both from our experience with clinical subjects involving these fractures and also based on the available literature. Consideration of the parameters presented here is grounded in the available scientific evidence. The empirical challenge of developing a severity classification system with the ability to assist in treatment and making prognoses is still a matter of debate.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download