Abstract

Hypomelanosis of Ito (HI) is a neurocutaneous disorder, also known as incontinentia pigmenti achromians. HI has been associated with chromosomal abnormalities, especially mosaicism. Herein, we report a case of HI with multiple congenital anomalies. A 2-month-old girl presented with multiple linear and whorling hypopigmentation on the face, trunk, and both extremities and patch alopecia on the scalp. Moreover, she had conical teeth, aniridia of the both eyes, and multiple musculoskeletal problems, including syndactyly and coccyx deviation. Cytogenetic analysis on peripheral blood was normal 46, XX, and no mutation was found in IKBKG gene test.

Hypomelanosis of Ito (HI) was first described in 1952 by Ito1, a Japanese dermatologist. He reported a female patient with multiple depigmented whorls and streaks and described it as “incontinentia pigmenti achromians,” because the distribution of the skin lesion was similar to that of incontinentia pigmenti (IP). Whereas IP is known to be associated with NF-κB essential modulator IKBKG gene mutation, HI develops sporadically and has no causative gene234. Several studies on cytogenetic investigation have been reported, and various kinds of chromosomal abnormalities and mosaicism have been found in patients with HI25678. Although some cases of HI have been reported in Korea91011, there are few reports on chromosomal analysis and associated comorbidities, especially multiple congenital anomalies. Herein, we report a case of HI with multiple congenital anomalies in a patient without chromosomal mosaicism of peripheral blood lymphocytes.

A 2-month-old girl was referred to the Department of Dermatology for the evaluation of extending hypopigmented skin lesions. At birth, she had multiple linear erythematous erosive skin defects, which became linear, hypopigmented patches with irregular border on the face, scalp, trunk, and both extremities (Fig. 1). We received the patient's consent form about publishing all photographic materials. The patient had a history of intrauterine growth retardation as a prenatal problem. There was no specific family history, and her two siblings were normal.

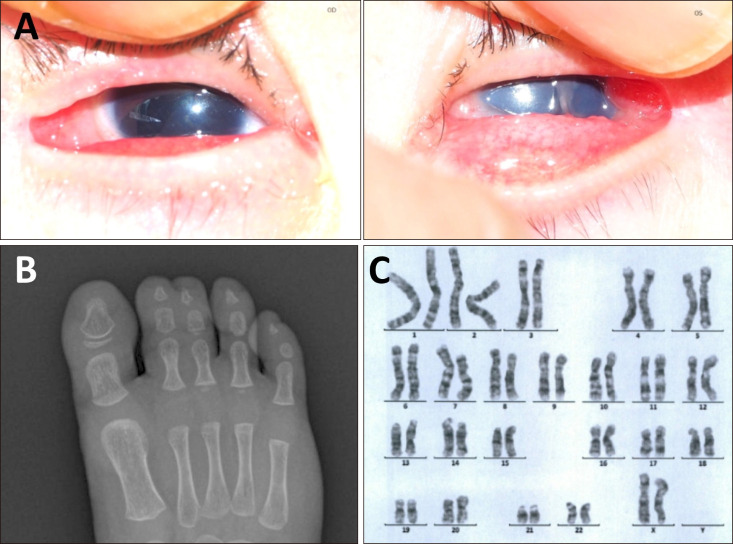

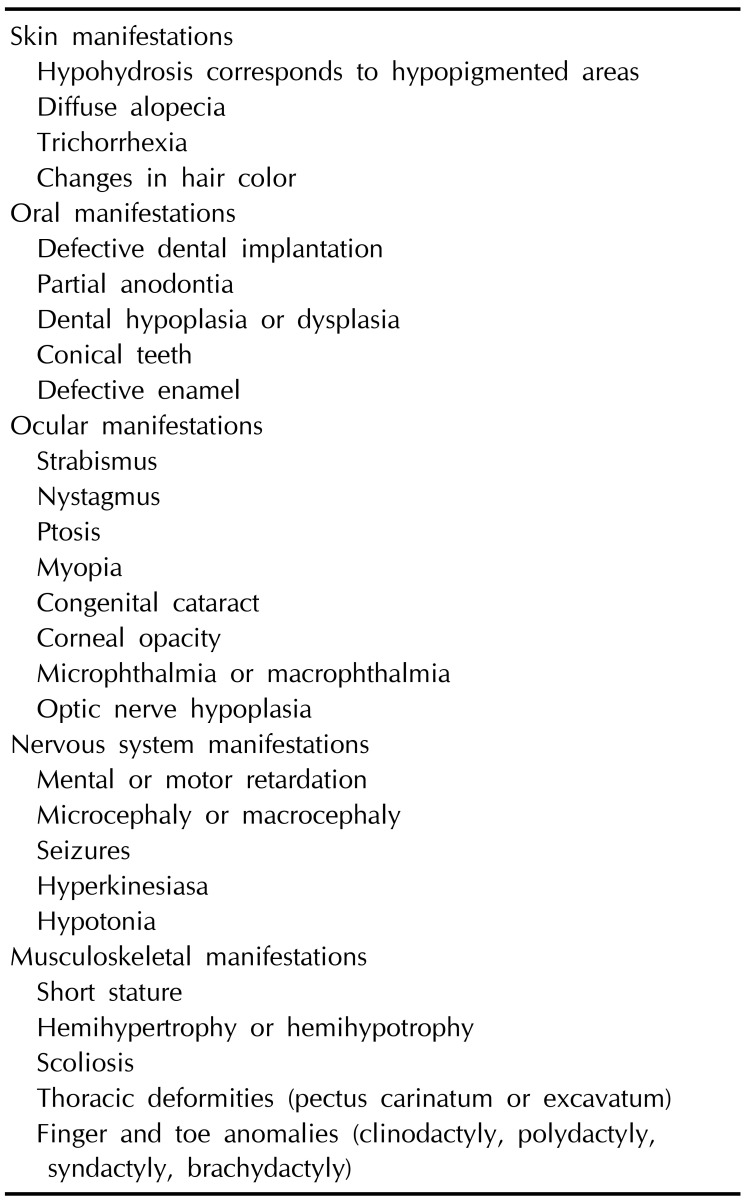

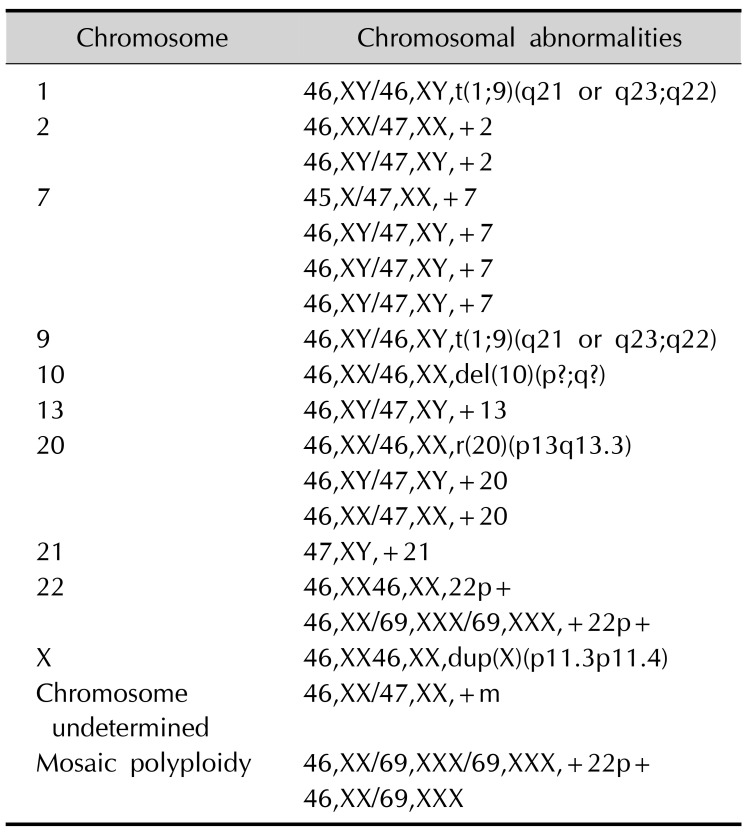

The patient also presented multiple congenital anomalies. Physical examination revealed patchy alopecia of the scalp, hypoplastic nails, and irregular gingiva with conical teeth. Ocular examination showed bilateral aniridia, moderate to severe microphthalmia, and unilateral corneal central opacity of the left eye (Fig. 2A). The retinal vessels of both eyes were uncertain on fundus examination. Musculoskeletal examination revealed syndactyly of toes (Fig. 2B), hypoplasia and clinodactyly of fingers, and coccyx deviation. Chromosomal analysis on peripheral blood lymphocytes showed normal karyotype (46, XX) (Fig. 2C), and no mutation was found in IKBKG gene test. Therefore, the patient was diagnosed with HI with multiple congenital anomalies.

To manage the associated musculoskeletal anomalies, the patient was referred to the Department of Pediatric Orthopedic Surgery and underwent surgical treatment of toe syndactyly. For proper management of the other anomalies, she had been undergoing pediatric, ophthalmologic, and dermatological regular check-up.

HI is a neurocutaneous disorder, also known as IP achromians. The characteristic cutaneous manifestation is the multiple whorl-like or linear hypopigmentation along Blaschko's line. The pigmentary lesions are recognized at birth or within few years, and do not require special treatment in most cases121314. Some patients also have extracutaneous involvements including neurological, musculoskeletal, ocular, and other systemic abnormalities (Table 1)812141516.

The patient in this case was diagnosed as HI by characteristic cutaneous features and the associated anomalies without any family history. The diagnostic criteria for HI were first suggested by Ruiz-Maldonado et al.15 in 1992 after reviewing 94 cases previously reported in literature. According to the diagnostic criteria, this patient could be diagnosed as “definitive” HI by satisfying the sine qua non criterion, one major criterion, and more than two minor criteria.

HI is considered as a cutaneous manifestation of mosaicism, especially as “pigmentary mosaicism” rather than a specific diagnosis. Previous studies have reported that various kinds of cytogenetic abnormalities were found in patients with HI25678. A genetic study reported that chromosomal abnormalities in pigmentary mosaicism, including HI, largely overlap with pigmentary gene loci, explaining how disparate mosaicism might manifest as a common phenotype2.

Cutaneous mosaicism along Blaschko's lines could be attributed to chromosomal or functional mosaicism. A research showed that cytogenetic analysis on epidermal keratinocytes revealed mosaicism in two patients with HI although mosaicism was not detected in peripheral blood lymphocytes and dermal fibroblasts17. According to this result, the linear hypomelanotic lesions along Blaschko's lines in HI may develop as a consequence of mosaicism of epidermal cells. Thus, the pattern of Blaschko's lines in HI may result from the migration and proliferation of epidermal cells during embryogenesis17. In our case, the cytogenetic analysis on peripheral blood lymphocytes was normal 46, XX. This can be explained by the fact that either peripheral blood sample may not include the involved cells despite of the presence of chromosomal mosaicism, or the cytogenetic abnormalities were submicroscopic1718.

HI differs from IP and linear and whorled nevoid hypermelanosis (LWNH) which are pigmentary disorders distributed along the lines of Blaschko. IP is an X-linked dominant disorder, and the cells expressing mutated X chromosome are eliminated perinatally, resulting in the characteristic four cutaneous stages of IP3. Due to lyonization (X-chromosome inactivation), individuals with IP have skin lesions following the Blaschko's lines, representing single clones of cells1920. Unlike IP, HI and LWNH generally occur sporadically and are rather considered as nonspecific pigmentary disorders caused by genetic mosaicism2212223.

Skin pigmentation in HI and LWNH may differ whether the mutated cell line contains more or less melanosomes than the normal cell line23. Thus, HI and LWNH could be grouped by using a term ‘pigmentary mosaicism’2.

Interestingly, our patient showed linear erythematous erosive skin defects at birth, even though the classical blistering and verrucous lesions or hyperpigmentation were absent. The preceding inflammatory skin lesion is not a feature of HI, while most cases of IP have the characteristic inflammatory and verrucous stages before the hyperpigmentation. In the literature, two patients with chromosomal mosaicism, 45,X/46,X,+r(X) and 46,X,t(X;13)(p11.21; q12.3), were described as having erythematous eruption followed by hyperpigmentation and were diagnosed as IP242526. Considering that IP is an X-linked genetic disorder, it would be more appropriate to diagnose them as HI rather than IP. Therefore, it is likely that a preceding inflammatory lesion may occur in HI depending on the type of genetic mosaicism, although the inflammatory skin lesion may mislead to diagnose some cases as IP. In our case, the genetic analysis for excluding IP found no mutations in the IKBKG gene and the chromosomal analysis on peripheral blood was normal. Thus, further chromosomal analysis on skin cells might help to reveal the hidden chromosomal mosaicism or other genetic abnormalities.

Finally, our patient presented multiple congenital anomalies, which involve the hair, nails, eyes, teeth, and musculoskeletal system. Except for one case of Turner syndrome27, most of the HI cases in Korea presented only characteristic hypopigmented skin lesions. HI with multiple congenital anomalies has not been reported in Korea so far, and there are limited data about HI-associated anomalies in Korea, considering 74% patients had one or more congenital anomalies in a clinical review of 73 cases in Japan12.

A variety of cytogenetic abnormalities in almost all chromosomes has been reported in pigmentary mosaicism, and have already been described by Taibjee et al.2 in 2004. Recently reported cytogenetic abnormalities, such as a balanced reciprocal translocation between chromosome 1 and 9, trisomy 2, ring chromosome 20, and trisomy 21 are summarized in Table 211. As almost all chromosomes have been affected, there could be a great variety of congenital anomalies in HI2. Further investigation into the association between chromosomal abnormalities and systemic manifestations in HI may contribute to the discovery and understanding of the hidden function of genes in specific loci.

References

1. Ito M. Studies of melanin. XI. Incontinentia pigmenti achromians: a singular case of nevus depigmentosus systematicus bilateralis. Tokoku J Exp Med. 1952; 55(Suppl):S57–S59.

2. Taibjee SM, Bennett DC, Moss C. Abnormal pigmentation in hypomelanosis of Ito and pigmentary mosaicism: the role of pigmentary genes. Br J Dermatol. 2004; 151:269–282. PMID: 15327534.

3. Smahi A, Courtois G, Vabres P, Yamaoka S, Heuertz S, Munnich A, et al. Genomic rearrangement in NEMO impairs NF-kappaB activation and is a cause of incontinentia pigmenti. The International Incontinentia Pigmenti (IP) Consortium. Nature. 2000; 405:466–472. PMID: 10839543.

4. Happle R. Incontinentia pigmenti versus hypomelanosis of Ito: the whys and wherefores of a confusing issue. Am J Med Genet. 1998; 79:64–65. PMID: 9738871.

5. Küster W, König A. Hypomelanosis of Ito: no entity, but a cutaneous sign of mosaicism. Am J Med Genet. 1999; 85:346–350. PMID: 10398257.

6. Pavone V, Signorelli SS, Praticò AD, Corsello G, Savasta S, Falsaperla R, et al. Total hemi-overgrowth in pigmentary mosaicism of the (hypomelanosis of) Ito type: eight case reports. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016; 95:e2705. PMID: 26962770.

7. Donnai D, Read AP, McKeown C, Andrews T. Hypomela nosis of Ito: a manifestation of mosaicism or chimerism. J Med Genet. 1988; 25:809–818. PMID: 3236362.

8. Sybert VP. Hypomelanosis of Ito: a description, not a diagnosis. J Invest Dermatol. 1994; 103(5 Suppl):141S–143S. PMID: 7963677.

9. Hwang SW, Cho KJ, Oh DJ, Lee D, Kim JW, Park SW. Two pilosebaceous cysts with apocrine hidrocystoma in one biopsy site: a spectrum of the same disease process? Ann Dermatol. 2008; 20:11–13. PMID: 27303150.

10. Yang JS, Bae EY, Park YM, Kim HO, Kim CW. A case of linear and whorled nevoid hypermelanosis associated with congenital hemihypertrophy. Korean J Dermatol. 2003; 41:1564–1567.

11. Jang YH, Kim HJ, Na GY, Lee WJ, Kim DW, Jun JB. A case of hypomelanosis of Ito with diploid/triploid mosaicism. Korean J Dermatol. 2005; 43:1085–1088.

12. Takematsu H, Sato S, Igarashi M, Seiji M. Incontinentia pigmenti achromians (Ito). Arch Dermatol. 1983; 119:391–395. PMID: 6847218.

13. Ruggieri M, Pavone L. Hypomelanosis of Ito: clinical syndrome or just phenotype? J Child Neurol. 2000; 15:635–644. PMID: 11063076.

14. Pascual-Castroviejo I, Ruggieri M. Hypomelanosis of Ito and related disorders (pigmentary mosaicism). In : Ruggieri M, Pascual-Castroviejo I, Di Rocco C, editors. Neurocutaneous disorders phakomatoses and hamartoneoplastic syndromes. Vienna: Springer Vienna;2008. p. 363–385.

15. Ruiz-Maldonado R, Toussaint S, Tamayo L, Laterza A, del Castillo V. Hypomelanosis of Ito: diagnostic criteria and report of 41 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1992; 9:1–10. PMID: 1574469.

16. Glover MT, Brett EM, Atherton DJ. Hypomelanosis of Ito: spectrum of the disease. J Pediatr. 1989; 115:75–80. PMID: 2738798.

17. Moss C, Larkins S, Stacey M, Blight A, Farndon PA, Davison EV. Epidermal mosaicism and Blaschko's lines. J Med Genet. 1993; 30:752–755. PMID: 8411070.

18. Happle R. Mosaicism in human skin. Understanding the patterns and mechanisms. Arch Dermatol. 1993; 129:1460–1470. PMID: 8239703.

21. Kalter DC, Griffiths WA, Atherton DJ. Linear and whorled nevoid hypermelanosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988; 19:1037–1044. PMID: 3204178.

22. Nehal KS, Pebenito R, Orlow SJ. Analysis of 54 cases of hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation along the lines of Blaschko. Arch Dermatol. 1996; 132:1167–1170. PMID: 8859026.

23. Di Lernia V. Linear and whorled hypermelanosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007; 24:205–210. PMID: 17542865.

24. de Grouchy J, Turleau C, Doussau de Bazignan M, Maroteaux P, Thibaud D. Incontinentia pigmenti (IP) and r(X). Tentative mapping of the IP locus to the X juxtacentromeric region. Ann Genet. 1985; 28:86–89. PMID: 3876068.

25. Kajii T, Tsukahara M, Fukushima Y, Hata A, Matsuo K, Kuroki Y. Translocation (X;13)(p11.21;q12.3) in a girl with incontinentia pigmenti and bilateral retinoblastoma. Ann Genet. 1985; 28:219–223. PMID: 3879432.

26. Sybert VP. Incontinentia pigmenti nomenclature. Am J Hum Genet. 1994; 55:209–211. PMID: 8023849.

Fig. 1

Linear, hypopigmented patches with irregular border on the face, scalp, trunk, and both extremities.

Fig. 2

(A) Ocular examination showed bilateral aniridia and unilateral corneal central opacity of the left eye. (B) Syndactyly of the left 2nd and 3rd toes was corrected surgically. (C) Cytogenetic analysis on peripheral blood lymphocytes was normal 46, XX.

Table 1

Table 2

Recently reported chromosomal abnormalities in hypomelanosis of Ito*

*Chromosomal abnormalities in pigmentary mosaicism have already been described in an article by Taibjee et al.2 in 2004, and we summarized chromosomal abnormalities in hypomelanosis of Ito reported after that.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download