This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Background

Glenoid loosening and postoperative instability are common causes of failed reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA). When soft-tissue problems or large glenoid bone defect interferes with reimplantation in revision RTSA, conversion to hemiarthroplasty can be considered. We present a case series of patients who underwent conversion to hemiarthroplasty due to glenoid loosening and early instability after RTSAs, along with clinical results.

Methods

A total of 72 primary RTSAs using the Aequalis prosthesis were performed at our institution from May 2009 to December 2016. Of these, five patients, including one with humeral neck fracture and absent rotator cuff and four with cuff tear arthropathy, underwent conversion to hemiarthroplasty. Another patient who had RTSA at a local clinic underwent hemiarthroplasty at our institution for unresolved postoperative anterior dislocation. The mean age of the six patients was 71.7 years (range, 62 to 76 years), and the mean follow-up period was 24.4 months (range, 18 to 30 months). Clinical assessments were conducted by using the visual analog scale (VAS), American Shoulder and Elbow Surgery (ASES) score, and University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) shoulder score at the last follow-up.

Results

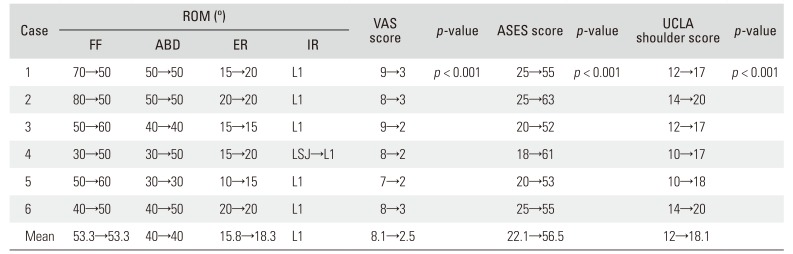

The conversion to hemiarthroplasty in the six patients dramatically improved the mean VAS score (preoperative, 8.1; postoperative, 2.5), ASES score (preoperative, 22.1; postoperative, 56.5), and UCLA score (preoperative, 12; postoperative, 18.1). However, the range of motion was almost unchanged after surgery.

Conclusions

Conversion to hemiarthroplasty can be a good alternative to revision RTSA in patients with serious complications (such as unresolved instability and glenoid loosening) difficult to treat with revision RTSA.

Go to :

Keywords: Glenoid loosening, Cuff tear arthropathy, Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty, Hemiarthroplasty

Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) is a useful treatment option for rotator cuff tear arthropathy with a deficient rotator cuff and deteriorated force couples of the four rotator cuff muscles around the shoulder. RTSA has achieved widespread usage and is now regularly used for a variety of indications, which have been extended to cases such as acute proximal humeral fracture, nonunion or malunion of proximal humeral fracture, primary osteoarthritis with or without rotator cuff tear, and rheumatoid arthritis. Although excellent short-term outcomes with restoration of painless range of motion (ROM) have been described in several large series, an increasing body of literature has been devoted to the complications associated with RTSA.

123) Compared with total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA), RTSA has a higher complication rate. The complication rate after TSA was reported to be 12%–14.7%, with prosthetic loosening being the most common complication,

456) whereas the complication rate of RTSA was reported to be 8%–22%. The most common causes of revision surgery after RTSA, in decreasing order of frequency, are prosthetic instability (38%), infection (22%), humeral problems (21%, including loosening, unscrewing, and fracture), and problems of glenoid loosening (13%).

78) Some surgeons reported that the complications of RTSAs could occur in 19%–68% of patients in the form of neurologic injury, instability, periprosthetic fracture, infection scapular notching, mechanical baseplate failure, and acromial fracture.

91011) Glenoid loosening and postoperative shoulder instability are common early complications of RTSA that are difficult to predict and treat. In particular, revision RTSA is difficult to perform in the following conditions

1213): fibrotic scar tissue and adhesion (which can cause difficult wound dissection), difficulty in the removal of the humeral or glenoid component, severe and large bone defect in the humerus, the glenoid being too small for implantation, and uncontrolled infection.

91011) Thus, the surgeon should consider various treatment options according to the causes of failed RTSAs, such as component reimplantation or change, conversion to hemiarthroplasty, and resection arthroplasty (removal of all implants). In a revision RTSA, severe soft tissue or bone defect may interfere with the reimplantation of the glenoid or humeral component and necessitate a bone graft procedure. In this case, conversion to hemiarthroplasty could be considered.

We present a case series of four of the six patients who had glenoid loosening (three patients) and early instability (three patients) after RTSAs and introduce the method of conversion to hemiarthroplasty. Also, we present clinical results of the six hemiarthroplasties assessed to evaluate the effectiveness of the procedure.

METHODS

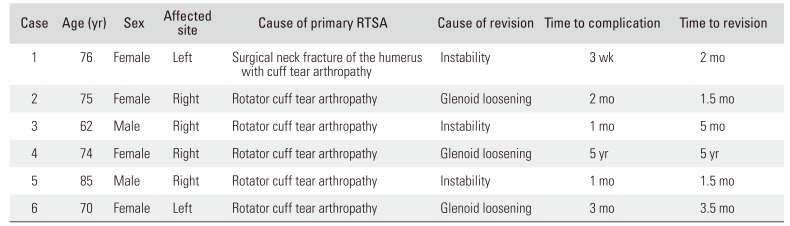

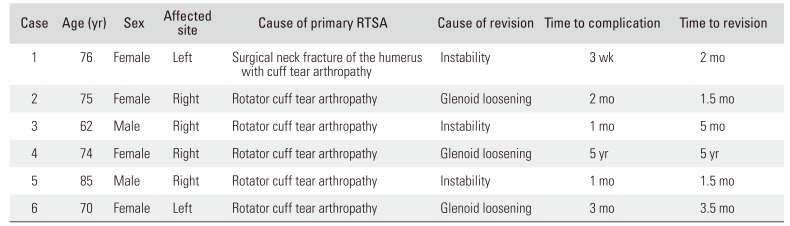

From May 2009 to December 2016, we retrospectively reviewed medical records of all RTSAs performed at our institution and evaluated records of radiological assessment using X-ray, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The protocol of this study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Daejeon Sun Hospital (IRB No. DSH-19-06). Informed consent was waived. A total of 72 consecutive RTSAs were performed at our institution by a single surgeon (ISS). Five of the 72 cases and one case of RTSA that was performed at another institution required revision surgery. The cause of primary RTSA (Aequalis; Tornier, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was three-part fracture of the humeral surgical neck with absent rotator cuff and concomitant advanced osteoarthritis of the glenohumeral joint in one case, and rotator cuff tear arthropathy in the remaining five cases. Among them, there were instability in three cases and glenoid loosening in the other three cases postoperatively. One case had unresolved anterior dislocation after RTSA performed for rotator cuff tear arthropathy and revision. Thus, we performed conversion to hemiarthroplasty (Tornier, Edina, MN, USA) for failed RTSA in all six cases. The mean age of the six patients was 71.7 years (range, 62 to 76 years) and the mean follow-up period was 24.4 months (range, 18 to 30 months). The mean interval between the primary surgery and the revision surgery was 68.0 weeks (range, 9 to 240 weeks) (

Table 1). Radiographs were taken immediately after surgery; at 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery; and at the last follow-up. Subjective pain level was assessed using the visual analog scale (VAS) for pain. Shoulder joint ROM was evaluated using the data on preoperative and postoperative forward flexion, external rotation, internal rotation, and abduction. Clinical assessments were performed using the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) score and the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) score at the last follow-up. Statistical analysis of preoperative and postoperative data was conducted using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test because of the small sample size. A

p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Table 1

Patient Demographics

|

Case |

Age (yr) |

Sex |

Affected site |

Cause of primary RTSA |

Cause of revision |

Time to complication |

Time to revision |

|

1 |

76 |

Female |

Left |

Surgical neck fracture of the humerus with cuff tear arthropathy |

Instability |

3 wk |

2 mo |

|

2 |

75 |

Female |

Right |

Rotator cuff tear arthropathy |

Glenoid loosening |

2 mo |

1.5 mo |

|

3 |

62 |

Male |

Right |

Rotator cuff tear arthropathy |

Instability |

1 mo |

5 mo |

|

4 |

74 |

Female |

Right |

Rotator cuff tear arthropathy |

Glenoid loosening |

5 yr |

5 yr |

|

5 |

85 |

Male |

Right |

Rotator cuff tear arthropathy |

Instability |

1 mo |

1.5 mo |

|

6 |

70 |

Female |

Left |

Rotator cuff tear arthropathy |

Glenoid loosening |

3 mo |

3.5 mo |

Case 1

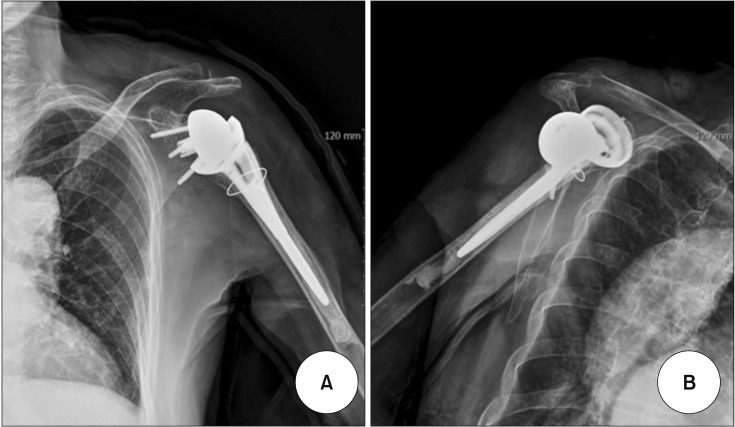

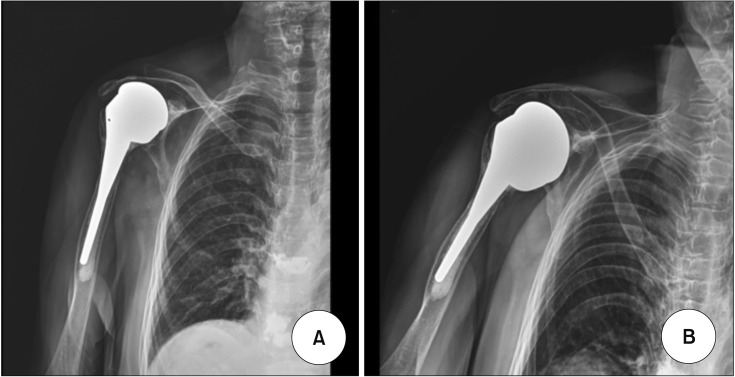

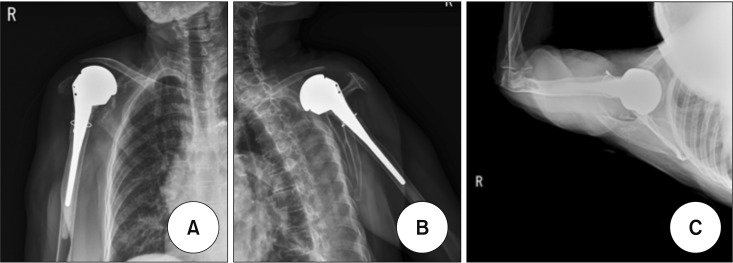

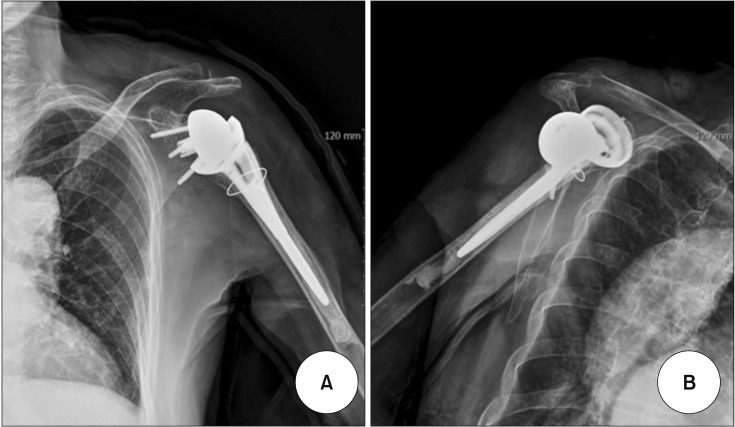

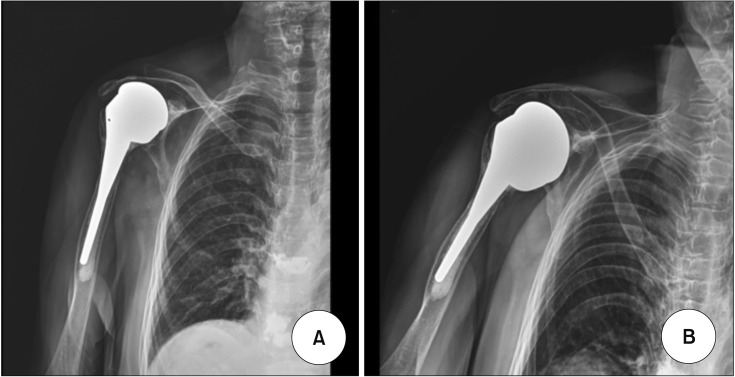

A 76-year-old woman sustained a slip-down injury while performing daily work. She was diagnosed with a three-part fracture of the surgical neck of the right humerus. The glenohumeral joint showed grade 4 osteoarthritis on the glenoid articular surface and humeral head, with a lot of osteophytes. The fractured shoulder joint had an irreparable massive rotator cuff tear involving the subscapularis, supraspinatus, and infraspinatus and showed fat degeneration (Goutallier classification grade 4). We decided to perform RTSA on posttrauma day 5. She was placed in the beach-chair position and operated on under general anesthesia with associated local interscalene block. A deltopectoral approach was used and the fractured greater and lesser tuberosities were retracted to allow for the removal of the head of the humerus for wider exposure of the glenoid. The supraspinatus tendon and the long head of the biceps were divided. The glenoid baseplate was implanted flush to the inferior, anterior, and posterior rims of the glenoid with an inferior inclination of approximately 10° and was secured using 4 lag screws inserted though the glenoid. We inserted the hemisphere and confirmed the stability of the implant. The humeral component was inserted using intramedullary cement in 5° retroversion. We inserted a 6-mm polyethylene bearing after trial reduction. The fractured tuberosities were then sutured to each other and around the neck of the prosthesis in their anatomical position. After the operation, the shoulder was immobilized for 2 days and remained in an ultra-sling for 3 weeks postoperatively before passive ROM was started. Active, active assisted, and isometric exercises were started at 6 weeks, with progression to strengthening exercises at 12 weeks. The shoulder had a dislocation of the glenohumeral joint on postoperative day 7 and she experienced a sharp pain and limited motion. Plain radiographs revealed anterior dislocation of the humerus and polyethylene bearing. We reduced the dislocated shoulder and immobilized the reduced shoulder. We found the redislocation of the shoulder during follow-up at 4 weeks postoperatively but failed to reduce the dislocated joint (

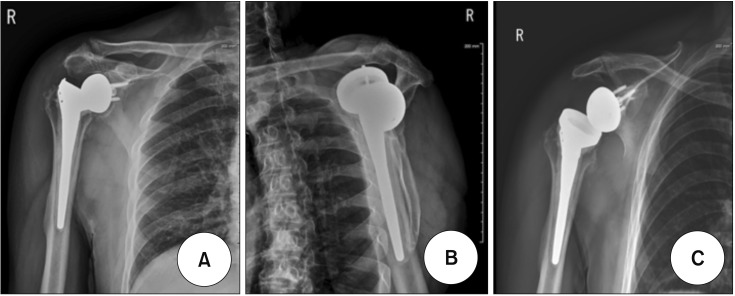

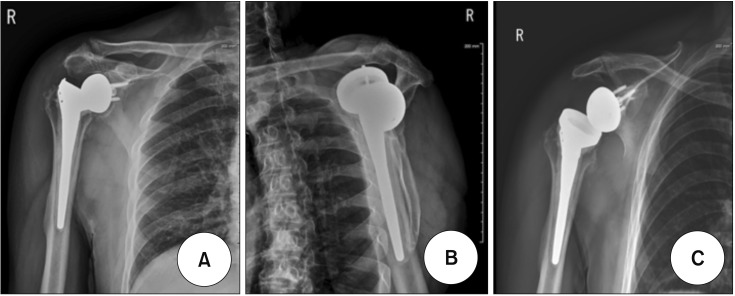

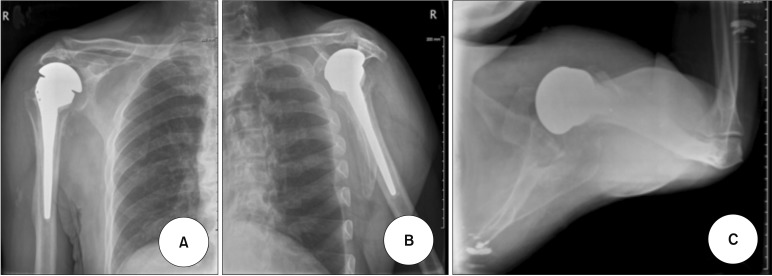

Fig. 1). We diagnosed shoulder instability and postoperative stiffness and decided to perform revision surgery. As in the previous primary surgery, the deltopectoral approach was used to expose the dislocated joint. We removed the glenoid baseplate and hemisphere and inserted a precomposited humeral head for hemiarthroplasty (

Fig. 2). Then, we reattached the detached subscapularis on the lesser tuberosity and closed the fascia in a folded fashion. The VAS score improved from 9 preoperatively to 3 at the last follow-up. Active forward flexion decreased from 70° to 50°, abduction was unchanged at 50°, external rotation minimally increased from 15° to 20°, and internal rotation was unchanged at L1. The ASES score improved from 25 preoperatively to 55 at the last follow-up. The UCLA score improved from 12 preoperatively to 17 at the last follow-up. We did not find any complication such as redislocation, infection, or implant loosening. The greater tuberosity was a little absorbed, but was well maintained at the original position, and the lesser tuberosity was well maintained.

| Fig. 1Anteroposterior view (A) and outlet view (B) of the shoulder of a 76-year-old female patient, showing anterior dislocation of the humeral prosthesis from the glenoid baseplate.

|

| Fig. 2Anteroposterior view (A), outlet view (B), and axial view (C) of the shoulder obtained after conversion to hemiarthroplasty in a 76-year-old female patient. She had a well-positioned prosthesis but minimal upward migration and acetabularization of the acromion.

|

Case 2

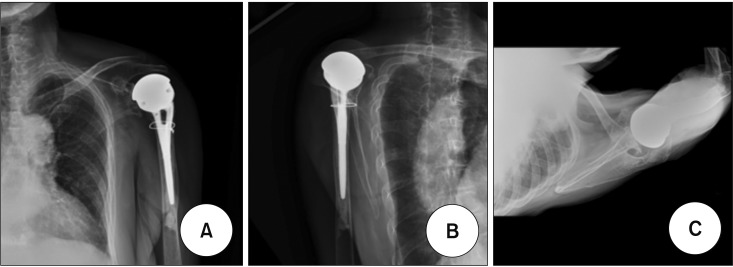

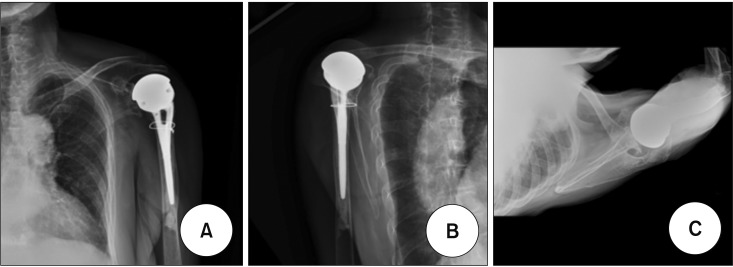

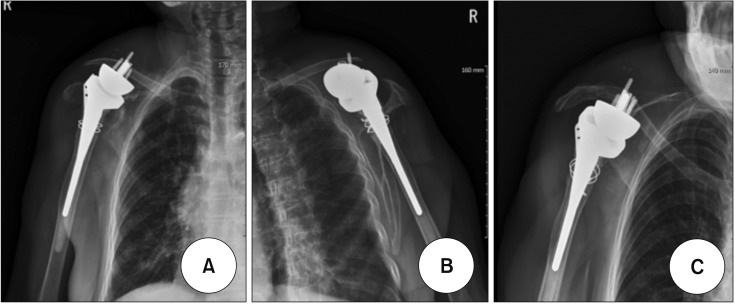

A 75-year-old woman underwent an RTSA of the right shoulder under the impression of rotator cuff tear arthropathy. She experienced sudden pain and swelling on the index shoulder. The 2-month follow-up plain radiographs showed 30° tilting of the glenoid baseplate, upward migration of the two locking screws and two compression screws, suggesting glenoid loosening (

Fig. 3). We decided to perform conversion to hemiarthroplasty, which involved the removal of the loosened baseplate, hemisphere and polyethylene component except the solid-fixed humeral stem, and the insertion of the humeral head component in 5° fixed retroversion (

Fig. 4). We confirmed the stability of the shoulder, reattached the subscapularis tendon, and meticulously closed the joint capsule and fascia. The VAS score improved from 8 preoperatively to 3 at the last follow-up. Active forward flexion decreased from 80° to 50°, abduction was unchanged at 50°, external rotation was unchanged at 20°, and internal rotation was unchanged at L1. The ASES score improved from 25 preoperatively to 63 at the last follow-up. The UCLA score improved from 14 preoperatively to 20 at the last follow-up. She had no complication such as redislocation, infection, or implant loosening.

| Fig. 3Anteroposterior view (A), outlet view (B), and axial view (C) of the shoulder of a 75-year-old female patient, showing upward migration of the two locking screws and two compression screws, suggesting glenoid loosening.

|

| Fig. 4Anteroposterior view (A) and 30° caudal tilt view (B) of the shoulder obtained after conversion to hemiarthroplasty in a 75-year-old female patient with a loosened glenoid baseplate.

|

Case 3

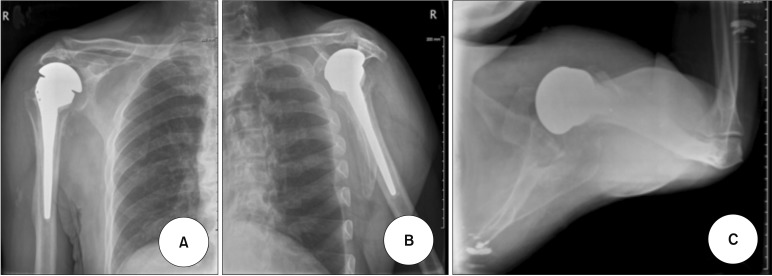

A 62-year-old man with painful limitation of motion on the right shoulder visited our clinic. He underwent an RTSA on the index shoulder under the impression of rotator cuff tear arthropathy and a revision RTSA to change the polyethylene size from 9 to 12 mm at 3 months after the primary surgery at a local clinic. Plain radiographs demonstrated anterior dislocation of the glenohumeral joint, and the shoulder had severe limitation of motion (

Fig. 5). To assess deltoid function, we performed MRI and electromyography (EMG). The MRI revealed a thin deltoid muscle, a dislocated glenohumeral joint that was 2 mm superior to the glenoid baseplate, and neutral rotation of the humerus. The EMG showed right axillary neuropathy and a supraspinatus nerve lesion in the right upper extremity. We decided to perform conversion to hemiarthroplasty because reimplantation was impossible. Using the previous deltopectoral approach, we removed the malpositioned baseplate and hemisphere and inserted the precomposited humeral head for the hemiarthroplasty (

Fig. 6). The VAS score improved from 9 preoperatively to 2 at the last follow-up. Active forward flexion increased from 50° to 60°, abduction was unchanged at 40°, external rotation was unchanged at 15°, and internal rotation was unchanged at L1. The ASES score improved from 20 preoperatively to 52 at the last follow-up. The UCLA score improved from 12 preoperatively to 17 at the last follow-up. There was no complication such as a redislocation, infection, or implant loosening.

| Fig. 5Anteroposterior view (A), outlet view (B), and 30° caudal tilt view (C) of the right shoulder of a 62-year-old male patient with unresolved dislocation and severe stiffness after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. He had axillary neuropathy and a supraspinatus nerve lesion in the right upper extremity.

|

| Fig. 6Anteroposterior view (A), outlet view (B), and axial view (C) of the right shoulder, showing a well-positioned prosthesis after conversion to hemiarthroplasty in a 62-year-old male patient.

|

Case 4

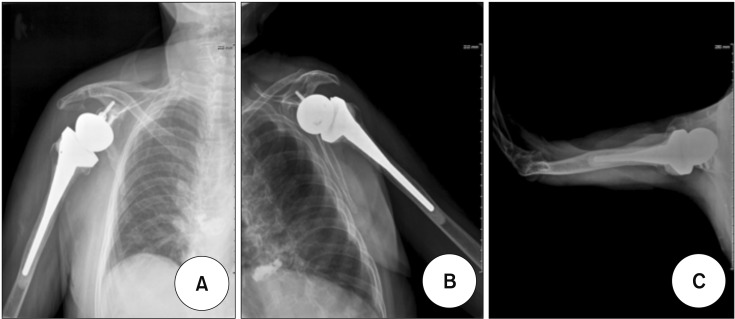

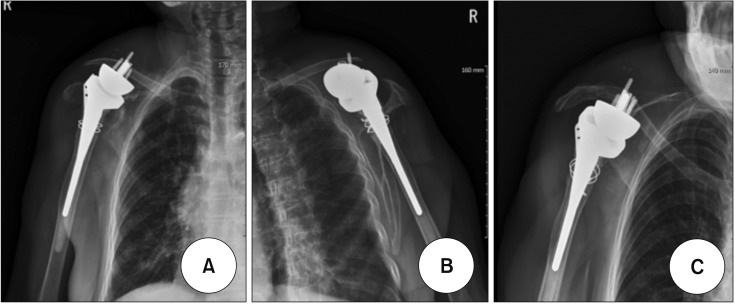

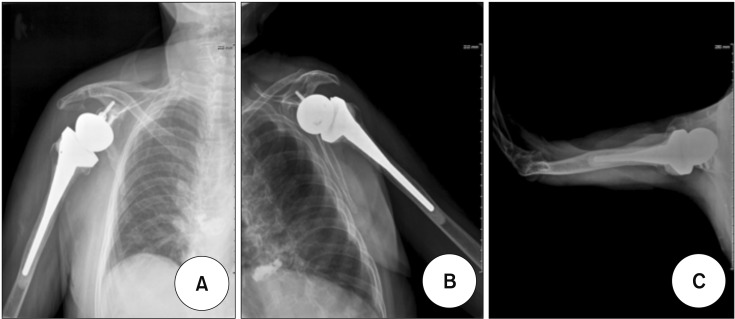

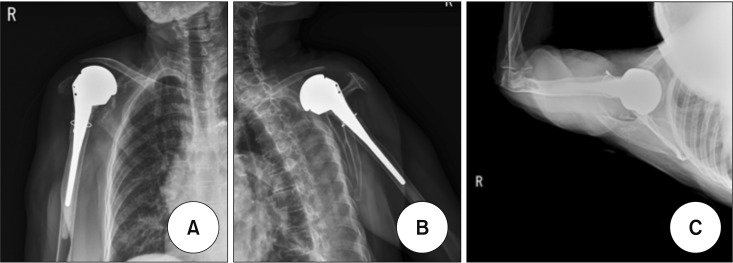

A 74-year-old woman with rheumatoid arthritis underwent RTSA. At 6-month follow-up, the patient had a well-fixed implant, and the glenohumeral joint was functioning well without any complications such as infection, loosening, instability, stiffness, or neurovascular injury. Later, she visited our clinic because of shoulder pain and severe swelling persisting for 3 months. Plain radiographs revealed a displaced upward glenoid baseplate and hemisphere over the clavicle and a well-fixed and well-positioned humeral implant (

Fig. 7). We performed conversion to hemiarthroplasty on this patient (

Fig. 8). The VAS score improved from 8 preoperatively to 2 at the last follow-up. Active forward flexion increased from 30° to 50°, abduction was increased from 30° to 50°, external rotation minimally increased from 15° to 20°, and internal rotation increased from the lumbosacral joint to L1. The ASES score improved from 18 preoperatively to 61 at the last follow-up. The UCLA score improved from 10 preoperatively to 17 at the last follow-up. We did not find any complication such as redislocation, infection, implant, or loosening. The greater tuberosity was a little absorbed but was well maintained at the original position, and the lesser tuberosity was well maintained.

| Fig. 7Anteroposterior view (A), outlet view (B), and 30° caudal tilt view (C) of the shoulder of a 74-year-old female patient with upward displacement of the glenoid baseplate and hemisphere over the clavicle. The humeral component remained well positioned and well fixed.

|

| Fig. 8Anteroposterior view (A), outlet view (B), and axial view (C) of the shoulder, showing the loosened prosthesis. After conversion to hemiarthroplasty, the glenohumeral joint was well reduced.

|

Go to :

RESULTS

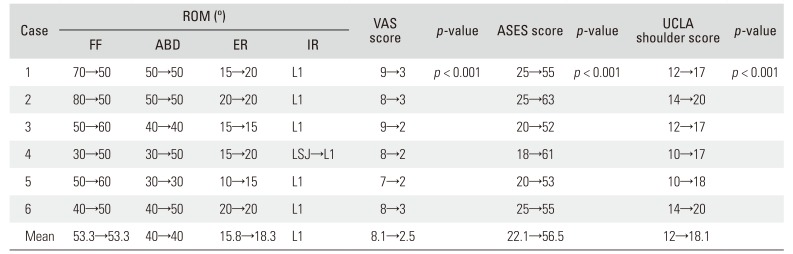

The mean VAS score of the six cases improved from 8.1 to 2.5 postoperatively (

p < 0.001). There was slight increase in the mean external rotation (from 15.8° to 18.3°), but there was no change in forward flexion (53.3°), abduction (40°), and internal rotation (L1) postoperatively. The mean ASES score significantly improved from 22.1 preoperatively to 56.5 postoperatively (

p < 0.001). The mean UCLA score significantly improved from 12.0 preoperatively to 18.1 postoperatively (

p < 0.001). The clinical results of hemiarthroplasty of the six cases showed dramatic improvement in VAS, ASES, and UCLA scores (

Table 2). However, the ROM was almost unchanged between before and after conversion surgery. The last follow-up X-ray showed minimal glenoid erosion by the large metal head, the so-called acetabularization or femoralization of the glenoid.

Table 2

Clinical Results

|

Case |

ROM (°) |

VAS score |

p-value |

ASES score |

p-value |

UCLA shoulder score |

p-value |

|

FF |

ABD |

ER |

IR |

|

1 |

70→50 |

50→50 |

15→20 |

L1 |

9→3 |

p < 0.001 |

25→55 |

p < 0.001 |

12→17 |

p < 0.001 |

|

2 |

80→50 |

50→50 |

20→20 |

L1 |

8→3 |

|

25→63 |

|

14→20 |

|

|

3 |

50→60 |

40→40 |

15→15 |

L1 |

9→2 |

|

20→52 |

|

12→17 |

|

|

4 |

30→50 |

30→50 |

15→20 |

LSJ→L1 |

8→2 |

|

18→61 |

|

10→17 |

|

|

5 |

50→60 |

30→30 |

10→15 |

L1 |

7→2 |

|

20→53 |

|

10→18 |

|

|

6 |

40→50 |

40→50 |

20→20 |

L1 |

8→3 |

|

25→55 |

|

14→20 |

|

|

Mean |

53.3→53.3 |

40→40 |

15.8→18.3 |

L1 |

8.1→2.5 |

|

22.1→56.5 |

|

12→18.1 |

|

Go to :

DISCUSSION

The primary indications for RTSA include cuff tear arthropathy and irreparable massive rotator cuff tear, and RTSA has been considered the last surgical option for restoring shoulder function. Recently, however, because of reports of successful outcomes, its indications have been extended to other conditions such as acute proximal humeral fracture, rheumatoid arthritis, failed shoulder arthroplasty, chronic anterior dislocation, tumors, and severe osteoporosis.

9)

When restoration of rotator cuff function is not feasible, functional recovery of the shoulder can be obtained with a reversed total shoulder prosthesis, which places the glenohumeral center of rotation medially and elongates the remaining deltoid muscle, similarly with a total shoulder prosthesis.

14) Because of the promising functional results of RTSA, it is becoming preferred by a growing number of orthopedic surgeons. However, it has been reported to have a complication rate of 19%–50% and a reoperation rate as high as 33%.

1213151617181920212223) It is generally assumed that most complications will involve the glenoid side, and some humeral complications have already been reported.

Despite advances in surgical modifications that have decreased complications such as inferior glenoid notching, postoperative instability subsequent to RTSA remains as the most frequent complication, and dislocation associated with prosthetic instability is difficult to predict and treat.

1213) Most series, particularly those with a large proportion of revision cases, have reported cases of instability after reverse total shoulder replacement, yet few discussed methods of prevention and treatment.

111213) Gallo et al.

11) suggested that noninfectious instability can result from either inadequate tensioning of the deltoid or impingement of the components by Grammont system, and discussed “global decoaptation,” a condition in which the lack of sufficient tension in the deltoid muscle causes formation of a space between the ball and the socket. There is little to guide the surgeon in determining the correct amount of tension to place on the deltoid.

124) This could be because of preexisting atrophy or insufficiency of the anterior part of the deltoid or because of relative humeral shortening compared with the contralateral side. Preoperative deltoid insufficiency in revision arthroplasty has been probably underestimated; it was reported to be present in 71% according to Gohlke and Rolf.

25) Boileau et al.

1) suggested that proper tensioning of the implant can be roughly gauged by the tension generated within the conjoined tendon after the reduction of the implant.

Wall et al.

26) have reported that the deltopectoral approach seems to negatively influence the incidence of instability. However, complete release of the subscapularis, including the inferior and middle glenohumeral ligaments at the glenoid insertion site, may weaken anterior restraints in deltopectoral approaches. Edwards et al.

27) showed that an irreparable subscapularis at the time of reverse total shoulder replacement is the most significant risk factor for dislocation after implantation using a deltopectoral approach. Boileau et al.

1) suggested that the lack of compromise in the subscapularis tendon in an anterosuperior transdeltoid approach contributes to the lower incidence of instability seen with that approach. Therefore, the subscapularis seems to be of tremendous importance and should be repaired and protected whenever possible.

11317) We encountered three cases of postoperative instability: two of the cases were reducible but could not maintain the reduced position of the prosthesis and the other case had revision RTSA, which eventually resulted in fixed dislocation and severe joint stiffness. It is very difficult to adjust the accurate tension of the deltoid in a failed RTSA because of postoperative instability. Furthermore, one case had postoperative deltoid muscle dysfunction due to axillary neuropathy and supraspinatus nerve lesion of the extremity. In such cases, a revision RTSA cannot maintain the prosthesis in reduced position and lacks the function of the lengthened deltoid lever arm. Furthermore, a sufficient visual operation field to expose the glenoid could not be secured because of severe stiffness around the shoulder. Thus, we chose hemiarthroplasty as an alternative method to revision RTSA to secure the operation field and maintain the reduced position of the prosthesis.

Revision RTSA is often limited by poor bone stock and inadequate soft tissue envelopes from the underlying disease and/or previous procedures. Furthermore, many patients undergoing reverse shoulder replacements are old, medically fragile, and unable to tolerate major surgical revisions. Despite the superior clinical outcomes of revision RTSA, patient factors (patients' volition and medical comorbidity) and surgical factors (adequate device and poor quality of bone and soft tissue) should be considered. We had three cases of glenoid loosening with unscrewing of the baseplate. All three cases showed poor bone stock on the glenoid that was difficult to resolve by bone graft (humeral head or iliac autograft). Unreasonable bone graft and glenoid revision can lead to recurrent loosening of the baseplate even with the so-called bio-RTSA, an alternative method using a glenoid bone graft for the poor glenoid bone stock. Revision RTSA using glenoid bone graft needs a long time to restore shoulder function. Thus, we suggest conversion hemiarthroplasty as an alternative to revision RTSA, because it appears to be a very simple and promising way to relieve pain. However, we cannot expect the functional regain after conversion to hemiarthroplasty because the surgery has a limitation in terms of deltoid and rotator cuff function. All our cases showed improved clinical scores at the last follow-up but did not show improved ROM.

We reported three cases of prosthetic instability and three cases of metallic failure associated with glenoid loosening. These complications could have been caused by errors related to the surgical technique or by the design of the prosthesis. Revision RTSA is a surgical intervention in which prosthetic components are completely or partially changed or removed. However, our cases had no indications for revision RTSA involving prosthetic component change. We believe that removal of a complicated prosthesis should be the last option for pain relief and that maintaining shoulder function is important even if functional recovery cannot be obtained with revision procedure. In this sense, conversion to hemiarthroplasty can be a good alternative for conditions that cannot be treated by revision RTSA.

Hemiarthroplasty, which is a simple and non-technically demanding method, can be a good alternative to revision RTSA to treat serious complications after RTSA, such as unresolved instability or glenoid loosening.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download