INTRODUCTION

Pyuria is a useful marker for assessing urinary tract infection (UTI) in the general population. The presence of pyuria is, in general, highly suggestive of UTI, especially in symptomatic patients. Pyuria seems to be common in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Sterile pyuria is considered to occur in CKD owing to chronic renal parenchymal inflammation [

12]. However, there are limited data on whether CKD increases the rate of pyuria or how pyuria in CKD should be interpreted [

2]. In fact, to our knowledge, the prevalence or characteristics of pyuria has never been investigated, especially in non-dialysis CKD patients.

Studies have addressed the diagnostic value of pyuria in CKD patients, particularly those undergoing dialysis. The prevalence of pyuria in dialysis patients has been reported to range from 31% to 72% [

123456], and the rate of documented UTI in these patients ranges from 25% to 45%. In addition, the presence of pyuria may not indicate UTI in dialysis patients [

1457]. Cellular analysis of ascites is useful for early diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in liver cirrhosis patients, and induced sputum analysis provides information on the inflammatory phenotype of airway disease [

89]. In the early 1970s, Cabaluna, et al. [

1] reported that pyuria is a common finding in hemodialysis (HD) patients that often occurs in the absence of infection. Of interest was the observation that the majority of white blood cells (WBCs) in the urine seemed to be lymphocytes. Unfortunately, no studies have explored urinary cell analysis as a follow-up to these observations of Cabaluna, et al. [

1].

We examined whether CKD patients have an increased prevalence of asymptomatic pyuria (ASP) compared with the non-CKD population. In addition, we analyzed urinary WBCs to investigate the characteristics of pyuria and the usefulness of urinary cell analysis in identifying sterile pyuria in the CKD population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population and definition

This single-center, cross-sectional study was performed at the Myongji Hospital, Gyeonggi-do, Korea. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Myongji Hospital (approval no. MJH15-024), and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

All HD patients in the dialysis center who voided at least twice every day were included, and urine was obtained before the start of dialysis between September 2016 and March 2017. In addition, stable non-dialysis CKD patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 mL/min/1.73 m

2, who visited the outpatient clinic during the study period, were included. eGFR was calculated based on the Chronic Kidney Disease-Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation [

10]. Non-dialysis CKD was divided into stages 3 (eGFR 30–59 mL/min/1.73 m

2), 4 (eGFR 15–29 mL/min/1.73 m

2), and 5 (eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m

2) according to the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes criteria [

11].

We excluded patients with evident symptoms of infection, history of antibiotic treatment in the previous month, bladder catheterization, ileal conduit, and combined acute kidney injury. Additionally, patients who did not cooperate were excluded, including those with impaired mobility from whom it was difficult to obtain reliable urine samples.

Overall, the study included 298 patients (179 males, 119 females; median age, 70.5 years [interquartile range (IQR), 57–77 years]). Among them, 70 were HD patients (51.4% males, median age 62 years [IQR 52–71 years]; dialysis vintage, 23.4±25.9 months), and 228 were non-dialysis CKD patients (62.7% males, median age 73 years [IQR 60–78 years]).

For comparison, the prevalence of pyuria in the general population was determined from the data of subjects who received comprehensive health examinations at the same hospital during the study period (total N=3,691; age, >40 years; eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2). All CKD patients included in the study, except five, were aged >40 years. The median age of the general population (2,489 males, 1,202 females) was 51 years (IQR 45–58 years).

Measurements and definitions

Clean-catch midstream urine was obtained and processed within one hour of voiding. Urinalysis and urine protein:creatinine ratio (UPCR) were examined for the entire study population. Briefly, fresh urine samples were first examined using an automated analyzer (Cobasu411, Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland), and parameters such as specific gravity, pH, WBC, and presence of urinary nitrites were recorded. Next, 10 mL of urine was centrifuged (400×

g for 5 minutes), and the sediment was resuspended in 0.5 mL of the urine supernatant for microscopic examination. Pyuria was defined as ≥5 WBCs per high-power field (HPF) by urine microscopy of centrifuged urine, which is still considered the standard method [

12] despite recent progress in automated urinalysis technology [

13]. The number of urinary WBCs were counted as 0–2, 3–5, 6–9, 10–19, 20–29, 30–49, 50–99, and ≥100. Presence of urinary nitrites was determined using urine dipstick analysis.

In this study, urine culture was performed in 86 of the 91 patients with pyuria. Urine culture was performed on MacConkey agar, blood agar, and enrichment media using the platinum loop method. Colony was identified using the Vitek system (bioMerieux, Durham, NC, USA). For urinary WBC analysis, if pyuria was confirmed, 100–200 µL of undiluted urine were cytospun onto glass slides using a Cytospin centrifuge (Cellspin, Hanil, Gimpo, Korea) (400×g for 5 minutes). Next, differential cell count was analyzed by microscopy (×400 fields) following Wright stain.

Pyuria with significant bacteriuria (≥105 colony forming units [CFU]/mL) was defined as UTI. Pyuria without significant bacteriuria was defined as sterile pyuria. Hematuria was defined as the detection of red blood cells at ≥5/HPF in microscopy, and proteinuria was defined as UPCR ≥1.

For serum chemistry, peripheral blood was collected into sterile SST vacuum tubes, centrifuged at 3,000×g for 8 minutes, and analyzed using ADVIA Chemistry XPT (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 20 (IBM Corp, NY, USA) was mainly used for statistical analyses. Data were presented as means with standard deviation (SD) or as absolute numbers with percentages. Groups were compared using the Student's t-test, Mann-Whitney U test, or χ2 test, as appropriate. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to evaluate UTI predictors and determine the role of urinary cell analysis in pyuric patients. Odds ratio (OR) was reported at 95% confidence interval (CI). Multivariate logistic regression was performed on variables with P<0.05 in univariate analysis (sex, HD, degree of pyuria, percentage of neutrophils, and presence of nitrites) and age.

The utility of the number and distribution of urinary WBCs in UTI detection was assessed by ROC curve analysis using MedCalc Software (version 18.10.2, Ostend, Belgium). Pyuria was further grouped as 6–9, 10–19, 20–49, and ≥50 WBCs/HPF. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

ASP prevalence

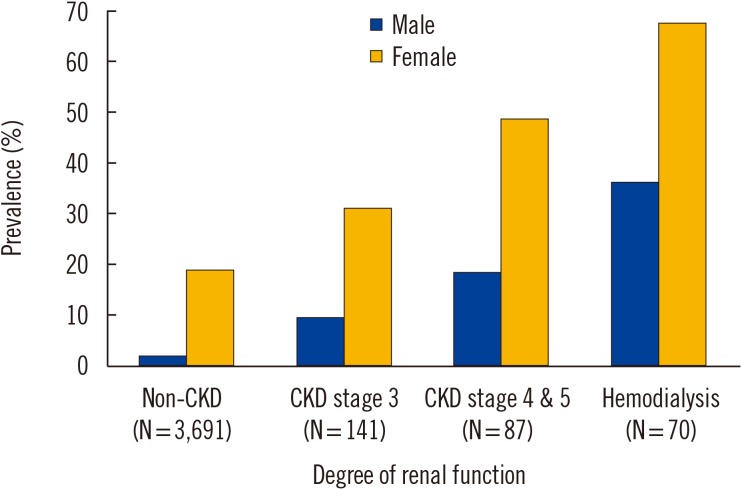

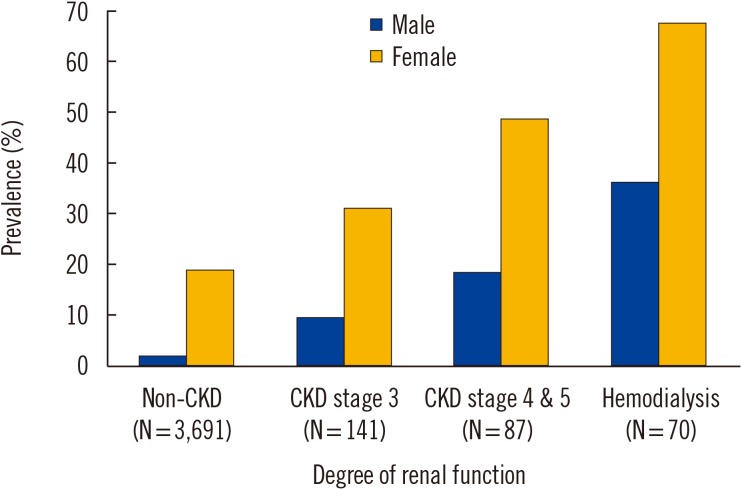

The overall ASP prevalence was 30.5% (18.4% in males and 48.7% in females). As shown in

Fig. 1, ASP prevalence increased with CKD stage. It was 51.4% (36.1% in males and 67.6% in females) in the 70 HD patients and 24.1% (14.0% in males and 41.2% in females) in the 228 non-dialysis CKD patients.

Fig. 1

The prevalence of pyuria according to the level of renal function. The prevalence of pyuria was investigated in asymptomatic CKD population. CKD was divided into HD and non-dialysis CKD; non-dialysis CKD was further classified as stages 3, 4, and 5 according to the KDIGO classification [11]. The prevalence of pyuria in the non-CKD population was estimated from regular health examination data at the study hospital and included control patients aged >40 years with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HD, hemodialysis; KDIGO, Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes.

Characteristics of pyuric patients

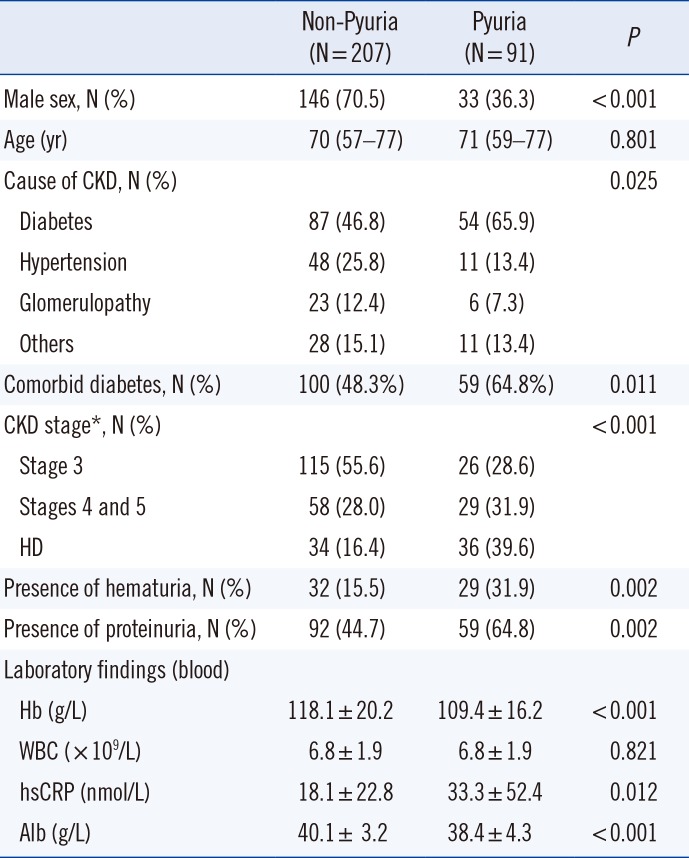

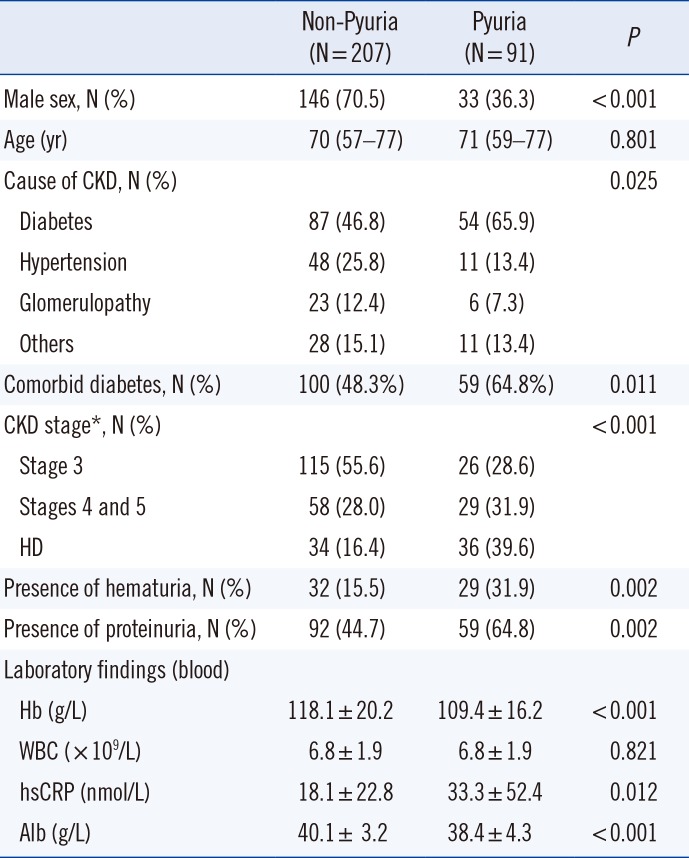

Next, we compared the baseline and clinical characteristics of pyuric and non-pyuric CKD patients. As in the general population, pyuria was more common in female than in male patients (

Table 1). The pyuric group had more advanced stages of CKD compared with the non-pyuric group. In addition, co-morbid diabetes was more common (64.8% vs. 48.3%,

P=0.011), high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs CRP) was higher, Hb and albumin (Alb) levels were lower, and hematuria and proteinuria were more common in the pyuric group than in the non-pyuric group. Median age did not differ between the pyuric and non-pyuric groups.

Table 1

Baseline and clinical characteristics of the patients with pyuria

|

Non-Pyuria (N = 207) |

Pyuria (N = 91) |

P

|

|

Male sex, N (%) |

146 (70.5) |

33 (36.3) |

< 0.001 |

|

Age (yr) |

70 (57–77) |

71 (59–77) |

0.801 |

|

Cause of CKD, N (%) |

|

|

0.025 |

|

Diabetes |

87 (46.8) |

54 (65.9) |

|

Hypertension |

48 (25.8) |

11 (13.4) |

|

Glomerulopathy |

23 (12.4) |

6 (7.3) |

|

Others |

28 (15.1) |

11 (13.4) |

|

Comorbid diabetes, N (%) |

100 (48.3%) |

59 (64.8%) |

0.011 |

|

CKD stage*, N (%) |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

Stage 3 |

115 (55.6) |

26 (28.6) |

|

Stages 4 and 5 |

58 (28.0) |

29 (31.9) |

|

HD |

34 (16.4) |

36 (39.6) |

|

Presence of hematuria, N (%) |

32 (15.5) |

29 (31.9) |

0.002 |

|

Presence of proteinuria, N (%) |

92 (44.7) |

59 (64.8) |

0.002 |

|

Laboratory findings (blood) |

|

|

|

|

Hb (g/L) |

118.1 ± 20.2 |

109.4 ± 16.2 |

< 0.001 |

|

WBC (× 109/L) |

6.8 ± 1.9 |

6.8 ± 1.9 |

0.821 |

|

hsCRP (nmol/L) |

18.1 ± 22.8 |

33.3 ± 52.4 |

0.012 |

|

Alb (g/L) |

40.1 ± 3.2 |

38.4 ± 4.3 |

< 0.001 |

Sterile pyuria and UTI

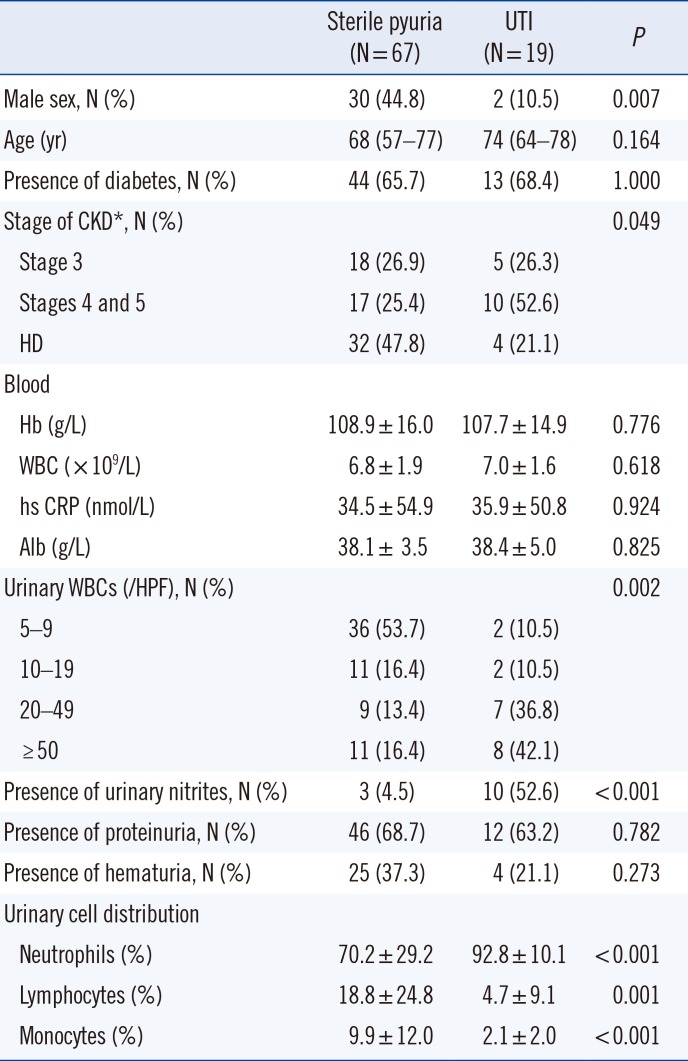

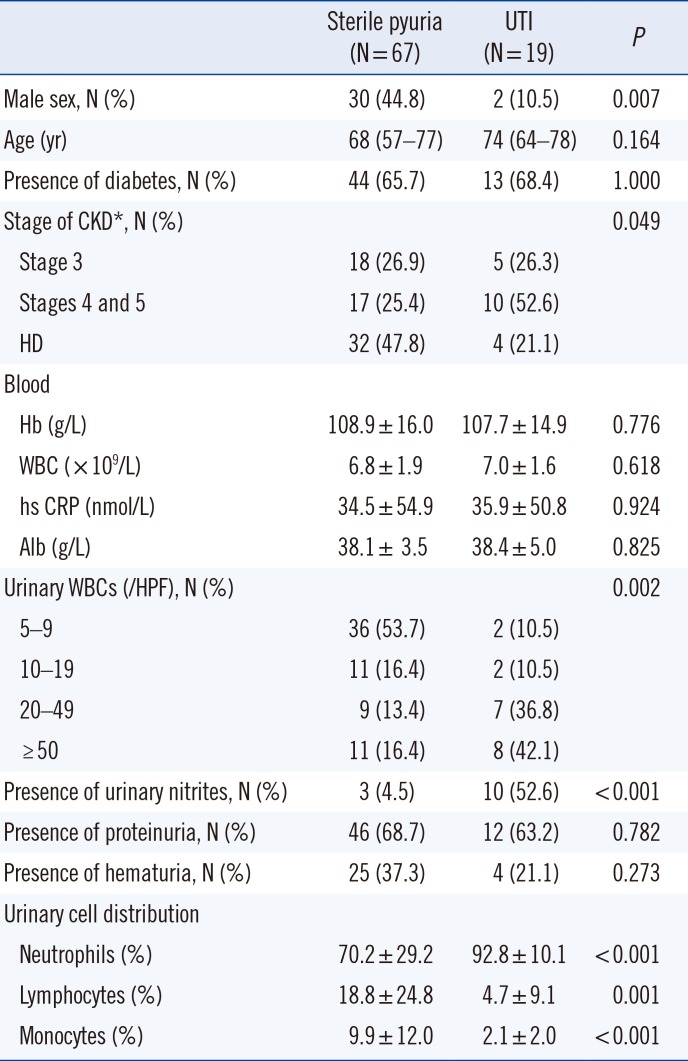

Among the 86 ASP patients who were further analyzed by urine culture, 67 (77.9%) were confirmed as sterile pyuria (88.9% of HD and 70.0% of non-dialysis CKD patients). The majority of the bacteria (78.9%) were

Escherichia coli. Next, we compared various parameters between the sterile pyuria and UTI groups. Male patients, higher stages of CKD, fewer urinary WBCs, and absence of urinary nitrites were associated with sterile pyuria (

Table 2).

Table 2

Baseline and clinical characteristics according to the presence of bacteriuria in the patients with pyuria

|

Sterile pyuria (N = 67) |

UTI (N = 19) |

P

|

|

Male sex, N (%) |

30 (44.8) |

2 (10.5) |

0.007 |

|

Age (yr) |

68 (57–77) |

74 (64–78) |

0.164 |

|

Presence of diabetes, N (%) |

44 (65.7) |

13 (68.4) |

1.000 |

|

Stage of CKD*, N (%) |

|

|

0.049 |

|

Stage 3 |

18 (26.9) |

5 (26.3) |

|

Stages 4 and 5 |

17 (25.4) |

10 (52.6) |

|

HD |

32 (47.8) |

4 (21.1) |

|

Blood |

|

|

|

|

Hb (g/L) |

108.9 ± 16.0 |

107.7 ± 14.9 |

0.776 |

|

WBC (× 109/L) |

6.8 ± 1.9 |

7.0 ± 1.6 |

0.618 |

|

hs CRP (nmol/L) |

34.5 ± 54.9 |

35.9 ± 50.8 |

0.924 |

|

Alb (g/L) |

38.1 ± 3.5 |

38.4 ± 5.0 |

0.825 |

|

Urinary WBCs (/HPF), N (%) |

|

|

0.002 |

|

5–9 |

36 (53.7) |

2 (10.5) |

|

10–19 |

11 (16.4) |

2 (10.5) |

|

20–49 |

9 (13.4) |

7 (36.8) |

|

≥ 50 |

11 (16.4) |

8 (42.1) |

|

Presence of urinary nitrites, N (%) |

3 (4.5) |

10 (52.6) |

< 0.001 |

|

Presence of proteinuria, N (%) |

46 (68.7) |

12 (63.2) |

0.782 |

|

Presence of hematuria, N (%) |

25 (37.3) |

4 (21.1) |

0.273 |

|

Urinary cell distribution |

|

|

|

|

Neutrophils (%) |

70.2 ± 29.2 |

92.8 ± 10.1 |

< 0.001 |

|

Lymphocytes (%) |

18.8 ± 24.8 |

4.7 ± 9.1 |

0.001 |

|

Monocytes (%) |

9.9 ± 12.0 |

2.1 ± 2.0 |

< 0.001 |

Contrary to our expectations that lymphocytes would be the predominant WBCs, most urinary WBCs were neutrophils, even in the sterile pyuria group. However, the percentage of neutrophils was significantly lower (70.2% vs. 92.8%, P<0.001) and the percentage of lymphocytes and monocytes was significantly higher (18.8% vs. 4.7%, P=0.001 and 9.9% vs. 2.1%, P<0.001, respectively) in sterile pyuria group compared with UTI group.

In particular, all pyuria cases with neutrophils accounting for <60% of the urinary WBCs were sterile. Furthermore, neutrophils accounted for ≥90% of the urinary WBCs in all bacteriuria cases, except two, which showed 61% and 72% neutrophils.

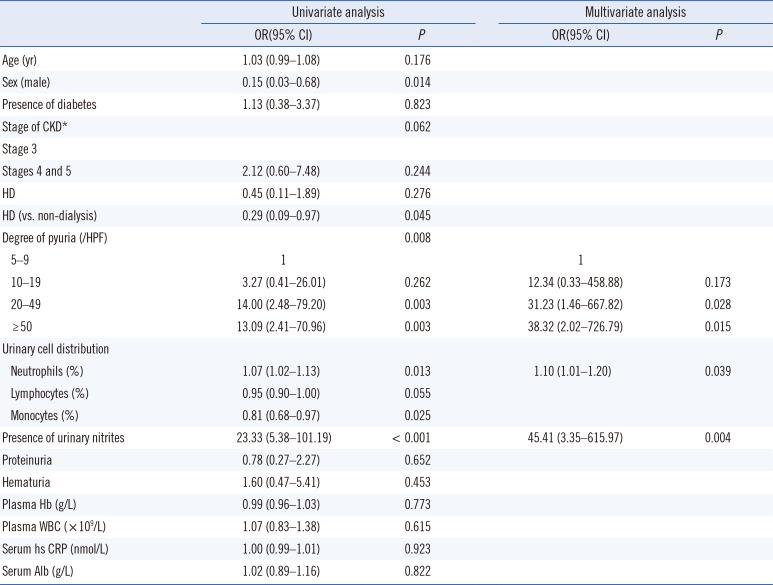

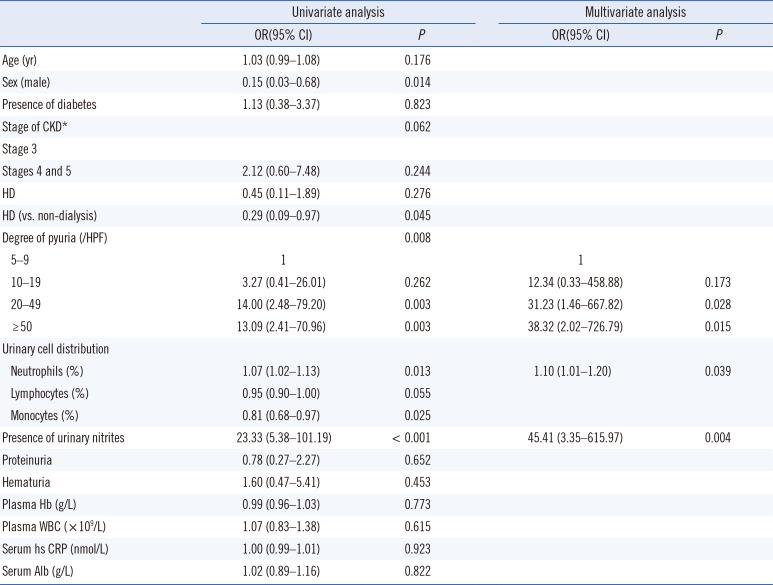

Logistic regression analysis

In univariate analysis, sex, CKD classification, the number and distribution of urinary WBCs, and presence of urinary nitrites were significant parameters for UTI (

Table 3). In multivariate analysis, the degree of pyuria, percentage of neutrophils, and presence of urinary nitrites remained independently associated with higher odds of UTI.

Table 3

Univariate and multivariate analyses for predicting UTI in patients with pyuria (N=86)

|

Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

|

OR(95% CI) |

P

|

OR(95% CI) |

P

|

|

Age (yr) |

1.03 (0.99–1.08) |

0.176 |

|

|

|

Sex (male) |

0.15 (0.03–0.68) |

0.014 |

|

|

|

Presence of diabetes |

1.13 (0.38–3.37) |

0.823 |

|

|

|

Stage of CKD*

|

|

0.062 |

|

|

|

Stage 3 |

|

|

|

|

|

Stages 4 and 5 |

2.12 (0.60–7.48) |

0.244 |

|

|

|

HD |

0.45 (0.11–1.89) |

0.276 |

|

|

|

HD (vs. non-dialysis) |

0.29 (0.09–0.97) |

0.045 |

|

|

|

Degree of pyuria (/HPF) |

|

0.008 |

|

|

|

5–9 |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

10–19 |

3.27 (0.41–26.01) |

0.262 |

12.34 (0.33–458.88) |

0.173 |

|

20–49 |

14.00 (2.48–79.20) |

0.003 |

31.23 (1.46–667.82) |

0.028 |

|

≥ 50 |

13.09 (2.41–70.96) |

0.003 |

38.32 (2.02–726.79) |

0.015 |

|

Urinary cell distribution |

|

|

|

|

|

Neutrophils (%) |

1.07 (1.02–1.13) |

0.013 |

1.10 (1.01–1.20) |

0.039 |

|

Lymphocytes (%) |

0.95 (0.90–1.00) |

0.055 |

|

|

|

Monocytes (%) |

0.81 (0.68–0.97) |

0.025 |

|

|

|

Presence of urinary nitrites |

23.33 (5.38–101.19) |

< 0.001 |

45.41 (3.35–615.97) |

0.004 |

|

Proteinuria |

0.78 (0.27–2.27) |

0.652 |

|

|

|

Hematuria |

1.60 (0.47–5.41) |

0.453 |

|

|

|

Plasma Hb (g/L) |

0.99 (0.96–1.03) |

0.773 |

|

|

|

Plasma WBC (× 109/L) |

1.07 (0.83–1.38) |

0.615 |

|

|

|

Serum hs CRP (nmol/L) |

1.00 (0.99–1.01) |

0.923 |

|

|

|

Serum Alb (g/L) |

1.02 (0.89–1.16) |

0.822 |

|

|

ROC curve

We evaluated the diagnostic performance of the number of urinary WBCs and the percentage of neutrophils in UTI identification using ROC curves (

Fig. 2).

Fig. 2

ROC curves showing the effectiveness of the number and distribution of urinary WBCs in UTI identification. The number of WBCs was analyzed at different cut-off values: ≥10, ≥20, and ≥50 WBCs/HPF.

Abbreviations: ROC, receiver operating characteristic; UTI, urinary tract infection; WBC, white blood cells; HPF, high-power field.

The number of urinary WBCs detected in UTI with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.778 (95% CI 0.661–0.870, P<0.001], and had a sensitivity of 79.0%, and a specificity of 70.2% at a cutoff value of 20/HPF. The percentage of neutrophils detected UTI with an AUC of 0.759 (95% CI 0.640–0.854, P<0.001), with a sensitivity of 88.9%, and a specificity of 62.0% at a cutoff value of 88%. The combination of both urinary factors showed increased diagnostic performance, with an AUC of 0.857 (95% CI 0.751–0.930, P<0.001).

DISCUSSION

The CKD population had higher ASP prevalence (in both male and female patients) than the non-CKD population, and it increased with CKD stage. Pyuria was more common in female patients and patients with diabetes, higher stages of CKD, proteinuria, hematuria, lower Hb and Alb, and higher CRP. Over 70% of the pyuria cases were sterile, and the majority of urinary WBCs were neutrophils, even in sterile pyuria. However, the percentage of neutrophils was significantly lower in sterile pyuria group than in UTI group (70.2% vs. 92.8%). In multivariate logistic regression analysis, the degree of pyuria, percentage of neutrophils, and presence of urinary nitrites were independently associated with sterile pyuria.

In general, CKD patients present with many comorbidities, including diabetes and neurogenic bladder that contribute to bladder stasis, thereby increasing the risk of UTI. Data on the prevalence of UTI among CKD patients is limited, although some authors have suggested that the frequency of UTI might not differ from that in the general population [

14]. In the present study, the prevalence of bacteriuria was 6.6% (1.1% in males and 14.3% in females) in the asymptomatic CKD population. We were unable to determine the prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) in the general population because the regular health examinations did not include a urine culture. A recent meta-analysis showed that diabetic patients have a higher prevalence of ASB than healthy controls (12.2% vs. 4.5%) [

15].

The diagnosis of UTI in CKD patients can be challenging. UTI symptoms are mostly related to voiding, which is particularly reduced in end-stage renal disease patients. Moreover, it has been suggested that sterile pyuria is common in CKD patients [

116]. Our results confirm that ASP is more common in the CKD than in the non-CKD population (24.1% in non-dialysis CKD and 51.4% in HD patients vs. 7.2% in the non-CKD population). A previous study reported a significantly higher ASP prevalence in both male (12.2% vs. 3.4%) and female (21.4% vs. 8.7%) diabetic patients compared with that in the non-diabetic population [

17]. In the present study, ASP was even more common in the CKD population (17.2% in males and 47.5% in females) than in the diabetic population. The factors underlying higher ASP prevalence in the CKD population, despite the relatively modest bacteriuria prevalence, are unknown and need to be further examined.

It is noteworthy that 78% of the pyuria cases were sterile. Overall, 24.2% of the asymptomatic CKD population (17.3% males and 34.5% females) showed sterile pyuria (

Supplemental Data Table S2). A previous study reported that 2.6% males and 13.9% females have sterile pyuria in the general population; these values were lower than those observed in the CKD patients in this study [

1819]. Moreover, the prevalence of sterile pyuria increased with increasing CKD stage (

Supplemental Data Table S2). Although we could not fully determine the causes of sterile pyuria in CKD patients, various possibilities exist, including leakage of cells due to tubulointerstital injury.

While it seems that pyuria is common in CKD patients and a low degree of pyuria might be sterile, optimal cut-off values for urinary WBC counts for predicting sterile pyuria in CKD patients have not yet been established. In the present study, pyuria with ≥10 WBCs/HPF was indicative of UTI with high sensitivity (89.5%) but low specificity (53.7%), while pyuria with ≥20 WBCs/HPF showed favorable sensitivity (79.0%) and specificity (70.2%) for UTI detection. The negative predictive value of urinary WBCs at a cut-off value of 10 WBCs/HPF was 94.7%. In other words, if urinary WBC count was <10 WBCs/HPF in asymptomatic CKD patients, the possibility of sterile pyuria is >90%.

In contrast to our expectation that lymphocytes would account for most of the WBCs, the majority of urinary WBCs were neutrophils, even in sterile pyuria. This finding also contrasted with that of Cabaluna, et al. [

1], although they did not report concrete differential cell count results. In this study, a low percentage of urinary neutrophils (<70%) was associated with a high probability of sterile pyuria (specificity 94.4%). The present findings are valuable as they present an additional tool for predicting sterile pyuria in pyuric CKD patients. Urinary cell analysis may help reduce unnecessary antibiotic administration or suspicion of other factors in the initial stages of asymptomatic infection. Examination of pyuria patterns through urinary cell analysis in more diverse CKD populations might provide valuable information regarding the pathobiological pathways involved in CKD.

This study had several limitations. First, despite the relatively large sample size, this was a single-center study. Second, the criteria for diagnosing UTI vary from study to study. Given that this study included an asymptomatic CKD population, UTI may actually mean ASB. However, originally, the term

urinary tract infection encompassed various clinical entities including ASB, cystitis, and pyelonephritis [

20]. Indeed, much of the literature concerning UTI does not differentiate between UTI and ASB [

20]. Considering that urinary symptoms might be vague in CKD patients, some of the significant bacteriuria accompanying pyuria in this study might have approached clinical infection. Third, the analyses were conducted using a single urine sample from each patient, rather than using a longitudinal follow-up with multiple samples [

21]. In addition, we did not examine the presence of urinary tuberculosis (TB), although it is one of the known causes of sterile pyuria. However, we considered the incidence of asymptomatic urinary TB to be low enough to dismiss the possibility.

Despite these limitations, we believe our results are important as we addressed the prevalence of sterile pyuria in an asymptomatic CKD population. To our knowledge, the prevalence of ASP or sterile pyuria has never been investigated according to CKD stage, and this is the first study to perform urinary cell analysis in pyuric CKD patients.

In conclusion, sterile pyuria is common in CKD patients. The number and distribution of urinary WBCs may be helpful for predicting sterile pyuria in CKD patients with pyuria. A large, prospective study with longitudinal follow-up may further clarify the interpretation of urinalysis in the CKD population.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download