Abstract

Lung cysts are commonly seen on computed tomography (CT), and cystic lung diseases show a wide disease spectrum. Thus, correct diagnosis of cystic lung diseases is a challenge for radiologists. As the first diagnostic step, cysts should be distinguished from cavities, bullae, pneumatocele, emphysema, honeycombing, and cystic bronchiectasis. Second, cysts can be categorized as single/localized versus multiple/diffuse. Solitary/localized cysts include incidental cysts and congenital cystic diseases. Multiple/diffuse cysts can be further categorized according to the presence or absence of associated radiologic findings. Multiple/diffuse cysts without associated findings include lymphangioleiomyomatosis and Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Multiple/diffuse cysts may be associated with ground-glass opacity or small nodules. Multiple/diffuse cysts with nodules include Langerhans cell histiocytosis, cystic metastasis, and amyloidosis. Multiple/diffuse cysts with ground-glass opacity include pneumocystis pneumonia, desquamative interstitial pneumonia, and lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia. This stepwise radiologic diagnostic approach can be helpful in reaching a correct diagnosis for various cystic lung diseases.

Many diseases or conditions are associated with air-filled lung lesions, which are increasingly being encountered in chest computed tomography (CT) because of the widespread use of CT scans in daily clinical practice. Lung cysts appear as round parenchymal lucencies or low-attenuating areas with a well-defined thin wall surrounded by normal lung parenchyma (1). Cysts in other body parts are usually indicative of fluid-containing lesions, while cysts in the lung usually contain air, but occasionally contain fluid or solid material (1). Radiologically, air-filled lung cysts are simply called air cysts or cysts. In this review, we mainly focus on air-filled lung cysts identified on chest CT.

Diseases or conditions presenting with lung cysts occupy a broad spectrum, and cystic lung diseases are a heterogeneous group of pathologies for which differential diagnosis can be complicated. For radiologic assessment of cystic lung diseases, it is important to differentiate true lung cysts from other air-filled lung lesions in the first step of the diagnostic process. Radiologic characteristics of lung cysts, including size, wall thickness, number, location, and distribution, and the associated radiologic findings provide the most helpful diagnostic clues for diagnosing specific cystic lung diseases. A definite diagnosis may require clinical correlation and, occasionally, biopsy. However, although a multidisciplinary approach is necessary to make the correct diagnosis, a radiologic approach is particularly important in narrowing the differential diagnosis.

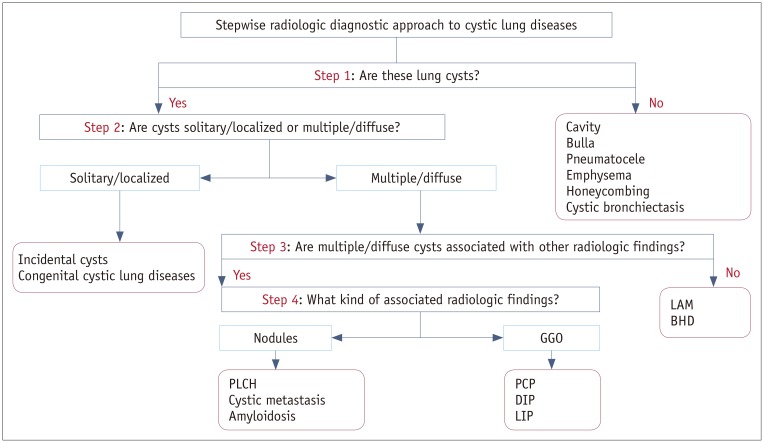

The purpose of this review is to provide a stepwise radiologic diagnostic approach for cystic lung diseases (Fig. 1).

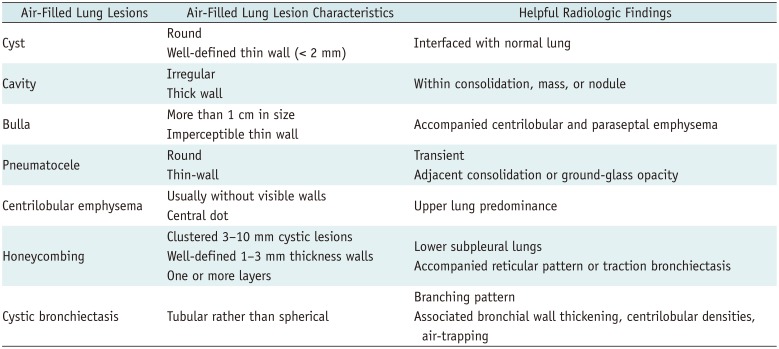

Radiologically, air-filled lung lesions have overlapping features and their names are sometimes used interchangeably. However, a radiologic distinction between cysts and cyst-like lesions is the first step in the radiologic approach to correct diagnosis, although some overlap may exist (Table 1).

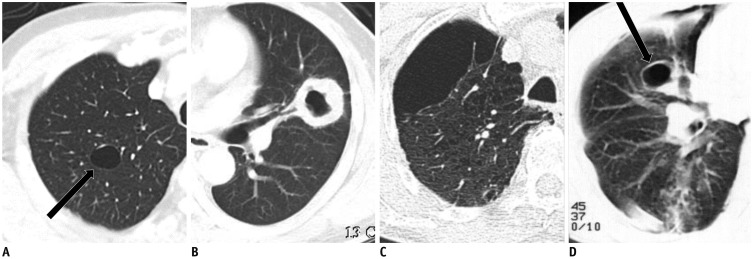

A cyst appears as a round parenchymal lucency or lowattenuating area with a well-defined interface with normal lung parenchyma. Cysts have variable wall thickness but are usually thin-walled (< 2 mm) and occur without associated pulmonary emphysema on CT scans (Figs. 2A, 3A) (1). Pathologically, a cyst is any round circumscribed space that is surrounded by an epithelial or fibrous wall of variable thickness (1). The pathogenesis of lung cyst formation is not well understood for any of the cystic lung diseases. Lung cysts can be caused by various mechanisms, including check valve airway obstruction with distal airspace dilatation, ischemia and necrosis of the airway walls, and lung parenchymal destruction by proteases (2).

Lung cysts are often confused with other air-filled lesions in the lung parenchyma, because they may not be surrounded by a wall or they may have very thin or thick walls; they are not interfaced with normal lung parenchyma; and they are often found in unusual locations. Therefore, single or several cysts in a localized area of the lung should be distinguished from a cavity, pneumatocele, or bullae. Moreover, multiple cysts diffusely distributed in both lungs should be distinguished from emphysema, honeycombing, and cystic bronchiectasis.

A cavity is a gas-filled space that is observed as a lucency or low-attenuated area within pulmonary consolidation, a mass, or a nodule (Fig. 2B) (1). Cavity wall thickness may vary, but the wall is usually relatively thick (34). Some cavitary lesions may appear as thin-walled cavities or cysts at their end-stage presentation (5). Many different diseases present as cavitary lesions. This spectrum of diseases includes acute to chronic infections, chronic systemic diseases, and primary or metastatic malignancies (45).

A cavity is differentiated from a cyst by the presence of a thicker wall and a more irregular shape.

A bulla is an airspace measuring more than 1 cm that is sharply demarcated by a thin wall (1). Radiologically, it appears as a rounded focal lucency or decreased attenuation more than 1 cm in size, and is bounded by a thin, usually almost undetectable wall that is not greater than 1 mm (Fig. 2C). Bullae are usually located in the subpleural lung rather than within the lung parenchyma. Multiple bullae are usually accompanied by adjacent paraseptal and centrilobular emphysema (1).

Bullae can be distinguished from cysts by their almost imperceptible thin-wall, subpleural location, and accompanying adjacent emphysema.

A pneumatocele is a transient, thin-walled, gas-filled lesion, usually caused by pneumonia, trauma, or aspiration of hydrocarbon fluid (1). The mechanism underlying their formation is believed to be a combination of parenchymal necrosis and check valve airway obstruction. Radiologically, a pneumatocele appears as an almost round, thin-walled airspace in the lung (Fig. 2D) (1). Pneumatoceles can be accompanied by adjacent consolidation or ground-glass opacity as a result of recent pneumonia; they may progressively increase in size over the following days or weeks, and then resolve after weeks or months (6).

Pneumatoceles appear transiently following recent pneumonia or trauma, which is an important distinguishing feature from cysts.

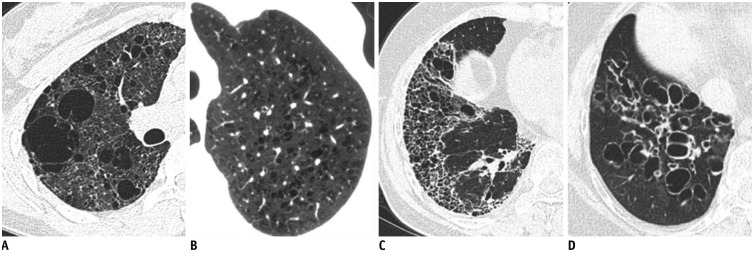

Pulmonary emphysema can be classified into three major subtypes based on disease distribution within secondary pulmonary lobules: centrilobular or centriacinar emphysema, panlobular or panacinar emphysema, and paraseptal or distal acinar emphysema (178). Centrilobular emphysema is the most common type of pulmonary emphysema, and is pathologically defined by the presence of destroyed centrilobular alveolar walls and enlarged respiratory bronchioles and associated alveoli (1). Centrilobular emphysema typically appears in focal areas of decreased lung attenuation, usually without visible walls, and it has a predilection for the upper lungs (189). Centrilobular emphysema is usually combined with a central dot which is a central bronchovascular bundle in the secondary pulmonary lobule (Fig. 3B). However, centrilobular emphysema may appear similar to thin-walled cysts. Paraseptal emphysema involves the more distal part of the secondary pulmonary lobule, and usually presents as a single row of elongated, thin-walled, air-filled structures that are distributed within the subpleural lung. Panlobular emphysema involves the destruction of the entire secondary pulmonary lobule, and it involves lung parenchyma more diffusely, especially in the lower lungs (8).

Cysts are larger, fewer in number, lack a centrilobular location, lack a central core vessel, and have more visible walls compared with centrilobular emphysema.

Honeycombing represents destroyed and fibrotic lung tissue containing numerous cystic airspaces with thick fibrous walls, indicative of the late stages of various lung diseases (1). Radiologically, it appears as clustered cystic lesions with 1–3 mm-thick well-defined walls, which are typically 3–10 mm in diameter but may be occasionally larger (Fig. 3C) (110). Honeycombing is characterized by multiple rows of air-filled spaces clustered in the subpleural region, predominantly in the lower lungs. It usually presents as multiple layers, but it can present as a single layer (10). Honeycombing usually accompanies other features of lung fibrosis, such as reticulation and traction bronchiectasis. It is the most distinguishing feature of usual interstitial pneumonia pattern, which is a hallmark radiologic pattern of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (10).

Cysts are larger in size, lack a subpleural distribution, do not show associated fibrosis, and are isolated lesions in comparison with honeycombing.

Bronchiectasis is an irreversible, localized, or diffuse bronchial dilatation, usually resulting from chronic infection, proximal airway obstruction, or congenital bronchial abnormalities (1). Bronchiectasis may be classified as cylindric, varicose, or cystic, depending on the appearance of the affected bronchi (1). Cystic bronchiectasis can also be mistaken for cysts when a dilated airway is viewed in cross-section (Fig. 3D).

Bronchiectasis is usually distinguished from true cysts by careful examination of contiguous CT images. Findings such as tubular rather than spherical dimensions, branching patterns, associated bronchial wall thickening, centrilobular densities, and air-trapping are helpful for the diagnosis of bronchiectasis.

As a second step, after differentiating cysts from cyst mimickers, lung cysts can be categorized as solitary/localized cysts or multiple/diffuse cysts. Single or several cysts in a localized area are classified as solitary/localized cysts, while multiple or numerous cysts distributed in both lungs are classified as multiple/diffuse cysts. Below, solitary/localized cysts are reviewed in detail. Multiple/diffuse cysts will be reviewed in further detail in the following steps.

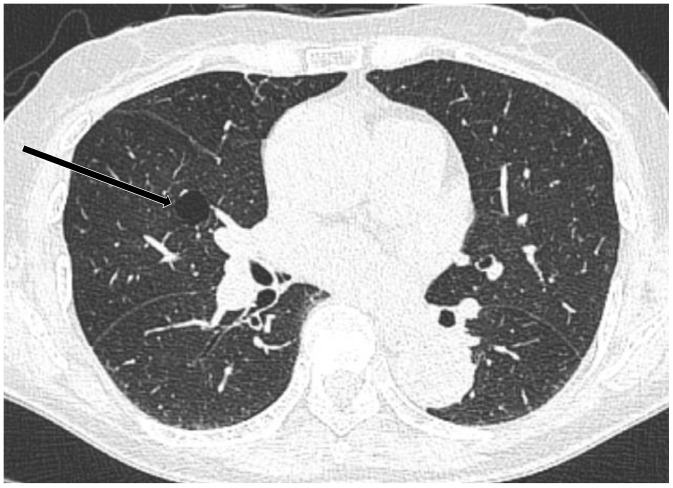

A solitary cyst or several small lung cysts can be found incidentally on CT scans (Fig. 4). One study reported that cysts were seen in 25% of subjects over 75 years of age, but were not seen in subjects under 55 years of age (11). Another study found lung cysts in 7.6% of subjects on chest CT. The prevalence of multiple lung cysts was 0.9% among all participants. Although pulmonary cysts are mostly solitary, they can occur sporadically or in multiple. Cysts are not observed in participants younger than 40 years of age, and their prevalence increases with age. Cysts are most likely to appear solitarily in the lower peripheral lungs and remain unchanged or slightly increase in size over time. Cysts are not associated with impairment in measures of spirometry, cigarette smoking, or emphysema. Therefore, incidental lung cysts could be a part of the normal aging process (12). However, a single cyst may also be a remnant of a previous infection or trauma (13).

It is important to differentiate incidental lung cysts from other cystic lung diseases. Solitary or several small thinwalled lung cysts incidentally found on CT in the old age group may be a part of the normal aging process. Thus, old age, smaller number, and a lack of association with other radiologic findings are useful for the differentiation of incidental lung cysts from cystic lung diseases.

Congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM) is a heterogeneous group of cystic and non-cystic lung lesions that result from abnormal bronchial structure proliferations (14). CPAM, formerly known as congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation, usually presents during childhood and rarely in adulthood. CPAM is classified into subtypes based on cyst size and location, as well as other associated congenital abnormalities (2). CPAM may communicate with the proximal airways, although this communication is abnormal. Most CPAMs derive their blood supply from the pulmonary artery and drain via the pulmonary veins (14).

Radiologically, large cysts, small cysts, and microcystic or solid lesions are observed according to the CPAM subtypes. Radiologic findings correlate well with the underlying histopathological characteristics (15). CT shows lesions with a solitary well-defined thin-walled cyst or multiple cysts of varying sizes with variable densities, depending on the fluid contents of the cysts (Fig. 5) (14). Air-fluid levels may also be identified. Small cysts occasionally merge with adjacent lung parenchyma (14).

The bronchogenic cyst is a developmental anomaly that results from abnormal budding or a branching defect between the 26th and 40th gestation days (141617). Although a bronchogenic cyst usually presents as a middle mediastinal mass along the tracheobronchial tree, it can also present as a lung mass in about one-third of the cases, with a predilection in the lower lobes (1317). Intrapulmonary bronchogenic cysts are usually filled with fluid, and air-filled intrapulmonary bronchogenic cysts are rare (13).

Radiologically, an intrapulmonary bronchogenic cyst appears as a well-defined, homogeneous, spherical lesion with a smooth or lobulated margin on CT. Cysts contain usually fluid and rarely air with or without air-fluid level (Fig. 6) (1317). Air-filled intrapulmonary bronchogenic cysts are sometimes difficult to differentiate from lung abscess or infected bullae. Clinical manifestations and previous chest radiographs and CT scans may be helpful for differentiation.

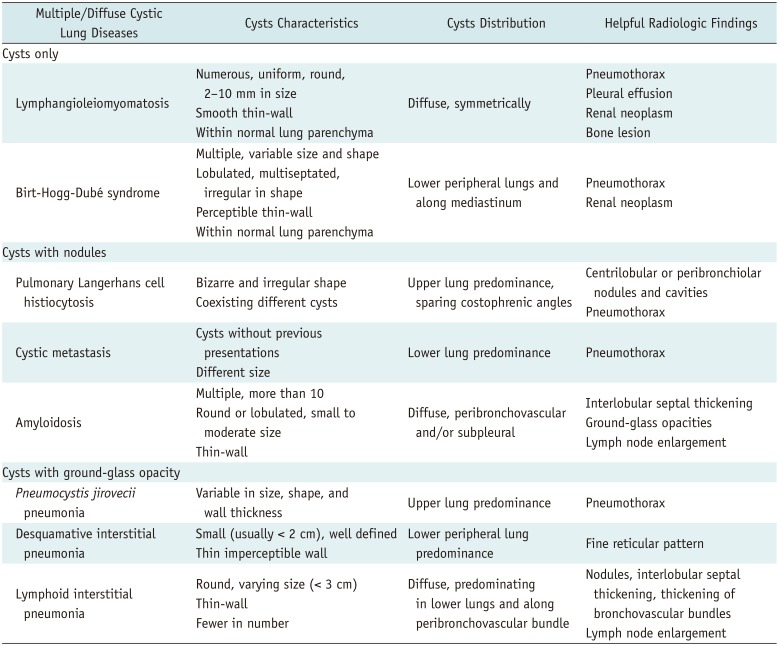

For step three, multiple/diffuse cysts can be further categorized according to the presence or absence of other associated radiologic findings. Radiologists should carefully review CT images for cysts as well as identify any other associated findings such as nodules, ground-glass opacity, or extrapulmonary lesions in areas visible in chest CT (Table 2).

In this step, we will provide a detailed review of diseases characterized by multiple/diffuse cysts only. Multiple/diffuse cysts with associated radiologic findings will be reviewed in the following step.

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is a rare disease that predominantly affects the lung parenchyma of women of childbearing age (181920). LAM can occur sporadically, but is more common in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC-LAM) (202122). TSC-LAM is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous syndrome characterized by hamartoma formation in multiple organs (21). Pathologically, typical findings are nodules or small clusters of smooth muscle cells (LAM cells) near cystic lesions and around terminal bronchioles, alveolar walls, pulmonary vessels, and the lymphatics (2023). Cysts in the lung parenchyma may be the result of terminal bronchiole obstruction by LAM cells with associated air-trapping, which is thought to cause progressive dilatation of the distal airspaces leading to cyst formation and/or from degradation of the lung parenchyma due to an imbalance between proteases and protease inhibitors (20). Lymphatic obstruction may result in chylous pleural effusion, chylous ascites, or both. Spontaneous or recurrent pneumothorax is the presenting finding in up to 50% of LAM patients (22).

Radiologically, lung cysts have been seen in 100% of patients with LAM reported to date (19). Cysts are typically numerous, thin-walled, well-circumscribed, and diffusely and symmetrically distributed throughout the lungs without lobar predominance. Cysts are typically round or ovoid and are usually 2–10 mm in diameter, but can occasionally be as large as 30 mm. The lung parenchyma between cysts is typically normal (Fig. 7) (192022). LAM can appear with small nodules, reticulation, or ground-glass opacity (1922); however, these presentations are rare. Other extrapulmonary findings, such as pneumothorax, chylothorax, chylous ascites, bony sclerotic lesion, and renal tumor can be seen on chest CT (192021).

Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome (BHD) is an uncommon, autosomal-dominant, multiorgan systemic condition characterized clinically by fibrofolliculomas, pulmonary cysts, and renal neoplasms (24252627). On CT, more than 80% of adult patients with BHD have multiple lung cysts, and lung parenchyma except for multiple lung cysts generally appears normal (224). The presence of lung cysts is significantly associated with spontaneous pneumothorax (2). The histological features of BHD cysts are generally indistinguishable from those of emphysema (2). All patients with pulmonary manifestations of BHD have characteristic skin and/or renal lesions or a family history. Therefore, the presence of spontaneous pneumothorax in a young adult, with a family history of pneumothorax, skin lesions, or renal tumors, should indicate the possibility of BHD (2).

Radiologically, multiple thin-walled lung cysts are predominantly seen in lower, peripheral lung zones and along the mediastinum (Fig. 8) (26). These cysts are surrounded by normal lung parenchyma. The shape and size of cysts are variable; they can be round, oval, lentiform, lobulated, or irregularly shaped, and generally have perceptible thin walls. Large cysts, particularly those in the lower lungs, have a lobulated, multiseptated appearance (26). Predominant distribution of cysts in the lower medial lung zone is a characteristic finding. Cysts abutting or including the proximal portions of lower pulmonary arteries or veins may also exist (28).

Since BHD and LAM share some clinical manifestations, such as lung cysts with pneumothorax, renal tumors, and occasionally skin lesions, differential diagnosis of these two diseases can be problematic, especially in female patients. Quantitative analysis of lung cysts for differentiation of these two diseases yields significantly different findings, and the independent parameters for differentiating the two diseases are a family history of pneumothorax, zonal predominance of cysts, diffusing capacity, and size of the cysts (25). Lung cysts in BHD are predominantly distributed in the lower peripheral lung zones and along the mediastinum, generally larger in size and fewer in number, in comparison with lung cysts in LAM.

The next step is to identify radiological findings accompanying the cysts. We divide multiple/diffuse cysts into two categories according to associated radiological findings as follows: multiple/diffuse cysts with nodules and multiple/diffuse cysts with ground-glass opacity.

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis (PLCH) is a rare interstitial lung disease that typically affects young adults and is associated with cigarette smoking (2022). PLCH is characterized by peribronchiolar infiltration by Langerhans and inflammatory cells and formation of granulomas, leading to stellate interstitial nodules (2229). These stellate nodules can later cavitate, resulting in bronchial dilatation and formation of thin- and thick-walled cysts and cavities. These cysts may coalesce, forming bizarre shapes. Pathologically, temporal heterogeneity is typically present. Early interstitial infiltration of Langerhans cell histiocytosis cells is followed by nodules with variable numbers of lymphocytes and eosinophils. As the disease progresses, early cellular nodules are replaced by fibroblastic proliferation in a centripetal fashion, eventually leaving fibrotic scars surrounded by enlarged airspaces (2229).

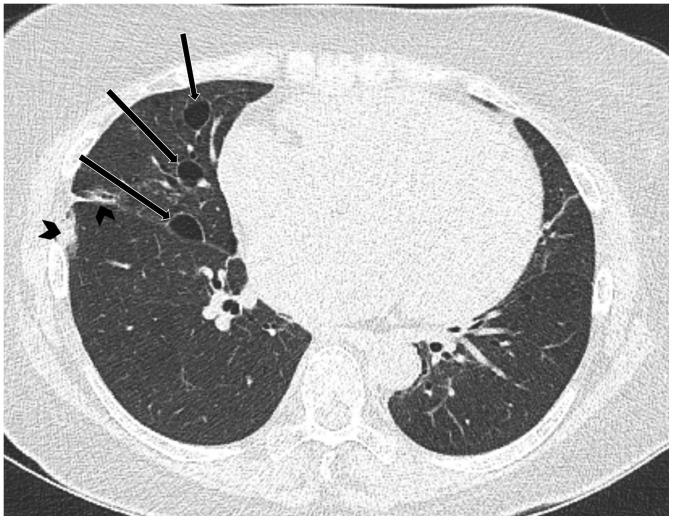

Radiologically, nodules are the predominant features in the early stages, while cysts tend to develop later. In the early stages, small (1–10 mm) irregularly shaped nodules appear in a bilateral symmetric pattern with upper-middle lung dominance and a spared lung base and costophrenic angle. As the disease progresses, cystic degeneration appears as round or oval to bizarre with thin-wall and associated nodules (Fig. 9) (202229). Cysts usually measure < 10 mm in diameter but may be as large as 20 mm. They may manifest as round or ovoid cystic spaces or exhibit bizarre configurations with twolobed, clover leaf, septated, and branching morphologies that resemble bronchiectasis. Cyst walls may be thin and barely perceptible or may appear thick, irregular, and nodular, depending on the degree of nodule cavitation. Different cyst appearances may coexist. Bizarre-shaped cysts associated with nodules predominantly in the upper lung are a key imaging discriminator for PLCH in a young smoker.

Cystic lung metastasis is most frequently seen in patients with angiosarcoma or squamous cell carcinoma mainly in the head and neck (2030). In a study of lung metastasis from angiosarcoma, nodules were seen in 85% and multiple cysts were seen in 55% of patients (30). There are four possible mechanisms for cyst formation. First, excavation of solid nodular lesions can induce cyst formation. Second, infiltration of malignant cells into the walls of pre-existing bullous lung tissue can result in cyst formation. Third, infiltration of tumor cells into the walls of air sacs and the ball-valve effect can cause cystic distension. Last, tumor cell proliferation can form blood-filled cystic spaces (31).

Radiologically, multiple solid nodules and multiple thinwalled cysts, often admixed with hemorrhagic change, are common features of metastatic angiosarcoma (31). Cystic metastasis from angiosarcomas shows variability in the walls, air-fluid levels, and vessels or bronchi penetrating the cysts (Fig. 10) (30). As with other lung metastases, cystic metastasis tends to show different sizes and a basilar predominance (32). Pneumothorax is a potential complication of cystic metastasis.

A patient's previous malignancy history is critical for diagnosis. If new lung cysts are detected in patients with a known malignancy, cystic metastasis should be considered, and adequate tissue confirmation is required for diagnosis.

Amyloidosis is a rare disease characterized by extracellular deposition of abnormal insoluble proteins (3334). Characteristically, the amyloid deposit shows apple-green birefringence with Congo red stain and under polarized light (35). The thorax can be affected, and pulmonary involvement of amyloidosis is relatively rare (35). Pulmonary amyloidosis can present with cystic lung disease, and amyloid-associated cystic lung disease is rare. Amyloid-associated cystic lung disease can occur with Sjögren's syndrome and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (34). Narrowing of the airways from surrounding inflammation or amyloid protein deposits may lead to the development of a check valve phenomenon. Alternatively, an ischemic process with amyloid deposition causing capillary disruption may lead to alveolar wall destruction and cyst formation (222).

Radiologically, lung cysts are commonly numerous (more than 10), are often peribronchovascular or subpleural, and are frequently associated with nodular lesions that are often calcified (34). Cysts tend to be multiple, round or lobulated, small to moderate in size, and thin-walled (34). Other associated findings include interlobular septal thickening, honeycombing, ground-glass opacity, circumferential thickening of the tracheal wall, and lymphadenopathy (34).

Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP) is a fungal infection that has a strong association with immunocompromised conditions such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (93236).

Radiologically, ground-glass opacity indicating acute pneumonia is the dominant feature of this condition (36). The pattern of these opacities is often bilateral, multifocal, and mainly symmetrical, and distributed in the central portions of the lungs. Opacities can predominate in the upper lung zones in patients receiving prophylactic therapy for this infection. Thin-walled cysts are now recognized as a relatively common manifestation of this infection and are reported in as many as one-third of all patients (3637). Cysts are usually variable in size, shape, and wall thickness, and are usually multiple and bilateral, subpleurally or intraparenchymally located, and are predominantly in the upper lung zone (Fig. 11) (93637). PCP is associated with an increased incidence of spontaneous pneumothorax, which is believed to occur in association with ruptured subpleural cysts (37).

Desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP) is characterized by the accumulation of numerous pigmented macrophages within most of the distal airspace of the lung (38). According to the international multidisciplinary classification of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, DIP is classified as a smoking-related interstitial lung disease (39). Up to 90% of DIP patients have a smoking history, but other conditions besides smoking, such as occupational exposure to certain inhaled toxins, drugs, viral illnesses, and autoimmune diseases, can also cause DIP (38).

Radiologically, DIP presents with patchy ground-glass opacity with a predilection for the basal and peripheral lungs. Reticular density may also be present. Small (usually < 2 cm), well-defined, thin-walled cysts are seen within ground-glass opacity, which is an important finding in DIP (Fig. 12) (134041). Honeycombing is also possible, but uncommon (42). Cysts in DIP have imperceptible walls, and they are mostly discrete but occasionally can be clustered and are surrounded by ground-glass opacity. Cysts in DIP are believed to represent dilated bronchioles and alveolar ducts, and in the later stages of DIP, cysts may also represent early centrilobular emphysema or honeycombing (22). The presence of small cysts admixed within groundglass opacity is a unique feature of DIP. This feature is reported in approximately one-third of DIP patients (38).

Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP) is an uncommon benign polyclonal lymphoproliferative disease (2043). Idiopathic LIP is categorized as a rare idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (39). Most cases of LIP are associated with various underlying disorders, including HIV infection, connective tissue diseases such as Sjögren's syndrome, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, and systemic lupus erythematosus (2039). Pathologically, diffuse interstitial infiltration of small polyclonal lymphocytes and plasma cells is seen (2022). Cysts result from ischemia due to vascular obstruction, postobstructive alveolar dilatation, or compression of bronchioles by lymphoid tissue leading to a check valve mechanism (20).

Radiologically, a combination of ground-glass opacity, poorly defined centrilobular nodules, small subpleural nodules, interlobular septal thickening, thickening of the bronchovascular bundles, and scattered cysts in lower lungs are seen (Fig. 13) (2044). Lung cysts are present in up to 68% of patients; they are usually fewer in number but are distributed diffusely in both lungs, although they are often subpleural and peribronchovascular (44). Cysts in LIP are generally < 3 cm in diameter, are variable in shape, and may be the sole manifestation of this disease. In most cases, follow-up CT reveals the resolution of groundglass opacity, and cysts are the only residual finding in more chronic cases. Lymphadenopathy can be present, but pleural effusion or airspace consolidation are extremely rare (43). The diagnosis of LIP should be considered in patients with lung cysts and immunological abnormalities. The appearance of a few scattered cysts in a patient with Sjögren's syndrome is very likely to indicate LIP.

A variety of pathophysiological processes and diseases can present as lung cysts and cystic lung diseases. CT remains the single most useful noninvasive diagnostic tool for evaluating cystic lung diseases. Radiologists should know how to approach cystic lung diseases using only radiologic features, although definite diagnosis may require clinical correlation and sometimes biopsy for histologic diagnosis.

This stepwise radiologic approach offers an easy method for accurate diagnosis of various cystic lung diseases. Accurate radiologic diagnosis is essential for better management of patients with cystic lung diseases.

References

1. Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Müller NL, Remy J. Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology. 2008; 246:697–722. PMID: 18195376.

2. Gupta N, Vassallo R, Wikenheiser-Brokamp KA, McCormack FX. Diffuse cystic lung disease. Part II. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015; 192:17–29. PMID: 25906201.

3. Ryu JH, Swensen SJ. Cystic and cavitary lung diseases: focal and diffuse. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003; 78:744–752. PMID: 12934786.

4. Gafoor K, Patel S, Girvin F, Gupta N, Naidich D, Machnicki S, et al. Cavitary lung diseases: a clinical-radiologic algorithmic approach. Chest. 2018; 153:1443–1465. PMID: 29518379.

5. Parkar AP, Kandiah P. Differential diagnosis of cavitary lung lesions. J Belg Soc Radiol. 2016; 100:100. PMID: 30151493.

6. Beigelman-Aubry C, Godet C, Caumes E. Lung infections: the radiologist's perspective. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2012; 93:431–440. PMID: 22658280.

7. Lynch DA, Austin JH, Hogg JC, Grenier PA, Kauczor HU, Bankier AA, et al. CT-definable subtypes of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a statement of the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2015; 277:192–205. PMID: 25961632.

8. Takahashi M, Fukuoka J, Nitta N, Takazakura R, Nagatani Y, Murakami Y, et al. Imaging of pulmonary emphysema: a pictorial review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2008; 3:193–204. PMID: 18686729.

9. Ha D, Yadav R, Mazzone PJ. Cystic lung disease: systematic, stepwise diagnosis. Cleve Clin J Med. 2015; 82:115–127. PMID: 25897602.

10. Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Myers JL, Richeldi L, Ryerson CJ, Lederer DJ, et al. American Thoracic Society. European Respiratory Society. Japanese Respiratory Society. Latin American Thoracic Society. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018; 198:e44–e68. PMID: 30168753.

11. Copley SJ, Wells AU, Hawtin KE, Gibson DJ, Hodson JM, Jacques AE, et al. Lung morphology in the elderly: comparative CT study of subjects over 75 years old versus those under 55 years old. Radiology. 2009; 251:566–573. PMID: 19401580.

12. Araki T, Nishino M, Gao W, Dupuis J, Putman RK, Washko GR, et al. Pulmonary cysts identified on chest CT: are they part of aging change or of clinical significance? Thorax. 2015; 70:1156–1162. PMID: 26514407.

13. Raoof S, Bondalapati P, Vydyula R, Ryu JH, Gupta N, Raoof S, et al. Cystic lung diseases: algorithmic approach. Chest. 2016; 150:945–965. PMID: 27180915.

14. Biyyam DR, Chapman T, Ferguson MR, Deutsch G, Dighe MK. Congenital lung abnormalities: embryologic features, prenatal diagnosis, and postnatal radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2010; 30:1721–1738. PMID: 21071385.

15. Odev K, Guler I, Altinok T, Pekcan S, Batur A, Ozbiner H. Cystic and cavitary lung lesions in children: radiologic findings with pathologic correlation. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2013; 3:60. PMID: 24605255.

16. Zylak CJ, Eyler WR, Spizarny DL, Stone CH. Developmental lung anomalies in the adult: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2002; 22 Spec No:S25–S43. PMID: 12376599.

17. Yoon YC, Lee KS, Kim TS, Kim J, Shim YM, Han J. Intrapulmonary bronchogenic cyst: CT and pathologic findings in five adult patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002; 179:167–170. PMID: 12076928.

18. Kalassian KG, Doyle R, Kao P, Ruoss S, Raffin TA. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: new insights. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997; 155:1183–1186. PMID: 9105053.

19. Pallisa E, Sanz P, Roman A, Majó J, Andreu J, Cáceres J. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: pulmonary and abdominal findings with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2002; 22 Spec No:S185–S198. PMID: 12376610.

20. Baldi BG, Carvalho CRR, Dias OM, Marchiori E, Hochhegger B. Diffuse cystic lung diseases: differential diagnosis. J Bras Pneumol. 2017; 43:140–149. PMID: 28538782.

21. Umeoka S, Koyama T, Miki Y, Akai M, Tsutsui K, Togashi K. Pictorial review of tuberous sclerosis in various organs. Radiographics. 2008; 28:e32. PMID: 18772274.

22. Seaman DM, Meyer CA, Gilman MD, McCormack FX. Diffuse cystic lung disease at high-resolution CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011; 196:1305–1311. PMID: 21606293.

23. Kitaichi M, Nishimura K, Itoh H, Izumi T. Pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a report of 46 patients including a clinicopathologic study of prognostic factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995; 151(2 Pt 1):527–533. PMID: 7842216.

24. Menko FH, van Steensel MA, Giraud S, Friis-Hansen L, Richard S, Ungari S, et al. European BHD Consortium. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: diagnosis and management. Lancet Oncol. 2009; 10:1199–1206. PMID: 19959076.

25. Tobino K, Hirai T, Johkoh T, Kurihara M, Fujimoto K, Tomiyama N, et al. Differentiation between Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome and lymphangioleiomyomatosis: quantitative analysis of pulmonary cysts on computed tomography of the chest in 66 females. Eur J Radiol. 2012; 81:1340–1346. PMID: 21550193.

26. Agarwal PP, Gross BH, Holloway BJ, Seely J, Stark P, Kazerooni EA. Thoracic CT findings in Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011; 196:349–352. PMID: 21257886.

27. Toro JR, Pautler SE, Stewart L, Glenn GM, Weinreich M, Toure O, et al. Lung cysts, spontaneous pneumothorax, and genetic associations in 89 families with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007; 175:1044–1053. PMID: 17322109.

28. Tobino K, Gunji Y, Kurihara M, Kunogi M, Koike K, Tomiyama N, et al. Characteristics of pulmonary cysts in Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: thin-section CT findings of the chest in 12 patients. Eur J Radiol. 2011; 77:403–409. PMID: 19782489.

29. Abbott GF, Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Franks TJ, Frazier AA, Galvin JR. From the archives of the AFIP: pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Radiographics. 2004; 24:821–841. PMID: 15143231.

30. Yogi A, Miyara T, Ogawa K, Iraha S, Matori S, Haranaga S, et al. Pulmonary metastases from angiosarcoma: a spectrum of CT findings. Acta Radiol. 2016; 57:41–46. PMID: 25711232.

31. Tateishi U, Hasegawa T, Kusumoto M, Yamazaki N, Iinuma G, Muramatsu Y, et al. Metastatic angiosarcoma of the lung: spectrum of CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003; 180:1671–1674. PMID: 12760941.

32. Cantin L, Bankier AA, Eisenberg RL. Multiple cystlike lung lesions in the adult. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010; 194:W1–W11. PMID: 20028879.

33. Czeyda-Pommersheim F, Hwang M, Chen SS, Strollo D, Fuhrman C, Bhalla S. Amyloidosis: modern cross-sectional imaging. Radiographics. 2015; 35:1381–1392. PMID: 26230754.

34. Zamora AC, White DB, Sykes AM, Hoskote SS, Moua T, Yi ES, et al. Amyloid-associated cystic lung disease. Chest. 2016; 149:1223–1233. PMID: 26513525.

35. Georgiades CS, Neyman EG, Barish MA, Fishman EK. Amyloidosis: review and CT manifestations. Radiographics. 2004; 24:405–416. PMID: 15026589.

36. Kanne JP, Yandow DR, Meyer CA. Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia: high-resolution CT findings in patients with and without HIV infection. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012; 198:W555–W561. PMID: 22623570.

37. Boiselle PM, Crans CA Jr, Kaplan MA. The changing face of pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in AIDS patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999; 172:1301–1309. PMID: 10227507.

38. Godbert B, Wissler MP, Vignaud JM. Desquamative interstitial pneumonia: an analytic review with an emphasis on aetiology. Eur Respir Rev. 2013; 22:117–123. PMID: 23728865.

39. Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, King TE Jr, Lynch DA, Nicholson AG, ATS/ERS Committee on Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013; 188:733–748. PMID: 24032382.

40. Gupta N, Vassallo R, Wikenheiser-Brokamp KA, McCormack FX. Diffuse cystic lung disease. Part I. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015; 191:1354–1366. PMID: 25906089.

41. Gupta N, Colby TV, Meyer CA, McCormack FX, Wikenheiser-Brokamp KA. Smoking-related diffuse cystic lung disease. Chest. 2018; 154:e31–e35. PMID: 30080520.

42. Attili AK, Kazerooni EA, Gross BH, Flaherty KR, Myers JL, Martinez FJ. Smoking-related interstitial lung disease: radiologic-clinical-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2008; 28:1383–1396. discussion 1396–1398. PMID: 18794314.

43. Sirajuddin A, Raparia K, Lewis VA, Franks TJ, Dhand S, Galvin JR, et al. Primary pulmonary lymphoid lesions: radiologic and pathologic findings. Radiographics. 2016; 36:53–70. PMID: 26761531.

44. Johkoh T, Müller NL, Pickford HA, Hartman TE, Ichikado K, Akira M, et al. Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia: thin-section CT findings in 22 patients. Radiology. 1999; 212:567–572. PMID: 10429719.

Fig. 1

Stepwise radiologic diagnostic approach to cystic lung diseases.

BHD = Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, DIP = desquamative interstitial pneumonia, GGO = ground-glass opacity, LAM = lymphangioleiomyomatosis, LIP = lymphoid interstitial pneumonia, PCP = pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, PLCH = pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis

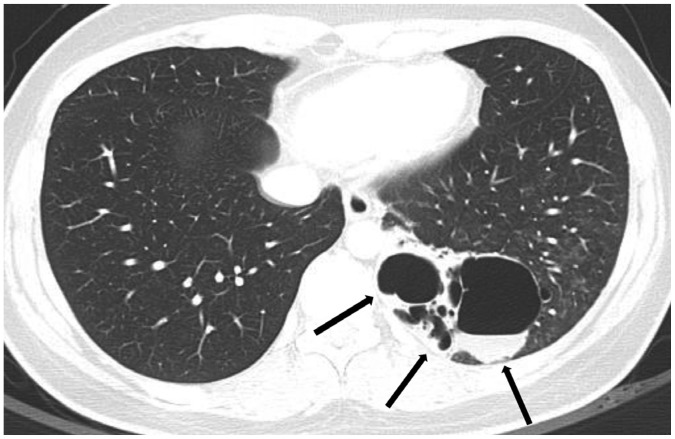

Fig. 2

Single or several air-filled lesions in localized area.

A. Cyst: round air-filled lesion with well-defined thin wall surrounded by normal lung (arrow). B. Cavity: air-filled lesion with thick wall within mass. C. Bulla: air-filled lesion, more than 1 cm in diameter, bounded by very thin imperceptible wall and associated with adjacent centrilobular emphysema. D. Pneumatocele: thin-walled, air-filled lesion (arrow) caused by pneumonia.

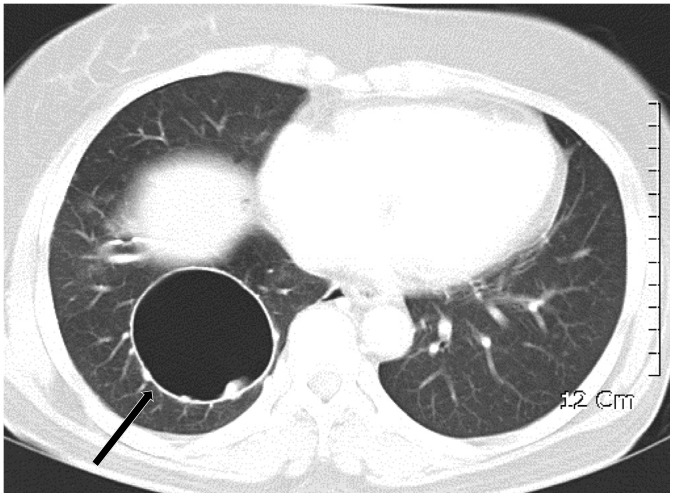

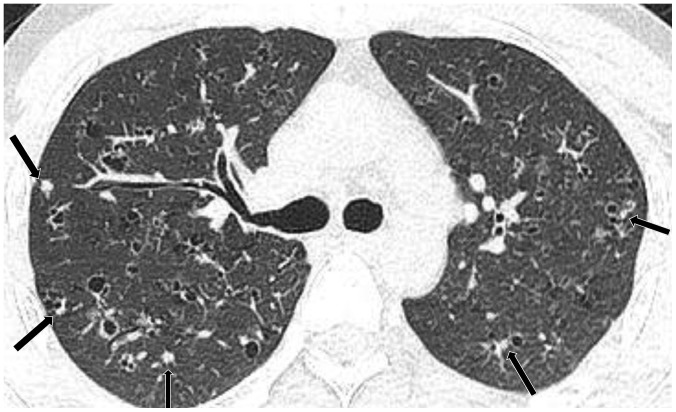

Fig. 3

Multiple or numerous air-filled lesions distributed in both lungs.

A. Multiple and diffuse cysts in PLCH: multiple cysts of variable sizes and shapes with thin wall. B. Centrilobular emphysema: centrilobular lucencies without distinct walls, central dot within lucency represents branch of pulmonary artery. C. Honeycombing: multiple rows of air-filled spaces with thick wall clustered in subpleural region. D. Cystic bronchiectasis: tubular rather than spherical dimensions with branching pattern and associated bronchial wall thickening.

Fig. 4

Incidental cyst in 73-year-old woman.

CT shows round 16-mm-sized thin-walled cyst (arrow) in right middle lobe.

Fig. 5

Congenital pulmonary airway malformation in 18-year-old woman.

CT shows complex cystic mass (arrows) in left lower lobe, where largest cyst is larger than 2 cm. Lobectomy confirmed congenital pulmonary airway malformation.

Fig. 6

Bronchogenic cyst in 55-year-old woman.

CT shows well-defined air-filled cyst (arrow) in right lower lobe, suggesting bronchogenic cyst. Surgical resection confirmed bronchogenic cyst.

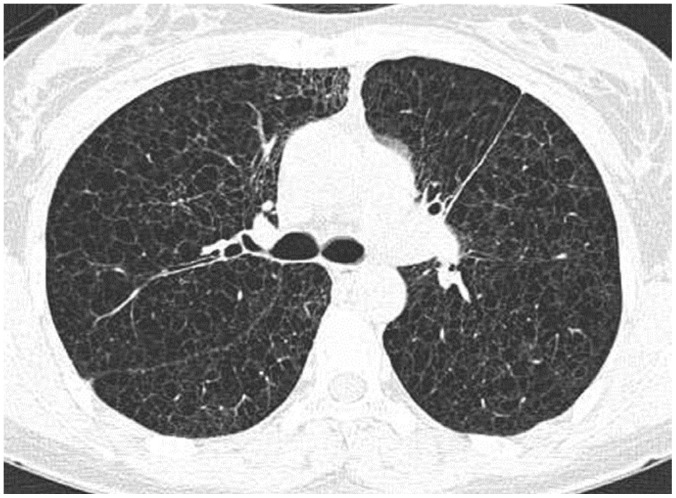

Fig. 7

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis in 28-year-old woman.

CT shows numerous cysts in both lungs. Cysts are round or ovoid and relatively uniform in size and shape. Cysts are diffusely distributed without zone predominance in both lungs. Lung biopsy was done through video-assisted thoracic surgery and lymphangioleiomyomatosis was confirmed histologically.

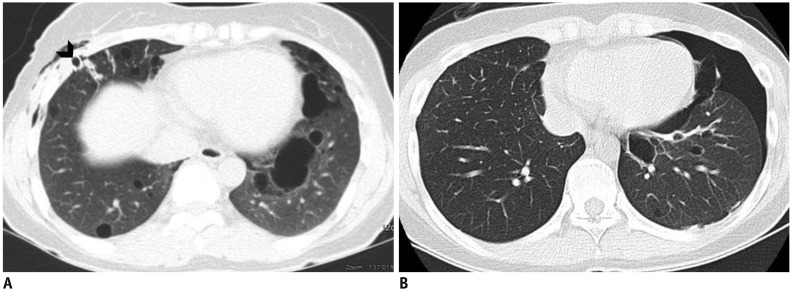

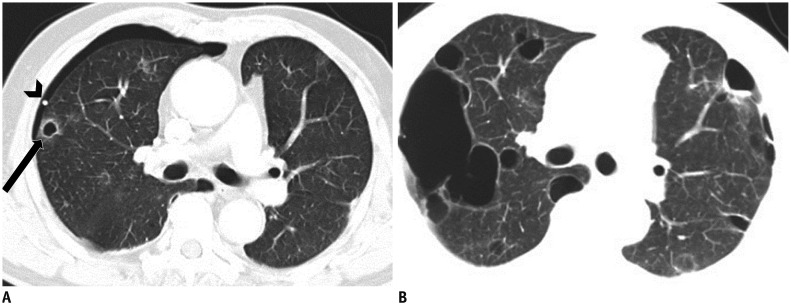

Fig. 8

Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome with recurrent pneumothorax in 47-year-old woman (A) and 22-year-old woman (B) who were mother and daughter.

A. CT shows multiple, variable-sized, thin-walled cysts with lower subpleural lung predominance. Chest drainage tube (arrow head) is noted in right hemithorax for pneumothorax. B. CT shows multiple thin-walled cysts of various sizes and shapes in both lungs, with left lower lung dominance, and pneumothorax in left hemithorax.

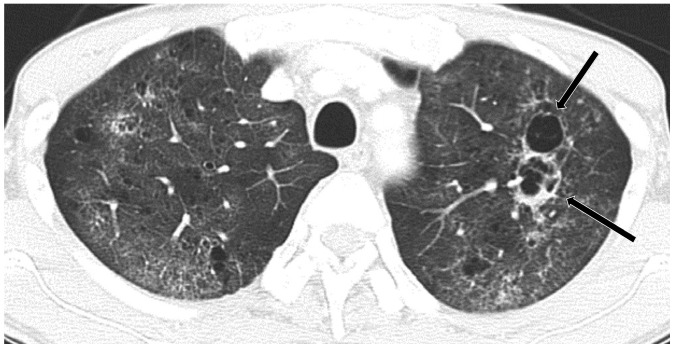

Fig. 9

PLCH in 22-year-old male smoker.

CT shows multiple, irregular, and round, thick- and thin-walled cysts with small irregular nodules (arrows) in both lungs, sparing lung bases and costophrenic angles (not shown), suggestive of PLCH, which was subsequently confirmed histologically.

Fig. 10

Cystic metastasis from scalp angiosarcoma with recurrent pneumothorax in 71-year-old man.

A. CT shows multiple cystic or cavitary nodules (arrow) that were histologically confirmed as metastasis. Pneumothorax is noted with drainage tube (arrow head). B. CT performed after 2 months shows variable-sized thin-walled cystic lesions in both lungs that greatly increased in size and number as compared with previous CT scan (A).

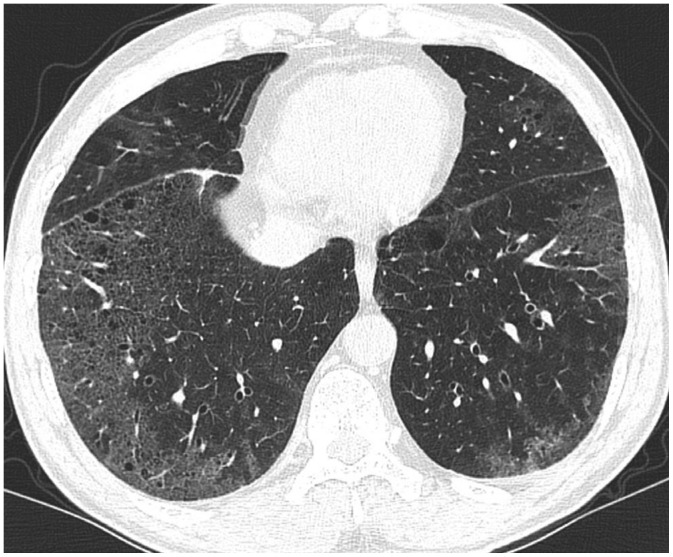

Fig. 11

Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in 46-year-old HIV infected man with left pneumothorax.

CT in upper lung zone shows multiple irregular thick-walled and thin-walled cysts (arrows) on background of bilateral diffuse GGO. HIV= human immunodeficiency virus

Fig. 12

Desquamative interstitial pneumonia in 52-year-old smoker.

CT shows GGO with tiny cysts in both lungs, mainly lower peripheral lungs, almost symmetrically distributed. Surgical lung biopsy confirmed desquamative interstitial pneumonia histologically.

Fig. 13

Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia in 51-year-old woman with Sjögren's syndrome.

CT shows diffuse faint GGO and several cysts (arrows) in right lung. Cysts are thin-walled and distributed randomly. Previous surgical scars (arrowheads) are noted in subpleural region of right middle and lower lobes.

Table 1

Radiologic Distinctions for Air-Filled Lung Lesions

Table 2

Radiologic Distinctions for Multiple/Diffuse Cystic Lung Diseases

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download