I. Introduction

Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) is one of the most common acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-defining neoplasms, accounting for one-third of AIDS-related malignancies

12. Burkitt's lymphoma (BL) is an uncommon highly aggressive B-cell NHL, first described by Dr. Dennis Burkitt in 1958

34. BL has the highest proliferation rate of any human neoplasm, with a possible doubling time of 24 hours

3. Three forms of BL have been described by World Health Organization (WHO): 1) Endemic, 2) sporadic, and 3) immunodeficiency-associated

4. BL exhibits an elevated incidence in immunocompromised patients, especially those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, accounting for 2.4% to 20% of HIV-associated NHLs

23. Extra nodal sites particularly in the abdomen and lymph node are the most common sites for HIV-associated BL, and intraoral lesions are very uncommon

56. This subtype is considered one of the primary/initial conditions indicating an underlying HIV infection

6. Therefore, we report a case of HIV-associated BL presenting as an intraoral mass in a female Indian patient.

II. Case Report

A 30-year-old female reported to our institution with a chief complaint of an asymptomatic, gradually enlarging growth in the lower left back region of the jaw for 4 months. The patient did not reveal any significant medical history or drug allergies. Extraoral examination revealed facial asymmetry caused by a soft, painless swelling of the left cheek. An enlarged left submandibular lymph node was noted. Intraoral examination showed a solitary, well-defined, sessile, exophytic mass covered by slough, extending anteroposteriorly and buccolingually from the 35th to 38th region.(

Fig. 1) The lesion was non-tender, soft in consistency, and measured approximately 3 cm×4 cm in diameter. Panoramic radiograph showed superficial bone loss in the area of the lesion, with no evidence of intraosseous extension. Considering these features, a provisional diagnosis of malignant tumor was suspected. Gingival enlargement, periodontal disease, fungal infection, granulomatous diseases like Wegener's granulomatosis, epithelial malignancies such as squamous cell carcinoma, connective tissue tumors like fibromatosis and fibrosarcoma, and lymphoproliferative disorders like lymphoma and leukemia were also considered in the differential diagnosis. Since these lesions are clinically indistinguishable, a histopathologic examination in the form of an incisional biopsy was performed, and the excised tissue was subjected to histopathologic evaluation to obtain a confirmatory diagnosis.

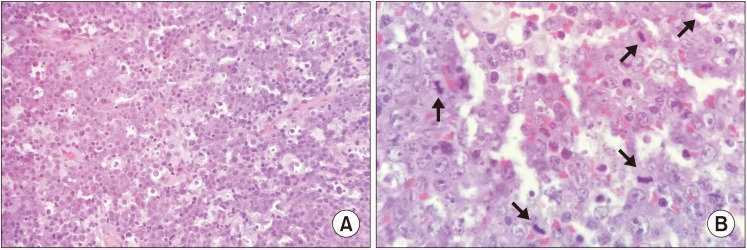

Microscopic examination revealed diffuse proliferation of uniformly sized neoplastic lymphoid cells. The cells showed hyperchromatic round nuclei with multiple nucleoli and basophilic cytoplasm. Numerous tingible body macrophages with clear cytoplasm were seen interspersed among the tumor cells, producing a starry sky appearance.(

Fig. 2. A) The cells also demonstrated pleomorphism and increased abnormal mitotic figures.(

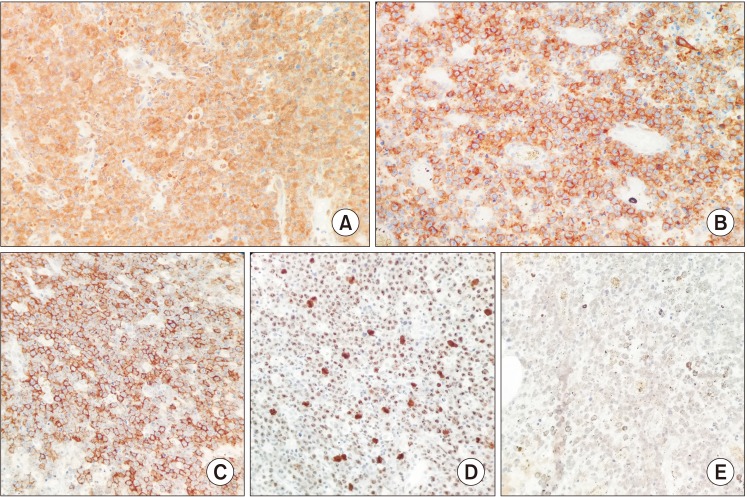

Fig. 2. B) Immunohistochemical analysis showed that the tumor cells were positive for c-myc, CD10, CD20, and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) (

Fig. 3. A–C, 3. E) and negative for CD3, Bcl2, Bcl6, and MUM1. The Ki-67 proliferative index was nearly 100%.(

Fig. 3. D) Based on the histologic and immunohistochemical findings, the diagnosis was BL. Since this particular intraoral location of BL is uncommon in non-endemic regions, it was suspected that the patient might be immunocompromised. Therefore, the patient was asked to undergo serological testing for HIV, which turned out to be positive, resulting in a final diagnosis of HIV-associated BL. Unfortunately, further investigations could not be performed as the patient was lost to follow-up.

III. Discussion

Patients with HIV infection are at high risk of developing malignancies. NHL constitutes the second most common variety of these neoplasms and is considered an AIDS-defining entity

1. The most common types of NHLs seen in HIV/AIDS patients include diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and BL, accounting for 7% to 20% of cases

789. Abdominal, nodal, and bone marrow involvement are frequent for HIV-associated BL, and Central Nervous System (CNS) involvement is seen in 13% to 17% of cases

46. Intraoral locations are a relatively rare occurence

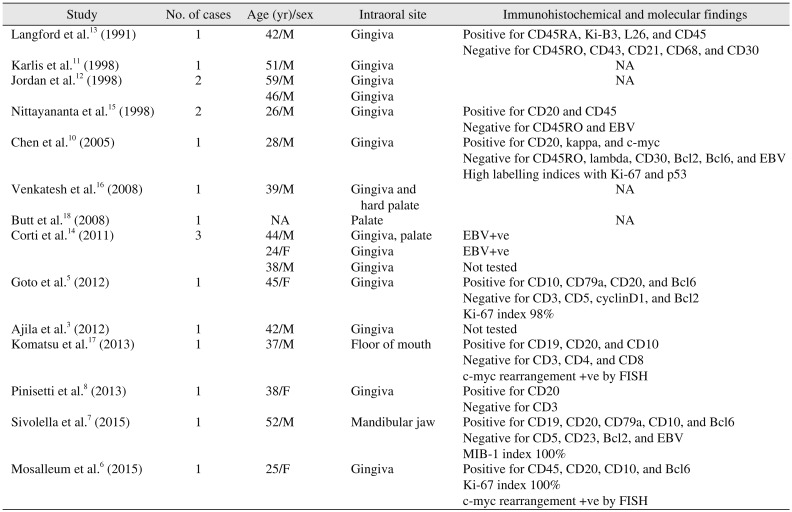

10. A summary of literature reporting intraoral HIV-associated BL is depicted in

Table 1.

Literature strongly suggests EBV infection and dysregulation of the c-myc (c-myelocytomatosis) oncogene as possible causes of BL

7. Approximately 98% of endemic BL, 20% of sporadic BL, and 30% to 40% of immunodeficient BL exhibit an association with EBV

2. EBV promotes B-cell hyperplasia, an essential step in lymphomagenesis. This increases the risk of chromosomal rearrangement associated with c-myc oncogene expression. The c-myc immunoglobulin (Ig) translocation is thought to arise as a result of errors in activation-induced cytidine deaminase-mediated Ig class switch recombination in germinal centers, leading to proliferation of neoplastic cells

3678. In addition, when HIV infection is associated with BL, it causes uncontrolled polyclonal activation of B cells

8.

Approximately 4% of NHLs associated with HIV occur in the oral cavity

5. The data available regarding intraoral HIV-associated BL indicate the gingiva as the most frequently affected site and primary occurrence in males

3567810111213141516. Lesions on the palate, floor of the mouth, and lower jaw have also been reported

1718. The most frequently affected ages were from the 3rd to 5th decades. A lesion usually presents as a rapidly growing ulcerative mass with a necrotic surface

25810. Intraoral and extraoral swelling along with tooth loosening and mobility are seen with jaw lesions

37. Radiographic findings include ill-defined radiolucency with loss of trabecular pattern of the mandible or maxilla

3. The present case involved an exophytic growth with surface ulceration in the mandibular gingiva in a 30-year-old female patient. Clinically, BL may mimic a variety of orofacial pathologies; hence, clinical differential diagnosis should include periodontal disease, deep fungal infection, granulomatous diseases, and malignant neoplasms

15.

Microscopically, HIV-associated BL exhibits features of classic BL. These include diffuse monotonous proliferation of sheets of small to intermediate-sized malignant cells that exhibit moderately abundant basophilic cytoplasm with round, regular nuclei containing multiple nucleoli

12 and abundant mitotic figures. Numerous scattered tangible body macrophages with clear cytoplasm (as a result of phagocytosis of apoptotic cells) form a starry-sky appearance

15. Previously, the WHO had suggested three histological subtypes of HIV-associated BL: classic BL, BL with plasmacytoid differentiation, and atypical BL. However, these subtypes are no longer favored, and the variants have been described as a separate entity of B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable with features intermediate between DLBCL and BL

14.

Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells of BL show positivity for Pan B-cell antigens that include CD19, CD20, CD22, and CD79a; may co-express CD10, BCl-6, CD43, and p53; and show immunonegativity for MUM-1,CD5, CD23, BCL-2, CD138, and TdT (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase)

27819. This immunoprofile suggests a follicle center origin of BL. The tumor cells have a high proliferation rate, as shown with the nearly 100% nuclear reactivity of Ki-67

20. In addition, chromosomal rearrangement of MYC is most common in the form of translocation of t(8;14) detected by fluorescent

in situ hybridization (FISH)

1. The present case also showed immunoreactivity for CD10, CD20, c-myc, and EBV and immunonegativity for CD3, BCL2, BCL6, and MUM-1.

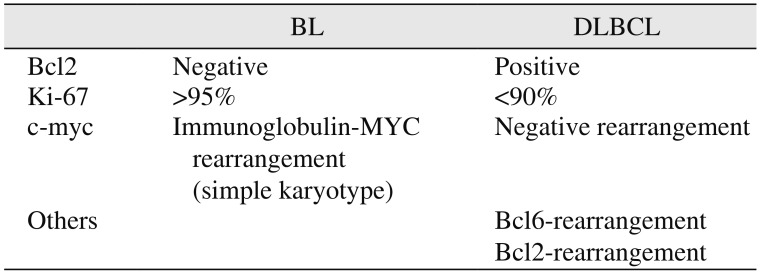

Features like the starry sky pattern, BL-like immunophenotype, and high proliferation fraction in some DLBCLs necessitates that BL be distinguished from DLBCL, as the two entities require different treatment modalities

19. DLBCL is traditionally treated by CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) therapy with the anti-B cell antibody rituximab, whereas adult BL frequently requires a high intensity chemotherapy regimen including CNS prophylaxis to improve overall survival

1920. The WHO recommends positivity for CD10, BCL6, and Ki-67 >90%; negativity for BCL2 with the presence of a MYC breakpoint; and absence of BCL2 and/or BCL6 breakpoints for diagnosis of BL

20. Therefore, researchers have reached a consensus regarding the practical approach for this differentiation and have suggested that positivity for CD10, BCL6, and Ki-67 >90%; negativity for BCL2; presence of an MYC breakpoint; and absence of BCL2 and/or BCL6 breakpoints favor diagnosis of BL

1920. The differences between BL and DLBCL are depicted in

Table 2. Our case showed positivity for CD10 (germinal center-associated marker

17), CD20 (mature B cell with monotypic surface antigens

6), c-myc, and EBV and negativity for CD3 (T-cell associated marker

17), Bcl6, Bcl2 (marker for activated B-cell), and MUM1 (plasma cell marker

14). Based on these findings, we confirmed the diagnosis of BL. Therefore, the final diagnosis of BL should be established with the help of immunohistochemistry and molecular investigations.

The primary mode of treatment for BL is intensive multiagent chemotherapy. In HIV patients, modified protocols are used to reduce toxicity

6. However, HIV-associated BL is less sensitive to chemotherapy compared to endemic forms and shows poor prognosis with a tendency to relapse

58. In cases of extra nodal HIV-associated BL, thorough investigations should be performed to detect other sites of involvement, and patients should be treated accordingly.

In conclusion, the present case and analysis of previously reported cases suggest that intraoral BL can be the initial manifestation of HIV infection in patients. Therefore, such an oral presentation should raise the suspicion of an underlying immunocompromised state. BL should be differentiated from DLBCL, as they require different treatments. As a result, detailed knowledge on the etiopathogenesis, clinical presentation, and histopathology along with immunological and molecular profiles is critical to obtain a final diagnosis.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download