This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to compare the outcomes of open fundoplication (OF) and laparoscopic fundoplication (LF) in children with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the electronic medical charts of pediatric patients who underwent fundoplication for GERD between January 2005 and May 2018 at the Korean tertiary hospital. Patient characteristics, operation type, associated diagnosis, operation history, neurologic impairment, postoperative complication, recurrence, and operation outcomes were investigated. The Mann-Whitney U test or Student's t-test was used to evaluate continuous data as appropriate. The χ2 test was used to analyze categorical data.

Results

A total of 92 patients were included in this study; 50 were male and 42 were female. Forty-eight patients underwent OF and 44 patients underwent LF. Patient characteristics, such as sex ratio, gestational age, symptoms, neurological impairment, and history of the previous operation were not different between the two groups. A longer operative time (113.0±56.0 vs. 135.1±49.1 minutes, p=0.048) was noted for LF. There was no significant difference in operation time when the diagnosis was limited to only GERD, excluding patients with other combined diseases. Other surgical outcomes, such as intraoperative blood loss, transfusion rate, hospital stay, and recurrence rate were not significantly different between the 2 groups. The complication rate was slightly higher in the OF group than in the LF group; however, the difference was not significant (20.8% vs. 11.4%, p=0.344).

Conclusion

LF is as safe, feasible, and effective as OF for the surgical treatment of GERD in children.

Keywords: Gastroesophageal reflux, Fundoplication, Minimally invasive surgical procedures, Pediatrics

INTRODUCTION

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is a disease that is commonly encountered in infants and children. In general, the episodes of GER seen in infants and children are not clinically significant [

1] and have no identifiable etiology. It has been reported that 60% to 65% of children with GER will undergo spontaneous symptom resolution by 2 years of age, regardless of any medical treatment [

2]. However, some children will progress to having pathologic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) that will result in either failure to grow appropriately, respiratory complications, or apparent life-threatening events.

GERD is defined as the pathologic effects of the involuntary passage of gastric contents into the esophagus [

3]. The clinical presentation of GERD in infants and children is variable and depends on the patient's age and overall medical condition. Persistent regurgitation is the most common complaint reported by parents of children with GERD. Another presenting symptom is irritability due to pain. Painful esophagitis can be the result of the acid refluxate. Discomfort leads to crying despite consoling measures. Dysphagia develops as a result of a narrowed esophageal lumen, as well as possible esophageal dysmotility secondary to long-standing mucosal inflammation. Respiratory symptoms are commonly seen in infants and children. Chronic cough, wheezing, choking, and apnea are all symptoms that can be attributed to GER. Recurrent bronchitis or pneumonia can occur from aspiration of the refluxate.

Nissen fundoplication is a common surgical procedure for managing GERD [

4] with high success rates both in adults and children. Traditional open Nissen fundoplication is known to be associated with postoperative complications such as retching, gas bloating, dumping syndrome, and recurrence. Nowadays, most pediatric surgeons will opt for laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication for the treatment of children with GERD. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication can shorten hospital stay and reduce the risk of complications [

56]. This study aimed to compare the outcomes of laparoscopic and open Nissen fundoplication in children with GERD.

METHODS

This retrospective single center study was conducted at Seoul National University Hospital in South Korea. We reviewed the data of the patients who underwent fundoplication for GERD between January 2005 and May 2018. Children under the age of 18 years at the time of operation were only included. Patient characteristics, operation type, associated diagnosis, previous operation, neurologic impairment, postoperative complication, recurrence, and operation outcomes were investigated. Operation time, estimated blood loss, first postoperative diet, time to full feed, and hospital stay were investigated as operation outcomes. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Seoul National University Hospital (number: 1608-057-784). The requirement of informed consent was waived by the IRB due to the retrospective nature of this study. All methods used in this study were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

GERD was defined as the presence of clinical symptoms relevant to GER as defined by the Pediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux Clinical Practice Guidelines: Joint Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition [

7] or presence of positive imaging or endoscopy findings.

Symptoms were categorized as gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, extra-GI symptoms, and no symptoms. GI symptoms included recurrent regurgitation or vomiting, abdominal pain, nausea, and drooling. Extra-GI symptoms consisted of wheezing, coughing, and recurrent pneumonia.

All patients underwent diatrizoate contrast radiography and endoscopy, if the patients' condition is feasible for examinations. Some patients underwent esophageal pH monitoring.

Neurological impairment was defined as any damage to or deficiency of the nervous system. Neurological impairment was further categorized as degenerative neuromuscular disease, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, brain anomaly, genetic syndrome, cerebral palsy, or brain tumor. Other diseases not confined to the above categorizes were classified as other. The hospital stay was defined as the period from operation to discharge or to the first day of proper feeding when a patient was transferred to another department for the treatment of the underlying disease.

All patients underwent Nissen fundoplication. There was no difference between open fundoplication (OF) and laparoscopic fundoplication (LF) in terms of the detailed procedure. The only difference was the incision size and location. OF used a left subcostal incision, and LF used a 4 holes incision including an umbilical incision for the camera port. One left upper quadrant (5 mm) and one right upper quadrant incision (5 mm) were used for the working port, and another right upper quadrant incision (5 mm) was used for the retraction of the liver. After insertion of the proper sized nasogastric tube, patients were placed in the supine position for OF and in the lithotomy position for LF. The Nissen fundoplication was performed in a routine manner. Short gastric vessels were ligated in some cases. The length of wrap is determined by patient's age, height, body weight, and size of stomach. Gastropexy to the diaphragm was routinely performed. Black silk was used as the suture material for fundoplication. A range of 3–6 stitches were applied for the wrap.

SPSS version 23 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis. All continuous variables are presented as median values and the interquartile range. A normality test was first performed to test the significance of continuous variables. The Mann-Whitney U test or Student t-test was used to examine continuous data as proper. The χ2 test was used to analyze categorical data. The p-values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

1. Demographics

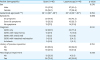

A total of 92 patients were included in this study; 50 (54.3%) were male and 42 (45.7%) were female. 48 patients underwent OF and 44 patients underwent LF. The mean age at surgery was 100 months. In total, 66 (71.7%) patients had GERD alone, 20 (21.7%) patients were diagnosed as GERD with hiatal hernia, 5 (5.4%) had GERD with another diagnosis (antral web, intestinal malrotation), 1 patient had achalasia. A history of the previous operation was present in 32 (34.8%) patients. The presence of neurological impairment was shown in 76 (82.6%) patients (

Table 1).

Table 1

Characteristics of all patients (n=92)

|

Characteristics |

Values |

|

Sex |

|

|

Male |

50 (54.3) |

|

Female |

42 (45.7) |

|

Gestational age (week+day) |

38+1±2 |

|

Symptoms |

|

|

GI symptoms |

43 (46.7) |

|

Extra-GI symptoms |

22 (23.9) |

|

No symptoms |

27 (29.3) |

|

Diagnosis |

|

|

GERD only |

66 (71.7) |

|

GERD with hiatal hernia |

20 (21.7) |

|

GERD with antral web |

3 (3.3) |

|

GERD with intestinal malrotation |

2 (2.2) |

|

Achalasia |

1 (1.1) |

|

History of previous operation |

32 (34.8) |

|

Gastrostomy |

9 |

|

Previous fundoplication |

7 |

|

Hiatal hernia repair |

4 |

|

Antral web plasty |

3 |

|

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt |

3 |

|

Others |

6 |

|

Neurological impairment |

76 (82.6) |

|

Degenerative neuromuscular disease |

19 |

|

Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy |

16 |

|

Brain anomaly |

13 |

|

Genetic syndrome |

13 |

|

Cerebral palsy |

9 |

|

Brain tumor |

2 |

|

Others |

4 |

|

Age at operation (mon) |

100±238 |

|

Concomitant gastrostomy |

63 (68.5) |

|

Operation time (min) |

123.6±53.7 |

|

Blood loss (mL) |

42.5±134 |

|

Transfusion |

7 (7.6) |

|

First postoperative diet (day) |

6.1±3.8 |

|

Time to full feed (day) |

15.2±24.6 |

|

Hospital stay (day) |

11.4±6.2 |

|

Recurrence |

22 (23.9) |

|

Follow up period (mon) |

25.3±18.9 |

|

Complications |

15 (16.3) |

|

Hiatal hernia |

8 |

|

Incisional hernia |

2 |

|

Surgical site infection |

2 |

|

Fundoplication release |

1 |

|

Ileus |

1 |

|

Right MCA occlusion |

1 |

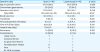

2. Comparison of demographic data between OF and LF

Patient characteristics such as sex ratio, gestational age, symptoms, diagnosis, neurological impairment, and history of the previous operation were not significantly different between the OF and LF group (

Table 2).

Table 2

Demographic characteristics according to the operation type

|

Patient demographics |

Open (n=48) |

Laparoscopy (n=44) |

p-value |

|

Sex |

|

|

0.278 |

|

Male |

23 (47.9) |

27 (61.4) |

|

Female |

25 (52.1) |

17 (38.6) |

|

Gestational age (week+day) |

38+1±3 (38+0–38+2) |

38+1±3 (38+0–38+2) |

0.784 |

|

Symptoms |

|

|

0.880 |

|

GI symptoms |

23 (47.9) |

20 (45.5) |

|

Extra-GI symptoms |

12 (25.0) |

10 (22.7) |

|

No symptoms |

13 (27.1) |

14 (31.8) |

|

Diagnosis |

|

|

0.103 |

|

GERD only |

32 (66.7) |

34 (77.3) |

|

GERD with hiatal hernia |

13 (27.1) |

7 (15.9) |

|

GERD with antral web |

3 (6.2) |

0 (0.0) |

|

GERD with intestinal malrotation |

0 (0.0) |

2 (4.5) |

|

Achalasia |

0 (0.0) |

1 (2.3) |

|

History of previous operation |

|

|

0.724 |

|

No |

30 (62.5) |

30 (68.2) |

|

Yes |

18 (37.5) |

14 (31.8) |

|

Neurological impairment |

|

|

0.083 |

|

No |

12 (25.0) |

4 (9.1) |

|

Yes |

36 (75.0) |

40 (90.9) |

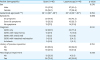

3. Comparison of operative data between OF and LF

Operative data according to operation type is described in

Table 3. Concomitant gastrostomy was performed in 63 (68.5%) patients (37 (84.1%) patients in the LF group and 26 (54.2%) patients in the OF group), with a significant difference being found between the groups (p=0.004). Patients in the LF group had a longer operative time than in the OF group (113.0±56.0 minutes in OF vs. 135.1±49.1 minutes in LF, p=0.048). When comparing operation time between the OF and LF group in patients with only GERD, there was no significant difference. The mean amount of estimated blood loss did not differ significantly between the OF group (62.3±181.4 mL) and the LF group (21.0±32.1 mL). The number of patients with intraoperative transfusion was 6 (12.5%) in the OF group and 1 (2.3%) in the LF group; however, the difference was not significant.

Table 3

Operative data according to the operation type

|

Operative data |

Open (n=48) |

Laparoscopy (n=44) |

p-value |

|

Age at operation (mon) |

101.0±266.3 |

99.7±206.8 |

0.980 |

|

Concomitant gastrostomy |

26 (54.2) |

37 (84.1) |

0.004 |

|

Operation time (min) |

113.0±56.0 |

135.1±49.1 |

0.048 |

|

Only GERD |

110.4±59.4 (n=32) |

129.5±51.8 (n=34) |

0.167 |

|

Blood loss (mL) |

62.3±181.4 |

21.0±32.1 |

0.127 |

|

Transfusion |

6 (12.5) |

1 (2.3) |

0.146 |

|

First postoperative diet (day) |

6.1±3.3 |

6.2±4.3 |

0.879 |

|

Time to full feed (day) |

16.6±32.6 |

13.6±10.8 |

0.541 |

|

Hospital stay (day) |

11.8±6.0 |

10.9±6.5 |

0.513 |

|

Recurrence |

14 (29.2) |

8 (18.2) |

0.323 |

|

Complications |

10 (20.8) |

5 (11.4) |

0.344 |

|

Hiatal hernia |

7 |

1 |

|

Incisional hernia |

1 |

1 |

|

Surgical site infection |

1 |

1 |

|

Fundoplication release |

0 |

1 |

|

Ileus |

0 |

1 |

|

Rt. MCA occlusion |

1 |

0 |

There was no significant difference in the first postoperative diet and time to full feed between the OF and LF groups. The hospital stay was 11.8±6.0 days in the OF group and 10.9±6.5 days in the LF group. Recurrence of symptoms was more frequently observed in the OF group occurring in 14 patients (29.2%) compared with 8 patients (18.2%) in the LF group, though this finding was not statistically significant. Complications were more commonly seen in the OF group, though the statistical significance is not demonstrated. Observed complications included hiatal hernia, incisional hernia, surgical site infection, fundoplication release, ileus, and right middle cerebral artery occlusion.

DISCUSSION

Pediatricians are increasingly concerned about GERD in the pediatric population, as it is a common cause of pediatric visits and referrals to pediatricians [

8]. Since 2005, many epidemiological studies of GERD have been published and systematic reviews have suggested that the prevalence of GERD is increasing worldwide [

9].

In neonates and infants, GERD can even affect growth and cause respiratory complications [

310]. Diagnostic methods of GERD included history and physical examination, esophageal pH monitoring, combined multiple intraluminal impedance, motility studies, endoscopy and biopsy, barium contrast radiography, and empiric trials of acid suppression [

3]. However, there are currently no universally accepted measures to confirm clinically relevant GERD in children, and no consensus on the indications for surgical intervention. Generally, surgical treatment is usually indicated in cases refractory to medical treatment or associated with complications. The open fundoplication procedure has been widely used in the surgical management of GERD and it has been performed for nearly 60 years. However, the approach to pediatric fundoplication has begun to shift from an open technique to a laparoscopic technique as laparoscopy has become increasingly common in pediatric surgery.

Due to scarce data regarding GERD in Korean pediatric patients, there are only a few studies discussing laparoscopic fundoplication [

11]. Only 1 article, published in Korea, was found that compared open and laparoscopic fundoplication [

12]. To evaluate the efficacy and safety of LF in the treatment of pediatric GERD, we conducted a medical chart review and compared the clinical outcomes of laparoscopic and open fundoplication in children. This study was a single-institution retrospective study to compare the outcomes of laparoscopic and open fundoplication in children with GERD in Korea.

A number of studies have examined patient characteristics and outcomes by type of fundoplication in pediatric patients. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews have concluded that LF results in decreased hospital stay, earlier resumption of enteral feeding, and less perioperative morbidity [

131415]. However, the findings of previously published randomized trials contest the result of nonrandomized studies. McHoney et al. [

16] concluded that there is no statistical difference in the length of hospital stay, pain, or rates of dysphagia or recurrence. Knatten et al. [

17] similarly conducted randomized trials and reported that there were no statistically significant differences in complication rates during the first postoperative month and hospital stay. Another randomized trial by Papandria et al. [

18] also reported similar conclusions.

The findings in this study are in keeping with the randomized studies suggesting that there is no significant difference between open fundoplication and laparoscopic fundoplication surgery in terms of hospital stay, first time to feed, recurrence, and postoperative complications.

Relatively significant time difference is found between OF and LF group in this study. Only open fundoplication was performed between 2005 and 2010, and as described above, laparoscopic approach was more commonly accepted since laparoscopy became prevalent in pediatric surgery.

The average operating time was significantly longer in the LF group. The cause of this was thought to be multifactorial such as set-up time for the laparoscopic surgery and using 5 mm instruments which may be bulky and clumsy in a small infant. Our finding that LF is more time-consuming than OF is in accordance with most previous studies, although some reports show that the length of operation is about the same for LF and OF. When limiting patients to those with GERD only, there was no difference in operation time between the groups. This might be explained by the time required to manage co-morbidities such as hiatal hernia, antral web, and intestinal malrotation.

Our results revealed that simultaneously placed gastrostomy was more frequently performed in patients who underwent LF. This is supported by the higher rate of neurological impairment in the LF group regarding the fact that children, especially those with neurologic impairment, require gastrostomy placement for feeding. Furthermore, there is a difference in trend of performing gastrostomy formation and fundoplication over time. In the past, gastrostomy formation was done first, and fundoplication was performed in addition when the gastroesophageal reflux became problem. Currently, the rate of concurrent gastrostomy formation and fundoplication is gradually increasing.

This study indicated that the patients in the LF group had a comparable incidence of postoperative complications as those in the OF group. Most individual studies comparing LF and OF in pediatric patients have similar results [

192021]. However, the lack of clear definitions of morbidity in the different studies and selection bias of patients to OF or LF limit the conclusions.

Dysphagia is one of significant complication in postoperative patients with Nissen fundoplication. In the study, dysphagia as complication was not observed. Forty-seven (51%) patients were fed via gastrostomy, and 39 (42.3%) patients had no symptoms related to oral diet.

There was no significant difference in the time to initiation of feedings and the time to full feeding. Few studies showed earlier feeding is feasible in the LF group, as a result of less pain from smaller scars and reduced bowel handling. Feeding may also be affected by the use of Stamm gastrostomy compared with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy.

Since majority of patients have neurologic impairment, these patients may show delayed gastric emptying. Information whether gastric emptying time is present is identified in cases with contrast radiography. Among patients with neurologic impairment, 25 (32.9%) patients had delayed gastric emptying. Any additional procedures during surgery were not performed without any structural problems which cause delayed gastric emptying (such as antral web). In 1 case of antral web, antral web plasty was performed simultaneously.

A limitation of this study is the retrospective nature of the data and the relatively small number of patients. Studies with a larger number of patients and a longer follow-up period are required in order to strengthen the findings that LF is an as safe and effective procedure as OF.

In conclusion, our study suggests that LF is as safe, feasible, and effective as OF for the surgical treatment of gastroesophageal reflux in children. LF has a longer operative time in general, but when considering patients with GERD only, operative time showed no significant difference between OF and LF. The LF group showed better postoperative outcomes, though statistical significance was not demonstrated. Therefore, according to our study, laparoscopic fundoplication can be safely performed in pediatric patients with GERD.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download