INTRODUCTION

The impact of air pollution on health has been a global issue for decades.

1 However, it remains an emerging problem in several regions, including Asia. Particulate matter (PM), which is a common measure of air pollution, is a complex mixture of solid and liquid particles suspended in the atmosphere. It is categorized by its aerodynamic diameter, such as PM

10 (≤10 µm) and PM

2.5 (≤2.5 µm). The former is mainly produced by construction activities and re-suspension of road dust and wind, while the latter arises mainly from combustion processes. The composition of PM may vary depending on the area where PM is generated, the season, and weather conditions.

2 According to recent statistics from the World Health Organization, the mean annual concentration of PM

2.5 is still very high and even continues to increase in Asian countries, like China, India, and Korea.

3

The range of health effects of PM is broad, but are predominantly to the cardiovascular and respiratory systems.

4 All populations can be affected, but patients with chronic respiratory disease, such as asthma, are considered to be more vulnerable to the harmful health effects of PM. Many epidemiologic studies have shown the association between air pollution and risks of asthma exacerbations and hospitalizations.

56789 The effects of PM may vary with local environment (environmental standards for PM, the compositions of PM, and medical systems) or population characteristics. Therefore, the health impact assessment performed in each country has its own significance. In addition, to our knowledge, few studies have investigated the effects of PM on overall asthma-related hospital visits, including outpatient visits. The majority of available studies have measured asthma-related emergency room visits or hospitalization only, which is a marker for severe asthma exacerbations: the severe outcomes reflect only a small portion of asthma deterioration, and the number of outpatient visits may better reflect changes in asthma activities, including mild asthma attacks. Furthermore, the effects of short-term exposure so far have only been assessed using daily average concentrations of PM, and few have examined the effects of shorter exposure (e.g., 1 or 2-hours). Interestingly, a recent study suggested the possibility that hourly increases in air pollution may increase the risk of asthma exacerbation.

10

Because the medical system of Korea is based on the National Health Insurance (NHI) system, the NHI database includes data on all nationwide outpatient visits, emergency room visits, and hospital admissions, providing an opportunity to examine the association between PM exposure and asthma-related hospital visits as a whole. Korea has been monitoring and managing PM10 and PM2.5 from 2001 and 2015, respectively. However, the number of days exceeding the daily average environmental standard has been increasing in recent years, especially in the winter and spring seasons. Previous studies have defined asthma-related hospital visits based on only the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision codes (ICD-10 codes) for asthma (J45-46). Therefore, further studies based on definitions reflecting asthma-related visits well are necessary.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of short-term exposure to PM exceeding the daily average environmental standards of Korea on asthma exacerbations based on recent NHI data with a more reliable definition of asthma-related hospital visits. We also investigated the effects of very short-term PM exposures (PM exposure exceeding the daily average environmental standards for 2 hours) on asthma-related hospital visits.

DISCUSSION

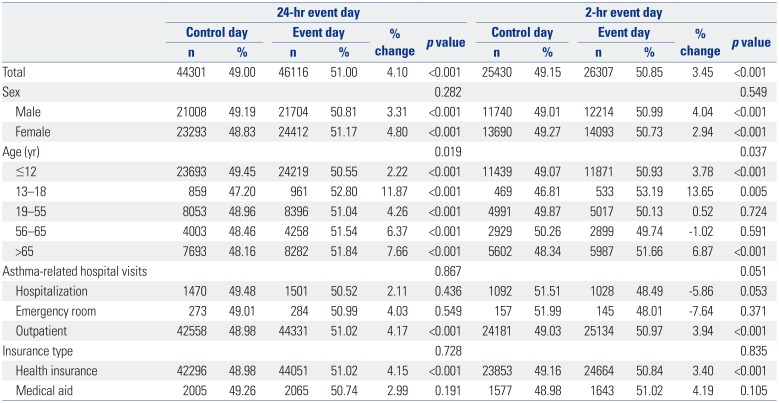

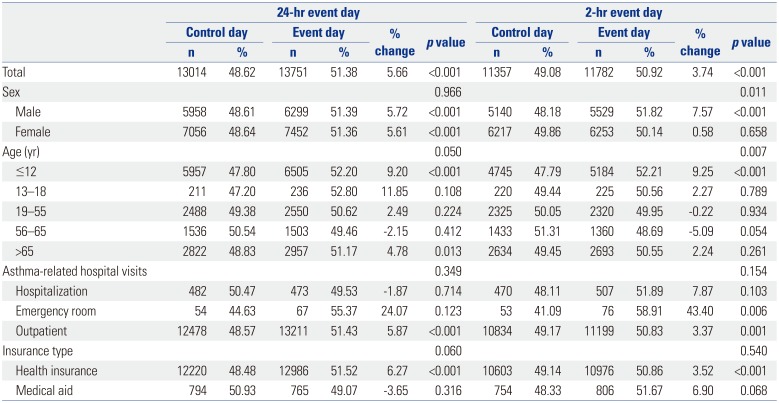

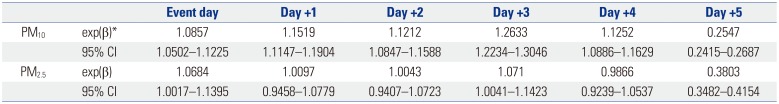

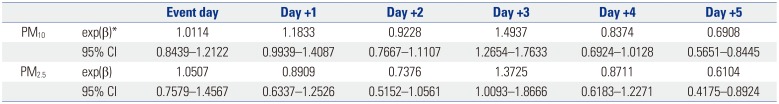

In this study, we found that the average number of asthma-related hospital visits increased on the day exceeding the daily average environmental standard for PM (PM10 ≥100 µg/m3 or PM2.5 ≥50 µg/m3). This increase was observed even on the days exceeding the environmental standard for just 2 hours. The average number of asthma-related hospital visits peaked on the third day after the event. Asthma-related hospitalizations also increased on the third day after the event. Children and older adults were found to be particularly vulnerable to the effects of PM exposure.

Although PM exposure and its associated respiratory health hazards are common concerns for everyone, vulnerable populations, such as individuals with chronic respiratory illnesses, are particularly at an increased risk. Asthma is a common chronic airway inflammatory disease affecting 1–18% of the population in different countries.

11 Although there have been a number of studies on the effects of short-term PM exposure on asthma exacerbations, the extent of the effects varies depending on the distribution of susceptible or vulnerable populations, the composition of PM, and the environmental standards and policies of each country.

Most previous studies used concentration-response functions (CRFs; the percent change in a given health outcome per µg/m

3 change in concentrations) to assess risk; however, to assess the effect of short-term exposure to PM exceeding the current environmental standard on asthma exacerbations, we investigated the average number of asthma-related hospital visits from the day exceeding the daily average environmental standard for PM

10 and PM

2.5 to 5 days after the event day. The daily average environmental standards of Korea are ≤100 µg/m

3 for PM

10 and ≤50 µg/m

3 for PM

2.5, which are higher than the WHO Air Quality Guidelines.

12 However, there is no evidence for which level of exposure is safe.

12 In this study, the average number of asthma-related hospital visits on the days exceeding the daily average environmental standard for PM

10 and PM

2.5 increased by 4.10% and 5.66%, respectively. In addition, while outpatient visits primarily increased, emergency room visits also increased on the 2-hr event days for PM

2.5. This suggests that PM

2.5 has a greater impact on asthma exacerbations than PM

10 and is associated with more severe asthma exacerbations. In a recent meta-analysis of case-crossover studies, PM

10 was also not associated with increased emergency room visits or hospitalizations, whereas PM

2.5 was.

8 However, this meta-analysis did not evaluate outpatient visits because most included studies were conducted in North America and Europe where outpatient visits are generally scheduled by appointment, leading most patients with asthma exacerbations to primarily use the emergency room. Therefore, these studies do not reliably reflect the true morbidity and offer an opportunity to examine the association between short-term PM exposure and overall asthma-related hospital visits. Among the studies that did include outpatient visits, a population-based study in Taiwan also showed that as PM

10 concentration increased, outpatient visits due to asthma increased, whereas the risk for emergency room visits and hospitalizations did not increase.

13 However, another recent study in China showed that every 10 µg/m

3 increase in PM

2.5 concentration was significantly associated with an increase in outpatient visits and emergency room visits on the same day.

14 It is not yet clear whether the reason for the difference between these studies is due to the size of PM. In addition to PM size, the difference in the severity of the asthma patients included and the medical system, including medical insurance, in each country may also be associated.

In this study, we noted a slight difference in asthma-related hospital visits after PM exposure among regions (

Supplementary Tables 1,

2,

3,

4,

5, online only). We assume that various factors, including the composition of PM, the severity of asthma, and socioeconomic factors, are involved. Further research is needed to clarify this.

In this study, we noted a time lag (measured in days) between short-term PM exposure and asthma exacerbations. Asthma-related hospital visits increased beginning the day when PM

10 or PM

2.5 exceeded the daily average environmental standard, peaked on the third day after the event, and then decreased. Hospitalizations that could be considered as a moderate to severe deterioration of asthma also increased on the third day after the event. Previous studies have also described a time lag of 0–4 days, suggesting that PM is not simply acting as an airway irritant.

715 In experimental studies using animal models and in vitro airway epithelial cells, a cause-and-effect relationship between ambient PM

10 and asthma exacerbation was demonstrated via oxidative stress, with release of interleukin-33.

1617 In addition, human airway epithelial cells exposed to PM expressed inflammatory cytokines.

18 Although the mechanism by which PM induces asthma exacerbation is not well known, these results suggest that PM can cause asthma symptoms through induction and aggravation of airway inflammation. The time lag from PM exposure to hospital visits can also be partially explained by these results.

One reason for various time lags in individual studies may be variations in asthma severity in the study population. If a study includes a large number of patients with moderate to severe asthma, the time lag may be shorter than in studies including predominantly mild patients. However, most studies, including this study, did not include the asthma severity of their study population in the analysis due to limitations in the data used. Another reason may be the difference in composition of PM. The composition of PMs varies depending on the primary emission source and the weather conditions in each country or region.

219 Several studies reported that the health effects of PM are different depending on their composition.

20 However, which constituents of PM have a major influence on the deterioration of asthma remains to be elucidated, and this should be clarified in order to correctly understand and reduce the health effects of PM.

What is interesting to note in this study is that even after exposure to PM

10 or PM

2.5 exceeding the environmental standard for a very short period of time, the number of asthma-related hospital visits increased. Although they increased less than on the day exceeding the daily average environmental standard, asthma-related hospital visits significantly increased even on the day exceeding the environmental standard for only 2 hours. Although the short time lag (1–6 hours) from PM

10-2.5 exposure to asthma-related emergency department visits in a recent study suggested the possibility that asthma exacerbation could occur even after exposure to an hourly increase in PM

10, this is the first study to confirm the effects of exposure to increased PM over several hours on asthma-related hospital visits. Unlike hourly average environmental standards for other air pollutants, there are no countries that set hourly average environmental standards for PM, except Japan.

21 Although it will need to be verified by other studies, the results of this study suggest that it may be necessary to establish hourly average environmental standards for PM just as for other air pollutants.

In the present study, the effect of PM

2.5 on asthma-related hospital visits on the event day was more prominent than that of PM

10, although thereafter, the effect was less than that of PM

10. This is in contrast to a recent study from Hong Kong that reported a more delayed observable response after PM

2.5 exposure.

21 One reason for this discrepancy may be a difference in the composition of PM as described above. Therefore, it is necessary to establish a nationwide monitoring network by increasing the number of monitoring stations and evaluate the composition of PM in parallel.

Many recent studies have focused on the association between PM

2.5 exposure and asthma exacerbation based on results indicating that the influence of PM

2.5 is greater than that of PM

10, thus neglecting the effects of PM

2.5-10, which is included in PM

10. However, an experimental study demonstrated that PM

10 causes more damage to airway epithelial cells than PM

2.5, which is explained by the ionic component contained in PM

10.

22 These findings suggest that studies or policies on the assessment of health effects of PM should not be limited to PM

2.5.

In this study, the effects of PM exposure on asthma exacerbations were more pronounced in children and older adults, which is consistent with previous findings.

2324 However, the effect on adolescents was significantly higher when compared to other studies. This seems to be due to the fact that in this population, compliance with parental and school instructions, such as reduction of outdoor activities and mask use on days of high ambient PM concentrations, is low compared to younger children.

Asthma-related hospital visits on the event day varied according to insurance type in this study. Although the government pays medical expenses for patients covered by medical aid in Korea, asthma-related hospital visits on the event day did not increase in the medical aid group, unlike the health insurance group. This is likely due to differences in health behavior and use of medical institutions among different socioeconomic groups, rather than differences in the effect of PM on asthma exacerbation depending on insurance type.

25

This study has several strengths. First, this is a nationwide study that evaluated the short-term effects of PM on asthmatic patients, including outpatient visits, as well as emergency room visits and hospitalizations, based on the latest NHI data. Second, in order to increase the reliability of actual hospital visits due to asthma, a working definition, which included the prescription of asthma medication along with the ICD-10 codes, was applied. Finally, we assessed the effect of very short-term PM exposure (2 hours) on asthma exacerbation for the first time.

Several potential limitations of this study should be taken into consideration. First, among the outpatient visits due to asthma, we could not exclude patients who visited clinics for regular follow up. However, given that the event day and the control day were the same day of the week at a 7 day interval, the number of patients visiting clinics for regular follow up could be estimated to be similar, so their possible effect may be negligible. Although seasons or viral epidemics can affect asthma exacerbations, for the same reason, we think their effects were also negligible. Second, PM

2.5 data were collected from a relatively small number of monitoring stations, compared to PM

10, which can cause an exposure measurement error and underestimate the effects of PM

2.5.

26 In addition, since the composition of PM is not yet monitored in Korea, the influence of PM composition cannot be analyzed. Third, because of the limited data available, the impact of other air pollutants, such as sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide, and ozone, could not be appropriately adjusted for. Although the levels of sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide on the event days were slightly higher than that on control days, their possible effect would not be significant since the levels were far below the current daily average environmental standard (see

supplementary materials for details). However, additional studies are warranted to examine the independent effect of PM on asthma.

In conclusion, we found a significant association between short-term PM exposure exceeding the current daily average environmental standard and asthma-related hospital visits. This association was also observed even after PM exposure exceeded the current environmental standard for just 2 hours. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the impact of PM exposure on asthmatic patients based on the daily average environmental standard. Although further studies investigating the actual harmful constituents of particulates and time course of PM induced effects are needed to better understand the effects of PM exposure on asthma, these results are expected to contribute to the establishment of appropriate environmental standards and relevant policies for PM. In addition to implementing effective policies to reduce ambient PM levels, accurate forecasts based on a nationwide monitoring network and continuous publicity and education are important for preventing and minimizing the harmful effects of PM on asthma exacerbation.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download