This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Presyrinx consists of reversible spinal cord swelling without frank cavitation, as observed on T2 weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The condition may evolve into syringomyelia, but timely surgical interventions have achieved meaningful results. Here, we report the case of a 27-year-old woman who presented with headache, dizziness, and diplopia 2 months after suffering a mild head trauma. On MRI, hydrocephalus, downward herniation of the cerebellar tonsil, and a diffuse high signal change in the cervical spinal cord were detected. After insertion of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, her neurological symptoms resolved, and she has had no signs of presyrinx recurrence for >4 years.

Go to :

Keywords: Presyrinx, Syringomyelia, Hydrocephalus, Arnold-Chiari malformation

INTRODUCTION

Presyrinx is defined as reversible spinal cord swelling without frank cavitation, as seen on T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Among the various causes are spinal cord trauma, inflammation, and postinfectious conditions such as arachnoiditis and posterior fossa neoplasm. Presyrinx may evolve into syringomyelia, which leads to irreversible neurological deficits.

3) However, timely surgical intervention can prevent presyrinx progression.

121517)

Here, we report a case of presyrinx associated with post-traumatic hydrocephalus and Chiari I malformation. The patient was treated using a ventricular shunting procedure and has had no neurologic deterioration during >4 years' follow-up.

Go to :

CASE REPORT

A 27-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital from the outpatient department after complaining of headache, dizziness, posterior neck pain, and diplopia. She had no previous medical history or related symptoms. Three months prior to her admission, she had been involved in a car accident, hitting an oncoming vehicle while driving at low speed. At the time of the accident, she did not feel that she required medical attention. However, she subsequently developed symptoms of headache and dizziness as well as posterior nuchal pain worsened by rotational motion of her head. She sought treatment at another hospital, where she was diagnosed with benign positional paroxysmal vertigo, but her symptoms of headache and dizziness worsened. One week before admission to our hospital, she started to vomit and experienced radiating pain in both upper extremities. On neurological examination, she showed a falling tendency on tandem gait and nuchal rigidity, but her overall muscle strength was normal.

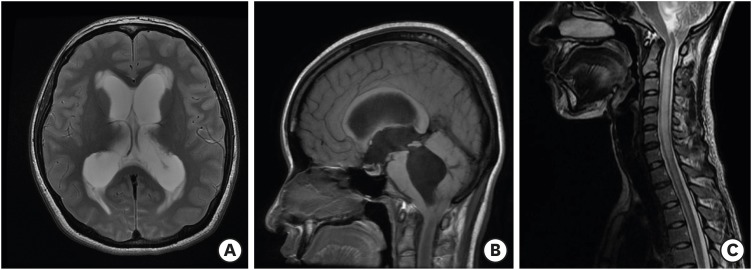

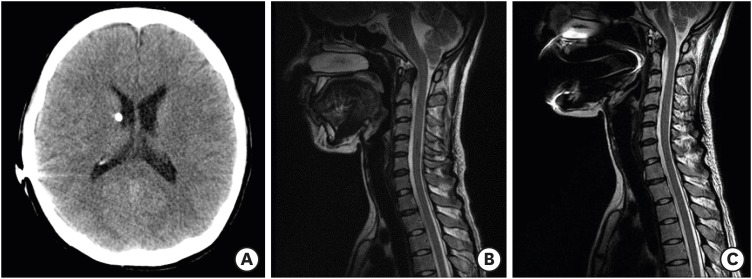

Brain MRI revealed marked hydrocephalus, with dilatation of the entire ventricular system including the fourth ventricle (

FIGURE 1A). The T1 sagittal sections showed a 13-mm downward herniation of the cerebellar tonsil through the foramen magnum, suggesting Chiari malformation type 1 (

FIGURE 1B). Images of her upper cervical spinal cord, which was concurrently included in the MRI, showed dilation and high signal intensity on the T2 sequences. She had no space-occupying or enhanced lesion intracranially, nor did she show any clinical and laboratory signs of infection. To determine the extent and severity of the cervical spinal cord enlargement, she underwent whole-spine MRI with contrast enhancement, which showed that the dilatation extended from C1 to T5, but without cavitation (

FIGURE 1C).

| FIGURE 1

MR images of 27-year-old woman who complained of headache and posterior neck pain after suffering a minor head trauma 2 months earlier. (A) Axial T2-weighted MR image of the gadolinium-enhanced brain shows the dilated lateral ventricles with Evan's ratio of 0.332, with no space-occupying or enhanced lesions in the brain. (B) Sagittal T1-weighted MR image shows dilation of the 4th ventricle and 13 mm downward herniation of the cerebellar tonsil, indicative of a Chiari malformation. (C) Cervicothoracic spinal T2-weighted MR image shows downward herniation of the cerebellar tonsil by 13 mm. An area of T2 prolongation in the dilated cervical spinal cord without frank cavitation is consistent with the radiographic definition of presyrinx, in this case, from C1 to T5.

MR: magnetic resonance.

|

Because her symptoms progressed rapidly, an extraventricular catheter was inserted to relieve the increased intracranial pressure (ICP) from the hydrocephalus and prevent further tonsillar herniation. The ICP measured through extraventricular catheter was 15 cm H

2O at initial insertion, and maintained from 15 to 18 cm H

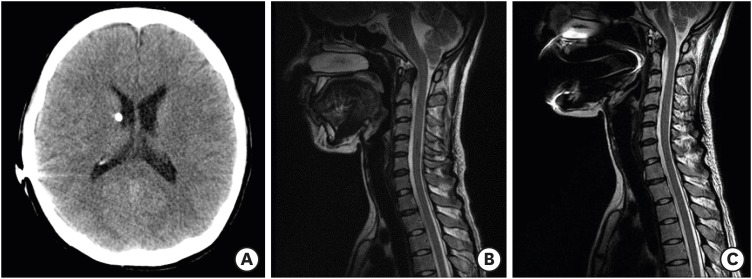

2O afterwards. Hours after the emergency external ventricular drainage, her headache and posterior neck pain started to improve. A permanent ventricular shunting catheter was then implanted to maintain the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) diversion (

FIGURE 2A). The shunting procedure was successful, and no deterioration of symptoms or major complications were observed until her discharge. Cervical MRI performed 8 days after the operation (

FIGURE 2B) showed remarkable improvement of the cervical spinal cord dilatation. On the follow-up images taken 10 months postoperatively (

FIGURE 2C), the abnormal signal intensity had totally disappeared, and the patient was free of neurological impairment. She remained symptom free on a follow-up exam performed 4 years after the operation.

| FIGURE 2 Follow-up images show radiographic improvement after surgical intervention to address the presyrinx with hydrocephalus and Chiari type 1 malformation. (A) Axial brain computed tomography image obtained 7 days after ventriculoperitoneal shunting shows the inserted shunt catheter and the improved status of the hydrocephalus. (B, C) Cervical T2-weighted magnetic resonance images show reduction in the cervical spinal cord swelling at 8 days (B) and 10 months (C) postoperatively. Preoperatively noticed 13 mm downward herniation of cerebellar tonsil was decreased to 11 mm (B) and 9 mm (C), respectively.

|

This case report does not include any information regarding personal identification and therefore is exempt from deliberation of institutional review board. Informed consent was obtained from the patient of abovementioned case report.

Go to :

DISCUSSION

Presyrinx is a reversible myelopathic condition that is defined radiographically as enlargement and T2 prolongation of the spinal cord without frank cavitation.

3) Presyrinx may progress to syringomyelia,

38) but the mechanisms underlying the relationship between presyrinx and syringomyelia with overt cavitation have not been established. However, altered CSF flow dynamics due to a tumor or an arachnoid cyst in the posterior fossa, adhesive arachnoiditis, Chiari malformation, or atlantooccipital dislocation have been implicated.

513)

Cavitation in syringomyelia is classified according to its connection with the ventricular system.

10) In communicating syringomyelia, a blockage of CSF drainage from the ventricular system such as fourth ventricular outlet obstruction, causes fluid collection in the spinal central canal and development of a cyst.

4) In the case of syringomyelia that does not directly connect with the ventricular system, several mechanisms have been proposed. For example, increased spinal subarachnoid pressure may push CSF into the spinal cord via the Virchow–Robin space, inducing cyst formation.

814) Alternatively, in the Greitz-induced Venturi effect, a decrease in the pressure of the CSF as it passes through the constricted region has been proposed to explain the CSF pressure differentiation that drives extracellular fluid into the spinal cord to form a syrinx.

6)

The central spinal canal loses its patency due to aging,

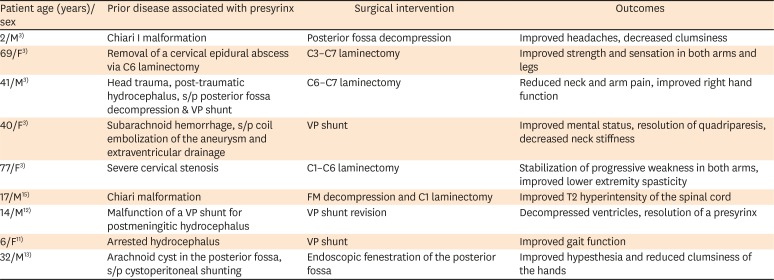

9) allowing fluid to collect, forming a localized edema in the spinal cord parenchyma that gives rise to presyrinx. Several clinical conditions are characterized by abnormal CSF flow dynamics, in which case a timely intervention is needed to restore normal CSF passage (

TABLE 1).

3) Good clinical outcomes have been obtained with surgical decompression, ventriculoperitoneal shunting, and endoscopic fenestration.

3111215)

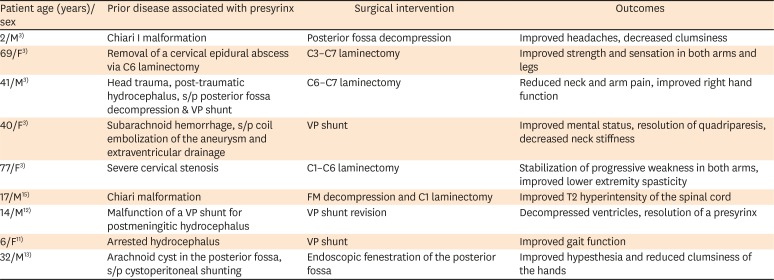

TABLE 1

Reported cases of presyrinx, their surgical interventions and outcomes

|

Patient age (years)/sex |

Prior disease associated with presyrinx |

Surgical intervention |

Outcomes |

|

2/M3)

|

Chiari I malformation |

Posterior fossa decompression |

Improved headaches, decreased clumsiness |

|

69/F3)

|

Removal of a cervical epidural abscess via C6 laminectomy |

C3–C7 laminectomy |

Improved strength and sensation in both arms and legs |

|

41/M3)

|

Head trauma, post-traumatic hydrocephalus, s/p posterior fossa decompression & VP shunt |

C6–C7 laminectomy |

Reduced neck and arm pain, improved right hand function |

|

40/F3)

|

Subarachnoid hemorrhage, s/p coil embolization of the aneurysm and extraventricular drainage |

VP shunt |

Improved mental status, resolution of quadriparesis, decreased neck stiffness |

|

77/F3)

|

Severe cervical stenosis |

C1–C6 laminectomy |

Stabilization of progressive weakness in both arms, improved lower extremity spasticity |

|

17/M15)

|

Chiari malformation |

FM decompression and C1 laminectomy |

Improved T2 hyperintensity of the spinal cord |

|

14/M12)

|

Malfunction of a VP shunt for postmeningitic hydrocephalus |

VP shunt revision |

Decompressed ventricles, resolution of a presyrinx |

|

6/F11)

|

Arrested hydrocephalus |

VP shunt |

Improved gait function |

|

32/M13)

|

Arachnoid cyst in the posterior fossa, s/p cystoperitoneal shunting |

Endoscopic fenestration of the posterior fossa |

Improved hypesthesia and reduced clumsiness of the hands |

Our patient presented with hydrocephalus and Chiari malformation, with a CSF flow disturbance extending to the cervical spinal cord. Post-traumatic hydrocephalus can result from minor head trauma, although its prevalence is lower than that of hydrocephalus resulting from severe head injury.

118) The mechanisms underlying post-traumatic hydrocephalus include blockage of CSF outflow, leptomeningeal fibrosis and arachnoid adhesion.

271819) Whether the minor head trauma suffered by our patient also resulted in an intracranial lesion was unclear, as she did not undergo a clinical exam or brain imaging before she was seen at our hospital. However, given that the hydrocephalus had developed a few months after the accident and that our patient was a healthy young woman, it can be confidently attributed to her minor head trauma.

In patients who suffer a minor head or neck trauma, previously asymptomatic Chiari malformations may become symptomatic.

16) Treatment of the hydrocephalus and increased ICP is the primary strategy before decompressive surgery is considered. An important aspect of presyrinx is that the radiological and clinical abnormalities are potentially reversible,

51112) whereas in syringomyelia, a favorable prognosis can be difficult to achieve. Our patient likely already had an asymptomatic Chiari I malformation. The hydrocephalus that resulted from the minor head trauma apparently aggravated the downward tonsillar herniation into the spinal cord, leading to presyrinx formation. In her case, as in similar cases, CSF diversion was highly effective in reversing the presyrinx, and the MRI signal in the spinal cord began to normalize immediately after installation of the ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Our experience suggests that presyrinx can be defined as a reversible spinal cord swelling caused by a pressure difference between the cranial and spinal spaces.

Go to :

CONCLUSION

Presyrinx is a reversible spinal cord swelling and can be found in various circumstances where normal CSF passage is disturbed. Prompt detection and surgical intervention to restore the flow dynamics can improve the clinical course of this disease entity.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download