This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Purpose

The Korean Association of Pediatric Surgeons (KAPS) performed a nationwide survey on sacrococcygeal teratoma in 2018.

Methods

The authors reviewed and analyzed the clinical data of patients who had been treated for sacrococcygeal teratoma by KAPS members from 2008 to 2017.

Results

A total of 189 patients from 18 institutes were registered for the study, which was the first national survey of this disease dealing with a large number of patients in Korea. The results were discussed at the 34th annual meeting of KAPS, which was held in Jeonju on June 21–22, 2018.

Conclusions

We believe that this study could be utilized as a guideline for the treatment of sacrococcygeal teratoma to diminish pediatric surgeons' difficulties in treating this disease and thus lead to better outcomes.

Keywords: Teratoma, Sacrococcygeal region, Surveys and questionnaires

INTRODUCTION

Since 1991, the Korean Association of Pediatric Surgeons (KAPS) has performed annual nationwide studies, each year addressing a different topic relating to pediatric diseases, and the results of these studies are discussed at each respective annual meeting of KAPS. They are also summarized and published in

Advances in Pediatric Surgery, the official journal of the KAPS. The list of study topics is summarized in

Table 1. The 34th annual meeting of KAPS was held in Jeonju on June 21–22, 2018, and the topic was sacrococcygeal teratoma, which was discussed for the first time at an annual meeting of KAPS.

Table 1

The list of topics addressed at each annual meeting of the Korean Association of Pediatric Surgeons since 1991

|

Year and topic |

|

1991 |

Current situation in Korean pediatric surgery |

2005a)

|

Necrotizing enterocolitis |

|

1992 |

Inguinal hernia |

2006a)

|

Acute appendicitis |

|

1993 |

Hirschsprung disease |

2007 |

Prospect of pediatric surgery |

|

1994 |

Anorectal malformation |

2008 |

Inguinal hernia |

|

1995a)

|

Esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula |

2009 |

Hirschsprung disease |

|

1996a)

|

Branchial anomalies |

2010a)

|

Intestinal atresia |

|

1997a)

|

Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis |

2011a)

|

Biliary atresia |

|

1998a)

|

Intestinal atresia |

2012 |

Statistics of pediatric surgery disease |

|

1999a)

|

Anorectal malformations |

2013a)

|

Minimally invasive surgery |

|

2000a)

|

Index cases in pediatric surgery |

2014a)

|

Newborns surgery with congenital anomalies |

|

2001a)

|

Biliary atresia |

2015a)

|

Neonate congenital Bochdalek hernia |

|

2002a)

|

Choledochal cyst |

2016 |

Esophageal atresia with tracheoesophageal fistula |

|

2003a)

|

Congenital posterolateral diaphragmatic hernia |

2017 |

Choledochal cyst |

|

2004 |

Trend of pediatric surgery disease |

2018a)

|

Sacrococcygeal teratoma |

METHODS

The authors reviewed and analyzed the clinical data of patients who had been treated for sacrococcygeal teratoma by KAPS members from 2008 to 2017. We used Microsoft Access 2016® (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) for the patient registry and data collection. All the data were analyzed using IBM SPSS version 23 statistical software (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA), and p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

1. Demographics

A total of 189 patients with sacrococcygeal teratoma from 18 institutes were registered for the study (

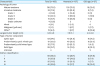

Fig. 1). The top 4 institutes treated 73.5% of all the patients during the study period. The patients' demographics are summarized in

Table 2. The disease was found to have occurred predominantly in females (M:F=1:2.71). A total of 37 accompanying malformations were present in 29 patients (15.3%), and 15 of these patients were diagnosed with Currarino syndrome. Most patients (n=137, 72.5%) were diagnosed and underwent surgery during the neonatal period, but 27 (14.3%) patients underwent surgery beyond the age of 1 year. In this study, we compared the results of the neonates who were younger than 29 days with those of the “old-age” group, which comprised patients who were older than 1 year.

| Fig. 1Hospital distribution of the patients with sacrococcygeal teratoma who underwent surgical treatment.

|

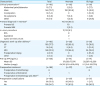

Table 2

Patient demographics

|

Characteristic |

Value |

|

Sex (M:F) |

1:2.71 (51:138) |

|

Gestational age (wk, n=176) |

37.9±2.8 |

|

Birth weight (kg, n=179) |

3.18±0.52 (0.97–4.71) |

|

Mode of delivery |

|

|

Normal spontaneous vaginal delivery |

76 (40.2) |

|

C-section |

100 (52.9) |

|

Unknown |

23 |

|

Accompanied malformation |

29/189a) (15.3) |

|

Cardiovascular |

8 |

|

Gastrointestinal |

5 |

|

Genitourinary |

4 |

|

Musculoskeletal |

4 |

|

Chromosomal |

2 |

|

Other |

6 |

|

Currarino syndrome |

15 |

|

Age at time of surgery |

|

|

<29 day |

137 |

|

29 day–2 mo |

6 |

|

2–3 mo |

7 |

|

3–12 mo |

12 |

|

>12 mo |

27 |

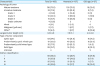

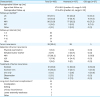

2. Preoperative evaluation and treatment

The most common symptom was sacral mass, and 85.6% of the neonates were diagnosed prenatally. Ultrasonography was the most common diagnostic tool in the prenatal period, but magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was the most popular study after birth. Eleven patients underwent an in-utero procedure. Preoperative serum levels of α-fetoprotein (AFP) were evaluated in 138 patients, and it was the most common tumor marker, followed by β-human chorionic gonadotropin and carcinoembryonic antigen. Almost all the patients underwent surgical treatment without preoperative treatment, with only 8 patients requiring preoperative chemotherapy or embolization. Anterior displacement of the rectum and obstructive hydronephrosis were the most common preoperative complications because of the mass effect of the tumor (

Table 3).

Table 3

Preoperative evaluation and treatment

|

Characteristic |

Total |

Neonate |

Old-age |

|

Clinical presentationa)

|

(n=182) |

(n=132) |

(n=26) |

|

Abdominal pain/distension |

13 (7.1) |

5 (3.8) |

2 (7.7) |

|

Mass |

145 (79.7) |

120 (90.9) |

11 (42.3) |

|

Constipation |

10 (5.5) |

0 |

5 (19.2) |

|

No symptoms |

9 (4.9) |

7 (5.3) |

1 (3.8) |

|

Other |

14 (7.7) |

1 (0.8) |

9 (34.6) |

|

Prenatal diagnosis in neonatea)

|

|

113/135 (85.6) |

|

|

Prenatal US |

|

113 |

|

|

Prenatal MRI |

|

3 (2.2) |

|

|

In-utero procedure |

|

11/135 (8.1) |

|

|

RFA |

|

8 |

|

|

Aspiration |

|

2 |

|

|

Cystic-amniotic shunt |

|

1 |

|

|

Diagnostic work-up after deliverya)

|

(n=182) |

(n=132) |

(n=26) |

|

US |

105 (57.7) |

83 (62.9) |

10 (38.5) |

|

CT |

16 (8.8) |

9 (6.8) |

5 (19.2) |

|

MRI |

159 (87.4) |

112 (84.8) |

24 (92.3) |

|

Preoperative biopsy |

4 (2.2) |

0 |

4 (15.4) |

|

Other |

3 (1.6) |

2 (1.5) |

1 (3.8) |

|

Pre-op AFP (ng/mL) |

(n=138) |

(n=111) |

(n=14) |

|

Mean±SD |

|

87,658±77,076 |

20,287±42,396 |

|

Median (range) |

|

64,745 (0.8–600,000) |

2.1 (0.8–150,730) |

|

Preoperative treatment |

(n=189) |

(n=137) |

(n=27) |

|

Preoperative chemotherapy |

6 |

|

6 |

|

Preoperative embolization |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Preoperative chemotherapy and ASCTb)

|

1 |

|

1 |

|

Preoperative complications |

(n=189) |

(n=137) |

(n=27) |

|

Yes |

30 (15.9) |

26 (19.0) |

1 (3.7) |

|

No |

159 (84.1) |

111 (81.0) |

26 (96.3) |

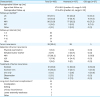

3. Operative treatment

Almost all the neonatal patients underwent surgical treatment without delay. Their median age at the time of surgery was 4 days after birth, and the median body weight was 3.0 kg. Most of the patients underwent surgery once, but 22.2% required an operation more than one time. The perineal approach as a surgical method was so common that 93.7% of the operations were performed using only a perineal approach. A total of 84.1% of the patients underwent complete excision of the tumor, and 21 patients had 24 intra-operative complications among them. Of these, intraoperative bleeding was the most common complication, followed by cerebrospinal fluid leakage. Postoperatively, 15.9% had complications. Problems with the wound constituted the most common postoperative complication and the most common cause of reoperation during the postoperative hospitalization period (

Table 4).

Table 4

Operative treatment

|

Characteristic |

Total (n=189) |

Neonate (n=137) |

Old-age (n=27) |

|

Age at time of surgery (day) |

|

|

|

|

Mean |

305.9±957.1 |

6.9±9.2 |

1,985.3±1,784.9 |

|

Median |

6 (0–7,217) |

4 (0–63) |

1,426 (397–7,217) |

|

No. of operations |

|

|

|

|

1 |

145 (76.7) |

106 (77.4) |

21 (77.8) |

|

2 |

37 (19.6) |

27 (19.7) |

3 (11.1) |

|

3 |

6 (3.2) |

4 (2.9) |

2 (7.4) |

|

5 |

1 (0.5) |

0 |

1 (3.7) |

|

Body weight at time of surgery (kg) |

|

|

|

|

Mean±SD |

6.2±8.8 |

3.1±0.6 |

22.0±15.9 |

|

Median (range) |

3 (2–69) |

3 (2–5) |

16 (8–69) |

|

Operation time |

|

|

|

|

Mean±SD |

148.0±89.6 |

150.3±82.8 |

155.7±129.4 |

|

Median (range) |

125 (20–590) |

132 (20–410) |

110 (34–590) |

|

Mode of surgery |

|

|

|

|

Perineal approach |

177 (93.7) |

131 (95.6) |

23 (85.2) |

|

Perineal+laparotomy/laparoscopic |

9 |

5 |

2 |

|

Others |

3 |

1 |

2 |

|

Results of operation |

|

|

|

|

Complete excision |

159 (84.1) |

116 (84.7) |

23 (85.2) |

|

Complete excision with spillage |

12 (6.3) |

6 (4.4) |

2 (7.4) |

|

Incomplete excision |

18 (9.5) |

15 (10.9) |

2 (7.4) |

|

Intraoperative complications |

21/189 (11.1) |

15/137 (10.9) |

3/27 (11.1) |

|

Bleeding |

8 (38.1) |

6 (40.0) |

2 (66.7) |

|

CSF leakage |

4 (19.0) |

1 (6.7) |

1 (33.3) |

|

CPCR |

4 (19.0) |

4 (26.7) |

0 |

|

Other complications |

6 (28.6) |

5 (33.3) |

0 |

|

Postoperative complicationsa)

|

30/189 |

24/137 |

3/27 |

|

Bleeding |

3 (10.0) |

3 (12.5) |

0 (0) |

|

Wound problem |

17 (56.7) |

14 (58.3) |

1 (33.3) |

|

Intestinal obstruction |

1 (3.3) |

1 (4.2) |

0 (0) |

|

DIC |

5 (16.7) |

5 (20.8) |

0 (0) |

|

Other |

7 (23.3) |

4 (16.7) |

2 (66.7) |

|

Reoperation during hospitalization |

9/189 (4.8) |

7/137 (5.1) |

1/27 (3.7) |

|

Postoperative chemotherapy |

11 (5.8) |

5 (3.6) |

4 (14.8) |

4. Tumor characteristics

The maximal diameters of the tumors in the neonate group were significantly larger than those in the old-age group (7.9±5.1 vs. 4.2±4.8 cm, p<0.001). Using the Altman classification, the most common tumor type was type I in the neonatal group, but type IV was the most common type in the old-age group (p<0.001). Mature and cystic or predominantly cystic mixed type were the main characteristics of the tumors. In this study, we found that the pathologic reports of 12 patients did not belong to teratoma or germ cell tumors, but we included them in this study because their clinical features were more compatible with sacrococcygeal teratoma. A total of 11 patients required postoperative chemotherapy (

Table 5).

Table 5

Tumor characteristics

|

Characteristic |

Total (n=189) |

Neonate (n=137) |

Old-age (n=27) |

|

Pathology of tumor |

|

|

|

|

Mature teratoma |

138 (73.0) |

103 (75.2) |

16 (59.3) |

|

Immature teratoma |

33 (17.5) |

30 (21.9) |

2 (7.4) |

|

|

Grade 1 |

4 (13.8) |

4 (14.8) |

0 (0) |

|

|

Grade 2 |

10 (34.5) |

8 (29.6) |

1 (100) |

|

|

Grade 3 |

15 (51.7) |

15 (55.6) |

0 (0) |

|

|

Grade unknown |

4 (13.8) |

3 |

1 |

|

Mixed |

4 (2.1) |

2 (1.5) |

0 |

|

Malignant (yolk sac) |

2 (1.1) |

1 (0.7) |

1 (3.7) |

|

Othera)

|

12 (6.3) |

1 (0.7) |

8 (29.6) |

|

Largest tumor length (cm) |

6.8±4.8 |

7.9±5.1 |

4.2±4.8 |

|

Type of tumor component |

|

|

|

|

Cystic type |

63 (34.1) |

43 (31.6) |

9 (37.5) |

|

Predominantly cystic mixed type |

61 (33.0) |

48 (35.3) |

6 (25.0) |

|

Predominantly solid mixed type |

32 (17.3) |

29 (21.3) |

1 (4.2) |

|

Solid type |

29 (15.7) |

16 (11.8) |

8 (33.3) |

|

Unknown |

4 |

1 |

2 |

|

Altman classification |

|

|

|

|

I |

68 (36.0) |

53 (38.7) |

8 (29.6) |

|

II |

51 (27.0) |

47 (34.3) |

2 (7.4) |

|

III |

25 (13.2) |

21 (15.3) |

1 (3.7) |

|

IV |

45 (23.8) |

16 (11.7) |

16 (59.3) |

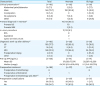

5. Postoperative treatment and follow-up

Postoperative follow-up was available at a median age of 41 months (

Table 6). Most of the patients underwent follow-ups at less than a one-year interval. Ultrasonography and MRI were the most common evaluation methods for follow-up. During the follow-up period, 39 patients had tumor recurrence. The pathological characteristics of the recurrent tumors are described in

Table 7. Thirty-three patients underwent excision or excision with chemotherapy. Long-term complications were found in 44 patients, and most of them correlated with the function of defecation.

Table 6

Postoperative treatment and follow-up

|

Characteristic |

Total (n=189) |

Neonate (n=137) |

Old-age (n=27) |

|

Postoperative follow-up (mo) |

|

|

|

|

Age at last follow-up |

47.9±38.9 (median 41, range 0–243) |

|

Postoperative follow-up |

37.9±27.6 (median 34, range 0–112) |

|

Follow-up methoda)

|

|

|

|

|

US |

89 (47.1) |

66 (48.2) |

13 (48.1) |

|

CT |

23 (12.2) |

17 (12.4) |

4 (14.8) |

|

MRI |

98 (51.9) |

77 (56.2) |

10 (37.3) |

|

PET |

5 (2.6) |

3 (2.2) |

2 (7.4) |

|

Other |

4 (2.1) |

3 (2.2) |

0 (0) |

|

Follow-up interval (mo) |

|

|

|

|

1–3 |

25 |

|

|

|

4–6 |

30 |

|

|

|

7–12 |

37 |

|

|

|

>12 |

14 |

|

|

|

Tumor recurrence |

39 (20.6) |

28 |

5 |

|

Detection of tumor recurrence |

|

|

|

|

Physical examination |

1 (2.6) |

1 (3.6) |

0 (0) |

|

Elevated tumor marker |

3 (7.7) |

3 (10.7) |

0 (0) |

|

MRI |

27 (69.2) |

20 (71.4) |

5 (100) |

|

U/S |

7 (17.9) |

4 (14.3) |

0 (0) |

|

Other |

1 (2.6) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

|

Treatment of tumor recurrence |

|

|

|

|

Excision |

21 (53.8) |

14 (50.0) |

3 (60.0) |

|

Excision+CTx |

12 (30.8) |

9 (32.1) |

1 (20.0) |

|

CTx only |

2 (5.1) |

1 (3.6) |

1 (20.0) |

|

Observation |

2 (5.1) |

2 (7.1) |

0 (0) |

|

Other |

2 (5.1) |

2 (7.1) |

0 (0) |

|

Long-term functional complicationsa)

|

44 |

|

|

|

Constipation |

21 |

|

|

|

Soiling |

14 |

|

|

|

Urinary incontinence |

7 |

|

|

|

Lower extremity weakness |

5 |

|

|

|

Other |

7 |

|

|

Table 7

Recurrent tumor pathology

|

Characteristic |

Total (n=33) |

Neonate (n=23) |

Old-age (n=4) |

|

Mature |

19 (57.6) |

15 (78.9) |

1 (25.0) |

|

Original pathology |

Mature (10), immature (8), mixed (1) |

|

Immature |

2 (6.1) |

2 (8.7) |

0 (0) |

|

Original pathology |

Mature (1), immature (1) |

|

Malignant (yolk sac) |

6 (18.2) |

3 (13.0) |

1 (25.0) |

|

Original pathology |

Mature (3), immature (1), yolk sac (2) |

|

Mixed |

1 (3.0) |

1 (4.3) |

0 (0) |

|

Original pathology |

Mature (1) |

|

Othera)

|

5 (15.2) |

2 (8.7) |

2 (50.0) |

|

Original pathology |

Mature (3), immature (1), epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (1) |

Currently, among the 189 patients, 1 death had occurred in a case of incomplete excision, 136 patients are living without tumors, 19 are living with tumors, and 33 patients have been lost to follow-up (

Fig. 2).

| Fig. 2

Summary of treatments and prognoses.

SCT, sacrococcygeal teratoma; F/U, follow-up.

|

6. Questionnaire for sacrococcygeal teratoma

The questionnaire for sacrococcygeal teratoma consisted of 7 questions, and 22 regular members of KAPS answered them. The following are the questions and the number of answers for each item (

Table 8).

Table 8

Questionnaire for sacrococcygeal teratoma

|

Questionnaire |

No. |

|

1. Which of the following tests are the most important for the preoperative diagnosis of sacrococcygeal teratoma (excluding physical findings and multiple selections available)? |

|

|

① AFP |

12 |

|

② US |

4 |

|

③ CT |

6 |

|

④ MRI |

16 |

|

⑤ Biopsy |

0 |

|

2. Have you needed to do a coccyx resection for patients with sacrococcygeal teratoma? please describe the method and extent of resection. |

|

|

① No resection |

0 |

|

② Resection |

22 |

|

Method: electrical cautery and en bloc resection |

|

|

3. Who do patients follow-up with after surgery? |

|

|

① Pediatric surgeon |

14 |

|

② Pediatrician |

4 |

|

③ Other—both pediatric surgeons and pediatricians (especially in cases of immature or malignant pathologies) |

4 |

|

4. What tests are performed after surgery? (Multiple options are possible.) |

|

|

① AFP |

21 |

|

② US |

11 |

|

③ CT |

4 |

|

④ MRI |

12 |

|

⑤ Other—rectal exam |

1 |

|

5. What is the timing (interval) of the postoperative follow-up? |

|

|

① Every 6 months after surgery |

9 |

|

② Every year after surgery |

7 |

|

③ Every 2 years after surgery |

0 |

|

④ Less than every 6 months after surgery |

4 |

|

6. How long after surgery do you follow-up? (n=20) |

|

|

① Until 1 year after surgery |

0 |

|

② Until 2 years after surgery |

1 |

|

③ Until 3 years after surgery |

3 |

|

④ Until 4 years after surgery |

0 |

|

⑤ Until 5 years after surgery |

13 |

|

⑥ Mature-3 years, immature-5 years |

3 |

|

7. Do you have any experience with minimally invasive surgery for sacrococcygeal teratoma? |

|

|

① Yes |

5 |

|

② No |

17 |

DISCUSSION

Studies on the clinical characteristics of and strategies used to treat sacrococcygeal teratoma are not rare, but its low incidence usually makes it challenging for pediatric surgeons to accumulate experience in this disease. Previous studies about this disease in Korea have been limited, and only a few studies have been published [

1234]. The significance of this study is that it is the first nationwide survey on sacrococcygeal teratoma in Korea and includes a significant number of patients.

Our study showed excellent results after surgical treatment. There was only 1 reported case of death after surgery, and the number of long-term functional complications was not high. Although not all the patients were followed-up for a long time, it is likely that the mortality of those who were lost to follow-up was not affected because the pediatric surgeons would probably have treated them if they had experienced any problems. These results are similar to or better than those of previously published studies [

5678910].

This study revealed that this incidence of this disease can be divided into 2 age groups. In the one group, the lesions were detected prenatally, and in the other, the disease was late-onset. Although the incidence of the old-age group was not high, and the prognosis of this group after surgical treatment was also excellent, pediatric surgeons must consider the possibility of this disease in old age.

One of the limitations of this study was that we evaluated only the patients who underwent surgical treatment, and therefore not all patients with sacrococcygeal teratoma were included. The prognosis of sacrococcygeal teratoma would have deteriorated in patients who could not undergo surgical treatment because of their poor general condition or the inoperability of the tumor.

Through the questionnaire, we were able to learn the current status of KAPS members' clinical practices with regard to sacrococcygeal teratoma. Most of the members take care of their patients themselves postoperatively, and they prefer a long-term follow-up of about 5 years. In rare cases, a few members tried to treat patients using laparoscopic surgery or robotic surgery.

We believe that this study could be utilized as a guideline for the treatment of sacrococcygeal teratoma to diminish pediatric surgeons' difficulties in treating this disease and thus lead to better outcomes.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download