INTRODUCTION

The incidence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is increasing in developed countries concomitant to advances in medical therapies and increases in life expectancy. The relationship between CKD and metabolic bone disease is well recognized, particularly the observation that these patients are at greater risk of osteoporosis and may develop renal osteodystrophy. A combination of uraemia and hypocalcaemia results in bone demineralisation and osteomalacia, making this group of patients susceptible to fractures. For patients with end-stage renal failure (ESRF), the relative risk of a hip fracture has been estimated to be 4.4 times that of the general population

1).

Patients with CKD undergoing hip hemiarthroplasty are at a higher risk for complications

2) (e.g., stem loosening)

345). Stem loosening may result in pain and periprosthetic fractures necessitating revision surgery. Indeed, worsening renal function results in poorer bone quality and increases the risk of fracture and complications

34).

Femoral stems may be cemented or uncemented and there is controversy regarding the ideal fixation approach. Advocates for cementing

456) argue that a cemented prosthesis is more optimal in this group of patients, with instant fixation and inter-digitation of cement into poor bone stock as advantages. There is also an argument against cementless implants as CKD patients have impaired physiology that prevents osteointegration between host bone and a press-fit implant

1).

Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD), has now been used to describe the spectrum of conditions of bone pathologies (e.g., hyperparathyroid bone disease, adynamic bone disease, osteomalacia, mixed uremic osteodystrophy)

7). This pathology leads to poor bone quality and unsatisfactory support, resulting in failure at the bone-cement interface; higher failure rates in a cemented stem for this group of patients is possible.

The null hypothesis tested here is that there is no difference between cemented and uncemented stem loosening rates in patients with CKD who receive a hip hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fractures. The secondary aim of this study is to determine the effect of increasing severity of renal disease on the rate of loosening.

Go to :

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a retrospective study of all patients with CKD who underwent a hip hemiarthroplasty for a traumatic femoral neck fracture over a 10-year period between 2003 and 2013. Ethics board committee (National Health Group) approval was obtained prior to commencement of the study (DSRB reference 2014/00300).

The inclusion criteria were: i) diagnosis of CKD (Stage 1 to ESRF), and ii) minimum two-year follow-up after a bipolar hemiarthroplasty. The choice of implant was surgeon dependant. Patients recruited would have an immediate postoperative X-ray as well as sequential X-rays performed at follow-up for comparison and assessment of potential loosening. Exclusion criteria were pathological fractures or loosening due to infection.

The outcome measure was aseptic loosening of the stem, defined as progressive radiolucency of more than 2 mm, progressive subsidence or migration of the implant

8). Additional specific criteria were used based on whether the stem was cemented or uncemented. For cemented implants, cement mantle fracture and debonding indicated loosening; for uncemented implants, endosteal scalloping and pedestal formation with migration of implants reflected loosening and instability

89). Radiographs were reviewed by two independent orthopaedic surgeons (first and second authors) who were not blinded to the type of fixation method; a third reviewer was used in the event of disputes.

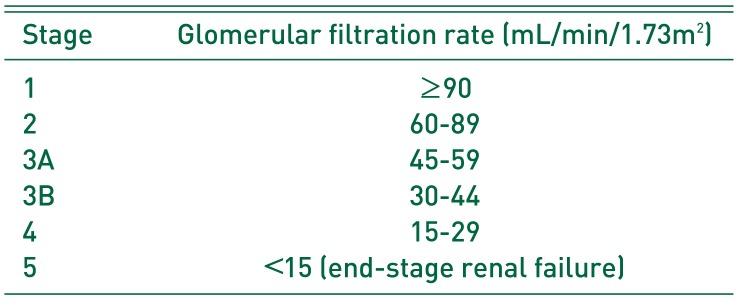

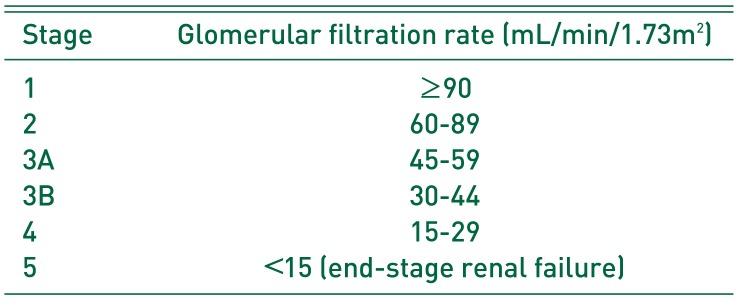

Patients were divided into two groups for analysis according to the type of stem used (group 1, patients with a cemented hip hemiarthroplasty; group 2, patients with an uncemented hip hemiarthroplasty). In each group, patients were further stratified according to renal disease severity. CKD is currently classified according to a patient's glomerular filtration rate, which stratifies them into stages (

Table 1).

Table 1

Classification of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

|

Stage |

Glomerular filtration rate (mL/min/1.73m2) |

|

1 |

≥90 |

|

2 |

60-89 |

|

3A |

45-59 |

|

3B |

30-44 |

|

4 |

15-29 |

|

5 |

<15 (end-stage renal failure) |

Descriptive statistics of the demographic data and outcome variables were calculated. Fisher exact and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used when appropriate. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05. All statistical analysis was conducted using STATA 13 (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA).

Go to :

RESULTS

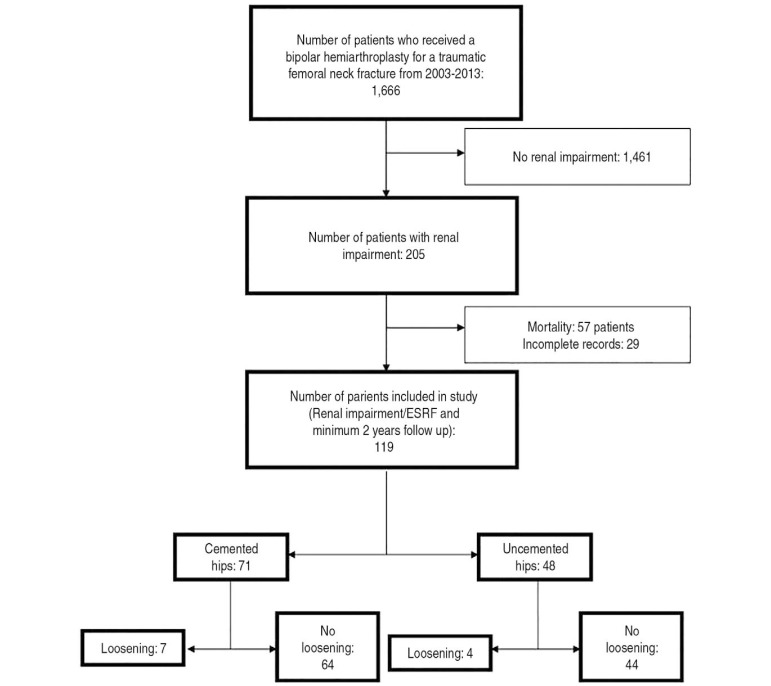

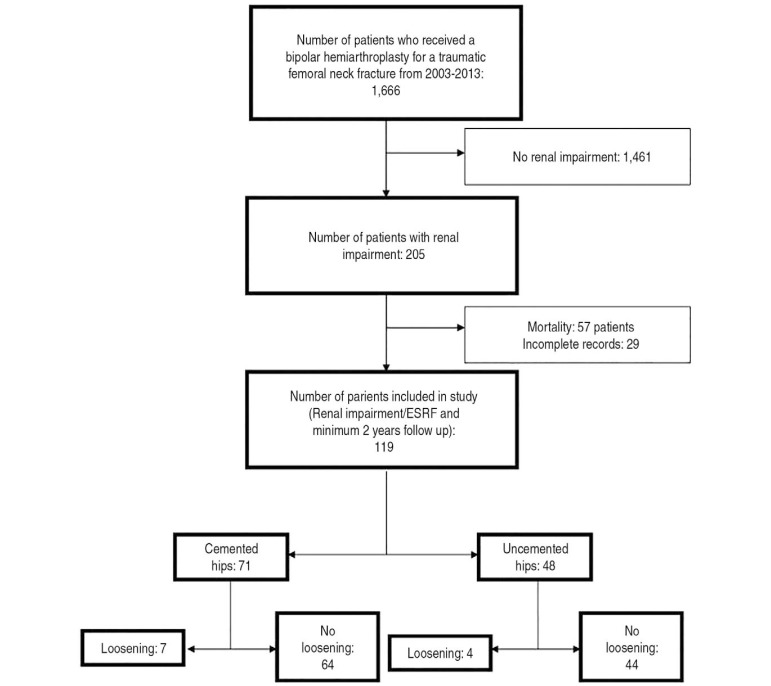

Between 2003 and 2013, Tan Tock Seng Hospital performed 1,666 hip hemiarthroplasties for femoral neck fractures and of these, 205 satisfied inclusion criteria for the current study. Among those included, there were 57 deaths (mortality rate of 27.8%), and 29 patients had incomplete medical records. There were no cases of pathological fractures and two cases of loosening secondary to infection which ultimately contributed to the demise of the patient within the study period and have been accounted for under mortality. The 119 cases included in this study are presented in

Fig. 1.

| Fig. 1

Patients included in our study.

ESRF: end-stage renal failure.

|

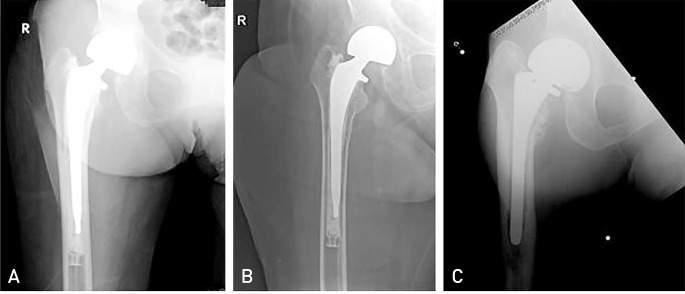

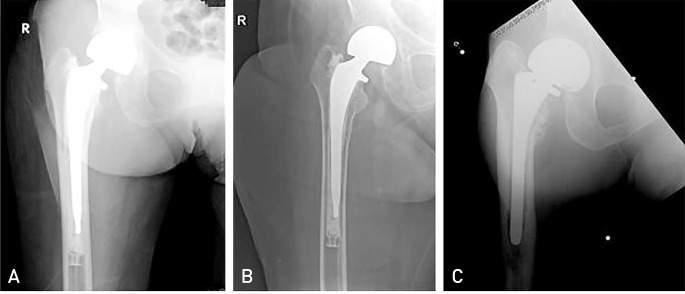

There were 41 male patients and 78 female patients with a mean age of 76.4 years (range, 55–98 years). One-hundred and two hips were treated with a posterior approach and 17 with the direct lateral approach. All patients were allow full weight bearing ambulation the day after surgery. Loosening was observed in 11 cases (9.24%) and no cases required a third radiograph assessment review (

Fig. 2).

| Fig. 2(A) Immediate postoperative X-ray of a cemented hip hemiarthroplasty. (B) Radiolucency of >2 mm around the cement mantle 8 months post-surgery. (C) Uncemented hip hemiarthroplasty with loosening and stem subsidence at 1 year postsurgery.

|

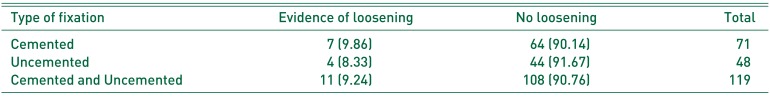

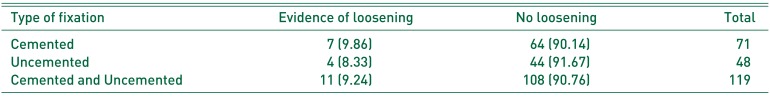

In group 1, there were 71 cases of cemented prosthesis and the cemented stems used were procured from i) Exeter, ii) Johnson & Johnson Corail, and iii) VerSys Heritage. All surgeries involving cemented stems were performed using third-generation cementing techniques. There were 23 male patients and 48 female patients with a mean age of 78.4 years (range, 66–98 years). The average length of follow-up was 28.2 months (range, 24–36 months). There were 7 patients (9.86%) identified with prosthesis loosening. In group 2, there were 48 cases of uncemented prosthesis, all uncemented stems were proximal fit type stems: i) Zimmer M/L taper, ii) Stryker Accolade, iii) Stryker Osteonics, and iv) VerSys Fiber Metal Taper. There were 18 male patients and 30 female patients with a mean age of 73.4 years (range; 55–90 years) and four cases (8.33%) of prosthesis loosening in this group (

Table 2).

Table 2

Rate of Loosening in Cemented and Uncemented Hip Hemiarthroplasties in Our Study

|

Type of fixation |

Evidence of loosening |

No loosening |

Total |

|

Cemented |

7 (9.86) |

64 (90.14) |

71 |

|

Uncemented |

4 (8.33) |

44 (91.67) |

48 |

|

Cemented and Uncemented |

11 (9.24) |

108 (90.76) |

119 |

A comparison between the cemented and uncemented groups revealed no difference in the rate of loosening (

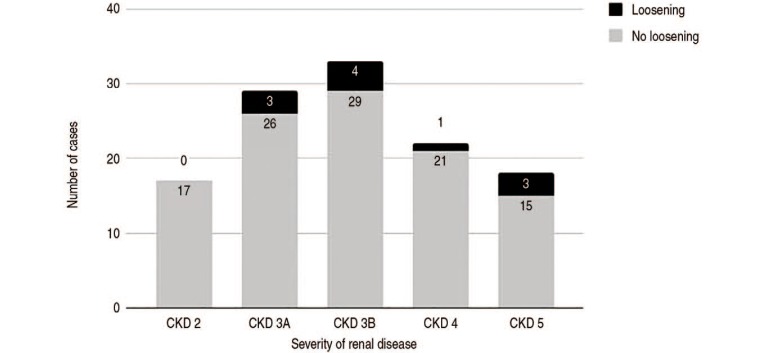

P=0.079). Worsening renal function did not increase the rate of loosening (

P=0.311) (

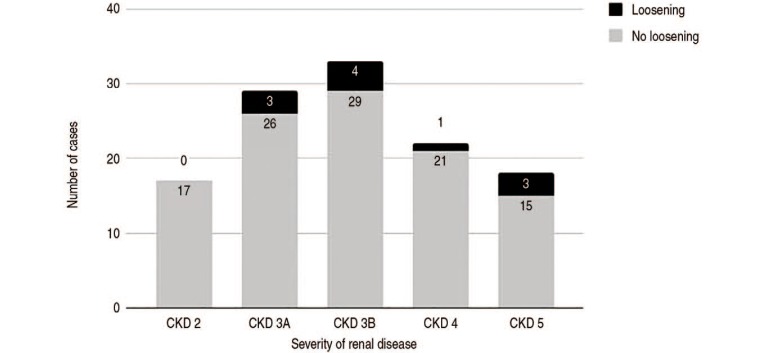

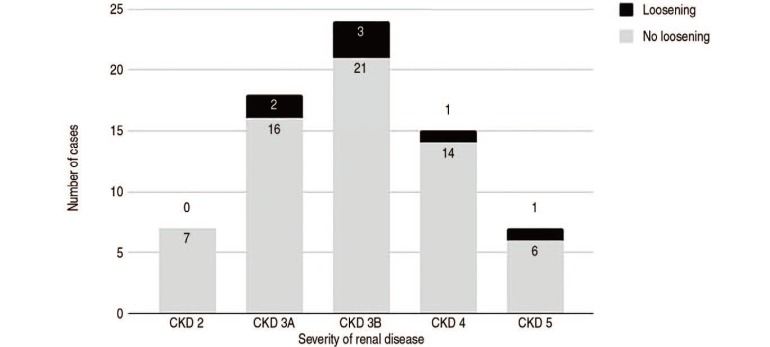

Fig. 3).

| Fig. 3

Effect of worsening renal function in both cemented and uncemented patients. Rate of loosening not increased with worsening renal function. P=0.311.

CKD: chronic kidney disease.

|

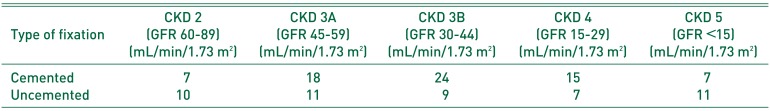

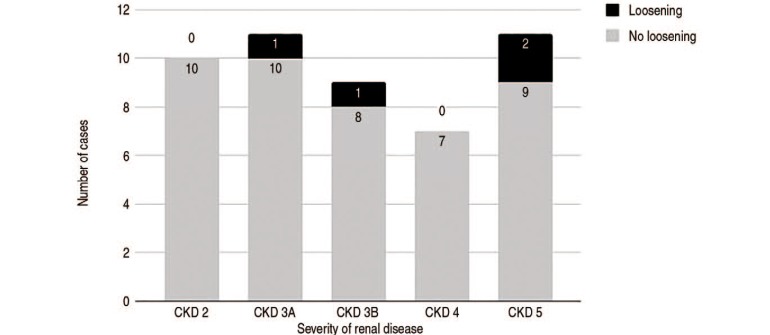

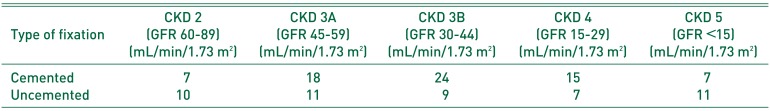

A subgroup analysis of the cases based on the severity of renal disease was performed (

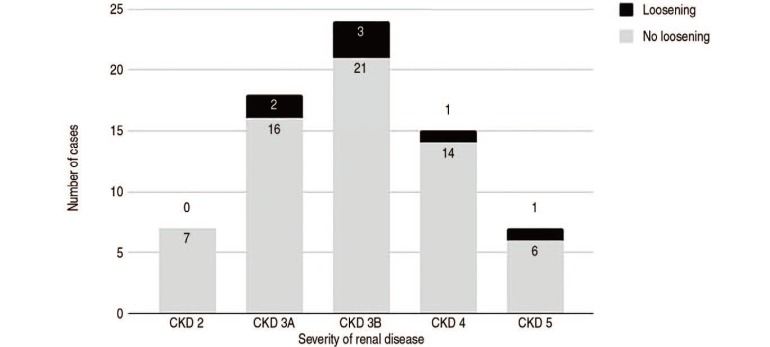

Table 3). In the cemented group, the rate of loosening did not increase with worsening renal function (

P=0.678) (

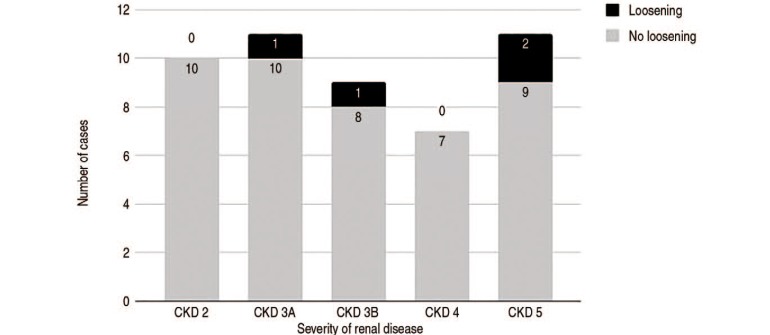

Fig. 4). Similarly, in the uncemented group, the rate of loosening in the uncemented hips was not adversely affected by increasing severity of kidney disease (

P=0.307) (

Fig. 5).

| Fig. 4

Effect of worsening renal function in the cemented group. Rate of loosening not increased with worsening renal function in cemented hips. P=0.678.

CKD: chronic kidney disease.

|

| Fig. 5

Effect of worsening renal function in the uncemented group. Rate of loosening not increased with worsening renal function in cemented hips. P=0.307.

CKD: chronic kidney disease.

|

Table 3

Patients Categorized by Type of Stem Fixation and Severity of Renal Disease

|

Type of fixation |

CKD 2 (GFR 60-89) (mL/min/1.73 m2) |

CKD 3A (GFR 45-59) (mL/min/1.73 m2) |

CKD 3B (GFR 30-44) (mL/min/1.73 m2) |

CKD 4 (GFR 15-29) (mL/min/1.73 m2) |

CKD 5 (GFR <15) (mL/min/1.73 m2) |

|

Cemented |

7 |

18 |

24 |

15 |

7 |

|

Uncemented |

10 |

11 |

9 |

7 |

11 |

Go to :

DISCUSSION

We have shown in this study that the risk of stem loosening is not determined by the type of stem fixation and that the rate of loosening does not increase with increasing severity of renal dysfunction. Substantial improvements in stem survivorships have been reported in groups treated with both cemented and uncemented stems. By the mid-1980s, stem loosening rates of <5% were reported at five to ten years from many different centres. This has largely been attributed to both the evolution of stem designs and cementing techniques. These excellent results continued to be documented beyond ten years

10), however, they have not been reproducible in patients with CKD.

We recognise that prosthetic loosening is a challenging problem in patients with CKD who have poor bone stock and limited physiological reserve, making surgery challenging. Hip arthroplasty in patients with renal diseases have yielded poorer results, with higher rates of loosening and failure. Naito et al.

11) reported a 44% complication rate, more than double that of patients without renal disease; Kalra et al.

5) reported comparable results with a complication rate of 36%. Moreover, morbidity and mortality in patients with renal diseases undergoing hip surgery are also higher; Karaeminogullari et al.

2) reported a mortality of 45% in ESRF patients and Blacha et al.

4) reported 21% mortality rate in his series. These results compare favourably to the results of this study which had a mortality rate of 27.8%, reflecting the high mortality rate in this group of patients. These results suggest that patients in this category are at elevated risk of complications should they require revision surgery for stem loosening. Thus, there is value in determining a superior method of stem fixation. Despite a well-established risk in these patients with renal disease, there is no consensus on the best fixation method. Gualtieri et al.

6) recommended the use of cemented stems in haemodialyzed patients because of poor bone quality and Blacha et al.

4) suggested that cemented stems help reduce postoperative complications. On the other hand, Nagoya et al.

12) suggested that the use of extensively coated, diaphyseal-engaging uncemented stems may prevent stem loosening. In his series of 11 total hip arthroplasties (seven patients) undergoing haemodialysis, there were no cases of loosening at an average follow-up of eight years. Li et al.

13) reported good results with uncemented stems in total hip arthroplasty, with a single case of aseptic loosening requiring revision surgery out of 23 cases. However, these results are reported in patients undergoing elective total hip arthroplasty, which may represent patients who have superior surgical fitness compared to patients who have an acute femoral neck fracture.

Karaeminogullari et al.

2) reported a cumulative survival of 63% at 32 months and Blacha et al.

4) reported stem migration in eight out of 26 cases (30.7%). The relatively lower rate in our series (9.24%) may be attributed to a shorter follow-up period. This does reflect the high complication rates in this particular group of patients and it may be worthwhile to follow them up closely, with timely intervention before a fracture occurs. The studies involved only patients on haemodialysis and involved relatively small sample sizes. We have shown that fixation approach does not influence the rate of loosening in hip hemiarthroplasties in patients with renal diseases. We have also shown that increasing severity of renal disease does not increase the rate of loosening; both cemented and uncemented fixation yield similar results. This is a surprising result as one would assume that the rate of loosening would increase along with the severity of CKD, given that bone quality deteriorates with worsening renal function.

We hypothesize that the driver of loosening and osteolysis in patients with renal disease is not directly related to the severity of the disease but rather the presence of renal osteodystrophy. CKD-MBD is not exclusive to late stages of CKD and may thus explain why rates of loosening was not affected by the severity of renal disease shown in our study as CKD-MBD may already be present

14).

Renal osteodystrophy is a bone pathology exclusively associated with CKD and affects bone quality. The mineral and endocrine functions disrupted in CKD are critically important in the regulation of bone remodelling, and as a result, bone strength diminishes and bones are thus are prone to fractures and abnormalities. Multiple biomarkers have been developed and can be broadly classified into markers of bone turnover, formation and resorption. Given that the bone remodelling process is complex, it is unreasonable to expect that a single biomarker could portray all these changes and thus, there is no one single biomarker that is accepted as a gold standard diagnostic tool

15). Moreover, biomarkers do not reflect bone histomorphometry. Currently, the gold standard for diagnosis is a transiliac bone biopsy and histomorphometry with double labelled tetracycline or its derivatives. This test is not commonly done and as a result, renal osteodystrophy is often underdiagnosed or diagnosed late; none of the patients in our study had this test performed. Parathyroid hormone (PTH) is used as a surrogate for CKD-MBD

1516), a retrospective review revealed that eight of the eleven patients with loosening required PTH and that all eight cases had elevated PTH levels as a result of secondary or tertiary hyperparathyroidism.

We recommend that all patients with renal impairment are followed-up closely with interval X-rays for possible loosening, not just those with ESRF. As shown, at the end of a two-year period, a significant number of patients without ESRF can be affected. We also recommend that biomarkers associated with renal osteodystrophy (e.g., PTH), be evaluated in hip fracture patients with renal impairment, to identify patients with potential renal osteodystrophy so that they may be referred and worked up by nephrologists and receive timely treatment. Hip fractures may well be the first presentation of renal osteodystrophy, and early treatment can potentially retard or prevent osteolysis.

Our study is unique: it has looked into patients with a range of chronic renal disease instead of ESRF alone and has revealed that the severity of disease does not affect the rate of loosening. Most studies on hip fractures in patients with CKD have involved patients with ESRF exclusively

2,

3,

4,

5,

6). However, it needs to be recognised that ESRF is the end point of a spectrum, and thus CKD needs to be studied in its entirety. In addition, with the recognition of CKDMBD, we understand that inferior bone quality and poor structural support can occur at any stage of renal disease. Most of the literature has revolved between the association between ESRF and total hip arthroplasty with limited literature involving hemiarthroplasties, The strength of this study is that it represents one of the largest series to date

2356).

We acknowledge that there are limitations to our study. Being a retrospective study, patients are lost to follow-up and we are only able to determine association, not causation. Loosening is an uncommon complication, and therefore the occurrences of an event are rare, making the study underpowered. A larger, prospective study should be considered to eliminate statistical bias and elevate the level of evidence.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download