Abstract

Ischemic colitis primarily affects the elderly with underlying disease, but it rarely occurs in young adults with risk factors, such as coagulopathy or vascular disorder. Moreover, it is extremely rare in the very young without risk factors. This paper presents a patient with ischemic colitis associated with heat stroke and rhabdomyolysis after intense exercise under high-temperature conditions. A 20-year-old man presented with mental deterioration after a vigorous soccer game for more than 30 minutes in sweltering weather. He also presented with hematochezia with abdominal pain. The laboratory tests revealed the following: AST 515 U/L, ALT 269 U/L, creatine kinase 23,181 U/L, BUN 29.1 mg/dL, creatinine 1.55 mg/dL, and red blood cell >50/high-power field in urine analysis. Sigmoidoscopy showed ischemic changes at the rectum and rectosigmoid junction. A diagnosis of ischemic colitis and rhabdomyolysis was made, and the patient recovered after conservative and fluid therapy. This case showed that a diagnosis of ischemic colitis should be considered in patients who present with abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea after intense exercise, and appropriate treatment should be initiated immediately.

Ischemic colitis (IC) is an inflammatory condition of the large intestine that results from reduced blood flow. The condition typically occurs in elderly patients with comorbid cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus.1 Conditions that can decrease the circulation of blood flow are also associated with IC.12 IC is rarely reported in young individuals; however, hypercoagulability, thrombophilia sickle cell disease, cocaine or metanephrines abuse, or hypovolemia due to environmental causes, such as vigorous physical exercise or heat, could be predisposing factors for IC in young patients.34 Extreme exercise, such as long-distance running or triathlon competitions, can cause a range of gastrointestinal symptoms, including intestinal ischemia in 20% to 50% of cases.45 This paper presents a case of acute IC accompanied by rhabdomyolysis in a young man after heat stroke caused by vigorous physical exercise under extreme-temperature conditions.

A 20-year-old man presented to the emergency department with mental deterioration. The patient had played vigorous soccer for more than 30 minutes in sweltering weather and felt dizziness with nausea during the resting time. He was found unconscious in the street, having passed out on his way home. His medical records showed that he had had a problem with urination at night since a car accident at the age of four and had been on medication since then; no other specific medical records were known. At the time of admission, his vital signs were as follows: body temperature, 39.5℃; blood pressure, 120/70 mmHg; heart rate, 132 beats per minute; and respiratory rate, 28 breaths per minute. The initial laboratory findings revealed the following: white blood cell 16,400/µL, hemoglobin 14.4 g/dL, hematocrit 42%, AST 36 U/L, ALT 26 U/L, BUN 20.7 mg/dL, creatinine 1.76 mg/dL, creatine kinase 421 U/L, and uric acid 11.1 mg/dL. He regained consciousness quickly after admission, but the high fever (39.5℃) persisted, accompanied by violent and irritable behavior. Based on the laboratory findings and clinical manifestation, he was diagnosed initially with heat stroke and was treated by cooling with an ice bag and fluid replacement. On the second day of hospitalization, his body temperature stabilized at 37.4℃, and the laboratory tests revealed AST 515 U/L, ALT 269 U/L, creatine kinase 23,181 U/L, BUN 29.1 mg/dL, creatinine 1.55 mg/dL, and red blood cell >50/high-power field in urine analysis. In addition, he presented with hematochezia and abdominal pain.

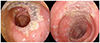

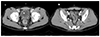

The sigmoidoscopy showed necrosis of the mucosa at the rectum and rectosigmoid junction (Fig. 1). The abdominal CT on the third day of hospitalization revealed mild wall thickening along the rectum and rectosigmoid junction to the splenic flexure area with irregular mucosal enhancement at the rectum and rectosigmoid junction (Fig. 2).

A diagnosis of IC and rhabdomyolysis was made. The patient was treated with conservative and fluid therapy; his symptoms improved gradually and the laboratory findings were normalized. The follow-up sigmoidoscopy performed six weeks later revealed a completely normal colonic mucosa (Fig. 3).

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient who participated in this study.

IC is the most common form of intestinal ischemia, occurring mainly in elderly patients; however, it also occurs in young adults with no underlying disease, albeit rarely. One Japanese study reported that 15% of IC occurred in the young age group between 20 to 45 years.6 This study showed that the smoking habit and hyperuricemia are associated with IC in young adults.6

IC was reported to occur in young adults after extreme exercise (e.g., marathon running, triathlon competition, etc.) accompanied by dehydration, high temperature, and exhaustion.4 The patient showed sudden mental deterioration after extreme exercise performed in hot weather, indicating heat stroke, and it could be one of the factors leading to IC. The increased sympathetic and decreased vagal activity during exercise causes a decrease in splanchnic blood flow and increased muscle blood flow.7 Ischemia of the visceral organ can occur if exercise is too intense and prolonged or is superimposed by hyperthermia, dehydration, and alterations in blood viscosity.48 The patient's symptoms were accompanied by heat stroke and rhabdomyolysis, which has never been reported. Visceral blood flows can be decreased significantly during and after exercise by up to 80%.910 Studies with transcutaneous Doppler ultrasound revealed a 43% decrease in visceral blood flow immediately after treadmill exercise (speed 5 km/h, gradient 20%, duration 15 minutes) and up to 50% after submaximal cycling.1112 This decrease in visceral flow occurred irrespective of their exercise capacity or training status.10 Drugs, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the oral contraceptive pill, also might be a risk factor for IC associated with exercise.813

The typical symptoms of IC after exercise are vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and hematochezia.48131415 In addition to IC, a range of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, including nausea, regurgitation, belching, epigastric discomfort, diarrhea, urge to defecate, GI cramps, and flatulence, are associated with exercise, and women appear to be commonly affected.571415 The frequency of GI symptoms tends to increase in marathon running and triathlons compared to sports, such as cycling, rowing, and swimming.71516 A previous study of long-distance runners reported a range of GI injuries on endoscopy, such as gastritis, esophagitis, gastric ulcer, and multiple erosions at the splenic flexure.17 The following study showed that ranitidine prophylaxis is effective in preventing gastric mucosal injury and GI bleeding in runners.5

Generally, in most cases of IC after extreme exercise, the individuals usually recover without sequelae.113 On the other hand, some cases experienced more severe complications, including colonic infarction, peritonitis, perforation, sepsis leading to laparotomy, and hemicolectomy.48

A very rare case of exercise-associated IC accompanied by rhabdomyolysis was encountered. Overall, a diagnosis of IC should be considered in patients who present with abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea after intense exercise, and appropriate treatment should be initiated immediately.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Sigmoidoscopy taken on the second day of hospitalization revealed necrosis in the rectum and rectosigmoid junctional colonic mucosa.

References

1. Brandt LJ, Feuerstadt P, Longstreth GF, Boley SJ. American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: epidemiology, risk factors, patterns of presentation, diagnosis, and management of colon ischemia (CI). Am J Gastroenterol. 2015; 110:18–44.

2. Yoon BW, Park JS, Woo YS, et al. Severe ischemic colitis from gastric ulcer bleeding-induced shock in patient with end stage renal disease receiving hemodialysis. Korean J Helicobacter Up Gastrointest Res. 2016; 16:165–168.

3. Sanchez LD, Tracy JA, Berkoff D, Pedrosa I. Ischemic colitis in marathon runners: a case-based review. J Emerg Med. 2006; 30:321–326.

5. Choi SJ, Kim YS, Chae JR, et al. Effects of ranitidine for exercise induced gastric mucosal changes and bleeding. World J Gastroenterol. 2006; 12:2579–2583.

6. Kimura T, Shinji A, Horiuchi A, et al. Clinical characteristics of young-onset ischemic colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2012; 57:1652–1659.

7. Brouns F, Beckers E. Is the gut an athletic organ? Digestion, absorption and exercise. Sports Med. 1993; 15:242–257.

8. Cohen DC, Winstanley A, Engledow A, Windsor AC, Skipworth JR. Marathon-induced ischemic colitis: why running is not always good for you. Am J Emerg Med. 2009; 27:255.e5–255.e7.

9. Rowell LB. Human cardiovascular adjustments to exercise and thermal stress. Physiol Rev. 1974; 54:75–159.

10. Clausen JP. Effect of physical training on cardiovascular adjustments to exercise in man. Physiol Rev. 1977; 57:779–815.

12. Perko MJ, Nielsen HB, Skak C, Clemmesen JO, Schroeder TV, Secher NH. Mesenteric, coeliac and splanchnic blood flow in humans during exercise. J Physiol. 1998; 513(Pt 3):907–913.

13. Lucas W, Schroy PC 3rd. Reversible ischemic colitis in a high endurance athlete. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998; 93:2231–2234.

14. Moses FM. The effect of exercise on the gastrointestinal tract. Sports Med. 1990; 9:159–172.

15. de Oliveira EP, Burini RC. The impact of physical exercise on the gastrointestinal tract. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2009; 12:533–538.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download