METHODS

Data sampling

This study was based on the fifth KWCS, conducted by the Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency. The study used a multistage random sampling approach. The enumeration districts in the 2010 Population and Housing Census were used for sampling. Data were gathered via a questionnaire and face-to-face interviews at participants' homes. The survey gathered comprehensive information on working conditions to identify workforce changes as well as the quality of each participant's work and life. The survey was performed in 2017 and targeted the economically active population, aged 15 and over, who were either paid workers or self-employed at the time of interview. The survey data were weighted; the sample distribution by region, locality, gender, age, economic activity, and occupational status was identical to that of the overall economically active population at the time of the survey. We excluded certain participants: unpaid workers, military personnel and men workers, and those who had not fully completed the questionnaires. Finally, a total of 23,128 workers (11,007 men, 12,121 women) were included in the study.

Fig. 1 provides a schematic diagram depicting the sample population.

| Fig. 1

Schematic diagram depicting study population.

KWCS = Korean Working Conditions Survey.

|

Customer-facing job

Two questionnaire items were used to evaluate the extent of emotional labor performed by individuals at their respective workplaces. The first questionnaire item was “I manage upset customers or patients.” Responses to this item were regrouped into three categories: those who responded as either “always” or “almost always” were regrouped as the “Always” group; those spending 25% to 75% of their duty hours in managing customers were regrouped as the “Sometimes” group; and those who responded as either “almost never” or “never” were regrouped as the “Rarely” group. The second questionnaire item was “I have to suppress my emotions at work,” for which the responses were also regrouped into three categories: those who responded as “always” or “almost always” were added to the “Always” group; those who responded as “sometimes” were added to the “Sometimes” group; and those who responded as “almost never” or “never” were added to the “Rarely” group. The two identified forms of emotional labor were labeled as “Engaging with angry clients” and “Suppressing one's emotions at work.”

Subjective symptoms of depression and anxiety

Two questionnaire items were used to identify subjective symptoms of depression and anxiety. To the question “Have you suffered from the following health problems during the past 12 months?” with the options of “depression” and “anxiety,” the two response options provided were “ever” and “never.” Participants who responded as “ever” (regrouped as “yes”) were considered to have experienced the subjective symptoms of either depression or anxiety, and those who responded as “never” (regrouped as “no”) were considered to have not experienced either issue in the past.

Sleep disturbance

To identify sleep disturbance, we used a question regarding sleep quality: “How often have you had the following problems with sleep in the last 12 months?” which included the options of “difficulty falling asleep,” “waking up during sleep,” and “extreme fatigue after waking up.” The response options for all three types of sleep disturbances were “daily,” “once a week,” “several times a month,” “rarely,” and “never.” “Daily,” “once a week,” and “several times a month” responses were regrouped as “yes”; and “rarely” and “never” responses were regrouped as “no.”

Other potential confounding variables

We considered key confounding variables related to sleep disturbance and symptoms of depression and anxiety. As individual characteristics, we chose age and socio-economic status (education level and income). Participants were divided into four age groups: younger than 30, 30 to 39, 40 to 49, and 50 years old or older. Participants were also divided into three groups by educational level: middle school or lower, high school, and college or higher. Average monthly income was divided into intervals of 1,000,000 won (KRW): less than 1,000,000 won; 1,000,000 to 2,000,000 won; 2,000,000 to 3,000,000 won; and greater than or equal to 3,000,000 won.

Working conditions may also contain important factors affecting workers' sleep disturbance and symptoms of depression and anxiety. For work-related characteristics, we explored “weekly working hours,” “overall job satisfaction,” “work schedule,” “type of contract,” and “occupational classification.” We divided work hours into three, as less than 40 hours, 40 to 49 hours, and greater than or equal to 50 hours per week. Job satisfaction was divided into two groups depending on the response to the questionnaire item “Generally, what do you think about your current job?” The answers “Satisfied” and “Very satisfied” were regrouped as “Satisfied”; and the answers “Not satisfied at all” and “Not very satisfied” were regrouped as “Unsatisfied.” Job schedules were also considered, because workers who are assigned irregular schedules are usually exposed to higher risk of sleep disturbance and symptoms of depression and anxiety. KWCS contains a question about whether the workers perform shift work. We categorized shift work into two groups: “yes” and “no.” KWCS also contains a question inquiring about the types of contracts (permanent or temporary) held by paid workers. A permanent working status is defined as a contract of employment including a stipulation of regular retirement or pension for retirement. A temporary working status is defined as including daily or temporarily employed workers. Occupational classifications were categorized into “white-collar” including managers, professionals, and technicians; “service and sales”; and “blue-collar” including agriculture and fishery workers, skilled workers, and machine operators.

Statistical analysis

We performed χ2 tests to compare the differences in individual and work-related characteristics of those with and without anxiety, depression, or sleep disturbance, separately for men and women. The odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for having anxiety, depression, or sleep disturbance were calculated using a fully adjusted multiple logistic regression model and stratified by gender. A P value of < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were completed using SPSS version 23 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Ethics statement

The KWCS questionnaire was collected after receiving written informed consent from all participants. Personally identifiable information was deleted before data analysis. This study is a secondary data analysis, which is approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Gachon Gil Hospital (IRB No. GFIRB2019-267).

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the basic demographic characteristics of the study participants, based on individual anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance status, as well as the working conditions as related to emotional demand. There were 23,128 respondents in our research, with the prevalence of depression comprising 2.3% (n = 523), anxiety comprising 2.7% (n = 626), sleep disturbance in the form of difficulty falling asleep comprising 4.5% (n = 1,050), sleep disturbance in the form of waking up during sleep comprising 4.0% (n = 905), and sleep disturbance in the form of extreme fatigue after waking up comprising 4.2% (n = 971).

Table 1

Basic characteristics of study participants

|

Variables |

No. (%) |

|

Total participants |

23,128 (100) |

|

Gender |

|

|

Men |

11,007 (47.6) |

|

Women |

12,121 (52.4) |

|

Age group, yr |

|

|

< 30 |

2,794 (12.1) |

|

30–39 |

5,029 (21.7) |

|

40–49 |

5,798 (25.1) |

|

≥ 50 |

9,507 (41.1) |

|

Monthly income, KRW |

|

|

< 1,000,000 |

2,680 (11.6) |

|

1,000,000–1,999,999 |

6,788 (29.3) |

|

2,000,000–2,999,999 |

6,601 (28.5) |

|

≥ 3,000,000 |

7,059 (30.5) |

|

Education level |

|

|

< Middle school |

1,375 (5.9) |

|

< High school |

9,684 (41.9) |

|

≥ College |

12,069 (52.2) |

|

Weekly working hours |

|

|

< 40 |

4,311 (18.6) |

|

40–49 |

12,771 (55.2) |

|

≥ 50 |

6,046 (26.1) |

|

Job satisfaction |

|

|

Satisfied |

17,834 (77.1) |

|

Unsatisfied |

5,294 (22.9) |

|

Shift work |

|

|

No |

20,279 (87.7) |

|

Yes |

2,849 (12.3) |

|

Type of contract |

|

|

Permanent |

17,411 (75.3) |

|

Temporary |

5,717 (24.7) |

|

Occupational classification |

|

|

White collar |

8,979 (38.8) |

|

Service and sales |

6,885 (29.8) |

|

Blue collar |

7,264 (31.4) |

|

Suppressing one's emotions at work |

|

|

Rarely |

4,967 (21.5) |

|

Sometimes |

8,848 (38.3) |

|

Always |

9,313 (40.3) |

|

Engaging with angry clients |

|

|

Rarely |

17,675 (76.4) |

|

Sometimes |

4,571 (19.8) |

|

Always |

882 (3.8) |

|

Depression |

|

|

No |

22,605 (97.7) |

|

Yes |

523 (2.3) |

|

Anxiety |

|

|

No |

22,502 (97.3) |

|

Yes |

626 (2.7) |

|

Difficulty falling asleep |

|

|

No |

22,078 (95.5) |

|

Yes |

1,050 (4.5) |

|

Waking up during sleep |

|

|

No |

22,203 (96.0) |

|

Yes |

905 (4.0) |

|

Extreme fatigue after waking up |

|

|

No |

22,157 (95.8) |

|

Yes |

971 (4.2) |

Tables 2 and

3 show the basic demographic characteristics of the study participants, based on individual mental health outcome status and working conditions, by gender.

Table 2

Basic characteristics of men study participants according to mental health problems

|

Variables |

Depression |

P value |

Anxiety |

P value |

Difficulty falling asleep |

P value |

Waking up during sleep |

P value |

Extreme fatigue after waking up |

P value |

|

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

No. (%) |

No. (%) |

No. (%) |

No. (%) |

No. (%) |

No. (%) |

No. (%) |

No. (%) |

No. (%) |

No. (%) |

|

Total participants |

10,795 (98.1) |

212 (1.9) |

|

10,707 (97.3) |

304 (2.8) |

|

10,535 (95.7) |

472 (4.3) |

|

10,610 (96.4) |

397 (3.6) |

|

10,558 (95.9) |

449 (4.1) |

|

|

Age group, yr |

|

|

0.019 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

0.288 |

|

|

0.573 |

|

|

0.065 |

|

< 30 |

1,339 (98.5) |

21 (1.5) |

1,336 (98.2) |

24 (1.8) |

1,310 (96.3) |

50 (3.7) |

1,320 (97.1) |

40 (2.9) |

1,312 (96.5) |

48 (3.5) |

|

30–39 |

2,660 (98.6) |

38 (1.4) |

2,648 (98.1) |

50 (1.9) |

2,591 (96.0) |

107 (4.0) |

2,598 (96.3) |

100 (3.7) |

2,600 (96.4) |

98 (3.6) |

|

40–49 |

2,651 (98.1) |

51 (1.9) |

2,614 (96.7) |

88 (3.3) |

2,587 (95.7) |

115 (4.3) |

2,601 (96.3) |

101 (3.7) |

2,599 (96.2) |

103 (3.8) |

|

≥ 50 |

4,145 (97.6) |

102 (2.4) |

4,109 (96.8) |

138 (3.2) |

4,047 (95.3) |

200 (4.7) |

4,091 (96.3) |

156 (3.7) |

4,047 (95.3) |

200 (4.7) |

|

Monthly income, KRW |

|

|

0.002 |

|

|

0.193 |

|

|

0.426 |

|

|

0.934 |

|

|

0.097 |

|

< 1,000,000 |

632 (97.7) |

15 (2.3) |

630 (97.4) |

17 (2.6) |

626 (96.8) |

21 (3.2) |

623 (96.3) |

24 (3.7) |

629 (97.2) |

18 (2.8) |

|

1,000,000–1,999,999 |

1,726 (97.0) |

54 (3.0) |

1,733 (97.4) |

47 (2.6) |

1,696 (95.3) |

84 (4.7) |

1,719 (96.6) |

61 (3.4) |

1,698 (95.4) |

82 (4.6) |

|

2,000,000–2,999,999 |

3,132 (98.2) |

56 (1.8) |

3,116 (97.7) |

72 (2.3) |

3,047 (95.6) |

141 (4.4) |

3,076 (96.5) |

112 (3.5) |

3,045 (95.5) |

143 (4.5) |

|

≥ 3,000,000 |

5,305 (98.4) |

87 (1.6) |

5,228 (97.0) |

164 (3.0) |

5,166 (95.8) |

226 (4.2) |

5,192 (96.3) |

200 (3.7) |

5,186 (96.2) |

206 (3.8) |

|

Education level |

|

|

0.114 |

|

|

0.502 |

|

|

0.023 |

|

|

0.281 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

< Middle school |

373 (97.4) |

10 (2.6) |

371 (96.9) |

12 (3.1) |

368 (96.1) |

15 (3.9) |

371 (96.9) |

12 (3.1) |

370 (96.6) |

13 (3.4) |

|

< High school |

4,230 (97.8) |

95 (2.2) |

4,199 (97.1) |

126 (2.9) |

4,111 (95.1) |

214 (4.9) |

4,154 (96.0) |

171 (4.0) |

4,099 (94.8) |

226 (5.2) |

|

≥ College |

6,192 (98.3) |

107 (1.7) |

6,137 (97.4) |

162 (2.6) |

6,056 (96.1) |

243 (3.9) |

6,085 (96.6) |

214 (3.4) |

6,089 (96.7) |

210 (3.3) |

|

Weekly working hours |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

< 40 |

1,120 (97.4) |

30 (2.6) |

1,116 (97.0) |

34 (3.0) |

1,078 (93.7) |

72 (6.3) |

1,081 (94.0) |

69 (6.0) |

1,083 (94.2) |

67 (5.8) |

|

40–49 |

6,183 (98.6) |

89 (1.4) |

6,146 (98.0) |

126 (2.0) |

6,034 (96.2) |

238 (3.8) |

6,090 (97.1) |

182 (2.9) |

6,073 (96.8) |

199 (3.2) |

|

≥ 50 |

3,492 (97.4) |

93 (2.6) |

3,445 (96.1) |

140 (3.9) |

3,423 (95.5) |

162 (4.5) |

3,439 (95.9) |

146 (4.1) |

3,402 (94.9) |

183 (5.1) |

|

Job satisfaction |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

Unsatisfied |

2,625 (95.5) |

123 (4.5) |

2,593 (94.4) |

155 (5.6) |

2,570 (93.5) |

178 (6.5) |

2,594 (94.4) |

154 (5.6) |

2,545 (92.6) |

203 (7.4) |

|

Satisfied |

8,170 (98.9) |

89 (1.1) |

8,114 (98.2) |

145 (1.8) |

7,965 (96.4) |

294 (3.6) |

8,016 (97.1) |

243 (2.9) |

8,013 (97.0) |

246 (3.0) |

|

Shift work |

|

|

0.159 |

|

|

0.576 |

|

|

0.075 |

|

|

0.137 |

|

|

0.235 |

|

No |

9,232 (98.2) |

174 (1.8) |

9,153 (97.3) |

253 (2.7) |

9,016 (95.9) |

390 (4.1) |

9,077 (96.5) |

329 (3.5) |

9,031 (96.0) |

375 (4.0) |

|

Yes |

1,563 (97.6) |

38 (2.4) |

1,554 (97.1) |

47 (2.9) |

1,519 (94.9) |

82 (5.1) |

1,533 (95.8) |

68 (4.2) |

1,527 (95.4) |

74 (4.6) |

|

Type of contract |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

0.024 |

|

|

0.121 |

|

|

0.647 |

|

|

0.303 |

|

Permanent |

8,742 (98.4) |

143 (1.6) |

8,658 (97.4) |

227 (2.6) |

8,491 (95.6) |

394 (4.4) |

8,561 (96.4) |

324 (3.6) |

8,531 (96.0) |

354 (4.0) |

|

Temporary |

2,053 (96.7) |

69 (3.3) |

2,049 (96.6) |

73 (3.4) |

2,044 (96.3) |

78 (3.7) |

2,049 (96.6) |

73 (3.4) |

2,027 (95.5) |

95 (4.5) |

|

Occupational classification |

|

|

0.024 |

|

|

0.110 |

|

|

0.382 |

|

|

0.251 |

|

|

0.001 |

|

White collar |

4,362 (98.4) |

71 (1.6) |

4,329 (97.7) |

104 (2.3) |

4,257 (96.0) |

176 (4.0) |

4,286 (96.7) |

147 (3.3) |

4,283 (96.6) |

150 (3.4) |

|

Service and sales |

2,039 (98.3) |

35 (1.7) |

2,016 (97.2) |

58 (2.8) |

1,983 (95.6) |

91 (4.4) |

2,002 (96.5) |

72 (3.5) |

1,996 (96.2) |

78 (3.8) |

|

Blue collar |

4,394 (97.6) |

106 (2.4) |

4,362 (96.9) |

138 (3.1) |

4,295 (95.4) |

205 (4.6) |

4,322 (96.0) |

178 (4.0) |

4,279 (95.1) |

221 (4.9) |

|

Suppressing one's emotions at work |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

Rarely |

2,449 (98.8) |

30 (1.2) |

2,438 (98.3) |

41 (1.7) |

2,423 (97.7) |

56 (2.3) |

2,430 (98.0) |

49 (2.0) |

2,418 (97.5) |

61 (2.5) |

|

Sometimes |

4,292 (98.5) |

66 (1.5) |

4,272 (98.0) |

86 (2.0) |

4,177 (95.8) |

181 (4.2) |

4,222 (96.9) |

136 (3.1) |

4,210 (96.6) |

148 (3.4) |

|

Always |

4,054 (97.2) |

116 (2.8) |

3,997 (95.9) |

173 (4.1) |

3,935 (94.4) |

235 (5.6) |

3,958 (94.9) |

212 (5.1) |

3,930 (94.2) |

240 (5.8) |

|

Engaging with angry clients |

|

|

0.004 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

Rarely |

8,584 (98.3) |

149 (1.7) |

8,522 (97.6) |

211 (2.4) |

8,445 (96.7) |

288 (3.3) |

8,487 (97.2) |

246 (2.8) |

8,458 (96.9) |

275 (3.1) |

|

Sometimes |

1,914 (97.2) |

56 (2.8) |

1,895 (96.2) |

75 (3.8) |

1,829 (92.8) |

141 (7.2) |

1,852 (94.0) |

118 (6.0) |

1,832 (93.0) |

138 (7.0) |

|

Always |

297 (97.7) |

7 (2.3) |

290 (95.4) |

14 (4.6) |

261 (85.9) |

43 (14.1) |

271 (89.1) |

33 (10.9) |

268 (88.2) |

36 (11.8) |

Table 3

Basic characteristics of women study participants according to mental health problems

|

Variables |

Depression |

P value |

Anxiety |

P value |

Difficulty falling asleep |

P value |

Waking up during sleep |

P value |

Extreme fatigue after waking up |

P value |

|

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

No. (%) |

No. (%) |

No. (%) |

No. (%) |

No. (%) |

No. (%) |

No. (%) |

No. (%) |

No. (%) |

No. (%) |

|

Total participants |

11,810 (97.4) |

311 (2.6) |

|

11,795 (97.3) |

326 (2.7) |

|

11,543 (95.2) |

578 (4.8) |

|

11,593 (95.6) |

528 (4.4) |

|

11,599 (95.7) |

522 (4.3) |

|

|

Age group, yr |

|

|

0.002 |

|

|

0.071 |

|

|

0.271 |

|

|

0.468 |

|

|

0.946 |

|

< 30 |

1,406 (98.0) |

28 (2.0) |

1,394 (97.2) |

40 (2.8) |

1,361 (94.9) |

73 (5.1) |

1,364 (95.1) |

70 (4.9) |

1,369 (95.5) |

65 (4.5) |

|

30–39 |

2,292 (98.3) |

39 (1.7) |

2,282 (97.9) |

49 (2.1) |

2,232 (95.8) |

99 (4.2) |

2,235 (95.9) |

96 (4.1) |

2,232 (95.8) |

99 (4.2) |

|

40–49 |

3,014 (97.4) |

82 (2.6) |

3,021 (97.6) |

75 (2.4) |

2,959 (95.6) |

137 (4.4) |

2,972 (96.0) |

124 (4.0) |

2,967 (95.8) |

129 (4.2) |

|

≥ 50 |

5,098 (96.9) |

162 (3.1) |

5,098 (96.9) |

162 (3.1) |

4,991 (94.9) |

269 (5.1) |

5,022 (95.5) |

238 (4.5) |

5,031 (95.6) |

229 (4.4) |

|

Monthly income, KRW |

|

|

0.051 |

|

|

0.117 |

|

|

0.038 |

|

|

0.123 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

< 1,000,000 |

1,970 (96.9) |

63 (3.1) |

1,965 (96.7) |

68 (3.3) |

1,957 (96.3) |

76 (3.7) |

1,950 (95.9) |

83 (4.1) |

1,978 (97.3) |

55 (2.7) |

|

1,000,000–1,999,999 |

4,869 (97.2) |

139 (2.8) |

4,874 (97.3) |

134 (2.7) |

4,758 (95.0) |

250 (5.0) |

4,775 (95.3) |

233 (4.7) |

4,779 (95.4) |

229 (4.6) |

|

2,000,000–2,999,999 |

3,345 (98.0) |

68 (2.0) |

3,336 (97.7) |

77 (2.3) |

3,232 (94.7) |

181 (5.3) |

3,257 (95.4) |

156 (4.6) |

3,233 (94.7) |

180 (5.3) |

|

≥ 3,000,000 |

1,626 (97.5) |

41 (2.5) |

1,620 (97.2) |

47 (2.8) |

1,596 (95.7) |

71 (4.3) |

1,611 (96.6) |

56 (3.4) |

1,609 (96.5) |

58 (3.5) |

|

Education level |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

0.154 |

|

|

0.026 |

|

|

0.030 |

|

|

0.002 |

|

< Middle school |

963 (97.1) |

29 (2.9) |

963 (97.1) |

29 (2.9) |

943 (95.1) |

49 (4.9) |

936 (94.4) |

56 (5.6) |

962 (97.0) |

30 (3.0) |

|

< High school |

5,191 (96.9) |

168 (3.1) |

5,200 (97.0) |

159 (3.0) |

5,074 (94.7) |

285 (5.3) |

5,114 (95.4) |

245 (4.6) |

5,092 (95.0) |

267 (5.0) |

|

≥ College |

5,656 (98.0) |

114 (2.0) |

5,632 (97.6) |

138 (2.4) |

5,526 (95.8) |

244 (4.2) |

5,543 (96.1) |

227 (3.9) |

5,545 (96.1) |

225 (3.9) |

|

Weekly working hours |

|

|

0.190 |

|

|

0.082 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

< 40 |

3,070 (97.1) |

91 (2.9) |

3,060 (96.8) |

101 (3.2) |

2,968 (93.9) |

193 (6.1) |

2,970 (94.0) |

191 (6.0) |

2,992 (94.7) |

169 (5.3) |

|

40–49 |

6,348 (97.7) |

151 (2.3) |

6,342 (97.6) |

157 (2.4) |

6,224 (95.8) |

275 (4.2) |

6,259 (96.3) |

240 (3.7) |

6,266 (96.4) |

233 (3.6) |

|

≥ 50 |

2,392 (97.2) |

69 (2.8) |

2,393 (97.2) |

68 (2.8) |

2,351 (95.5) |

110 (4.5) |

2,364 (96.1) |

97 (3.9) |

2,341 (95.1) |

120 (4.9) |

|

Job satisfaction |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

Unsatisfied |

2,406 (94.5) |

140 (5.5) |

2,415 (94.9) |

131 (5.1) |

2,342 (92.0) |

204 (8.0) |

2,349 (92.3) |

197 (7.7) |

2,339 (91.9) |

207 (8.1) |

|

Satisfied |

9,404 (98.2) |

171 (1.8) |

9,380 (98.0) |

195 (2.0) |

9,201 (96.1) |

374 (3.9) |

9,244 (96.5) |

331 (3.5) |

9,260 (96.7) |

315 (3.3) |

|

Shift work |

|

|

0.258 |

|

|

0.119 |

|

|

0.141 |

|

|

0.926 |

|

|

0.071 |

|

No |

10,600 (97.5) |

273 (2.5) |

10,589 (97.4) |

284 (2.6) |

10,365 (95.3) |

508 (4.7) |

10,400 (95.6) |

473 (4.4) |

10,417 (95.8) |

456 (4.2) |

|

Yes |

1,210 (97.0) |

38 (3.0) |

1,206 (96.6) |

42 (3.4) |

1,178 (94.4) |

70 (5.6) |

1,193 (95.6) |

55 (4.4) |

1,182 (94.7) |

66 (5.3) |

|

Type of contract |

|

|

0.047 |

|

|

0.252 |

|

|

0.241 |

|

|

0.471 |

|

|

0.612 |

|

Permanent |

8,323 (97.6) |

203 (2.4) |

8,306 (97.4) |

220 (2.6) |

8,132 (95.4) |

394 (4.6) |

8,162 (95.7) |

364 (4.3) |

8,164 (95.8) |

362 (4.2) |

|

Temporary |

3,487 (97.0) |

108 (3.0) |

3,489 (97.1) |

106 (2.9) |

3,411 (94.9) |

184 (5.1) |

3,431 (95.4) |

164 (4.6) |

3,435 (95.5) |

160 (4.5) |

|

Occupational classification |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

0.096 |

|

|

0.003 |

|

|

0.022 |

|

|

0.001 |

|

White collar |

4,463 (98.2) |

83 (1.8) |

4,442 (97.7) |

104 (2.3) |

4,362 (96.0) |

184 (4.0) |

4,377 (96.3) |

169 (3.7) |

4,380 (96.3) |

166 (3.7) |

|

Service and sales |

4,673 (97.1) |

138 (2.9) |

4,667 (97.0) |

144 (3.0) |

4,545 (94.5) |

266 (5.5) |

4,589 (95.4) |

222 (4.6) |

4,563 (94.8) |

248 (5.2) |

|

Blue collar |

2,674 (96.7) |

90 (3.3) |

2,686 (97.2) |

78 (2.8) |

2,636 (95.4) |

128 (4.6) |

2,627 (95.0) |

137 (5.0) |

2,656 (96.1) |

108 (3.9) |

|

Suppressing one's emotions in the workplace |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

Rarely |

2,452 (98.6) |

36 (1.4) |

2,450 (98.5) |

38 (1.5) |

2,418 (97.2) |

70 (2.8) |

2,399 (96.4) |

89 (3.6) |

2,424 (97.4) |

64 (2.6) |

|

Sometimes |

4,378 (97.5) |

112 (2.5) |

4,384 (97.6) |

106 (2.4) |

4,310 (96.0) |

180 (4.0) |

4,328 (96.4) |

162 (3.6) |

4,339 (96.6) |

151 (3.4) |

|

Always |

4,980 (96.8) |

163 (3.2) |

4,961 (96.5) |

182 (3.5) |

4,815 (93.6) |

328 (6.4) |

4,866 (94.6) |

277 (5.4) |

4,836 (94.0) |

307 (6.0) |

|

Engaging with angry clients |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

Rarely |

8,748 (97.8) |

194 (2.2) |

8,741 (97.8) |

201 (2.2) |

8,645 (96.7) |

297 (3.3) |

8,650 (96.7) |

292 (3.3) |

8,666 (96.9) |

276 (3.1) |

|

Sometimes |

2,518 (96.8) |

83 (3.2) |

2,510 (96.5) |

91 (3.5) |

2,391 (91.9) |

210 (8.1) |

2,433 (93.5) |

168 (6.5) |

2,427 (93.3) |

174 (6.7) |

|

Always |

544 (94.1) |

34 (5.9) |

544 (94.1) |

34 (5.9) |

507 (87.7) |

71 (12.3) |

510 (88.2) |

68 (11.8) |

506 (87.5) |

72 (12.5) |

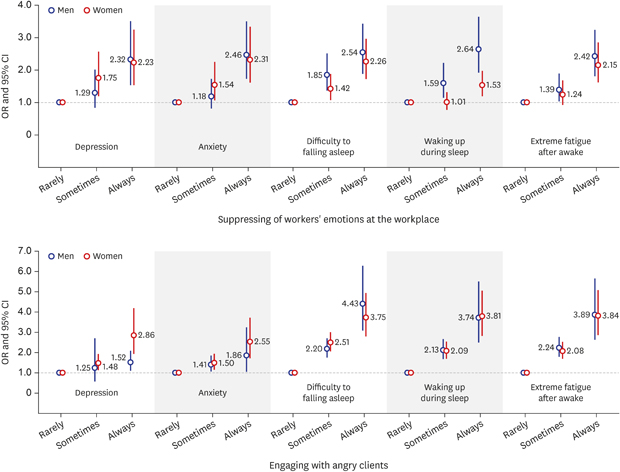

Figs. 2 and

3 show the stratified analysis of the groups of emotional labor, comparing the effects of suppressing one's emotions in the workplace (

Fig. 2) and engaging with angry clients, on depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbance (

Fig. 3). These results showed increasing trends between mental health outcome and emotional labor levels at work.

| Fig. 2

Multiple logistic regression analysis of suppressing one's emotions at work, and depression, anxiety and sleep disturbance stratified by gender.

OR = odds ratio, CI = confidence interval.

|

| Fig. 3

Multiple logistic regression analysis of engaging with angry customers at work, and depression, anxiety and sleep disturbance stratified by gender.

OR = odds ratio, CI = confidence interval.

|

In men workers who suppressed emotions at work, the OR references between the two factors, and the OR values of the “Rarely” group were set as references. The OR values of the “Sometimes” group for depression, anxiety, difficulty falling asleep, waking up during sleep, and extreme fatigue after waking up were higher than those of the “Rarely” group at a statistically significant level (

P values of < 0.05) except for depression and anxiety (

Fig. 2). The OR values of the “Always” group were higher than that of the “Sometimes” group for all mental health outcomes at a statistically significant level. The relevant OR values for depression, anxiety, difficulty falling asleep, waking up during sleep, and extreme fatigue after waking up were 2.32 (95% CI, 1.53–3.51), 2.46 (95% CI, 1.73–3.50), 2.54 (95% CI, 1.88–3.43), 2.64 (95% CI, 1.92–3.64), and 2.42 (95% CI, 1.81–3.24), respectively.

In women workers who suppressed emotions at work, the OR values of the “Sometimes” group were higher than those of the “Rarely” group at a statistically significant level for all mental health outcomes except for sleep disturbance in the form of waking up during sleep (

Fig. 2). Furthermore, the OR values of the “Always” group were also higher than those of the “Sometimes” group at a statistically significant level. The OR values for depression, anxiety, difficulty falling asleep, waking up during sleep, and extreme fatigue after waking up were 2.23 (95% CI, 1.53–3.25), 2.31 (95% CI, 1.61–3.33), 2.26 (95% CI, 1.72–2.96), 1.53 (95% CI, 1.19–1.97), and 2.15 (95% CI, 1.62–2.85), respectively.

Data on men workers engaging with angry clients yielded similar results (

Fig. 3). The OR values of the “Sometimes” group were higher than those of the “Rarely” group at a statistically significant level for all mental health outcomes except for depression. Furthermore, the OR values of the “Always” group were also higher than those of the “Sometimes” group at a statistically significant level. The OR values for depression, anxiety, difficulty falling asleep, waking up during sleep, and extreme fatigue after waking up were 1.52 (95% CI, 1.10–2.10), 1.86 (95% CI, 1.05–3.27), 4.43 (95% CI, 3.11–6.33), 3.74 (95% CI, 2.51–5.55), and 3.89 (95% CI, 2.65–5.70), respectively.

Data on women workers engaging with angry clients returned similar results (

Fig. 3). The OR values of the “Sometimes” group were higher than those of the “Rarely” group at a statistically significant level for all mental health outcomes. All OR values of the “Always” group were higher than those of the “Sometimes” group at a statistically significant level for all mental health outcomes. The OR values for depression, anxiety, difficulty falling asleep, waking up during sleep, and extreme fatigue after waking up were 2.86 (95% CI, 1.94–4.22), 2.55 (95% CI, 1.73–3.75), 3.75 (95% CI, 2.82–4.98), 3.81 (95% CI, 2.84–5.09), and 3.84 (95% CI, 2.88–5.12), respectively.

Additionally, we analyzed the interaction between the two factors of “suppressing one's emotion at work” and “engaging with angry clients.” There were no statistically significant results (Results are not presented). Only a dose-response relationship was found between the two factors.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to investigate the effect of customer-facing jobs on mental health problems, with a focus on sleep disturbance, anxiety, and depression symptoms among Korean workers. This research expands our knowledge of the effects of excessive emotional demands on human mental health. The findings of this study are particularly useful for revealing the association between sleep disturbance, anxiety, and depression, and the emotional demands incurred by having to engage with complaining customers and suppressing one's emotions during work.

We found a positive association between the symptoms of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbance and increased emotional labor among Korean wage workers. As the frequency of engaging with angry customers increased, the symptoms of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbance increased; there is a positive association between mental health and increased emotional labor. Among workers engaging with angry customers, compared to the “Rarely” group as a reference point, the “Always” groups showed elevated ORs of 1.52 (95% CI, 1.10–2.10), 1.86 (95% CI, 1.05–3.27), 4.43 (95% CI, 3.11–6.33), 3.74 (95% CI, 2.51–5.55), 3.89 (95% CI, 2.65–5.70) for men workers; and ORs of 2.86 (95% CI, 1.94–4.22), 2.55 (95% CI, 1.73–3.75), 3.75 (95% CI, 2.82–4.98), 3.81 (95% CI, 2.84–5.09), 3.84 (95% CI, 2.88–5.12) for women workers, for depression, anxiety, difficulty falling asleep, waking up during sleep, and extreme fatigue after waking up. For suppressing one's emotions at work, using the “Rarely” group as a reference point, the “Always” group showed elevated ORs of 2.32 (95% CI, 1.53–3.51), 2.46 (95% CI, 1.73–3.50), 2.54 (95% CI, 1.88–3.43), 2.64 (95% CI, 1.92–3.64), 2.42 (95% CI, 1.81–3.24) for men workers; and ORs of 2.23 (95% CI, 1.53–3.25), 2.31 (95% CI, 1.61–3.33), 2.26 (95% CI, 1.72–2.96), 1.53 (95% CI, 1.19–1.97), 2.15 (95% CI, 1.62–2.85) for women workers for depression, anxiety, difficulty falling asleep, waking up during sleep, and extreme fatigue after waking up, respectively. The study findings reveal that excessive emotional demands could constitute a risk factor for a person who is developing symptoms of anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance.

Our findings are consistent with those from other cross-sectional

5678 and case-control studies

9 that documented a positive association between greater emotional demand and the development of anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance.

There may be various possible explanations for our results. The association between the development of anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance, and the stress induced by emotional labor, could be explained from a physiological perspective. There is a known correlation between the development of anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance and the physiological activities of the stress system of the human brain. The stress system comprises two primary systems: the neuroendocrine (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal [HPA]) system and the sympathetic nervous system.

101112 In the neuroendocrine system, over-activation of the HPA axis is the primary mechanism that explains the occurrence of anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance. Stress, as a risk factor, induces cytokine-mediated inflammation and decreased neurogenesis. The impact of acute and chronic stress, through the increase in the amount of pro-inflammatory cytokines, can stimulate the HPA axis to release glucocorticoids.

13 The hypersecretion of this hormone desensitizes the central glucocorticoid receptors to the negative feedback inhibition of the HPA axis. This, indirectly, results in an increased activation of the HPA axis.

10 Approaches aimed at understanding HPA axis hyperactivity in the development of depression involve measuring the levels of cortisol in a person's saliva, plasma, and urine, as well as the potentially increased size (and activity) of their pituitary and adrenal glands—an increased size in these organs form as a response to experienced arousal.

14

The study results could also be explained from a psychological perspective. Emotional labor can have various negative health consequences.

15 In particular, a person's health can be negatively affected if their emotional expressions during work are not an authentic representation of their true beliefs and/or feelings.

7 The “authenticity” of how people express their emotions at work appears to play an important role in its impact on their overall health. One study, involving service sector workers, pointed out that the psychological effects of emotional labor may be linked with the authenticity of one's perception of self.

1 In this study, workers who do not authentically express their own emotions or behaviors were more vulnerable to the psychological consequences of emotional labor, which demonstrates that requiring workers to consciously hide their emotions (or to display emotions that they do not feel) decreases their overall well-being. Suppressing emotions at work may interrupt one's perceptions of those feelings, making them appear as inauthentic, thus leading to the development of anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance. This is also supported by a study conducted in Canada, which uncovered that jobs requiring people to hide their emotions, such as anger and fear, to greater degrees were significantly related with emotional exhaustion and burnout.

16

Moreover, job stressors have a direct relationship to sleep disorders

17; especially emotional demand, including engaging with complaining customers and suppressing emotions at work, is significantly associated with sleep disturbance.

6 Among those with comorbid disorders, while insomnia occurred first in 69% of the comorbid insomnia and depression cases,

18 the risk of developing new major depression was much higher in those who suffered from insomnia at both interviews, compared with those without insomnia (OR, 39.8; 95% CI, 19.8–80.0).

19 Insomnia is one of the risk factors for the development of depression and anxiety disorders; sleep complaints may be the most robust prodromal symptoms reflecting partial depressive or anxiety disorders.

20

Furthermore, the stress from excessive emotional demands could result in various behavioral problems, such as increased cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption, as well as a decrease in a person's engagement in physical activities.

21 Consuming alcohol constitutes an additional risk factor for anxiety and depression.

22 Furthermore, physical inactivity, an unhealthy diet, and smoking habits are also associated with anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance.

23

Finally, service workers usually deal with agitated customers or ill patients. Given the nature of emotional labor, employees are frequently exposed to various traumatic events, such as violence or abusive language. In addition, some workers have been physically assaulted.

2425 A worker who has been exposed to violence at work is more likely to have suffered anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance at some point in their lives.

2627

Consequently, continuous exposure to the stress of undue emotional demands can excessively activate the brain's stress system, involving the HPA axis, sympathetic nervous system, and health behaviors, which all cause anxiety and depression.

The primary strength of our study is that it is based on a well-established, large population-based survey that is representative of Korean society. It must be noted that this was the first study to use the fifth KWCS to find the association between emotional labor and the development of anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance. Past studies were limited in that they used a definition of sleep disturbance without considering multidimensional factors of sleep problems or combined definition of mental health such as anxiety and/or depression.

56 As a follow-up to these previous studies, this study investigated sleep disturbance with multifactorial approaches (falling asleep as “initial,” waking up as maintaining sleep, and fatigue as sleep quality) and both anxiety and depression.

Furthermore, our study accurately reflects the characteristics of workers in Korean society, and, therefore, possesses high statistical power. Moreover, we studied an ethnically homogenous group of Korean workers, which removes the effect of racial differences on the development of anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance.

Furthermore, previous studies focused primarily on specific occupations, such as service workers,

28 nurses, and call center workers.

29 They also classified emotional labor into a single group such as suppressing emotions at work,

30 workers who have to regularly face customers,

31 or exposure to violence during work.

26 In this study, emotional labor workers were defined and stratified into various groups that experienced excessive emotional demands. They were then categorized into two groups: engaging with angry customers or suppressing emotions at work. Therefore, these results meaningfully contribute to the understanding of the association between mental health and excessive emotional demands.

Despite its strengths, this research has a number of limitations. First, our study involved a cross-sectional design, where the causal relationship of excessive emotional demands on mental health could not be fully explained. Therefore, a further longitudinal study will be necessary to assess the potential cause-and-effect relationship between excessive emotional demands and the development of anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance. Second, anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance symptoms of participants were collected through self-assessment tools and were not diagnosed using clinical criteria or medical devices. Therefore, the correlation between excessive emotional demands at work and anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance symptoms may be either under- or overestimated. Therefore, future studies should supplement these results by utilizing objective indicators such as structured questionnaires or diagnostic criteria. Third, we may not have accounted for other important variables related to anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance, such as low self-esteem, a family history of depression, childhood sexual abuse, or other various traumatic experiences.

32 This may include psychosocial work conditions not evaluated by our study. Personality traits is also another important factor that should be considered in future studies. However, the fifth KWCS does not have information regarding the participants' unique personality traits. Nevertheless, the explanatory variables found were retrieved from published, peer-reviewed literature across different studies on emotional labor and mental health. This study is significant as it provides critical implications applicable to the understanding of emotional labor in countries other than Korea.

This study found that engaging with angry customers and suppressing one's emotions at work were significantly associated with the development of anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance in emotional labor workers. These factors suggest that increased attention ought to be paid to emotional stressors experienced by service workers, to ensure their overall good health. In addition, the various stratified groups among emotional laborers and workers experiencing excessive emotional demands have higher associations with anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance. Therefore, strategies should be developed to prevent and manage the mental health of such employees, and a framework must be established to objectively classify the degree of emotional labor experienced and to protect workers at the organization level.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download