This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

The goal of the present study was to test the reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Quality of Life after Brain Injury (QOLIBRI) scale. Correlations between the QOLIBRI and Glasgow Coma Scale scores, anxiety, depression, general quality of life (QOL), and demographic characteristics were examined to assess scale validity. The structure of the QOLIBRI was investigated with exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, as well as the Partial Credit Model. Test–retest reliability was assessed over a 2-week interval. Participants were 129 patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) recruited from rehabilitation centers in Japan. The QOLIBRI showed good-to-excellent internal consistency (Cronbach's α: 0.82–0.96), test–retest reliability, and validity (r = 0.77–0.90). Factor analyses revealed a 6-factor structure. Compared to an international sample (IS), Japanese patients had lower QOLIBRI scores and lower satisfaction in several domains. There were positive correlations between the QOLIBRI scales and the Short Form 36 Health Survey (r = 0.22–0.41). The Japanese version of the QOLIBRI showed good-to-excellent psychometric properties. Differences between JS and IS may reflect sampling bias and cultural norms regarding self-evaluation. The QOLIBRI could be a useful tool for assessing health-related QOL in individuals with TBI.

Highlights

• To test the reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Quality of Life after Brain Injury (QOLIBRI) scale.

• Structure of QOLIBRI investigated with exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses.

• Japanese version of the QOLIBRI showed good-to-excellent psychometric properties.

Keywords: Quality of life, Japanese, Traumatic brain injury, Cognitive dysfunction

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization reported that approximately 1.3 million people die annually in traffic accidents, and that 20 to 50 million sustain non-fatal injuries [

1]. People with traumatic brain injury (TBI) often sustain higher brain dysfunction caused by frontal lobe damage and diffuse axonal injury, including memory dysfunction, executive dysfunction, apathy, and emotional control problems. Depending on environmental and personal factors, individuals may experience different levels of difficulties associated with psychosocial problems. Given that physical impairments are often mild, identifying whether a patient has sustained a TBI can be difficult.

During hospitalization, in which patients have a highly-structured schedule, they may experience some problems in the execution of daily tasks. However, when this structure is not present following hospital discharge, patients may also begin to experience further difficulties associated with behavioral problems, executive functioning, and adapting to their environment. Furthermore, they may also experience the inability to perform activities of which they were previously capable. Thus, patients and their families could endure long-term hardships.

The quality of life (QOL) assessment in patients with severe as well as mild TBI is important not only for the patient's own QOL, but for the family's as well. There are measurement tools used to generally assess health-related quality of life (HRQOL), such as the Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36) [

2]; however, there are not as many customized tools for TBI patients. TBI-specific HRQOL measurements regarding higher brain dysfunction (e.g., the European Brain Injury Questionnaire) [

3] have been developed. However, there are no appropriate tools for assessing disease-specific HRQOL among Japanese people with TBI. Therefore, a convenient TBI-specific HRQOL tool that is logistic, reliable, valid, and stable is needed in Japan.

Von Steinbüchel and colleagues [

4] developed the Quality of Life after Brain Injury (QOLIBRI) scale in 2005. The QOLIBRI is designed for people with TBI and can be applied to community-dwelling individuals. After translation into Japanese, this standardized tool would be useful for Japanese residents to address cross-cultural components. Thus, the present study verified the reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the QOLIBRI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and procedures

Participants were 138 community-based patients with TBI sampled from hospitals, community rehabilitation centers, and support centers for people with cognitive dysfunction. We visited these facilities and asked medical staff closely involved in patient rehabilitation to cooperate in the study. Medical staff agreed to participate, then selected eligible patients via medical records and judged potential participants' ability to cooperate before recruiting them.

Participants were recruited from 2013 to 2016. Inclusion criteria were 1) diagnosis of TBI according to International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision; 2) available Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score (worst 24 hours, sum score of eye opening, best verbal response, and best motor response); 3) between 3 months and 15 years lapsed since injury; 4) aged ≥ 15 years at time of injury; 5) outpatient status; and 6) able to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria were 1) a Glasgow Outcome Score Extended (GOSE) below 3; 2) spinal cord injury; 3) significant current or pre-injury psychiatric history; 4) ongoing severe addiction; 5) inability to understand, cooperate, and answer; and 6) terminal illness. The patients completed the questionnaires at home and returned them via mail.

The patients were from the northern (Hokkaido), eastern (Kanagawa, Shizuoka, Tochigi, and Ibaraki prefectures), central (Aichi, Mie, Gifu, and Toyama prefectures), and western (Nara and Ehime prefectures) regions of Japan. The ethics committee at Fujita Health University approved the study protocol (No. 11-167).

QOLIBRI

The QOLIBRI comprises 37 self-rated items on 6 scales and has 2 sections. The first second measures satisfaction, and the second measures feeling bothered with key aspects of life. The 4 satisfaction scales are “Cognition,” “Self,” “Daily life and autonomy,” and “Social relationships.” “Cognition” (7 items) assesses cognitive problems such as memory, attention, being receptive, expressive speech, and decision-making. “Self” (7 items) assesses energy, motivation, self-perception, physical appearance, and self-esteem. “Daily life and autonomy” (7 items) captures independence, activities of daily life, and participation in social roles. “Social relationships” (6 items) covers relationships with friends, family, and partners.

The second part includes 2 scales. “Emotions” (5 items) measures feelings of depression, anxiety, loneliness, boredom, and anger. “Physical problems” (5 items) measures physical problems such as clumsiness, pain, and sensory impairment.

Items are self-rated on 5-point Likert-type scales (not at all, slightly, moderately, quite, and very). Percentage scores can be calculated from 0 to 100. Prior to this study, to develop the Japanese QOLIBRI, 3 native Japanese medical professionals translated the English version of the QOLIBRI into Japanese. The 3 translations were integrated into one version which was then back-translated by one native English speaker from Japanese into English. Discrepancies were harmonized through examination of the 4 translated versions by a harmonization group and the members of the QOLIBRI task force. The most appropriate Japanese wording was selected for the Japanese QOLIBRI items to retain cultural meaning and nuances in the QOLIBRI items.

Baseline assessment

Sociodemographic variables were also investigated. Medical staff collected clinical data, including level of consciousness after injury (using the GCS, where 3–8: severe, 9–12: moderate, and 13–15: mild TBI) [

5]. The GOSE [

6] measured functional disability (3–4: severe disability; 5–6: moderate disability; 7–8: good recovery). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [

7] assessed anxiety and depression with 7 items each. A score greater than 8 indicates probable morbidity [

8]. The SF-36 (ver. 2) measured patient-reported generic health outcomes. Scores are summarized as 3 summary scores: physical component summary (PCS), mental component summary (MCS), and role component summary (RCS). RCS is valid for interpreting SF-36 scores among Japanese residents [

9101112].

Internal consistency for each QOLIBRI domain was assessed with Cronbach's α, with the lower boundary α > 0.70. Test–retest reliability was tested over a 2-week interval with 61 randomly selected participants from the first year of this study. Intraclass correlation (ICC) coefficients were calculated.

Construct validity

Statistical correlations between QOLIBRI domains and GOSE, HADS, and SF-36 scores were examined via Spearman's rank correlation coefficients. Moderate-to-high correlations (≥ 0.4) indicated good construct validity.

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with promax rotation confirmed the QOLIBRI's dimensionality and structure; 6 factors were extracted. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) calculated various statistics for overall fit. The observed variables in the CFA corresponded to the QOLIBRI's individual items and latent variables to factors representing the 6 QOLIBRI subscales. Model fit was evaluated using Chi-square statistics, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). RMSEA < 0.08 represents an acceptable fit, CFI > 0.97 a close fit, and SRMR < 0.1 an acceptable fit. The Japanese sample (JS)'s scores were compared with ISs published in von Steinbüchel et al. [

1314] Using a model based on Item Response Theory, the Partial Credit Model (PCM) [

15] was applied.

Data analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS 24.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and R 3.3.2 including the R-packages psych, eRm, and lavaan (R Core team, Vienna, Austria). If fewer than one-third of items (per subscale) were missing, QOLIBRI data were imputed per participant by substituting the scale mean according to the scale's scoring method [

16].

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics

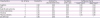

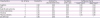

A total of 129 participants with TBI from Japan were enrolled in this study. Nine of the original 138 participants were excluded because 5 patients did not return their questionnaires and, in 4 questionnaires, more than one-third of the items had missing responses. The average participant age was 41.77 years (

Table 1). The average time after TBI was 3,126.3 days. The causes of participants' TBI included traffic accidents, falls, and other incidents.

Table 1

Sociodemographic variables and clinical characteristics of the sample

|

Characteristics |

Category |

No. (%) |

|

Sex |

Female |

25 (19.4) |

|

Male |

104 (80.6) |

|

Marital status |

Single |

61 (47.3) |

|

With partner |

56 (43.4) |

|

After partner |

11 (8.5) |

|

Missing data |

1 (0.8) |

|

Living arrangement |

Independent |

63 (48.8) |

|

Supported |

65 (50.4) |

|

Missing data |

1 (0.8) |

|

Employment |

Full-time |

36 (27.9) |

|

Other |

87 (67.4) |

|

Missing data |

6 (4.7) |

|

Self-reported health status |

Healthy |

80 (62.0) |

|

Unhealthy |

47 (36.4) |

|

Missing data |

2 (1.6) |

|

Major lesion |

None |

9 (7.0) |

|

Focal |

54 (41.9) |

|

Diffuse |

56 (43.4) |

|

Missing data |

10 (7.8) |

|

Time since injury (yr) |

< 1 |

10 (7.8) |

|

1–2 |

13 (10.1) |

|

2–4 |

16 (12.4) |

|

> 4 |

66 (51.2) |

|

Missing data |

24 (18.6) |

|

Health status |

Allergies |

58 (45.0) |

|

Asthma |

9 (7.0) |

|

Trouble smelling |

27 (20.9) |

|

Trouble seeing |

38 (29.5) |

|

Trouble hearing |

9 (7.0) |

|

Thyroid problem |

4 (3.1) |

|

Diabetes |

13 (10.1) |

|

Sleeping disorder |

30 (23.3) |

|

Headache |

48 (37.2) |

|

Nervousness |

48 (37.2) |

|

Depression |

28 (21.7) |

|

Lack of energy |

35 (27.1) |

|

Lack of physical strength |

52 (40.3) |

|

Back problems |

14 (10.9) |

|

Arthritis |

13 (10.1) |

|

Problem with movement (TBI) |

58 (45.0) |

|

Problem with movement (not TBI) |

26 (20.2) |

|

Paralysis (TBI) |

38 (29.5) |

|

Paralysis (not TBI) |

9 (7.0) |

|

Amputation |

2 (1.6) |

|

High blood pressure |

11 (8.5) |

|

Heart failure |

3 (2.3) |

|

Angina |

2 (1.6) |

|

Heart attack |

1 (0.8) |

|

Pacemaker |

0 (0.0) |

|

Inflamed bowel, colitis |

1 (0.8) |

|

Ulcer |

3 (2.3) |

|

Kidney disease |

0 (0.0) |

|

Cancer |

0 (0.0) |

|

GOSE |

Severe |

56 (43.4) |

|

Moderate |

53 (41.1) |

|

Good recovery |

18 (14.0) |

|

Missing data |

2 (1.6) |

|

GCS (worst 24 hr) |

Severe |

101 (78.3) |

|

Moderate |

13 (10.1) |

|

Minor |

12 (9.3) |

|

Missing data |

3 (2.3) |

|

HADS—Anxiety |

Normal |

71 (55.0) |

|

Morbidity |

54 (41.9) |

|

Missing data |

4 (3.1) |

|

HADS—Depression |

Normal |

53 (41.1) |

|

Morbidity |

72 (55.8) |

|

Missing data |

4 (3.1) |

Frequency analyses

The number of individuals that achieved each score was measured, with 2 adjacent response categories summed; a sum lower than 10% of all responses indicated a frequency problem [

17]. The following items showed frequency problems in categories 4 (quite) and 5 (very): for “Cognition,” items 6 (“How satisfied are you with your ability to find your way around?”) and 7 (“How satisfied are you with your speed of thinking?”); for “Self,” items 6 (“How satisfied are you with the way you perceive yourself?”) and 7 (“How satisfied are you with the way you see your future?”); and for “Social relationships,” item 5 (“How satisfied are you with your participation in work or education?”). Generally, endorsement of these 5 items was low, with between 1% and 7% of participants choosing categories 4 and 5 (equivalent to between 7% and 9%). Means for each of the items ranged between 1.90–3.86. Means for the 5 items noted above ranged between 1.90–2.51, which was relatively lower than the means of other items.

Floor/ceiling effects were determined to exist if 60% or more of responses were located at the scale's maximum/minimum. With responses located between 1% and 44%, no floor or ceiling effects emerged.

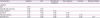

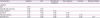

Internal consistency and test–retest reliability

Cronbach's α ranged from 0.82 (“Physical problems”) to 0.92 (“Self”) (

Table 2). ICCs ranged from 0.77 (“Physical problems”) to 0.90 (“Cognition”). ICCs for the other scales were 0.90 (“Self”), 0.86 (“Daily life and autonomy”), 0.83 (“Social relationships”), and 0.82 (“Emotions”) (

Table 2). ICC values greater than 0.75 indicate excellent reliability.

Table 2

Internal consistency (Cronbach's α) and test–retest reliability (intraclass correlations)

|

Characteristics |

No. of items |

Cronbach's α |

Cronbach's α (standardized items) |

Correlation within class |

Confidence interval |

|

Lower bound |

Upper bound |

|

Cognition |

7 |

0.90 |

0.90 |

0.90 |

0.83 |

0.94 |

|

Self |

7 |

0.91 |

0.91 |

0.90 |

0.84 |

0.94 |

|

Daily life and autonomy |

7 |

0.91 |

0.91 |

0.86 |

0.78 |

0.92 |

|

Social relationships |

6 |

0.84 |

0.84 |

0.83 |

0.73 |

0.90 |

|

Emotions |

5 |

0.84 |

0.84 |

0.82 |

0.71 |

0.89 |

|

Physical problems |

5 |

0.82 |

0.82 |

0.77 |

0.64 |

0.86 |

|

QOLIBRI total |

37 |

0.96 |

0.96 |

0.90 |

- |

- |

Psychometric characteristics of the QOLIBRI items

Regarding item characteristics of the QOLIBRI, the skewness and kurtosis values were psychometrically satisfactory to excellent (skewness: 0.03–0.91).

Corrected item total correlations (CITC) examine an item relative to the total score, which indicates whether an item is consistent with the remaining items, and should be ≥ 0.4. All scales were judged to be good to very good (CITC: 0.46–0.80).

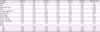

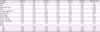

Intercorrelations between the QOLIBRI scales

The QOLIBRI scales showed medium-to-high correlations (r = 0.39–0.88) (

Table 3), indicating that the scales were not independent (e.g., the correlation between “Daily life and autonomy” and “Self” was r = 0.81). These results should be considered in relation to the EFA.

Table 3

Intercorrelations of QOLIBRI scales

|

Characteristics |

Cognition |

Self |

Daily life and autonomy |

Social relations |

Emotions |

Physical problems |

|

Cognition |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Self |

0.77*

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Daily life and autonomy |

0.76*

|

0.81*

|

|

|

|

|

|

Social relations |

0.62*

|

0.65*

|

0.67*

|

|

|

|

|

Emotions |

0.45*

|

0.40*

|

0.39*

|

0.39*

|

|

|

|

Physical problems |

0.53*

|

0.50*

|

0.48*

|

0.43*

|

0.55*

|

|

|

QOLIBRI total |

0.87*

|

0.88*

|

0.88*

|

0.79*

|

0.64*

|

0.71*

|

Table 4 presents correlations between all QOLIBRI scales, covariates, and the SF-36. These correlations were considered significant at p < 0.05. Sex was positively correlated with “Self,” while there were negative correlations between age and “Daily life and autonomy,” as well as between years since injury and “Social relations.” Anxiety and depression each had medium-to-strong negative correlations with all QOLIBRI subscales and the total score. GOSE scores showed small-to-medium correlations with “Cognition,” “Self,” “Daily life and autonomy,” “Physical problems,” and the total score. All QOLIBRI scales had negative medium correlations with living arrangements. Health status had small-to-medium associations with all QOLIBRI scales. Work status had a significant negative correlation with “Daily life and autonomy,” and marital status had a significant positive correlation with “Social relations.” Every QOLIBRI scale, except for “Social relations” and “Emotions,” had moderate correlations with PCS, MCS, and RCS on the SF-36.

Table 4

Relationships between QOLIBRI scales and covariates

|

Variables |

Cognition |

Self |

Daily life |

Social |

Emotions |

Physical |

QOLIBRI total |

|

Gender |

0.15 |

0.21*

|

0.13 |

0.00 |

0.03 |

0.06 |

0.13 |

|

Age |

−0.02 |

−0.15 |

−0.18*

|

−0.08 |

0.15 |

0.02 |

−0.08 |

|

Years since injury |

−0.06 |

−0.05 |

−0.13 |

−0.22*

|

0.04 |

0.02 |

−0.09 |

|

GCS |

−0.09 |

−0.08 |

−0.11 |

0.03 |

−0.01 |

0.03 |

−0.08 |

|

Living arrangements |

−0.39†

|

−0.38†

|

−0.48†

|

−0.41†

|

−0.24*

|

−0.28†

|

−0.46†

|

|

Health status |

−0.19†

|

−0.33†

|

−0.42†

|

−0.21*

|

−0.23*

|

−0.35†

|

−0.36†

|

|

Work status |

−0.05 |

−0.03 |

−0.21*

|

−0.15 |

0.00 |

−0.07 |

−0.11 |

|

Marital status |

−0.03 |

−0.05 |

−0.02 |

0.20*

|

0.13 |

0.12 |

0.03 |

|

HADS—Anxiety |

−0.45†

|

−0.51†

|

−0.38†

|

−0.44†

|

−0.63†

|

−0.49†

|

−0.59†

|

|

HADS—Depression |

−0.58†

|

−0.68†

|

−0.58†

|

−0.51†

|

−0.47†

|

−0.56†

|

−0.71†

|

|

GOSE |

0.21*

|

0.25*

|

0.32*

|

0.15 |

0.13 |

0.25*

|

0.27*

|

|

SF-36 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PCS |

0.22*

|

0.29*

|

0.40*

|

0.17 |

0.12 |

0.43*

|

0.34*

|

|

MCS |

0.29*

|

0.34*

|

0.19*

|

0.32*

|

0.51*

|

0.36*

|

0.41*

|

|

RCS |

0.39*

|

0.32*

|

0.36*

|

0.29*

|

0.27*

|

0.34*

|

0.41*

|

Factor structure

EFA

The EFA demonstrated a factor structure similar to the QOLIBRI's a priori factor structure. Item 6 (navigate) of “Cognition” loaded on “Self,” items 1 (energy) and 2 (motivation) of “Self” loaded on “Daily life and autonomy,” and item 1 (slow/clumsy) of “Physical problems” loaded on “Cognition.” The high item intercorrelations of the subscales revealed dependent factors. All other items were correctly matched. Of the 37 items, 33 converged with loading scores > 0.4 on their corresponding domains from the original QOLIBRI.

CFA

Due to intercorrelations between the 6 factors (r = 0.39–0.88), a second-order HRQOL factor was included [

15]. Subsequently, the final model comprised 6 first-order variables and HRQOL as a second-order latent variable (

Fig. 1). The model fit statistics of the second-order HRQOL model indicated moderate fit (CFI = 0.991; TLI = 0.993; RMSEA = 0.079; SRMR = 0.089; χ

2 = 3,545.715; df = 666; p = 0.000). Infit t-statistics revealed that most scales fitted a PCM. Items with infit t > 2 lack model fit, while items with t < −2 are very predictable. In the satisfaction scales, most item characteristics supported a valid PCM. While item 7 of “Cognition” and items 1 and 6 of “Self” deviated from the Rasch model (infit t = −2.35, −2.15, and −2.40, respectively) in the “bothered” scales, 3 items in “Emotions” (1, 3, and 4) and 2 items of “Physical problems” (2 and 5) differed from the Rasch model (infit t = −2.91, −3.44, −4.96, −2.34, and −2.62, respectively).

| Fig. 1

Confirmatory factor analysis (estimator: diagonal weighted least squares). Moderate fit of the 6 latent factors and a second-order HRQOL factor (0.61–0.94) is indicated.

HRQOL, health-related quality of life.

|

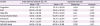

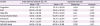

Comparison with IS

Compared with an IS, the study sample had markedly lower means in “Cognition,” “Self,” “Daily life and autonomy,” and “Social relationships.” Our sample showed higher values on the “bothered” scales than on satisfaction; the former were nearly as high as the IS. The difference in QOLIBRI total scores was also remarkable (

Table 5).

Table 5

Comparison of mean scores between the international and Japanese samples

|

Scales |

International sample [1314] |

Japanese sample |

|

Mean ± SD |

Mean ± SD |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

|

Cognition |

61.26 ± 21.77 |

32.15 ± 20.59 |

0.64 |

0.30 |

|

Self |

60.03 ± 21.96 |

32.61 ± 22.94 |

0.38 |

−0.41 |

|

Daily life |

66.41 ± 22.38 |

37.78 ± 24.30 |

0.41 |

−0.29 |

|

Social relationships |

63.65 ± 22.64 |

44.29 ± 22.27 |

0.11 |

−0.23 |

|

Emotions |

71.71 ± 24.69 |

62.17 ± 25.04 |

−0.44 |

−0.41 |

|

Physical problems |

67.91 ± 23.47 |

58.35 ± 25.32 |

−0.36 |

−0.62 |

|

QOLIBRI total |

64.58 ± 18.24 |

42.95 ± 18.68 |

0.29 |

0.31 |

DISCUSSION

The results (test–retest reliabilities assessed with ICCs, internal consistencies, CITC, and scale intercorrelations) revealed good-to-very good psychometric properties for the Japanese version of the QOLIBRI. The EFA revealed a factor structure similar to the QOLBRI's a priori factor structure. Moderate fit of the 6 latent factors and a second-order HRQOL factor was indicated (CFI = 0.991; RMSEA = 0.079; SRMR = 0.089), according to CFA. Infit t-statistics showed that most scales fitted a PCM.

Thus, the Japanese version of the QOLIBRI appears to have high validity and reliability, and is suitable for people with TBI in Japan. The measure demonstrated favorable psychometric properties, regardless of cultural and social differences.

Investigating the GCS did not reveal lower HRQOL among individuals with severely impaired consciousness than those with less severe impairment. As in patients with Alzheimer's dementia, this special group may have self-awareness problems, which may allow patients to rate their HRQOL highly. However, caution is required concerning such an interpretation, because patients appeared to understand the questions. As such, they may have, for example, rated their HRQOL so high because they had survived a life-threatening situation. Additionally, the JS differed strongly on various covariates (e.g., more people had highly severe TBI and severe disability scores based on the GOSE). However, results concerning the GCS splits are comparable to other language validations [

1314].

Younger participants had higher satisfaction in “Self” and “Social relations.” As people age, their range of interpersonal relationships and activities tends to be more limited, and they may have a reduced sense of accomplishment. Sex had no impact on QOLIBRI scores. Being single (marital status) negatively impacted “Social relations.” Whether one has a spouse may influence how well one maintains relationships with family and friends. Being healthy (health status) affected all satisfaction and bothered scales (“Emotions” and “Physical Problems”), as did living arrangements. Patients living independently were more satisfied and less bothered in all domains; a person leading an independent life was likely more confident. GOSE results related strongly with “Cognition,” “Self,” “Daily life and autonomy,” “Physical problems,” and the QOLIBRI total score. Fewer problems with daily life may affect HRQOL. HRQOL barely differed between patients with “severe” and “moderate disability”; however, these 2 groups had much lower HRQOL than the “good recovery” group. The highest QOLIBRI scores in all domains were associated with good recovery. Distinguishing based on the GCS revealed no statistically significant results; however, anxiety and depression (HADS) were strongly associated with all QOLIBRI scales. High anxiety values accompanied the lowest scores on all QOLIBRI subscales and vice versa. Overall, the demographic characteristics and other covariates were significantly associated with HRQOL. These results support the scale's validity. Moderate relationships between the SF-36 and the QOLIBRI items suggests that the QOLIBRI and SF-36 have some overlapping aspects.

Comparisons between the JS and IS showed less satisfaction in the JS than in the IS. All mean scores in each satisfaction subscale were far below the corresponding IS values, especially in “Cognition,” “Self,” and “Daily life and autonomy.” These can be explained by the JS's high severity of TBI: 78.3% vs. 58% in the IS. This discrepancy in severity between the 2 samples may be due to sampling bias. Many participants in the JS had been receiving outpatient rehabilitation services for a significant amount of time, due to various problems associated with higher brain dysfunction. Patients with less severe TBI often experience a good recovery and readjustment to society, and once their rehabilitation programs are complete, they seldom return for follow-up visits. Thus, this may have contributed to a higher number of patients with more severe TBI in the JS. On the GOSE, 43.4% of the JS were diagnosed with severe disability, compared to only 18% in the IS; 14% of the JS had good recovery compared to 28% of the IS. Additionally, more IS respondents felt healthy (IS: 72%; JS: 62%). Fewer people reported being independent in the JS (48.8%) than in the IS (57%). Possible reasons for these discrepancies include patients in the JSs tending to have lower self-esteem than patients in the IS [

18].

Governmental support for people with higher brain dysfunction started in Japan in 2013, when the People with Disabilities Assistance Law was enacted. This assistance system is far from adequate or extensive. Ordinary people often fail to recognize and understand people with higher brain dysfunction. This might lead to self-reported perceptions of not being fully accepted in society, which, in turn, results in lower self-esteem. These factors may have also led to lower scores compared with the IS.

While the present study was limited by the small number of participants and sampling bias, the overall test results suggest that the Japanese version of the QOLIBRI has good psychometric characteristics and, therefore, is a reliable and valid instrument for assessing TBI in the Japanese population. In the future, research should be conducted to create a Japanese short version of the QOLIBRI, as considering fatigue is often experienced by people with TBI, this could be convenient to use in epidemic surveys.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors sincerely thank the rehabilitation staff from the following institutions for their assistance in this investigation: Fujita Health University, Mie Prefecture Physically Handicapped General Welfare Center, Komono Kosei Hospital, Matsusaka Chuo General Hospital, Chubu Medical Center, Kizawa Memorial Hospital, Nagoya City General Rehabilitation Center, Yokohama City University Medical Center, Seirei Mikatahara General Hospital, Matsuyama Rehabilitation Hospital, International University of Health and Welfare Rehabilitation Center, Shimura Ohmiya Hospital, Hoshigaura Hospital, Asuka family support center, Koushi family support center, Waraitaiko support center for people with cognitive dysfunction.

References

2. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992; 30:473–483.

3. Sopena S, Dewar BK, Nannery R, Teasdale TW, Wilson BA. The European Brain Injury Questionnaire (EBIQ) as a reliable outcome measure for use with people with brain injury. Brain Inj. 2007; 21:1063–1068.

4. von Steinbüchel N, Lischetzke T, Gurny M, Eid M. Assessing quality of life in older people: psychometric properties of the WHOQOL-BREF. Eur J Ageing. 2006; 3:116–122.

5. Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974; 2:81–84.

6. Wilson JT, Pettigrew LE, Teasdale GM. Structured interviews for the Glasgow Outcome Scale and the extended Glasgow Outcome Scale: guidelines for their use. J Neurotrauma. 1998; 15:573–585.

7. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983; 67:361–370.

8. Olssøn I, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Rating Scale: a cross-sectional study of psychometrics and case finding abilities in general practice. BMC Psychiatry. 2005; 5:46.

9. Fukuhara S, Suzukamo Y. Manual of SF-36v2 Japanese version. Kyoto: I Hope International Inc.;2004.

10. Suzukamo Y, Fukuhara S, Green J, Kosinski M, Gandek B, Ware JE. Validation testing of a three-component model of Short Form-36 scores. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011; 64:301–308.

11. Fukuhara S, Bito S, Green J, Hsiao A, Kurokawa K. Translation, adaptation, and validation of the SF-36 Health Survey for use in Japan. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998; 51:1037–1044.

12. Fukuhara S, Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Wada S, Gandek B. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity of the Japanese SF-36 Health Survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998; 51:1045–1053.

13. von Steinbüchel N, Wilson L, Gibbons H, Hawthorne G, Höfer S, Schmidt S, Bullinger M, Maas A, Neugebauer E, Powell J, von Wild K, Zitnay G, Bakx W, Christensen AL, Koskinen S, Sarajuuri J, Formisano R, Sasse N, Truelle JL. QOLIBRI Task Force. Quality of Life after Brain Injury (QOLIBRI): scale development and metric properties. J Neurotrauma. 2010; 27:1167–1185.

14. von Steinbüchel N, Wilson L, Gibbons H, Hawthorne G, Höfer S, Schmidt S, Bullinger M, Maas A, Neugebauer E, Powell J, von Wild K, Zitnay G, Bakx W, Christensen AL, Koskinen S, Formisano R, Saarajuri J, Sasse N, Truelle JL. QOLIBRI Task Force. Quality of Life after Brain Injury (QOLIBRI): scale validity and correlates of quality of life. J Neurotrauma. 2010; 27:1157–1165.

15. Masters GN. A Rasch model for partial credit scoring. Psychometrika. 1982; 47:149–174.

17. The WHOQOL group. The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 1998; 46:1569–1585.

18. Schmitt DP, Allik J. Simultaneous administration of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale in 53 nations: exploring the universal and culture-specific features of global self-esteem. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005; 89:623–642.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download