Abstract

Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis (PPP) syndrome is a rare but critical disease with a high mortality rate. The diagnostic dilemma of PPP syndrome is the fact that symptoms occur unexpectedly. A 48-year-old man presented with fever and painful swelling of the left foot that was initially mistaken for cellulitis and gouty arthritis. The diagnosis of PPP syndrome was made based on the abdominal CT findings and elevated pancreatic enzyme levels, lobular panniculitis with ghost cells on a skin biopsy, and polyarthritis on a bone scan. The pancreatitis and panniculitis disappeared spontaneously over time, but the polyarthritis followed its own course despite the use of anti-inflammatory agents. In addition to this case, 30 cases of PPP syndrome in the English literature were reviewed. Most of the patients had initial symptoms other than abdominal pain, leading to misdiagnosis. About one-third of them were finally diagnosed with a pancreatic tumor, of which pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma was the most dominant. They showed a mortality rate of 32.3%, associated mainly with the pancreatic malignancy. Therefore, PPP syndrome should be considered when cutaneous or osteoarticular manifestations occur in patients with pancreatitis. Active investigation and continued observations are needed for patients suspected of PPP syndrome.

Chiari first reported the association of pancreatitis with panniculitis in 1883.1 Pancreatic panniculitis is a rare complication that occurs in approximately 2–3% of patients with pancreatic diseases, mainly pancreatitis.2 Less frequently, these patients may also show polyarthritis, the combination of which is referred to as pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis (PPP) syndrome.3

Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis, the triad of PPP syndrome, can occur synchronously, but one may precede the others. For this reason, panniculitis can be mistaken for erythema nodosum or subcutaneous abscess, whereas joint involvement can be mistaken for septic arthritis, crystal-induced arthropathy, or rheumatoid arthritis.

The prognosis of patients with PPP syndrome usually depends on the underlying pancreatic disorder. A delay in the diagnosis and treatment of the underlying pancreatic disease worsens the clinical outcomes, which can result in a mortality rate as high as 24%.3 This paper reports a case of PPP syndrome that was initially mistaken for cellulitis and gouty arthritis, along with a review of the English literature.

A 48-year-old man presented to the emergency room with a 7-day history of fever and painful swelling of the left foot. The patient also complained of mild epigastric pain that occurred three weeks prior. He had continued to drink alcohol (mean 188 g/day) after suffering from pancreatitis at 18 months earlier. The patient was also a 30-pack-year smoker. He had no history of diabetes or hypertension.

At the time of the initial presentation, the patient had a blood pressure of 110/70 mmHg, pulse rate of 114 beats/min, respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min, and temperature of 38.1℃. Epigastric and periumbilical tenderness were evident upon palpation. The erythematous swelling on the left foot was combined with tenderness and a decreased range of motion. Tender, erythematous nodules were observed in both pretibial regions (Fig. 1).

The laboratory tests showed a white blood cell count of 24,200/µL (reference range, 3,800–10,000), hemoglobin level of 11.9 g/dL (13.3–16.5), platelet count of 205×103/µL (140–400×103), CRP level of 16.871 mg/dL (0.0–0.5), amylase level of >4,500 U/L (30–118), lipase level of >3,500 U/L (12–53), albumin level of 2.6 g/dL (3.2–4.8), AST level of 85 U/L (0–34), ALT level of 16 U/L (10–49), LDH level of 683 U/L (208–378), triglyceride level of 91 mg/dL (0–200), CA 19-9 level of 50.5 U/mL (0–37), and uric acid level of 4.3 mg/dL (3.7–9.2).

CT of the abdomen strongly suggested chronic pancreatitis based on the atrophic changes to the pancreas and dilatation of the main pancreatic duct, but there was no pancreatic calcification (Fig. 2). Thromboses in the portal veins were also visible.

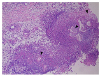

Upon admission, the patient was treated with a combination of ceftriaxone and clindamycin for presumed cellulitis, enoxaparin for portal vein thrombosis, and analgesics. On hospitalization day 6, he complained of painful swelling and tenderness in the second proximal interphalangeal and the fifth metacarpophalangeal joints of the right hand (Fig. 3). The plain radiographs of the right hand revealed soft tissue swelling without bony abnormalities in the second proximal interphalangeal and fifth metacarpophalangeal joints (Fig. 4A). The patient was then treated with colchicine (0.6 mg/day) and a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID; celecoxib 400 mg/day) for presumed gouty arthritis. On hospitalization day 13, a histology examination of a skin biopsy of the left pretibial nodules revealed mostly lobular panniculitis and adipocyte necrosis (“ghost cells”, Fig. 5). Thereafter, such skin lesions in both pretibial areas disappeared spontaneously after several days. On hospitalization day 15, the patient suddenly developed a high fever and became drowsy with labored breathing. After blood culturing, the antibiotic agents were changed to meropenem. Owing to the growth of yeast on the blood cultures, caspofungin was added, which then was changed to fluconazole after the identification of Candida albicans.

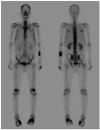

After 21 days of hospitalization, his body temperature, white blood cell count, and pancreatic enzyme levels normalized. On the other hand, the painful swellings of the left foot and right hand were not resolved completely despite the long-term use of colchicine, NSAID, febuxostat (40 mg/day), or low-dose steroid (prednisolone 10 mg/day). On hospitalization day 58, the plain radiographs of the hand showed moth-eaten bone destruction in the base of the second middle and fifth proximal phalanges of the right hand (Fig. 4B). A technetium-99m hydroxymethylene diphosphonate bone scan showed symmetrical uptake in the foot, hand, wrist, and elbow joints (Fig. 6). The blood tests for rheumatoid arthritis were negative. Ultrasound-guided aspiration of the left first metatarsophalangeal joint yielded a dry tap, i.e., failure to aspirate synovial fluid. As a result, samples could not be obtained for analysis. Finally, a diagnosis of PPP syndrome was made based on the chronic pancreatitis on abdominal CT, mostly lobular panniculitis and adipocyte necrosis on a skin biopsy, and polyarthritis on a bone scan. With respect to the treatment of chronic pancreatitis, opioid analgesics were used as needed to control the abdominal pain, and enoxaparin was administered to prevent the progression of portal vein thrombosis. With these conservative treatments, abdominal pain and elevated levels of serum pancreatic enzyme improved gradually. The follow-up CT of the abdomen showed no interval change in pancreatic atrophy, dilatation of the main pancreatic duct, and portal vein thrombosis except for the improvement in peripancreatic necrosis. Intravenous octreotide (1 mg/day) was administered to alleviate the osteoarticular symptoms but was discontinued after three days because it was ineffective. This patient is currently under observation in the outpatient clinic with taking opioid analgesics in place of colchicine, NSAIDs, and steroids to control the joint pain.

English articles published between September 2009 and January 2019 were reviewed using the key words “pancreatitis”, “panniculitis”, and “arthritis”. A total of 30 cases of PPP syndrome were identified in the English literature.4567891011121314151617181920212223242526272829303132 Table 1 lists the clinical characteristics and outcomes of 31 patients with PPP syndrome including the present case.

Of the total 31 patients with PPP syndrome, 23 (74.2%) were male and the median age was 58 years (range, 4–84). At the time of the initial presentation, more than 70% of patients had a chief complaint other than abdominal pain. Arthralgia (71.0%) was the most common symptom, followed by skin lesions (64.5%), abdominal pain (38.7%), and fever (32.3%). Of the 31 patients with PPP syndrome, 10 (32.3%) were initially misdiagnosed as a subcutaneous abscess (four cases), gouty arthritis (two cases), septic arthritis (two cases), cellulitis (one case), compartment syndrome (one case), erythema nodosum (one case), and sepsis (one case).

Of the 13 cases, in which panniculitis type was known, 10 (76.9%) had mostly lobular panniculitis and three (23.1%) had lobular and septal panniculitis. The lower extremities (96.8%) were the most common site of panniculitis, followed by the trunk (22.6%), upper extremities (12.9%), and buttocks (9.7%). Regarding the arthritis type, more than 80% of the patients showed polyarthritis (≥4 joints), which involved mainly the ankle, knee, wrist, hand, and foot joints. No cases involved the simultaneous occurrence of PPP, i.e., the triad of PPP syndrome. In addition, the time sequence of the three conditions varied from case to case, without certain rules.

Of the 31 patients with PPP syndrome, 10 (32.3%) were finally diagnosed with a pancreatic neoplasm, including acinar cell carcinoma (six cases), intraepithelial neoplasm (one case), neuroendocrine tumor (one case), pseudopapillary tumor (one case), and pancreatic tumor of unknown histology (one case). Of these, eight patients had a chief complaint of arthralgia or skin lesions other than abdominal pain at the time of the initial presentation. Overall, 10 (32.3%) out of 31 patients with PPP syndrome died, eight of whom had a pancreatic neoplasm.

This case highlights the challenge in the early diagnosis of PPP syndrome that presented initially with painful joint swelling and then was mistaken for cellulitis and gouty arthritis, resulting in the long-term use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and anti-inflammatory agents. In a review of the literature, the majority of cases of PPP syndrome also had chief complaints other than abdominal pain at the time of the initial presentation, often leading to a misdiagnosis. When a patient with pancreatic disease presents with cutaneous or osteoarticular lesions, a high clinical suspicion of PPP syndrome as well as a differential diagnosis of possible diseases with similar manifestations is needed. In addition, many patients with PPP syndrome are eventually diagnosed with a pancreatic tumor and show a high mortality rate. This suggests that patients with PPP syndrome require careful observation and repeated investigations as needed, not only during treatment but also after recovery.

An early diagnosis of PPP syndrome is difficult when joint involvement or panniculitis dominate with a few symptoms of pancreatitis or vice versa. A delay in the diagnosis and treatment of the underlying pancreatitis can result in significant mortality.3334 In addition, osteoarticular involvement in PPP syndrome can cause permanent destruction, leading to significant morbidity.

The pathogenesis of panniculitis and joint involvement in PPP syndrome is not well known. The most accepted hypothesis is fat necrosis caused by pancreatic lipolytic enzymes.35 In PPP syndrome, subcutaneous fat necrosis causes pancreatic panniculitis, mainly in the lower extremities. The clinical or histology findings of pancreatic panniculitis may vary according to the disease duration. Acute lesions usually appear as subcutaneous nodules (0.5–5 cm in diameter) and histologically lobular panniculitis with necrosis of adipocytes (“ghost cells”), which is pathognomonic for pancreatic panniculitis and is subsequently replaced with granulomatous infiltration over time.2 In this case, a histology examination of the pretibial skin lesions revealed mostly lobular panniculitis and adipocyte necrosis.

Osteoarticular involvement of PPP syndrome includes arthritis, serositis, or periarticular or intramedullary fat necrosis.15 In patients with PPP syndrome, arthritis can come from either periarticular fat necrosis or direct extension from the subcutaneous fat necrosis to the adjacent joint space.36 Most joint involvement is polyarticular, involving mainly the foot, ankle, hand, or wrist joints. Aspiration of the involved joint fluid shows viscous and creamy to yellowish material on the gross appearance, positively birefringent lipid crystals or fat globules with a few cellular components on microscopy, and a high lipid content for cholesterol and triglyceride in a lipid analysis.35 In PPP syndrome, joint involvement usually follows its own course, without any response to treatment with an NSAID, steroid, or immunosuppressant. In this case, the foot, hand, wrist, and elbow joints were symmetrically involved. Aspiration of the involved joint yielded a dry tap with no crystals on microscopy. The pancreatitis and panniculitis improved spontaneously with time, but the polyarthritis waxed and waned regardless of the long-term use of colchicine, an NSAID, a steroid, or octreotide.

In a review of the literature, most patients with PPP syndrome presented with chief complaints other than symptoms of pancreatitis, such as abdominal pain. Therefore, the clinician focused more on the chief complaints rather than considering their association with pancreatitis, making it easier to misdiagnose them as another disorder. In the present case, the patient presented with painful swelling of the left foot that was initially mistaken for cellulitis and then misdiagnosed as gouty arthritis. As a result, the patient was treated with colchicine, an NSAID, and a low-dose steroid for a long time. The findings show that PPP syndrome should be considered when extrapancreatic manifestations, such as arthralgia or skin lesions occur in patients with pancreatitis.

In addition to acute or chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer or pseudocysts may be associated with PPP syndrome.3 In a previous review, the mortality rate of PPP syndrome was high at 24%.3 The review revealed a mortality rate of 30.0%. Interestingly, more than 30% of the patients with PPP syndrome were finally diagnosed with a pancreatic neoplasm, 80% of whom died. In these patients, the pancreatic cancer was more likely to be the underlying cause of PPP syndrome than pancreatitis. In the review, the mortality rate was highest in patients with PPP syndrome who were finally diagnosed with a pancreatic neoplasm, of which pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma was most common. Although pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma accounts for approximately 1% of all pancreatic tumors,37 it is the most common pancreatic neoplasm causing PPP syndrome. Therefore, PPP syndrome can be considered as a surrogate marker for pancreatic diseases with poor outcomes. In addition, patients with long-standing PPP syndrome require careful monitoring for the possibility of pancreatic cancers, such as acinar cell carcinoma.

In conclusion, clinicians should include PPP syndrome in a differential diagnosis when extrapancreatic manifestations, such as osteoarticular involvement or subcutaneous nodules occur in patients with pancreatic disorder(s). Considering the high mortality rate and possibility of a hidden pancreatic malignancy in patients with PPP syndrome, continuous surveillance and active investigation are needed to improve the clinical outcomes.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Gross appearance of the left foot showing erythematous swelling and multiple erythematous nodules in both pretibial regions. |

| Fig. 2Computed tomography of the abdomen demonstrating decreased volume of the pancreas, dilatation of the main pancreatic duct (white arrowhead), and low attenuated lesions with surrounding irregular infiltration in the left anterior pararenal space, suggesting chronic pancreatitis and superimposed peripancreatic necrosis, respectively. |

| Fig. 3Erythematous swelling of the second proximal interphalangeal and fifth metacarpophalangeal joint of the right hand. |

| Fig. 4Plain radiographs of the right hand. (A) On hospital day 6, soft tissue swelling without a bone abnormality in the second proximal interphalangeal and fifth metacarpophalangeal joints (hollow arrowheads) is evident. (B) On hospitalization day 58, moth-eaten bone destruction is visible at the bases of the second middle and fifth proximal phalanges (white arrowheads). |

| Fig. 5Histopathology examination of the lesion showed mostly lobular panniculitis without vasculitis, with adipocyte necrosis (“ghost cells,” black arrowheads) surrounded by neutrophils (H&E, ×100). |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank professor Jin Cheon Kim, MD, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, for proofreading this manuscript.

References

1. Chiari H. Über die sogenannte fettnekrose. Prager Med Wochenschr. 1883; 8:284–286.

2. Requena L, Sánchez Yus E. Panniculitis. Part II. Mostly lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001; 45:325–364.

3. Narváez J, Bianchi MM, Santo P, et al. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010; 39:417–423.

4. Agarwal S, Sasi A, Ray A, Jadon RS, Vikram N. Pancreatitis panniculitis polyarthritis syndrome with multiple bone infarcts. QJM. 2019; 112:43–44.

5. Chattopadhyay A, Mittal S, Sharma A, Jain S. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2018; 09. 27. [Epub ahead of print].

6. Fordham T, Sims HM, Farrant T. Unusual presentation of pancreatitis with extrapancreatic manifestations. BMJ Case Rep. 2018; 2018:bcr-2018-226440.

7. Sondhi AR, Wamsteker EJ, Piper MS. “Doc, I can't walk”-a classic presentation of a rare disease. Gastroenterology. 2018; 155:1703–1705.

8. Fernández-Sartorio C, Combalia A, Ferrando J, et al. Pancreatic panniculitis: a case series from a tertiary university hospital in Spain. Australas J Dermatol. 2018; 59:e269–e272.

9. Graham PM, Altman DA, Gildenberg SR. Panniculitis, pancreatitis, and polyarthritis: a rare clinical syndrome. Cutis. 2018; 101:E34–E37.

10. Zundler S, Strobel D, Manger B, Neurath MF, Wildner D. Pancreatic panniculitis and polyarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2017; 19:62.

11. Dong E, Attam R, Wu BU. Board review vignette: PPP syndrome: pancreatitis, panniculitis, polyarthritis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017; 112:1215–1216.

12. Rao P, Coffman N, Ferreira JP. A diagnostic dilemma in a patient with polyarthritis. Am J Med. 2017; 130:e497–e498.

13. Dieker W, Derer J, Henzler T, et al. Pancreatitis, panniculitis and polyarthritis (PPP-) syndrome caused by post-pancreatitis pseudocyst with mesenteric fistula. Diagnosis and successful surgical treatment. Case report and review of literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017; 31:170–175.

14. Kang DJ, Lee SJ, Choo HJ, Her M, Yoon HK. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis (PPP) syndrome: MRI features of intraosseous fat necrosis involving the feet and knees. Skeletal Radiol. 2017; 46:279–285.

15. Ferri V, Ielpo B, Duran H, et al. Pancreatic disease, panniculitis, polyarthrtitis syndrome successfully treated with total pancreatectomy: case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016; 28:223–226.

16. Loverdos I, Swan MC, Shekherdimian S, et al. A case of pancreatitis, panniculitis and polyarthritis syndrome: elucidating the pathophysiologic mechanisms of a rare condition. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 2015; 3:223–226.

17. Langenhan R, Reimers N, Probst A. Osteomyelitis: a rare complication of pancreatitis and PPP-syndrome. Joint Bone Spine. 2016; 83:221–224.

18. Naeyaert C, de Clerck F, De Wilde V. Pancreatic panniculitis as a paraneoplastic phenomenon of a pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma. Acta Clin Belg. 2016; 71:448–450.

19. Callata-Carhuapoma HR, Pato Cour E, Garcia-Paredes B, et al. Pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma with bilateral ovarian metastases, panniculitis and polyarthritis treated with FOLFIRINOX chemotherapy regimen. A case report and review of the literature. Pancreatology. 2015; 15:440–444.

20. Arbeláez-Cortés A, Vanegas-García AL, Restrepo-Escobar M, Correa-Londoño LA, González-Naranjo LA. Polyarthritis and pancreatic panniculitis associated with pancreatic carcinoma: review of the literature. J Clin Rheumatol. 2014; 20:433–436.

21. Laureano A, Mestre T, Ricardo L, Rodrigues AM, Cardoso J. Pancreatic panniculitis - a cutaneous manifestation of acute pancreatitis. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2014; 8:35–37.

22. Azar L, Chatterjee S, Schils J. Pancreatitis, polyarthritis and panniculitis syndrome. Joint Bone Spine. 2014; 81:184.

23. Kashyap S, Shanker V, Kumari S, Rana L. Panniculitis-polyarthritis-pancreatitis syndrome. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014; 80:352–354.

24. Fraisse T, Boutet O, Tron AM, Prieur E. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, polyarthritis syndrome: an unusual cause of destructive polyarthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2010; 77:617–618.

25. Vasdev V, Bhakuni D, Narayanan K, Jain R. Intramedullary fat necrosis, polyarthritis and panniculitis with pancreatic tumor: a case report. Int J Rheum Dis. 2010; 13:e74–e78.

26. Porcu A, Tilocca PL, Pilo L, Ruiu F, Dettori G. Pancreatic pseudocyst-inferior vena cava fistula causing caval stenosis, left renal vein thrombosis, subcutaneous fat necrosis, arthritis and dysfibrinogenemia. Ann Ital Chir. 2010; 81:215–220.

27. Borowicz J, Morrison M, Hogan D, Miller R. Subcutaneous fat necrosis/ panniculitis and polyarthritis associated with acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a rare presentation of pancreatitis, panniculitis and polyarthritis syndrome. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010; 9:1145–1150.

28. Harris MD, Bucobo JC, Buscaglia JM. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, polyarthritis syndrome successfully treated with EUS-guided cyst-gastrostomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010; 72:456–458.

29. Mustafa KN, Hadidy A, Shoumaf M, Razzuki SA. Polyarthritis with chondronecrosis associated with osteonecrosis, panniculitis and pancreatitis. Rheumatol Int. 2010; 30:1239–1242.

30. Jose T, Biju IK, Kumar A, et al. 'Pancreatitis, polyarthritis, panniculitis syndrome' (PPP syndrome) plus prolonged pyrexia--a rare presentation of chronic pancreatitis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2009; 28:186–188.

31. Chee C. Panniculitis in a patient presenting with a pancreatic tumour and polyarthritis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009; 3:7331.

32. Kuwatani M, Kawakami H, Yamada Y. Osteonecrosis and panniculitis as life-threatening signs. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010; 8:e52–e53.

33. Park SM. Recent advances in management of chronic pancreatitis. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2015; 66:144–149.

34. Park SM, Lee HS, Kim SY, et al. Clinical characteristics of chronic pancreatitis according to the history of pancreatitis. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009; 53:239–245.

35. Dahl PR, Su WP, Cullimore KC, Dicken CH. Pancreatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995; 33:413–417.

36. Burns WA, Matthews MJ, Hamosh M, Weide GV, Blum R, Johnson FB. Lipase-secreting acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas with polyarthropathy. A light and electron microscopic, histochemical, and biochemical study. Cancer. 1974; 33:1002–1009.

37. Klimstra DS, Heffess CS, Oertel JE, Rosai J. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas. A clinicopathologic study of 28 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992; 16:815–837.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download