Abstract

Background and Objectives

To measure nasal length and keystone area on sagittal plane computed tomography.

Materials and Methods

The medical records and radiographic data of 200 patients were evaluated. The length of the nasal dorsum and the bony dorsum, and the length and angle of cartilage overlap at the keystone were measured. Measurements were compared according to sex and the correlation between nasal length and patient height was analyzed.

Results

The mean length (mm) of the nasal dorsum was 46.1±3.7 in men and 41.0±2.7 in women (p<0.01). The mean length of the bony dorsum was 17.6±3.0 (38.1% of the nasal dorsal length) in men and 15.6±2.3 (37.9%) in women (p<0.01). The mean length of the cartilage overlap in the keystone area was 9.8±3.3 and 9.2±2.4 for men and women, respectively. The angle of cartilage overlap in the keystone area varied from 30.4 to 154.2 degrees. Patient height was positively correlated with both the length of the nasal dorsum and the bony dorsum (p<0.01 for both).

The external nose is formed by a framework of bony and cartilaginous structures that is covered by the skin and soft tissue envelope. Nasal length, projection, and various angles formed by the nasal skeleton in relationship with the adjoining area of the face determine the distinct anatomic features of an individual's nose.1) Therefore, a good understanding of the anatomical features of the nose has practical importance when performing rhinoplasty. Of the multitude of anatomic and anthropometric features of the external nose, nasal length and its anatomic features are the least studied.

The long axis of the external nose is composed of the bony nasal dorsum and the cartilaginous nasal dorsum.2) The lengths of the bony and cartilaginous nasal dorsa have practical importance in planning rhinoplasty. For example, osteotomy should be performed very carefully in patients who have short nasal bones.3) Accurate information regarding the length of the cartilaginous dorsal septum is important for preoperative estimation of the desired lengths of spreader grafts.4) The cartilaginous nasal dorsum commonly comprises the lower two-thirds or lower half of the nose.2) However, there is a lack of anatomic studies investigating the exact proportions of bone and cartilage constituting the nasal length, especially in Asians.

The keystone area of the nasal septum comprises the nasal bones, cartilaginous septum, perpendicular plate of the ethmoid, and upper lateral cartilages. This area is critical for maintaining the structural integrity of the nasal dorsum.5)6) In septoplasty, disruption of the junction between the septal cartilage and the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid is an important cause of saddle nose deformity. However, as there is firm attachment between the nasal bone and the septal cartilage at the keystone area, the real risk of saddling may be determined by the degree of overlap between the nasal bone and the septal cartilage, which varies considerably among patients.7) In hump nose correction, the surgeon has to reduce the bony hump and the cartilaginous hump under the resected bony hump.8) Successful correction of the nasal hump is dependent on how well the cartilaginous hump is reduced. Therefore, better understanding of the anatomy of the keystone area has critical importance in septorhinoplasty surgery.

In this study, we aimed to measure the nasal length and keystone area and their anatomical features as seen in the sagittal plane in computed tomography (CT) scans in a relatively large number of adult Korean patients.

A retrospective analysis of CT scans from 653 patients who underwent nasal surgeries, such as septoplasty, septorhinoplasty, and endoscopic sinus surgery carried out by a single surgeon at Asan Medical Center between April 2012 and December 2016 was performed. Patients who underwent a preoperative CT scan were included in the study. CT was performed on a multi-detector CT scanner: Somatom Definition (Siemens, Forchheim, Germany), LightSpeed VCT (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL), or Optima CT660 (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL). Imaging was performed with the section thickness of 2.5 mm. Patients under the age of 18 (n=24), foreigners (n=9), patients with trauma (n=115), those with congenital facial anomalies (n=9), those with a history of previous septal surgery or rhinoplasty (n=261), and those whose CT scans had insufficient quality for the evaluation of the nasal septum (n=35), were excluded. Two-hundred patients were included in the final analysis. This study was approved by our institutional review board and the requirement for informed consent from patients was waived.

Demographic, clinical, operative, and radiological data were carefully reviewed. For each patient, a sagittal view that best represented all components of the keystone area was selected. The following measurements were then recorded: nasal dorsal length, bony dorsal length, length of cartilage overlap, and angle of cartilage insertion (Fig. 1). The nasal dorsal length was measured from the sellion to the pronasale. The bony dorsal length was measured from the nasion to the caudal end of the nasal bone. The length of cartilage overlap was measured as the distance the septal cartilage extended under the nasal bone to the caudal end of the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid. The angle of cartilage insertion was defined as the angle formed by the nasal bone, cartilaginous septum, and perpendicular plate of the ethmoid. Measurements were obtained using Picture Archiving and Communications System (Multivox; Seoul, Korea).

In order to study the effects of sex and height on nasal anatomy, the measurements were compared according to sex using the Student's t-test and multiple regression analysis, and the correlation between nasal length and the patient's height was analyzed using Spearman correlation analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using IBS SPSS software version 23.0 (IBM Corp.; Armonk, NY).

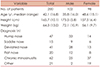

The 200 patients comprised 98 women and 102 men (median age, 42 years; range, 18–81 years). The average height of the male patients was 173.5±5.8 cm and that of the female patients was 157.5±6.4 cm. Postoperative diagnosis of the patients indicated that there were 47 cases of hump nose, 15 cases of saddle nose, 41 cases of deviated nose, 20 cases of flat nose, 62 cases of chronic rhinosinusitis, and 21 other cases, such as natural killer/T-cell lymphoma (Table 1). These diagnoses were not mutually exclusive.

The mean length of the nasal dorsum was 46.1±3.7 mm for male patients and 41.0±2.7 mm for female patients (p<0.01). The mean length of the bony dorsum was 17.6±3.0 mm (38.1% of the nasal dorsal length) for male patients and 15.6±2.3 mm (37.9%) for female patients (p<0.01). The mean length of the cartilaginous dorsum was 28.5±2.7 mm (61.9%) for male patients and 25.5±2.1 mm (62.1%) for female patients (p<0.01). The mean lengths of the cartilage overlap at the keystone area were 9.8±3.3 mm and 9.2±2.4 mm for male and female patients, respectively (p= 0.13). The angle formed by the nasal bone, the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid, and the septal cartilage at the keystone area varied from 30.4 degrees to 154.2 degrees. The average angle was 81.8±24.3 degrees for male patients and 80.0±26.0 degrees for female patients (p=0.61) (Table 2).

We analyzed the correlation between the patient's height and nasal lengths. Nasal dorsal length (φ=0.56, p<0.01) and bony dorsal length both had positive correlations (φ=0.48, p<0.01) with the patient's height. The length of cartilage overlap also had a positive correlation with patient height (φ=0.15, p=0.03) (Fig. 2). The differences in nasal lengths between male and female patients were still valid when adjusted for their height.

We also analyzed the correlation between the patient's age and the length of cartilage overlap. The two variables showed negative correlation (φ=−0.26, p<0.01) when adjusted for the patient's height.

We were able to obtain preoperative facial photographs in 135 of the 200 patients. We categorized each of the 135 patients based on whether they had a hump, saddle nose deformity, deviation, or a flat nose. We then compared the nasal lengths and angle of cartilage insertion between the different groups. Patients with hump nose had longer nasal dorsal lengths (p<0.01), longer bony dorsal lengths (p<0.01), and smaller angles of cartilage insertion (p<0.01) at the keystone area than those without hump nose. Patients with flat nose had shorter nasal dorsal lengths (p<0.01) and shorter bony dorsal lengths (p<0.01) than those without flat nose (Table 3).

In the present study, which was carried out in Korean adults, the mean length of the nasal dorsum was 43.6±4.1 mm and the mean length of the cartilage overlap at the keystone area was 9.5±2.9 mm. The cartilaginous dorsum constitutes about 62% of the nasal dorsal length. Male patients had significantly longer nasal lengths than female patients did. In addition, patient's height had a positive correlation with nasal length.

Anatomical features of the external nose differ among individuals from different ethnicities. Anthropometric measurements were performed in 110 healthy Turkish men by Tuncel et al. The authors found the mean nasal bridge length to be 57.35±0.26 mm9) which was significantly longer than the nasal length obtained in our study group. The difference in nasal lengths found in the two studies illustrates the well-described racial and ethnic differences in the external nose.10)11) Li et al. analyzed the external nose in 900 Han Chinese adults. They found the mean nasal length to be 48.34±4.71 mm in women and 48.43±4.43 mm in men, which is a similar outcome to that of our study (43.6 mm). However, the authors of the above study found no differences between men and women.12) The differences between Chinese and Korean noses may be due to the different methodologies used in the two studies, or may reflect actual differences in nasal length between the two races.

The length of the cartilaginous dorsum was 28.5±2.7 mm (61.9%) in men and 25.5±2.1 mm (62.1%) in women in our study. Carr et al. calculated the mean ratio of nasal cartilaginous length to overall dorsal length in Caucasians to be 0.63, which is a similar finding to that in our study.7) Godley et al., in a study using 60 adult cadavers, reported that the length of the cartilaginous dorsum was 21±5 mm on average. They found that this length was shorter in women by 5±4 mm.13) Kim et al., in their study reviewing 280 patients who underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the nasal septum, found that the mean cartilage dorsal length was 26±4 mm, and that there were no significant differences between sexes.14) These findings are contradictory to ours. Based on the above results, we may conclude that in Korean individuals, the cartilaginous dorsum constitutes about 60% of the whole nasal length.

During surgery, surgeons often encounter variations in the patterns of cartilage overlap at the keystone area. We can perform septal cartilage resections, osteotomies, or hump resection without compromising the integrity of the keystone area in some patients, while this is not possible in other patients. We can speculate that the lengths and angles formed by the structural components of the keystone area are key components in the maintenance of strong support for the nasal septum. However, few reports have described this relationship to date. We found that the overlapping length of the cartilage with the nasal bone at the keystone area was 9.5±2.9 mm. A radiologic study of 91 Caucasian noses by Carr et al. revealed that the mean overall length of the keystone area was 9.04 mm (range, 0–23 mm). The authors of that study proposed that a keystone length of less than 5 mm is associated with an increased risk of supratip depression, although this length was somewhat arbitrary.7) Despite obvious differences in overall nasal length between Caucasians and Asians, our results indicate that there is no considerable difference in keystone area length between the two ethnic groups. Other studies have reported shorter mean keystone areas than that reported here. The part of the nasal septal cartilage overlapping the nasal bone was reported to be 7±2 mm long on average in a study by Kim et al.14) In a study by Godley et al., the length of the cartilage overlap was 4±2 mm on average.13) The study by Kim et al. was conducted using MR sections, while the study by Godley et al. was conducted using cadavers. The discrepancy between the two studies may thus be due to differences in methodology. In our study, wherein we analyzed the midline sagittal view in CT scans to measure the maximal overlap of the cartilage and bone at the keystone area, we are unable to measure the overlap between the upper lateral cartilages and the nasal bone. In another cadaveric study of 18 adult Korean noses, Kim et al. stated that the mean overlap distance between the nasal bones and the upper lateral cartilages in Koreans was 7 mm (range, 4–10 mm).15)

In our study, the angle formed by the nasal bone, the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid, and the septal cartilage at the keystone area varied from 30.4 degrees to 154.2 degrees, and had an average value of 80.9±25.1 degrees. In the study by Godley et al., this angle measured 150±12 degrees. The authors of that study suggested that dorsal grafts should be designed at a 150-degree angle to fit securely and properly under the nasal bones.13) Few reports have described the relationship between this angle of insertion and the stability of the keystone area to date. However, we may speculate that more acute angles of insertion provide stronger support for the L-strut than obtuse angles of insertion. The cartilage would thus be secured more tightly within an acute bony framework provided by the nasal bone and the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid.

Our findings indicate that patients with hump nose have longer nasal dorsal lengths and bony dorsal lengths, and smaller angles of cartilage insertion. Patients with hump nose also had longer bony portions (40% vs. 37%). This implies that hump nose is a manifestation of excessive nasal growth. We also found that patients with flat nose have shorter nasal dorsal lengths and bony dorsal lengths. However, there were no significant differences in nasal length or angle between patients with deviated nose and those with saddle nose deformity. This is probably because deviation and saddle nose deformity are usually acquired deformities and especially occur after trauma or surgical manipulation. We excluded these patients from our study. This left us with only 14 patients with saddle nose deformity and 41 patients with deviated nose. These patients were small in number, unsuitable for statistical analysis.

The strength of our study lies in the fact that it includes a relatively large number of Korean patients, whereas existing literature focuses mainly on Caucasian noses. Previous studies have been conducted on cadavers13)15) or using radiographs of patients with non-sinonasal etiologies, i.e., CT scans of patients undergoing transsphenoidal pituitary surgery7) or brain MRI.14) However, we studied sagittal scans of patients undergoing nasal surgery, which better reflect the situation encountered by rhinologists on the operating table. Here we admit the limitation of radiologic study that the sagittal view of a CT scan can only represent a single dimension of the keystone area. However, the keystone area is a 3-dimensional anatomical concept consisting of the width of the septum, the width of the nasal bones, and the width of the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid, all of which contribute significantly to the stability of the nose, cannot be thoroughly assessed through this methodology.

CT scanning places patients at risk for radiation exposure. Therefore, not all patients should undergo scanning prior to septal surgery alone, as not all patients require the procedure. However, in cases where CT scanning is appropriate, such as in patients with inflammation of the paranasal sinuses or tumors, the septum should also be thoroughly evaluated. Patients expected to have weaker keystone areas would benefit from a more careful dissection and extra procedures to secure the stability of this area. Further studies are required to define the relationships between the components of the keystone area and the risk of supratip depression. Future studies should also be carried out to determine whether it would be possible to suggest a certain length or angle as a cut-off value.

Our study, which was carried out in Korean patients, revealed that men had longer noses than women did, and that there was a positive correlation between patient height and nasal length. The cartilaginous dorsum constitutes over half of the whole nasal length and extends under the nasal bone by about 9.5 mm. This finding may be useful in better understanding the anatomical features of Asian noses.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Measurement of nasal lengths and angle. A: Nasal dorsal length (from the radix to the tip). B: bony dorsal length (from the nasion to the caudal end of the nasal bone). C: length of cartilage overlap (from the caudal end of nasal bone to the bony-cartilaginous junction of the septal cartilage and the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid). D: angle of cartilage insertion (angle formed by the nasal bone, cartilaginous septum, and perpendicular plate of the ethmoid).

Fig. 2

Correlations between (A) nasal dorsal length, (B) bony dorsal length, and (C) length of cartilage insertion, and the patient's height.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by International Scientific Partnership Program grant 007 from King Saud University.

References

1. Rohrich RJ, Adams WP, Ahmad J, Gunter J. Dallas rhinoplasty: nasal surgery by the masters. CRC Press;2014.

2. Saharia PS, Deepti S. Septoplasty can Change the Shape of the Nose. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013; 65(Suppl 2):220–225.

3. Lam SM, Williams EF 3rd. Anatomic considerations in aesthetic rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg. 2002; 18(4):209–214.

4. Teymoortash A, Fasunla JA, Sazgar AA. The value of spreader grafts in rhinoplasty: a critical review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012; 269(5):1411–1416.

5. Kim YD. Septoplasty and turbinoplasty; current concept and technique. Journal of Rhinology. 2012; 19(1):19–28.

6. Song SH, Nam WH, Kim JS. Anchoring suture for correction of septal deviation. Journal of Rhinology. 2006; 13(1):18–21.

7. Carr S, Twigg V, Mirza S. Radiological study of the anatomy of the keystone area of the nasal septum using computed tomography to aid septal surgery. Clin Otolaryngol. 2016; 41(4):317–320.

8. Palhazi P, Daniel RK, Kosins AM. The osseocartilaginous vault of the nose: anatomy and surgical observations. Aesthet Surg J. 2015; 35(3):242–251.

9. Tuncel U, Turan A, Kostakoglu N. Digital anthropometric shape analysis of 110 rhinoplasty patients in the Black Sea Region in Turkey. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2013; 41(2):98–102.

10. Leong SC, White PS. A comparison of aesthetic proportions between the Oriental and Caucasian nose. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2004; 29(6):672–676.

11. Wang JH, Jang YJ, Park SK, Lee BJ. Measurement of aesthetic proportions in the profile view of Koreans. Ann Plast Surg. 2009; 62(2):109–113.

12. Li KZ, Guo S, Sun Q, Jin SF, Zhang X, Xiao M, et al. Anthropometric nasal analysis of Han Chinese young adults. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2014; 42(2):153–158.

13. Godley FA. Nasal septal anatomy and its importance in septal reconstruction. Ear Nose Throat J. 1997; 76(8):498–501.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download