In Korea, mumps vaccine was introduced during the early 1980s and was included in the National Immunization Program as a combined MMR vaccine in 1985 [

5910]. Since 1997, 2-dose MMR vaccination at 12–15 months and at 4–6 years of age was recommended [

5910]. After introduction of universal vaccination of mumps and MMR, the incidence of mumps dramatically declined [

1511]. However, multiple mumps outbreaks have occurred worldwide among highly vaccinated populations [

1511]. In Korea, the incidence rate of mumps outbreaks has steadily increased since 2007, with a sharp rise in 2013 [

5].

Vaccine effectiveness has been reported in several studies. After the first dose, vaccine effectiveness for the Jeryl Lynn strain vaccine ranged from 72.8% to 91%; Urabe strain vaccine, 54.4% to 93%; and Rubini strain vaccine, ~33% [

512]. The effectiveness of the second MMR vaccine dose was greater than that of the first dose [

511]. However, the actual effectiveness in outbreaks settings was 64–66% for the primary dose and 83–88% for the second doses of the Jeryl Lynn strain vaccine [

511]. MMR vaccines containing the Rubini strain have the lowest efficacy (0–33%), and numerous outbreaks occurred worldwide after the introduction of the Rubini strain vaccine [

511]. Thus, the Rubini strain vaccine was discontinued according to the recommendation by the World Health Organization in 2002 [

591011]. Accordingly, MMR vaccines containing the Rubini strain were withdrawn in Korea during 2002 [

510]. Considering that the Rubini strain vaccine was used in Korea from 1997 to 2002, individuals born during 1991–2001 could have been vaccinated at least once with the Rubini strain vaccine and might be considered susceptible individuals [

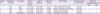

511]. In this study, the seropositivity rate of mumps was 77.1%. Age-specific seroprevalence rates were as follows: 20–29 years, 80%; 30–39 years, 85.2%; 40–49 years, 64.3%; and ≥50 years, 66.7%. The seroprevalence of mumps among the Korean population are insufficiency [

5]. In the previous study, the seroprevalence mumps of young Korean soldiers was 81.1% in 2010 [

13]. In the report of the National Immunization Survey conducted by the National Institute of Health in 2002, the seropositivity rate of mumps was about 80% in the youth over 9 years [

14]. It was impossible to analyze the effect of the use of Rubini strain vaccine on the seropositive rate of mumps [

14]. In this study, HCWs who were born between 1991 and 2001 who were expected to have vaccinated at least once with the Rubini strain vaccine were more seropositive than the rest (87.5%

vs. 74.0%,

P = 0.688). On the other hand, the seropositivity rate for the mumps virus in males was significantly lower than that in females (50.0%

vs. 83.9%,

P = 0.007). Moreover, the seropositivity rate in HCWs aged ≥40 years was lower than that in HCWs aged <40 years; however, this difference was statistically non-significant (65.2%

vs. 83.0%,

P = 0.096). Males were considered to have lower seropositivity rates than females owing to their older age. Here, the proportion of males aged ≥40 years was higher than that of females (57.1%

vs. 26.8%,

P = 0.031). Some studies conducted in the United Kingdom and Europe revealed lower vaccine effectiveness in those who received MMR vaccine more than 10 years before the outbreak and higher incidence rates of mumps with increasing time since vaccination [

45]. Thus, seropositivity rates are closely related to the elapsed time since vaccination rather than the vaccine strain. According to the adult immunization schedule recommended by the Korean Society of Infectious Disease, 2012, new HCWs under the age of 40 years were recommended additional MMR vaccination without any evidence of immunity [

7]; however, there are no guidelines for existing HCWs. In our study, seropositivity of mumps virus was lower in subjects aged ≥40 years than in those aged <40 years. Therefore, a review of the immunization guideline established in 2012 as well as the creation of a new immunization guideline for existing HCWs is required.

Thirty-four (62.9%) of 54 seropositive HCWs and seronegative HCWs received MMR vaccines as PEP. No additional mumps cases occurred during the maximum incubation period. Unlike measles, the mumps vaccine as PEP is not effective in preventing infection [

15]. Nonetheless, MMR vaccine as PEP can be used as an outbreak control measure [

45]. If infection does not occur, the vaccine should boost antibody titers high enough to prevent infection [

5]. If infection occurs, PEP may lead to mild clinical outcomes [

45161718].

This study has some limitations. First, our data were obtained based on a small number of HCWs. Second, the vaccination status verification of mumps among HCWs was not available. Third, our study did not include an unvaccinated control group, since all the eligible HCWs received a postexposure dose of MMR vaccine. Fourth, we could not do the laboratory confirmatory tests of mumps cases, and the specific pathogen of parotitis was not identified. Fifth, there was no definition of MMR vaccine as PEP in mumps outbreak setting and lack of defined previous studies. Finally, since no index patients were identified, HCWs who exposed to the index patients did not receive PEP that fit the definition. Only eligible HCWs were exposed to 4 HCWs with mumps received a single dose of MMR vaccine as PEP.

Eligible HCWs received a MMR vaccine as PEP and no additional mumps cases occurred during the maximum incubation period. PEP was useful in our infection control activities during the mumps outbreak. Therefore, the MMR vaccine as PEP can be considered during the mumps outbreak in a hospital setting.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download