Abstract

Background/Aims

Current knowledge and viewpoints regarding biosimilars among physicians in Asia are unknown, even though these were investigated by European Crohn's and Colitis Organization (ECCO) members in 2013 and 2015. Thus, this study conducted a multinational survey to assess the awareness of biosimilar monoclonal antibodies among Asian physicians.

Methods

A 17-question multiple-choice anonymous web survey was conducted with the logistic support of the Asian Organization of Crohn's and Colitis (AOCC). Randomly selected AOCC members were invited by e-mail to participate between February 24, 2017 and March 26, 2017.

Results

In total, 151 physicians from eight Asian countries responded to the survey. Most of the participants were gastroenterologists (96.6%), and 77.5% had cared for inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) patients for more than 5 years. The majority of the respondents (66.2%) were aware that a biosimilar is similar but not equivalent to the originator. The majority of respondents (77.5%) considered cost saving to be the main advantage of biosimilars, but a high percentage of respondents (38.4%) were concerned about a different immunogenicity from that of the originator (92.4% and 27.1% respectively in ECCO 2015). Only 19.2% considered that the originator and biosimilars were interchangeable, and only 6.0% felt very confident in the use of biosimilars (44.4% and 28.8% respectively in ECCO 2015).

Conclusions

Asian gastroenterologists in 2017 are generally well informed about biosimilars. On the other hand, compared to the ECCO members surveyed in 2015, Asian gastroenterologists had more concerns and less confidence about the use of biosimilars in clinical practice. Thus, IBD-specific data on the comparison of the efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity in Asian patients are needed.

The introduction of biological therapies has led to marked changes in the management of debilitating immune-mediated inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), including ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD).12 On the other hand, the long-term use of these agents may be costly, placing a significant burden on the National Healthcare System. The development of the first biosimilar to infliximab, CT-P13 (Remsima®; Celltrion Inc., Incheon, Korea, and Inflectra®; Hospiral, Lake Forest, IL, USA) was conceived to decrease the medical care costs and increase the patient treatment options. Recently, infliximab biosimilar monoclonal antibodies (mAb) have been approved for IBD. The current knowledge and viewpoints regarding biosimilars among European physicians were investigated by European Crohn's and Colitis Organization (ECCO) members in 2013. The survey showed that a minority of IBD specialists were aware and confident about the benefits and issues of biosimilars.3 In 2015, an ECCO survey was conducted to examine the evolution of IBD specialists' views after 2 years. The opinion of IBD experts on the use of biosimilar monoclonal antibodies has changed dramatically toward a more favorable and confident position.4 These might be because of the increased knowledge from postgraduate education and published evidence from clinical practice.

Although the incidence of IBD in Asia has increased rapidly in recent years5678 and the first infliximab biosimilar, CT-P13 (Remsima®; Celltrion Inc.), was produced by a Korean biopharmaceutical company and licensed for the Korean market in 2012, the current knowledge and viewpoints regarding biosimilars among physicians in Asia is unknown. Therefore, this study conducted a multinational survey to assess the awareness of biosimilar mAb among physicians in Asian countries.

This study adopted the questions used to survey ECCO members in 2013, 2015 or both. In 2013, a 15-question multiple- choice anonymous web survey was conducted in Europe, with questions covering the most relevant aspects of biosimilars.3 In 2015, a 14-question multiple-choice anonymous web survey was conducted in Europe again. Most of the questions used in 2013 were retained, but other questions were added or adapted on some new issues relevant to biosimilars in IBD.4

In this study, a 17-question multiple-choice anonymous web survey was performed with the logistic support of the Asian Organization of Crohn's and Colitis (AOCC) (Supplementary Table 1). Randomly selected AOCC members were invited by e-mail to participate between February 24, 2017, and March 26, 2017 and their responses were provided to the coauthors for analysis.

Referring to the published results of 2013 and 2015 ECCO surveys,34 a simple comparison between European and Asian participant responses was performed with no statistical analysis. Within Asian countries, a chi-square test was performed to compare the results between countries. p-values ≤0.05 were considered significant. All calculations were performed using SPSS ver. 24.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Initially, 320 AOCC members were selected randomly and invited to this study. The response rate was 47%. Overall, 151 physicians from eight Asian countries (Korea, Japan, China, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Taiwan, Singapore, and India) responded to the survey (Table 1). Most participants were gastroenterologists (96.6%), including IBD specialists (67.5%). Of these, 94% worked in academic teaching hospitals, and 77.5% had cared for IBD patients for more than 5 years. Similar to the ECCO members response in 2015, the majority (49.6%) had access to biosimilars and had already prescribed them, whereas 26.4% had access to biosimilars but had not yet prescribed them, and 19% of respondents had no access to biosimilars (ECCO members in 2015: 60%, 22%, and 18%, respectively). Within Asian countries, a higher proportion of physicians in Korea (41.5%) had prescribed biosimilars for more than 2 years compared to other countries (Japan 4.3%, China 20.6%, and others 0%, p<0.001) (Supplementary Table 2).

In the definition of mAb, the majority of respondents (66.2%) were aware that a biosimilar is a similar product, but not equal to the originator; 27.8% responded that it is a copy of a biological agent, identical to the originator (like a generic), and a further 8% confused a biosimilar with a different anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agent, like adalimumab to infliximab, which was similar to the ECCO members response in 2013 (70%, 19%, and 8%, respectively). Interestingly, among Asian countries, a higher proportion of physicians in Korea (47.2%) defined a mAb as a copy of a biological agent that was identical to the originator compared to participants from other Asian countries (Japan 4.3%, China 20.6%, and others 0%, p<0.001) (Supplementary Table 2).

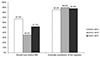

With regard to the issues or advantages of biosimilar mAb, 19.9% of respondents estimated that biosimilars had different activities than the originator, and 38.4% of respondents estimated that these would present a different immunogenicity pattern than the originator, proportions which were similar to the ECCO members' opinions in 2015 (16.9% and 27.1% respectively), but lower than those of the ECCO members in 2013 (43% and 67% respectively) (Fig. 1). On the other hand, a smaller percentage of respondents (77.5%) considered cost saving to be the main advantage of biosimilars compared to 92.4% of ECCO members in 2015 and 89.5% in 2013 (Fig. 1). Within Asian countries, a higher proportion of physicians in Korea (47.2%) believed that biosimilars would have only a marginal impact on the healthcare costs (Japan 27.7%, China 5.9%, and others 11.8%, p=0.002) (Supplementary Table 2).

Compared to other biosimilars available (erythropoietin, growth factors, etc.), 41.7% of respondents thought that mAb were more complex agents than other biosimilars, and thus had a higher risk of not being sufficiently similar. Approximately 45% of respondents believed that biosimilars required well-designed clinical trials evaluating each indication for which the originator was approved, which was lower than the ECCO 2013 respondents (62% and 65% respectively), but higher than those of the ECCO 2015 (32% and 27% respectively). Similar to the ECCO 2015 (54%) results, 53.6% of respondents believed that biosimilars required more accurate post-marketing pharmacovigilance.

Of the physicians who participated in the survey, 51.7% agreed that biosimilars should carry distinct International Nonproprietary Names (INN), which was lower than the results from the ECCO 2013 (67%), but higher than the ECCO 2015 (35%) survey (Fig. 2). Within Asian countries, a higher proportion of physicians in China (73.5%) thought that biosimilars should carry distinct INN (Korea 54.7%, Japan 29.8%, and others 58.5%, p=0.006) (Supplementary Table 2).

Most respondents (86.7%) disagreed with the automatic substitution of the originator with a biosimilar by a pharmacist, which was generally in line with the findings among ECCO members (85% in 2013 and 89.8% in 2015) (Fig. 2). In a detailed questionnaire regarding which specific cases should be applied to automatic substitution, most respondents (44.3%) said automatic substitution should not be applied in all kinds of cases. Within Asian countries, a higher proportion of physicians in Korea (62.3%) disagreed with automatic substitution in any case (Japan 38.3%, China 11.8, and others 12.6%, p<0.001) (Supplementary Table 2).

When participants were asked, in the case of an IBD patient in prolonged remission under an originator mAb, whether the scheduled therapy should be continued with a biosimilar, 36.4% disagreed citing a lack of disease-specific evidence of interchangeability (72.2% in ECCO 2013 and 39.9% in ECCO 2015); 49.7% agreed but stated that they would provide detailed information to their patient regarding the limited data on the safety of the biosimilar (22% in ECCO 2013 and 27.4% in ECCO 2015), and only 19.2% said the two molecules were interchangeable (6% in ECCO 2013 and 44.4% in ECCO 2015).

In the theoretical case of a randomized controlled trial for rheumatology patients showing no differences between a biosimilar and its originator, 39.1% believed the biosimilar should be approved for all indications of the originator (24.2% in ECCO 2013 and 50.8% in ECCO 2015). In the case of IBD, in which a theoretical randomized controlled trial showed no differences between a biosimilar and the originator in CD, 52.3% would use it only in CD (53% in ECCO 2013 and 25% in ECCO 2015); 21.2% would also use the biosimilar in UC (16% in ECCO 2013 and 31% in ECCO 2015), and 23.8% would still wait for more evidence for both CD and UC (30% in ECCO 2013 and 8.6% in ECCO 2015) (Fig. 3).

For the actions required of medical societies, 45.7% thought that medical societies should promote information on biosimilars (66% in ECCO 2013 and 75% in ECCO 2015), and 55.6% of respondents expressed a need for collaboration with health institutions to develop a consensus on the use of biosimilars (compared to 78% in ECCO 2013 and 47% in ECCO 2015); 58.3%, recommended the development of multispecialty practice guidelines (compared to 57% in ECCO 2013 and 26% in ECCO 2015), and 63.6% recommended the development of multispecialty safety registries (compared to 81% in ECCO 2013 and 52% in ECCO 2015).

Finally, when asked whether they would feel confident in prescribing biosimilars to their participants, only 6.0% felt confident in the use of biosimilars compared to 5% and 28.8% of ECCO members in 2013 and 2015, respectively (Fig. 4). When the association between the degree of confidence and access to biosimilars was analyzed, participants who had never prescribed these agents or participants from countries in which these agents were unavailable showed a higher proportion of little or no confidence (Spearman's r=−0.31, p<0.001) (Fig. 5).

The first infliximab biosimilar was introduced to the European market in 2013, and a survey investigating the opinions of European IBD physicians was undertaken with the logistic support of the ECCO in 2013 and subsequently in 2015.34 The 2015 survey indicated that almost double the proportion of respondents were in favor of increasing the use of biosimilars, with limited concerns regarding their safety, compared to the 2013 survey.4 The present survey showed that Asian gastroenterologists in 2017 were generally as well informed of the definitions of biosimilars, as were ECCO members in 2015, and the concerns about immunogenicity were not as high as ECCO members in 2015. On the other hand, there were more concerns regarding the concept of extrapolation across indications and less confidence about their use in clinical practice than those among ECCO members in 2015.

The first infliximab biosimilar, CT-P13 (Remsima®; Celltrion Inc.), was manufactured by a Korean biopharmaceutical company and was licensed for the market in Korea in 2012. Subsequently, CT-P13 (Remsima®; Celltrion Inc.) was introduced across Asia, first in Japan in 2014, then in Taiwan and Singapore in 2016, and recently in Hong Kong in 2017. Therefore, most of the participants (112/151, 74.2%) in the present study had biosimilars available for their clinical practice, and they were generally as well informed of the definitions of biosimilars as the ECCO members in 2015. On the other hand, there was a difference in the duration of biosimilar prescription among physicians within Asian countries. The proportion of physicians in Korea who prescribed biosimilars for more than 2 years was 41.5% in Korea, 20.6% in China, and less than 5% in other Asian countries (Supplementary Table 2). In addition, a proportion of Asian gastroenterologists still had misconceptions regarding biosimilars, viewing them as generic copies of the original biologic agents. Compared to ECCO members, a lower percentage of respondents considered lower prices as the main advantage of biosimilars in this study. An explanation may be that because Asian governments are using pharmaceutical pricing strategies to contain rising healthcare costs, there is a relatively small price difference between the originators and biosimilars.9 In particular, the single price system is applied in Korea so that the prices of the innovator drug and its alternative have become similar.10 In Asia, although the concerns of immunogenicity were not serious, they were higher than ECCO 2015, and the proportion of respondents who thought that each biosimilar should carry a distinct INN was higher than ECCO 2015.

In the present survey, there were more concerns regarding the extrapolation of biosimilars across indications and less confidence about their use in clinical practice than for the ECCO members in 2015. The reason might be that there have been few studies supporting the safety and effectiveness of infliximab biosimilars in the Asian IBD population, as all published studies were conducted in Korea.1112 A retrospective multicenter study evaluated the clinical efficacy and safety of CT-P13 (Remsima®; Celltrion Inc.) in 32 anti-TNF-naïve CD patients and 42 anti-TNF-naïve UC patients.11 In anti-TNF-naïve CD patients, the remission rates were 68.8%, 84.4%, 77.3%, and 75.0% at 2, 8, 30, and 54 weeks. In anti-TNF-naïve UC patients, remission rates were 19.0%, 38.1%, 47.8% and 50.0% at 2, 8, 30, and 54 weeks. In another post-marketing study, which included patients with active moderate-to-severe CD, fistulizing CD, or moderate-to-severe UC treated with CT-P13 (Remsima®; Celltrion Inc.),12 treatment-related adverse events occurred in 10% of patients and were mostly mild-moderate in severity. Positive outcomes for response/remission were reported regardless of whether the patients had received prior infliximab or not.

Currently, prospective randomized non-inferiority trials evaluating the clinical efficacy and safety, as well as the interchangeability of biosimilars in Korean IBD patients are ongoing.13 In Western countries, clinical evidence regarding biosimilars is derived from cohort studies on IBD patients, both in CD and UC.1415161718192021222324 Although the extrapolation for use in other indications is essential to keep the cost of biosimilars competitive, well-designed, prospective randomized non-inferiority trials for efficacy and safety, as well as immunogenicity and interchangeability will be needed before clinicians confidently integrate biosimilars into IBD treatment. In addition, as the physician's accessibility and experience derived from the follow-up time to the prescription were associated with increased confidence in using biosimilars in clinical practice in this survey, both clinical evidence and individual experience might be needed. This study had limitations in that because most of the responders were from three Asian countries (Korea, Japan, and China), it will be difficult for the survey result to represent other Asian physicians' knowledge and viewpoints. Therefore, this survey should be conducted on other Asian physicians' in the future.

In conclusion, Asian gastroenterologists are generally well informed about biosimilars. On the other hand, compared to ECCO members in 2015, Asian gastroenterologists had more concerns and less confidence about the use of biosimilars in clinical practice. Thus, IBD-specific data on a comparison of the efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity in Asian patients will be needed.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Issues or advantages of monoclonal antibodies biosimilars. ECCO, European Crohn's and Colitis Organization; AOCC, Asian Organization of Crohn's and Colitis. |

| Fig. 2Interchangeability and automatic substitution. ECCO, European Crohn's and Colitis Organization; AOCC, Asian Organization of Crohn's and Colitis; INN, International Nonproprietary Names. |

| Fig. 3Responses hypothesizing that a randomized controlled trial showed no difference between a biosimilar and the originator in CD. ECCO, European Crohn's and Colitis Organization; AOCC, Asian Organization of Crohn's and Colitis; CD, Crohn's disease; UC, ulcerative colitis. |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully thank Silvio Danese for permission to formulate the questions for this study, which were based on the ECCO member surveys in 2013 and 2015 and thank Tadakazu Hisamatsu, Zhihua Ran, and Shu Chen Wei for collecting data.

References

1. Katsanos KH, Papadakis KA. Inflammatory bowel disease: updates on molecular targets for biologics. Gut Liver. 2017; 11:455–463.

2. Park DI. Current status of biosimilars in the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases. Intest Res. 2016; 14:15–20.

3. Danese S, Fiorino G, Michetti P. Viewpoint: knowledge and viewpoints on biosimilar monoclonal antibodies among members of the European Crohn's and Colitis Organization. J Crohns Colitis. 2014; 8:1548–1550.

4. Danese S, Fiorino G, Michetti P. Changes in biosimilar knowledge among European Crohn's Colitis Organization [ECCO] members: an updated survey. J Crohns Colitis. 2016; 10:1362–1365.

5. Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2018; 390:2769–2778.

6. Ng WK, Wong SH, Ng SC. Changing epidemiological trends of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia. Intest Res. 2016; 14:111–119.

7. Ooi CJ, Makharia GK, Hilmi I, et al. Asia pacific consensus statements on Crohn's disease. Part 1: definition, diagnosis, and epidemiology: (Asia pacific Crohn's disease consensus--part 1). J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016; 31:45–55.

8. Yang SK, Yun S, Kim JH, et al. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in the Songpa-Kangdong district, Seoul, Korea, 1986-2005: a KASID study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008; 14:542–549.

9. Verghese NR, Barrenetxea J, Bhargava Y, Agrawal S, Finkelstein EA. Government pharmaceutical pricing strategies in the Asia-Pacific region: an overview. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2019; 7:1601060.

10. Hasan SS, Kow CS, Dawoud D, Mohamed O, Baines D, Babar ZU. Pharmaceutical policy reforms to regulate drug prices in the Asia Pacific region: the case of Australia, China, India, Malaysia, New Zealand, and South Korea. Value Health Reg Issues. 2019; 18:18–23.

11. Jung YS, Park DI, Kim YH, et al. Efficacy and safety of CT-P13, a biosimilar of infliximab, in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a retrospective multicenter study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015; 30:1705–1712.

12. Park SH, Kim YH, Lee JH, et al. Post-marketing study of biosimilar infliximab (CT-P13) to evaluate its safety and efficacy in Korea. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015; 9 Suppl 1:35–44.

13. Kim YH, Ye BD, Pesegova M, et al. Phase III randomized, double-blind, controlled trial to compare biosimilar infliximab (CT-P13) with innovator infliximab (INX) in patients with active Crohn's disease: early efficacy and safety results. Gastroenterology. 2017; 152:S65.

14. Jahnsen J, Detlie TE, Vatn S, Ricanek P. Biosimilar infliximab (CT-P13) in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a Norwegian observational study. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015; 9 Suppl 1:45–52.

15. Keil R, Wasserbauer M, Zádorová Z, et al. Clinical monitoring: infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 in the treatment of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2016; 51:1062–1068.

16. Smits LJ, Derikx LA, de Jong DJ, et al. Clinical outcomes following a switch from remicade® to the biosimilar CT-P13 in inflammatory bowel disease patients: a prospective observational cohort study. J Crohns Colitis. 2016; 10:1287–1293.

17. Argüelles-Arias F, Guerra Veloz MF, Perea Amarillo R, et al. Effectiveness and safety of CT-P13 (biosimilar infliximab) in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in real life at 6 months. Dig Dis Sci. 2017; 62:1305–1312.

18. Gecse KB, Lovász BD, Farkas K, et al. Efficacy and safety of the biosimilar infliximab CT-P13 treatment in inflammatory bowel diseases: a prospective, multicentre, nationwide cohort. J Crohns Colitis. 2016; 10:133–140.

19. Kaniewska M, Moniuszko A, Rydzewska G. The efficacy and safety of the biosimilar product (inflectra®) compared to the reference drug (remicade®) in rescue therapy in adult patients with ulcerative colitis. Prz Gastroenterol. 2017; 12:169–174.

20. Farkas K, Rutka M, Golovics PA, et al. Efficacy of infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 induction therapy on mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2016; 10:1273–1278.

21. Fiorino G, Ruiz-Argüello MB, Maguregui A, et al. Full interchangeability in regard to immunogenicity between the infliximab reference biologic and biosimilars CT-P13 and SB2 in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018; 24:601–606.

22. Smits LJT, Grelack A, Derikx LAAP, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes after switching from remicade® to biosimilar CT-P13 in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2017; 62:3117–3122.

23. Boone NW, Liu L, Romberg-Camps MJ, et al. The nocebo effect challenges the non-medical infliximab switch in practice. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018; 74:655–661.

24. Schmitz EMH, Boekema PJ, Straathof JWA, et al. Switching from infliximab innovator to biosimilar in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a 12-month multicentre observational prospective cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018; 47:356–363.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download