INTRODUCTION

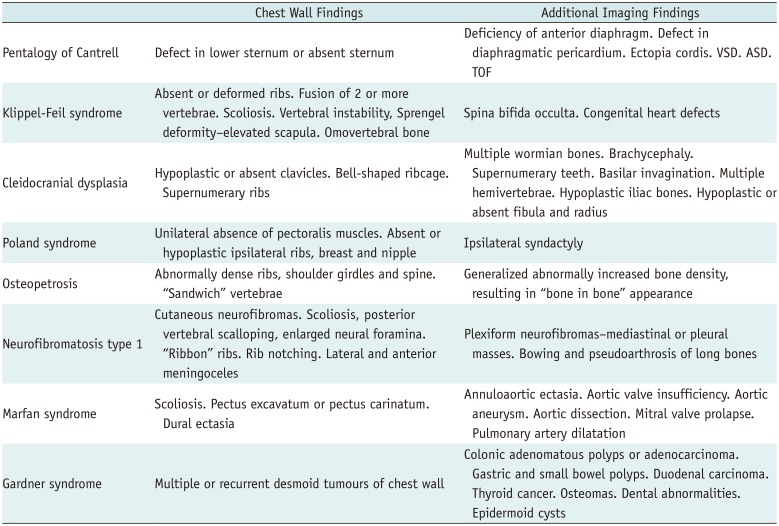

Table 1

Most Common Imaging Findings of Selected Congenital Pathologies with Chest Wall Involvement

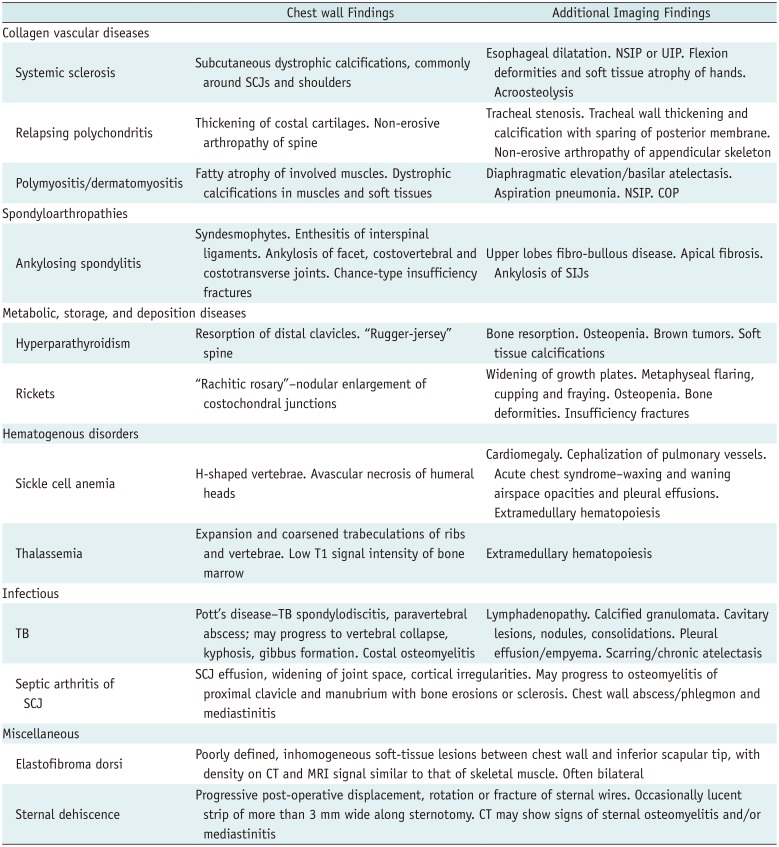

Table 2

Most Common Imaging Findings of Selected Acquired Pathologies with Chest Wall Involvement

Congenital Diseases

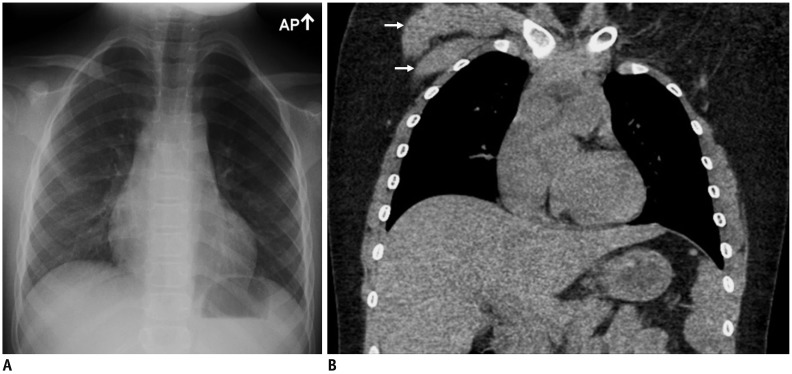

Pentalogy of Cantrell

| Fig. 1Pentalogy of Cantrell.Chest CT scan of 25-year-old male with Pentalogy of Cantrell, status post remote Fontan procedure for complex congenital heart abnormality, shows absence of sternum resulting in partial herniation of right ventricle (arrowheads). Note extracardiac Fontan conduit (arrow), multiple mediastinal collateral vessels, and bilateral pleural effusions.

|

Klippel-Feil Syndrome

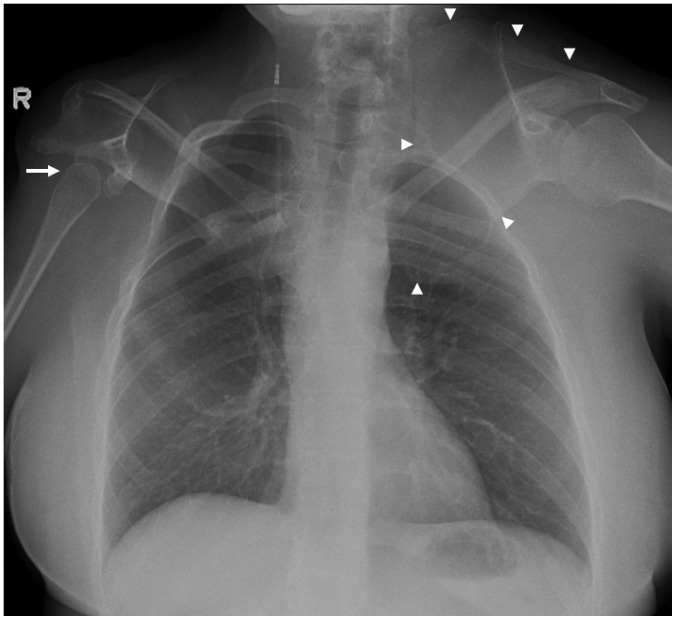

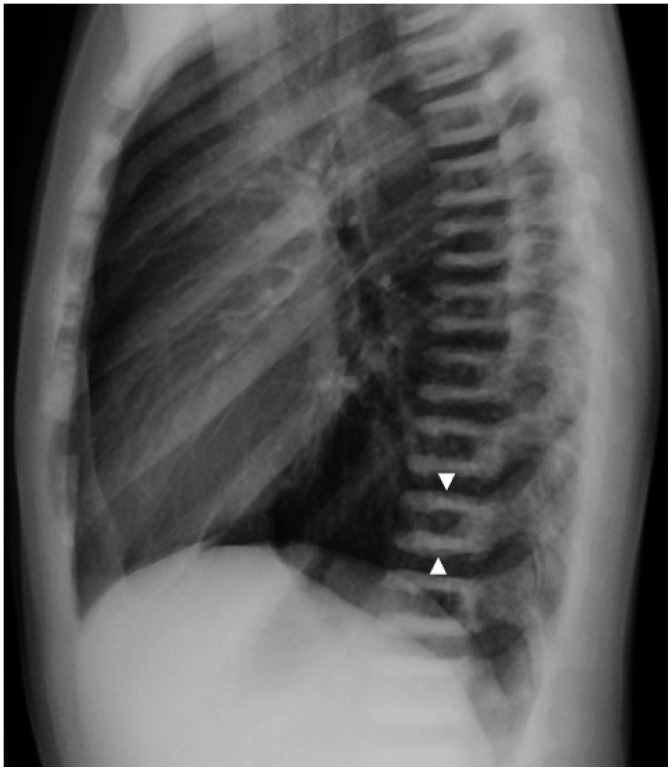

| Fig. 2Klippel-Feil syndrome.Chest radiograph of 39-year-old female with Klippel-Feil syndrome shows hypoplastic right humeral head (arrow), dysmorphic right scapula and glenoid, high-riding left scapula-Sprengel deformity (arrowheads), and multiple upper rib deformities. There is right ventriculo-peritoneal shunt.

|

Cleidocranial Dysplasia

Poland Syndrome

Osteopetrosis

Neurofibromatosis Type 1

Marfan Syndrome

Gardner Syndrome

Acquired Conditions

Systemic Sclerosis

Relapsing Polychondritis

Ankylosing Spondylitis

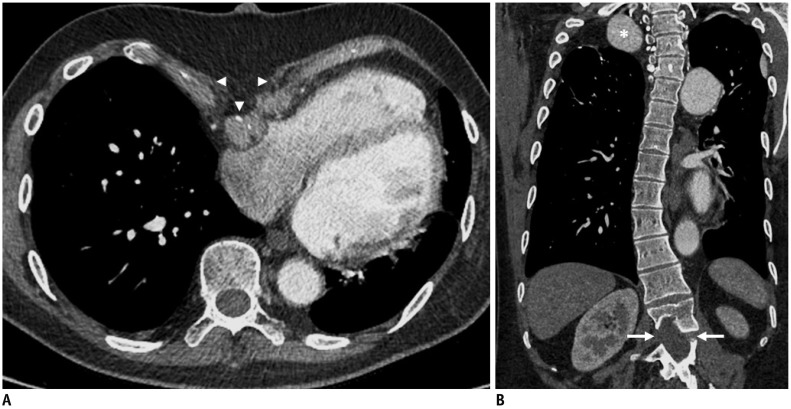

| Fig. 12Ankylosing spondylitis.

A. CT with sagittal reformation in 76-year-old male with ankylosing spondylitis shows diffuse ankylosis of thoracolumbar spine. B. Chest CT with sagittal reformation in different patient with ankylosing spondylitis shows acute Chance fracture in upper lumbar spine (arrow).

|

Polymyositis/Dermatomyositis

Hyperparathyroidism

Rickets

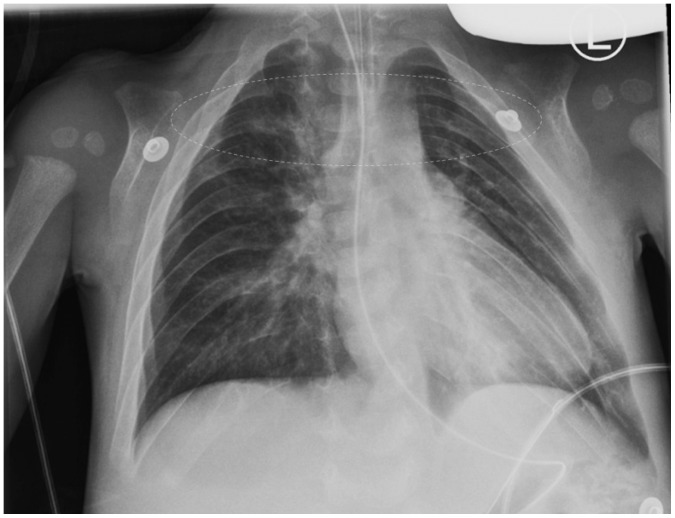

| Fig. 15Rickets.Frontal chest radiograph of 3-month-old premature-born female with rickets demonstrates healing fractures of left posterior 6th and 7th ribs (arrows), nodular widening of bilateral costochondral junctions-rachitic rosary (arrowheads) and fraying of proximal humeral metaphyses (dashed outlines).

|

Sickle Cell Anemia

Thalassemia

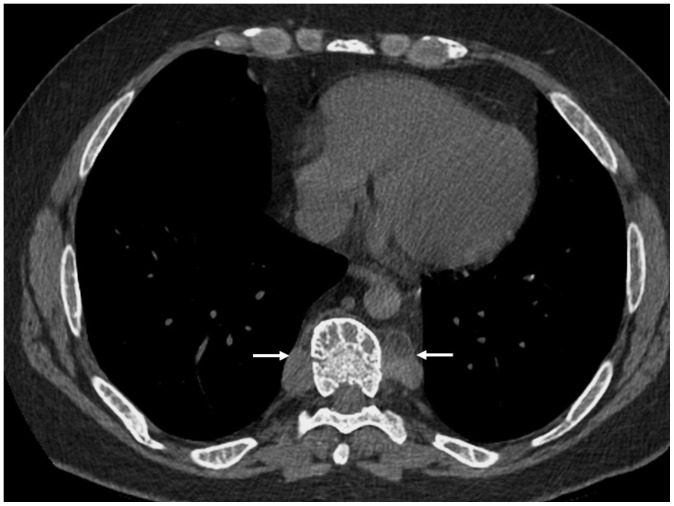

| Fig. 17Beta thalassemia.Chest CT scan of 44-year-old male with beta thalassemia intermedia shows diffuse expansion of osseous medullary spaces, coarsened trabeculations of ribs and vertebrae, and paravertebral extramedullary hematopoiesis (arrows).

|

| Fig. 18Beta thalassemia.Sagittal T1-weighted MRI of spine in 9-year-old male with beta thalassemia major shows diffuse abnormally low signal intensity of bone marrow related to active red marrow and iron deposition from multiple blood transfusions. Note that bone marrow (asterisk) is of significantly lower intensity than intervertebral disks (arrowhead).

|

Tuberculosis

Septic Arthritis of the Sternoclavicular Joint

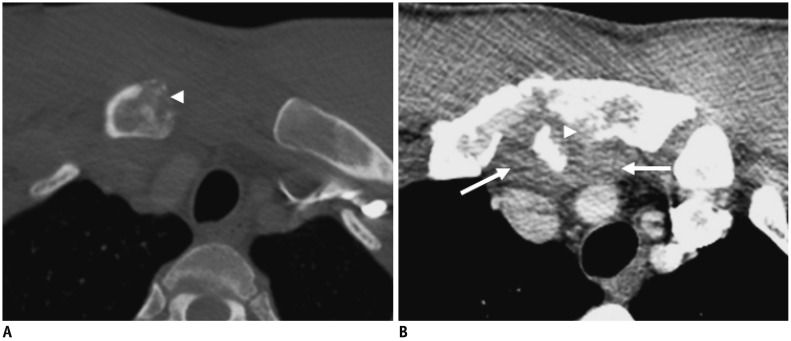

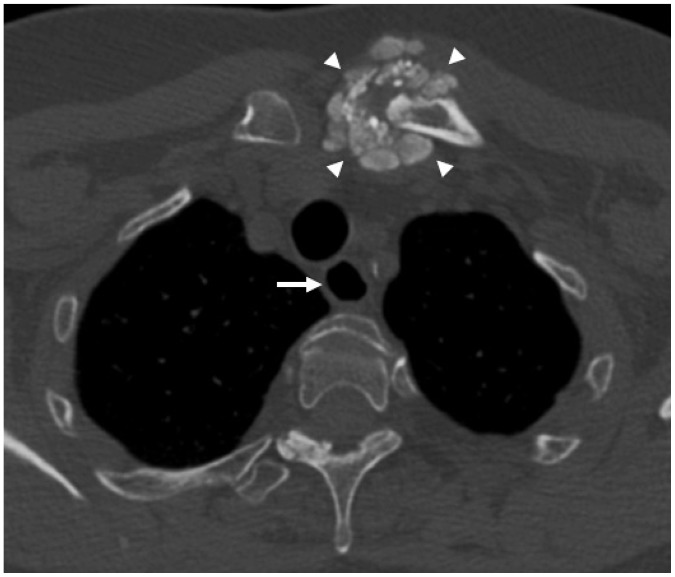

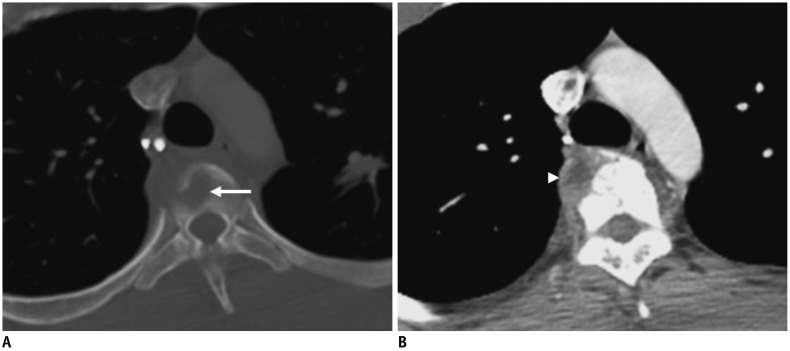

| Fig. 20Septic arthritis of sternoclavicular joint.Chest CT in bone (A) and mediastinal (B) windows of 41-year-old male, who developed septic arthritis of right sternoclavicular joint several weeks following penetrating injury to chest, demonstrates erosive lesions in right clavicular head and manubrium (arrowheads) consistent with osteomyelitis, and adjacent phlegmonous collection (arrows).

|

Elastofibroma Dorsi

Sternal Dehiscence

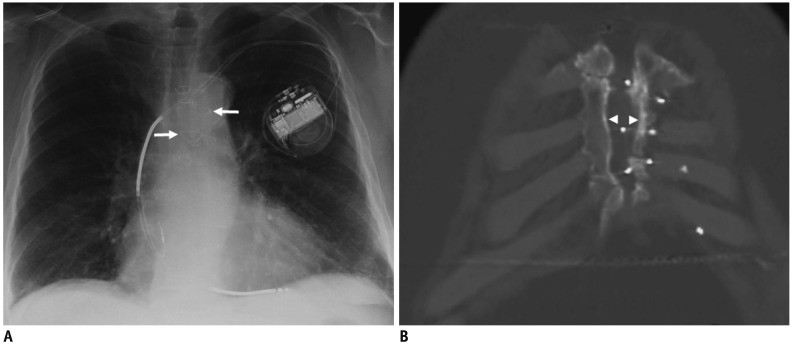

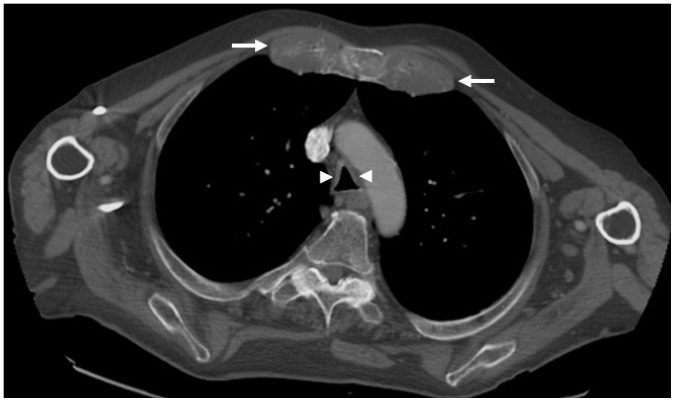

| Fig. 22Sternal dehiscence.72-year-old male with chronic sternal dehiscence following remote median sternotomy for aorto-coronary bypass surgery.

A. Chest radiograph shows fractures and misalignment of many sternal wires (arrows). B. Chest CT with coronal reformation shows separation of sternotomy edges (arrowheads).

|

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download