BACKGROUND

One of the common phrases we hear these days is “I'm totally burned out.” It is an expression usually used when you are utterly tired of doing something or working, and when you need to take a break because it is hard to continue working anymore. One dictionary defines burnout as a “feeling of always being tired because you have been working too hard” [

1]. As can be seen in the definition, burnout occurs when you work. Medically, burnout is defined as “a psychological syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment that can occur among individuals who work with other people in some capacity” [

2]. It is also considered to be one of the long-term negative effects due to occupational stress or occupational fatigue [

34] and is considered to be a special type of occupational stress [

5]. This burnout has an adverse effect not only from the organizational point of view but also on the physical as well as the psychological aspects of each individual. Studies have shown that burnout results in negative organizational effects such as decreased productivity, increased turnover, and increased absenteeism [

678] has a high correlation with depression [

9101112] and causes sleep disorder and deterioration in memory and attention [

1314], leading the workers to feel that their subjective health is not good [

111516]. Burnout is also associated with the development of coronary heart disease and increases the risk of chronic diseases such as diabetes and musculoskeletal disorders [

1718]. It also triggers a negative lifestyle, such as smoking, drinking, and lack of physical activities [

1719] and lowers the quality of life (QOL) [

20].

Because of these various negative effects, the importance of burnout has been gaining attention from people living and working in modern society, and Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) developed by Maslach et al. [

2] is widely used as a tool to assess such burnout. The original MBI gradually evolved, and it is now categorized into 3 types, which are Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS), Maslach Burnout Inventory-Educators Survey (MBI-ES), and Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS), depending on the worker's job. In MBI-GS, which is used for the most general occupational group, the scale consists of 3 sub-scales; exhaustion, cynicism, and professional efficacy. “Exhaustion” means emotional and physical fatigue due to workloads, demands, etc. “Cynicism” means being indifferent or distancing oneself from the work or taking a negative attitude toward the work overall. “Professional efficacy” means satisfaction with one's past and present work achievements and expectations of continued effectiveness at work. Determination of burnout using MBI-GS is such that the higher the scores in the exhaustion and cynicism field and the lower the score in professional efficacy, the higher the degree of burnout is assessed to be [

2]. The validity of the MBI-GS was verified in studies conducted in various European countries [

21], and the validity of the MBI-GS was verified in Korea by Shin translating it into Korean [

22].

However, since MBI-GS is not a scale made for disease diagnosis or screening purposes, no cutoff value is presented. In order to overcome this problem, research was conducted to determine the reference value of MBI by analyzing the population of Germany and the United States. The results showed that the score distribution of the MBI in the German and US populations differed from each other in sub-scales of MBI [

23]. A comparison of past studies on burnout conducted on nurses showed similar MBI scores in Poland and North America, and the MBI scores in the UK and Ireland were lower than those in Poland and North America [

24252627]. These differences are thought to have been caused by demographic differences and the difference in the work environment, the degree of stress, and occupational characteristics among countries. Therefore, in order to identify the degree of burnout through the MBI score in Korea, it is necessary to identify the distribution of the scores and its characteristics with the Korean population. However, although there are a few studies on the distribution and characteristics of MBI in Korea, as far as the author is aware, no studies have been conducted on reference values.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to conduct MBI-GS, which covers the most general types of jobs, and to investigate characteristics according to demographic factors and occupational factors. In addition, the correlations between burnout and work stress, depression, and QOL, which are known to have a significant correlation with burnout are examined; MBI-GS scores by group for each factor are investigated; and the distribution of scores of sub-scales is presented by quartiles.

DISCUSSION

The purposes of this study are first, to investigate the characteristics of MBI-GS according to demographic factors and occupational factors, second, to identify the correlation with factors known to be burnout-related and the MBI-GS score of each group, third, to identify the distribution of scores of each sub-scales by quartiles.

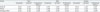

The Cronbach's alpha values of MBI-GS in this study were 0.915, 0.884, and 0.898 for exhaustion, cynicism, and professional efficacy, respectively, for male, and 0.910, 0.856, and 0.808, respectively, for female. When the result was not divided by sex, they were 0.918, 0.871, and 0.893, respectively (

Table 2). The MBI-GS validation study, which was previously conducted by Shin in Korea [

22], showed Cronbach's alpha values of 0.90, 0.81, and 0.86 for exhaustion, cynicism, and professional efficacy, respectively. A study of MBI-GS and health status by Choi [

11], another study conducted in Korea, showed Cronbach's alpha values of 0.856, 0.814, and 0.883 for exhaustion, cynicism, and professional efficacy, respectively. In addition, the MBI-GS validity study by Schutte et al. [

21], a study conducted abroad, showed a Cronbach's alpha value of 0.66–0.86 for each sub-scale. Compared with previous studies in Korea and abroad, MBI-GS used in this study can be said to have a high internal consistency.

When the mean score of MBI-GS was compared according to demographic factors and occupational factors, the results differed by sex (

Table 3). The factors that showed a significant difference in mean scores regardless of sex were age, problem drinking behavior, working time, and working duration in the exhaustion, and age, marital status, working type, and working duration in the professional efficacy. As you can see from the study results, the factors affecting the burnout vary by sex, and the affected sub-scales are also different. There are many studies about factors affecting the burnout like this study. But not every study shows the same results. Previous studies on factors affecting burnout have shown various contradictory results. Maslach et al. [

3], who developed MBI-GS, suggested that these different research results are explained by the fact that social factors play a bigger role in the burnout than individual factors. In other words, people with the same conditions may have different degrees of burnout depending on the country in which they live or their workplaces.

First, the results of ANOVA and post hoc analysis on demographic factors in this study showed that exhaustion score was lower among male in the 50 or older age group than among male in their 30s or 40s, whereas in female, exhaustion score was lower in the 40s and 50 or older than in the 29 or younger age groups. This is thought to be a reflection of the social characteristics of Korea. In Korea, male tend to have higher incomes and greater needs for promotion than female. Year 2018 statistics show a female's employment rate of 57.2%, ranking Korea 28th out of 36 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member countries [

35], and the sex wage gap in Korea was the worst among OECD member countries [

36]. This indicates that in a typical Korean household, male tend to provide the main source of income, which explains the needs described above. And according to a survey by the Korea Research Institute for Vocational Education and Training, new employees in the manufacturing industry will be promoted to manager-level positions in 8.3–8.4 years, taking another 7.6–8.8 years to advance from a manager to a director level, and another 5.9–6.0 years from a director level to an executive level [

37]. Therefore, when promotions are determined, those in their 30s and 40s feel a huge emotional burden, which results in higher scores for exhaustion compared to 50 or older. When they are in their 50 or older, they have a higher position in the company, the work volume reduces, and they have more feeling of security and familiarity with the workplace, leading to lower scores for exhaustion. On the other hand, considering the social characteristics of Korea that the employment rate of female is lower and the household burden of middle-aged female is greater than male, survival bias —i.e., female with a higher degree of burnout resign at an early age because of childbirth or child raising—can be a reason why degree of burnout is not higher among those in their 40s and 50s than among those in the 29 or younger group.

In professional efficacy, for both male and female, every other age groups shows higher scores than 29 or younger age group in post hoc analysis. It can be thought that as they work for a longer period, they become more familiarized with work. In the analysis result on marital status, married male had significantly higher scores in professional efficacy than unmarried male. And unmarried female had higher scores for exhaustion and cynicism and lower scores for professional efficacy. In other words, both unmarried male and female showed a higher degree of burnout, and such results are shown to be relatively consistent among various studies on burnout as suggested by Maslach et al. [

3].

Although previous studies have reported that burnout leads to a negative lifestyle [

1719] and problem drinking behavior was significant in some groups in this study, regular leisure activities and smoking status did not significantly affect the degree of burnout. Those results are thought to be that categorizations of life styles were too simple. Analysis of burnout by sex showed that the degree of burnout was significantly higher among female in all sub-scales. Considering the existing ideas of occupational stress being the key reason for burnout, it can be thought that female have more occupational stress than male. The development and standardization research on KOSS showed similar results. In the reference values presented by development and standardization research on KOSS, in the case of the same quartile, female tended to show higher KOSS scores than male [

27]. In addition, results from previous studies reporting that female are more vulnerable to stress than male support the result of the present study [

383940].

The results of the occupational factors showed significant differences in professional efficacy in the case of working type. The day-fixed worker showed higher professional efficacy than the shift or other worker regardless of sex. And exhaustion score of day-fixed worker was higher than shift or other worker only in female. In working time, exhaustion score showed significant differences in every group for male in post hoc analysis. As working time increased, exhaustion score also increased. And female showed significant differences between 40 or less group and 41–50 group in exhaustion score and cynicism score in post hoc analysis. Both male and female showed no significant difference in professional efficacy. In working duration, statistically significant scores of each sub-scale were lower in the 12 months or less group only except exhaustion score of female in post hoc analysis. This is probably affected by the age distribution of each group. According to the analysis, the age distribution of the groups with a working duration of 12 months or less was 48.7%, 26.1%, 18.5%, and 6.7%, respectively in the given order of age group, and as shown above, burnout is not as severe in the 29 or under age group as among those in their 30s or 40s in male. But female showed higher exhaustion score in 29 or under age group and that's the reason why there is different result only in exhaustion score of female in working duration. And workers in the 12 months or less working duration group are expected to have a relatively low sense of responsibility and pressure because of the distribution of workers in the job placement, takeover, and training process. The low score for professional efficacy is also explained by the fact that workers in the job placement, takeover, and training courses are not yet proficient at their work. In the occupational distribution category, there was a significant difference in professional efficacy regardless of sex. For male, professional efficacy score showed significant difference only between elementary workers and clerks in post hoc analysis. For female, professional efficacy score showed significant differences between elementary workers and craft and related trades workers and between craft and related trades workers and equipment, machine operating, and assembling workers in post hoc analysis. In previous abroad studies, it has been reported that blue-collar workers showed higher levels of cynicism and lower levels of professional efficacy than white-collar workers [

21], but there was no remarkable result in this study maybe because categorization of occupation group is too specific and distribution of occupation is too uneven. It is thought that further investigation may be required for studying burnout by each occupation group.

Mean scores (±standard deviation) were 18.9 (± 7.1), 11.1 (± 4.9), and 27.4 (± 6.4) for exhaustion, cynicism, and professional efficacy, respectively (

Table 3), when calculated without differentiating between sex or factors. In the results of abroad studies, the mean of the MBI-GS for each sub-scales in the Finnish population was 7.6 (± 7.0), 4.9 (± 6.1), and 23.4 (± 10.1) [

21], and 9.7 (± 7.1), 6.7 (± 5.3), and 28.2 (± 5.5) for the Norwegian population [

41]. For Germans, the results were 11.5 (± 6.8), 7.6 (± 5.0), and 25.3 (± 5.3), and for the Greek population, 16.0 (± 7.4), 12.0 (± 5.7), and 28.9 (± 6.4) [

42]. If the results of the present study are compared with the results of the above abroad studies, Koreans have a higher level of exhaustion and cynicism than the Finnish, Norwegian, and German populations and similar levels to the Greek population. Scores for professional efficacy were higher in Korea than in Finland and Germany, but lower than those of Norway and Greece. In particular, when compared with Norwegians, Koreans had higher scores for exhaustion and cynicism but lower scores for professional efficacy. In the case of Greece, their scores were higher in exhaustion and cynicism than those of Finland, Norway, and Germany, and the scores were actually similar to Korea's. The reason for these different results even within Europe is that, since the research in Greece was published in 2012, it reflects the impact of the Greek financial crisis in 2010. In the study conducted in China, belonging to the Asian region, the mean was 7.2 (± 5.5), 3.6 (± 4.3), and 24.4 (± 10.8), respectively [

43]. Compared with all the results from abroad, it can be seen that exhaustion and cynicism tend to be severe in Korea.

In order to verify the concurrent validity of MBI-GS, we used 3 factors that were found to be significantly related to burnout in domestic and abroad studies (

Table 4). Correlation coefficients respectively calculated from the correlation analysis ranged from −0.122 to 0.592. The lowest correlation coefficient was obtained in the correlation analysis of professional efficacy and occupational stress in female (r = −0.122), and the highest correlation coefficient was obtained in the correlation analysis of exhaustion and depression in total (r = 0.592). In the previous studies, Wu et al.'s research [

44] on burnout and occupational stress showed that, as a result of correlation analysis between each sub-scale of MBI and each field of occupational stress inventory (role overload, role insufficiency, role ambiguity, role boundary, etc.) the correlation coefficients were in the range of 0.197–0.418. In addition, in research on police officers, Rothmann [

45] showed a correlation coefficient of 0.17–0.28 as a result of correlation analysis between each sub-scale of the MBI and that of the Police Stress Inventory. The correlation coefficients between sub-scales of MBI-GS and KOSS-SF analyzed in this study were −0.122–0.565. In Valente et al.'s study [

46] of burnout and depression, correlation analysis of each sub-scale of MBI with PHQ-9 showed a correlation coefficient of 0.28–0.59. In addition, the correlation coefficient with MBI was 0.27–0.44 when the BDI was used as a measure of depression [

4748]. The correlation coefficients between sub-scales of MBI-GS and PHQ-9 analyzed in this study were −0.160–0.592. In addition, in Aytekin et al.'s research [

49], the correlation analysis of each sub-scale of MBI and that of WHOQOL-BREF demonstrated a correlation coefficient of 0.283–0.570. In the study using Health Related Quality of Life as a measure of QOL, the correlation coefficient was 0.222–0.537 [

50]. The correlation coefficients between MBI-GS and WHOQOL-BREF in this study were −0.256–0.506. Comparing results of this study with other results, correlation coefficients of professional efficacy of this study tend to similar or lower than other studies and correlation coefficients of exhaustion and cynicism tend to higher than other studies. As a result, in this study population, professional efficacy was the least correlated with other scales. It is thought that this result came from occupational distribution of study population. The largest proportion of occupational distribution is elementary worker in this study. Elementary worker usually perform the same tasks repeatedly and are likely to get used to them. It is thought that's the reason why there is relatively small difference in score of professional efficacy and result in the least correlation.

When the mean of MBI-GS was compared after categorizing KOSS-SF, PHQ-9, and WHOQOL-BREF, the mean value of MBI-GS for groups with higher occupational stress tended to increase, with more depressive moods and with lower QOL, and the difference in the mean score was statistically significant in all groups (

Table 5–

7). In all factors, when male and female were compared in the same group, female tended to have higher mean scores in exhaustion and cynicism and lower scores for professional efficacy than male.

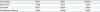

When sub-scales' score of the MBI-GS were divided into quartiles, female tended toward higher scores in exhaustion and cynicism and lower scores in professional efficacy than male. When the mean of MBI-GS according to sex was compared previously (

Table 8), female showed higher scores in all individual sub-scales than male. Referring to the quartiles presented in this study, not only can we check the burnout level of workers when checking MBI-GS results of any worker, but also check the degree of contribution of a specific sub-scale to burnout, helping to identify the main cause of burnout.

There are some limitations to this study. First, there are no questions on income and education level in the survey. Therefore, we could not obtain information about burnout according to income and education level in this study group. Second, the occupational distribution of the subjects is not wide-ranging enough. Although all of the study participants' jobs belonged to the category of MBI-GS, 64% of all participants belonged to the category of elementary workers. Finally, even though the geographical location of the workplace is different, essentially the workers belong to the same company. Job demands, interpersonal conflicts, organizational climate, etc., may be different for each workplace, but reward, organizational system, and job insecurity may be similar because they belong to the same company. Despite these limitations, this study is meaningful in that it presents the characteristics of MBI-GS according to the demographic factors and occupational factors for large-scale population in Korea. Furthermore, we used 3 factors to verify the concurrent validity, and, in particular, the merit of our study is that we used the job stress measurement tool developed in Korea to truly reflect the actual situation of job stress in Korea.

In order to overcome these limitations, additional surveys and research on MBI-GS will be needed for a wider range of occupations and for subjects belonging to different companies. In addition, as we have seen in this study, further studies are required to identify the reason for differences between the MBI-GS scores in Korea and those of other countries and to find out what kind of impacts those differences have on organizations and individuals. It is also important to examine the costs incurred by burnout; recognize the seriousness of the matter; and investigate further which sub-scale of burnout requires interventions, what kind of interventions are required to resolve the issues, and whether those interventions make real differences according to survey results.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download