Abstract

Objectives

This study compared the demographic and clinical characteristics of police referrals with referrals from other sources to a psychiatric emergency department.

Methods

A retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted on the data from the psychiatric emergency department of Ulsan University Hospital from January 2014 to October 2017. The study sample consisted of 79 psychiatric patients who were referred by police, and the characteristics of this group were compared with those of 240 psychiatric patients who were referred by other sources. The collected data were analyzed using a chi-square, Fisher's exact test, and independent sample t-tests.

Results

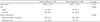

Among the 1768 psychiatric emergency visits, 89 (5.0%) were referred by police, and among the 79 referrals by police chosen as the study group, there were 4(5.1%) cases of emergent psychiatric admission. These patients referred by police were more likely to be male and in a lower socio-economic status. Police referrals were more likely to exhibit violent behavior, be restrained, and more likely to visit after working hours. They were notified more rapidly to the psychiatric department, less notified to other departments, and visited the psychiatric outpatient clinics less after discharge from the emergency department.

Conclusion

The study results highlight the importance of understanding the characteristics of psychiatric emergency patients referred by police and identifying the problems of the current psychiatric emergency services. Systems need to be developed that clarify the roles of police in psychiatric emergencies and facilitate collaboration between police and mental health institutions.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Steadman HJ, Morrissey JP, Braff J, Monahan J. Psychiatric evaluations of police referrals in a general hospital emergency room. Int J Law Psychiatry. 1986; 8:39–47.

2. Way BB, Evans ME, Banks SM. An analysis of police referrals to 10 psychiatric emergency room. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1993; 21:389–397.

4. Maharaj R, Gillies D, Andrew S, O'Brien L. Characteristics of patients referred by police to a psychiatric hospital. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011; 18:205–212.

5. Fry AJ, O'Riordan DP, Geanellos R. Social control agents or front-line carers for people with mental health problems: police and mental health services in Sydney, Australia. Health Soc Care Community. 2002; 10:277–286.

6. Sellers CL, Sullivan CJ, Veysey BM, Shane JM. Responding to persons with mental illnesses: police perspectives on specialized and traditional practices. Behav Sci Law. 2005; 23:647–657.

7. Ministry of Health and Welfare, National Center for Mental Health. Act on the improvement of mental health and the support for welfare services for mental patients, article 50(1-2). Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2019.

8. Korean National Police Agency. Act on the performance of duties by police officers, article 4(1). Seoul: Korean National Police Agency;2018.

9. Kimhi R, Barak Y, Gutman J, Melamed Y, Zohar M, Barak I. Police attitudes toward mental illness and psychiatric patients in Israel. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1998; 26:625–630.

10. Evans ME, Boothroyd RA. A comparison of youth referred to psychiatric emergency services: police versus other sources. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2002; 30:74–80.

11. Redondo RM, Currier GW. Characteristics of patients referred by police to a psychiatric emergency service. Psychiatr Serv. 2003; 54:804–806.

12. Lee S, Brunero S, Fairbrother G, Cowan D. Profiling police presentations of mental health consumers to an emergency department. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2008; 17:311–316.

13. Meadows G, Calder G, Van den Bos H. Police referrals to a psychiatric hospital: indicators for referral and psychiatric outcome. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1994; 28:259–268.

14. Dhossche DM, Ghani SO. Who brings patients to the psychiatric emergency room? Psychosocial and psychiatric correlates. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1998; 20:235–240.

15. Wang JP, Wu CY, Chiu CC, Yang TH, Liu TH, Chou P. Police referrals at the psychiatric emergency service in Taiwan. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2015; 7:436–444.

16. Welfarenews.net [homepage on the Internet]. Seoul: Welfarenews;updated 2017 Mar 16. cited 2019 Apr 23. Available from: http://www.welfarenews.net/news/articleView.html?idxno=60690.

17. Ncmh.go.kr [homepage on the Internet]. Seoul: National Center for Mental Health;updated 2018 Dec 6. cited 2019 Apr 20. Available from: http://www.ncmh.go.kr/kor/data/snmhDataView2.jsp?no=8392&fno=106&menu_cd=K_04_09_00_00_S0.

18. Law.go.kr [homepage on the Internet]. Sejong: National Law Information Center;updated 2001 Feb 23. cited 2019 Apr 23. Available from: http://www.law.go.kr/precInfoP.do?mode=0&precSeq=191241.

19. Hani.co.kr [homepage on the Internet]. Seoul: Hankyoreh;updated 2019 Jan 1. cited 2019 Apr 23. Available from: http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/society/society_general/876569.html.

20. Newspim.com [homepage on the Internet]. Seoul: Newspim;updated 2019 Apr 21. cited 2019 Apr 25. Available from: http://www.newspim.com/news/view/20190421000095.

21. Burley M, Morris M. Involuntary civil commitments: common questions and a review of state practices. Olympia: Washington State Institute for Public Policy;2015.

22. Parliament of the United Kingdom. Mental Health Act 1983, section 4. London: Parliament of the United Kingdom;1983.

23. Ncmh.go.kr [homepage on the Internet]. Sejong: National Center for Mental Health;updated 2018 Feb 14. cited 2019 Apr 20. Available from: http://www.ncmh.go.kr/kor/data/snmhDataView2.jsp?no=8300&fno=106&menu_cd=K_04_09_00_00_S0.

24. Ncmh.go.kr [homepage on the Internet]. Seoul: National Center for Mental Health;cited 2019 Apr 20. Available from: http://www.ncmh.go.kr/kor/dep/depReportView.jsp?no=638&fno=84&depart=0&search_gubun=1&pg=1&search_item=1&search_content=%C0%CE%B1%C7%C1%F5%C1%F8&menu_cd=K_04_10_00_00_T0&category=.

25. Sisa21.kr [homepage on the Internet]. Suncheon: Sisa 21;updated 2018 Aug 29. cited 2019 Apr 20. Available from: http://www.sisa21.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=10900.

26. Hansen AH, Høye A. Gender differences in the use of psychiatric outpatient specialist services in Tromsø, Norway are dependent on age: a population-based cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015; 15:477.

27. Staniloiu A, Markowitsch H. Gender differences in violence and aggression – a neurobiological perspective. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2012; 33:1032–1036.

28. Denning DG, Conwell Y, King D, Cox C. Method choice, intent, and gender in completed suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2000; 30:282–288.

29. Greitemeyer T, Sagioglou C. Subjective socioeconomic status causes aggression: a test of the theory of social deprivation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2016; 111:178–194.

30. Kleinman JC, Gold M, Makuc D. Use of ambulatory medical care by the poor: another look at equity. Med Care. 1981; 19:1011–1029.

31. Aday LA, Andersen RM. The national profile of access to medical care: where do we stand? Am J Public Health. 1984; 74:1331–1339.

32. Nicks BA, Manthey DM. The impact of psychiatric patient boarding in emergency departments. Emerg Med Int. 2012; 2012:360308.

33. Alakeson V, Pande N, Ludwig M. A plan to reduce emergency room ‘boarding’ of psychiatric patients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010; 29:1637–1642.

34. Lamb HR, Shaner R, Elliott DM, DeCuir WJ Jr, Foltz JT. Outcome for psychiatric emergency patients seen by an outreach police-mental health team. Psychiatr Serv. 1995; 46:1267–1271.

35. Pinfold V, Huxley P, Thornicroft G, Farmer P, Toulmin H, Graham T. Reducing psychiatric stigma and discrimination--evaluating an educational intervention with the police force in England. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003; 38:337–344.

36. Broussard B, McGriff JA, Demir Neubert BN, D'Orio B, Compton MT. Characteristics of patients referred to psychiatric emergency services by crisis intervention team police officers. Community Ment Health J. 2010; 46:579–584.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download