INTRODUCTION

Ureaplasma species, including

Ureaplasma urealyticum (UU) and

Ureaplasma parvum (UP), are classified as small sized bacteria [

12]. The simple genomic structures and limited metabolic activity impose a close and long-term parasitic interaction between the bacteria and the infected cells [

12]. In

Ureaplasma-related infections, clinical symptoms and signs are often mild or even asymptomatic, making it very difficult to characterize their pathogenicity. Similarly, their parasitic nature and indolent course in infected host cells suggest the possibility of

Ureaplasma species as causal pathogens for enigmatic chronic genitourinary infections.

Chronic prostatitis (CP) is one of the most common urological disorders [

3]. Some sexually transmitted infections (STIs) may contribute to the pathogenesis of CP [

345]. For example,

Chlamydia trachomatis that harbor similar genomic simplicity and clinical characteristics as

Ureaplasma are found in prostate tissues in patients with idiopathic CP [

4]. Through a case and control study, the chlamydial infected men reveal increased leukocyte counts in expressed prostatic secretion (EPS) and exacerbated CP-associated pain severity in men with CP. These findings clearly suggest the association of urinary chlamydia infections with CP and consider the possibility of

Ureaplasma species associated CP [

5].

Generally, urologists employ multiplex-nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) from voided urine samples to reveal pathogens for urethritis and CP in men [

6]. Based on the results of these examinations, clinicians must determine the pathogenicity of these bacteria and whether antibiotics are to be prescribed.

While the presence of UU in EPS or in first voided urine sample from CP patients may support the association between

Ureaplasma and CP [

78],

Ureaplasma microbes are not found in the perineal prostate biopsy tissues from idiopathic CP patients [

4]. Furthermore, only a handful of case-control studies that estimate unique pathogenicity of

Ureaplasma infections in the prostate are currently available [

78910]. In addition, we could not find well designed case-control studies with strict diagnostic criteria in defining idiopathic CP [

3]. To understand the specific role of

Ureaplasma species in CP and to design a strict case-control study, we first excluded patients with gonococcal and chlamydia infections through a multiplex NAAT, as well as patients with cystitis or bacterial prostatitis based on a lower urinary localization test. We had also removed the effects of urethral inflammation form the overall data and re-analyzed the subtracted data to enhance statistical power for CP. Finally, we aimed to evaluate the potential role of

Ureaplasma species as causal pathogens in men with CP and clinical features of

Ureaplasma infected CP patients.

DISCUSSION

STIs remain one of the major health issues, causing serious and adverse effects on reproductive health [

13]. Recently developed multiplex NAAT methods for STIs can simultaneously detect multiple causative organisms [

614]. Various scales of multiplex NAAT assays that range from detection of 2–3 to 7 or more STI pathogens have been developed, and the medical practices for executing multiplex NAAT assays have been financially supported by the Korean National Medical Insurance to suppress the spread of STIs [

6]. Consequently, many microbes that are certainly undetected by conventional diagnostic tests have now become recognized by the public health systems.

The overall positive rates for various STIs with multiplex NAAT-based STI tests range from 30% to 50%, depending on study designs [

614]. In particular, previous studies consistently report that the most prevalent microbe detected by such methods is UP and UU [

614]. As

Ureaplasma species are frequently found in coinfections with

Neisseria gonorrhea or

C. trachomatis in urine samples, combinations of these well-known STIs may alter the clinical characteristics of infected individuals and therefore must be ruled out to evaluate the unique characteristics of

Ureaplasma species. Accordingly, cases of

N. gonorrhea and

C. trachomatis infections were excluded from this study. Our study revealed that the infection rate for

Ureaplasma species in the sample population was close to 10%, and UP infections were more frequently found than UU in the NCNG settings.

N. gonorrhea and

C. trachomatis microbes can induce male urethritis or CP, therefore they are eradicated by administering specific antimicrobials [

5915]. However, urethral inflammatory response after

Ureaplasma infections is significantly lower than that of

Mycoplasma genitalium or

C. trachomatis [

16]. In other words, clinical symptoms or signs such as urethral discharge and increased WBC counts in voided urine samples are usually inconsistent following

Ureaplasma infections [

9]. Unfortunately, well designed case-controls studies that may differentiate the role of

Ureaplasma species as causative or bystanders in genitourinary infections are currently not available. Although there is a controversy regarding the pathogenicity of

Ureaplasma species in genitourinary tracts, some physicians conventionally prescribe antibiotics regardless [

17]. Consequently,

Ureaplasma species may be exposed to increased evolutional pressure induced by such frequent medications. Indeed, many

Ureaplasma species harbor resistance to conventional antibiotics [

1819]. Therefore, the clinical significance or pathogenicity of

Ureaplasma infections in male genitourinary organs must be appropriately evaluated to avoid unnecessary treatments.

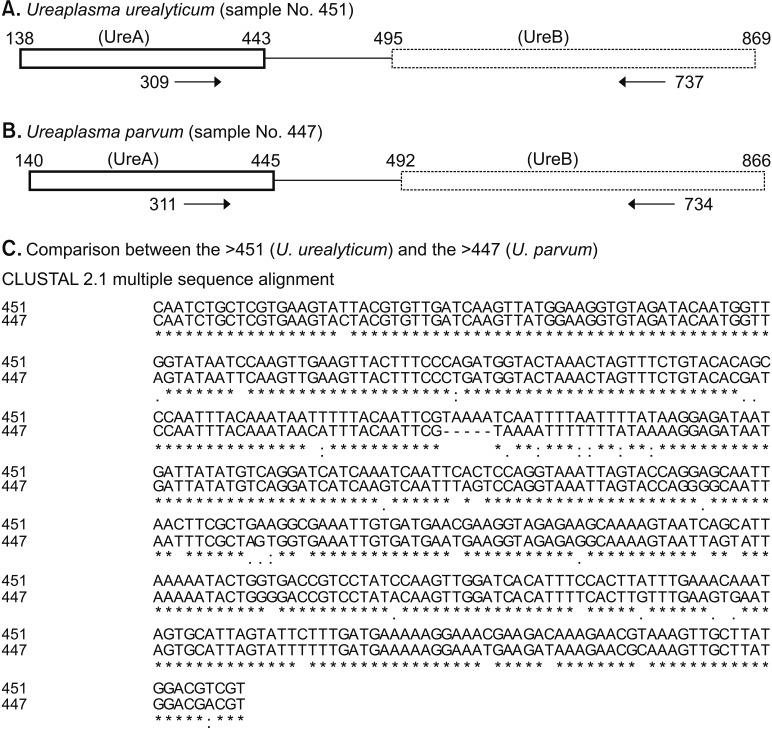

Ureaplasma species are genetically classified into UU and UP. Although conventional researches in genitourinary Ureaplasma infections have been based on NAAT methods, currently there are no Food and Drug Administration-approved clinical tests to differentiate UU from UP infection in the United States. Therefore, sequencing-based Ureaplasma detection and differentiation methods may be employed as a gold standard until properly-evaluated NAATs are established.

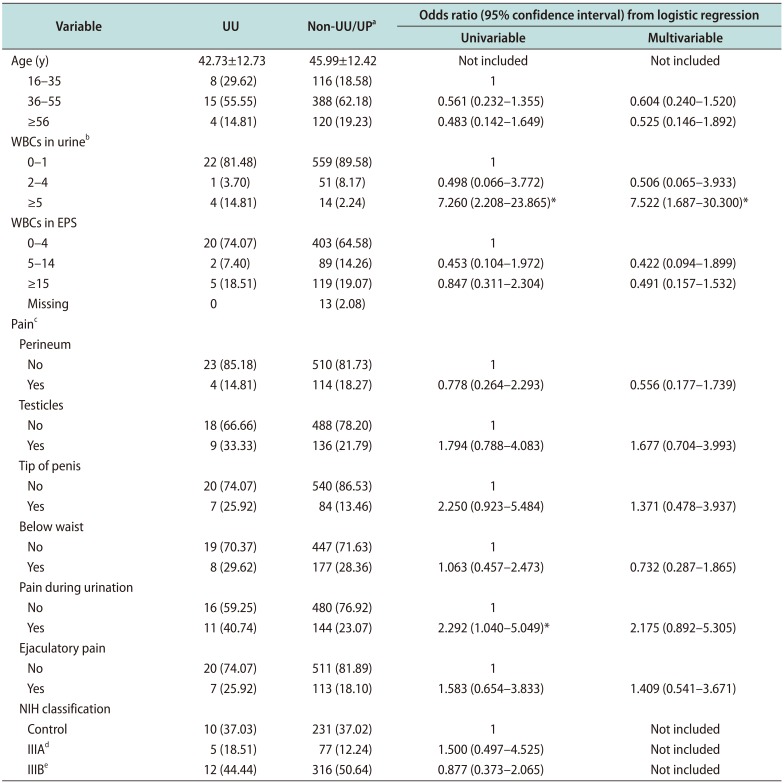

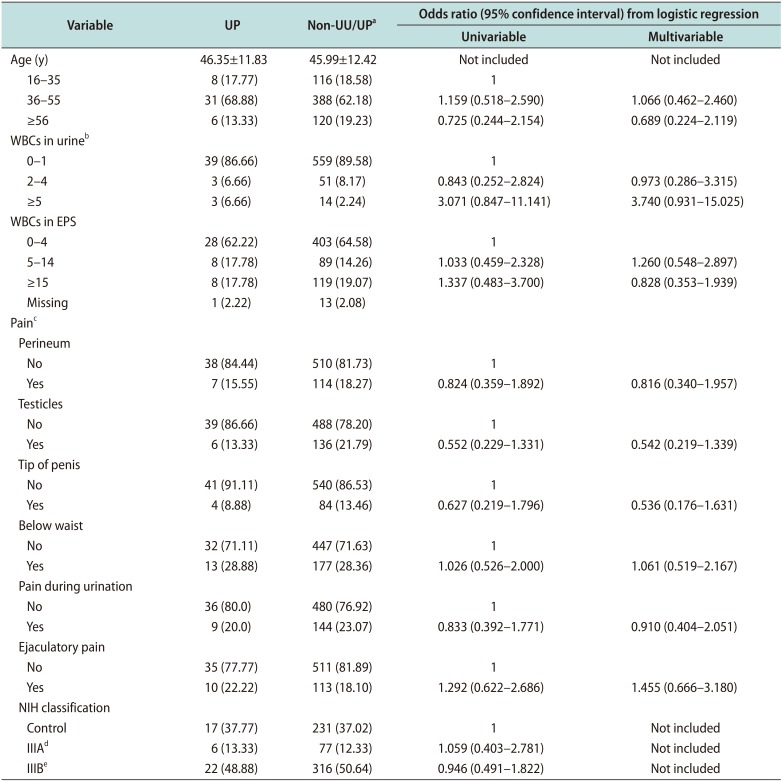

Our results suggest that UU may be associated with NCNG urethritis because UU infections increased the risk of higher WBC counts in urine (≥5 HPF) (adjOR, 7.522; 95% CI, 1.687–30.300). Furthermore, UU infected men had reported more frequently of dysuria or pain during urination than the non-UU/UP group (p=0.035). But, we found that UP was not a pathogen in male urethra. Therefore, UP infections were not justified with antibiotic treatments.

Intracellular incorporating pathogens can also gain a foothold in the genitourinary tract and act as a trigger for chronic inflammation or recurrent epithelial damage, ultimately aggravating chronic genitourinary pain or induce CP [

12]. Prostate can harbor various microorganisms that are not detectable by traditional culture approaches but rather are confirmed by prokaryotic DNA amplification and cloning methods [

420]. With the abilities of

Ureaplasma species to elicit chronic infection in host cell, the possibility of

Ureaplasma species-associated CP has been under debate over the last several decades [

127810].

Although many urologists have been directed to find laboratory biomarkers for CP, we still lack definitive criteria for diagnosis of the disease [

3]. Therefore, patients must be basically evaluated with the NIH-CPSI questionnaire and a lower urinary tract localization test with the Meares–Stamey 4 glass to define CP [

3]. In addition, a proper diagnostic workup for CP must rule out other mimicking conditions, similar to our exclusion criteria. While many STI organisms can contribute to the pathogenesis of CP, typical cases of urethritis must be excluded in CP case-control study. Therefore, we removed the 18 cases of urethral inflammation and re-calculated clinical significances in the remaining 633 cases. Nevertheless, even after adjusting for cases of idiopathic CP, statistical significances between clinical characteristics of CP and the UU infections were not found. The frequencies of each item in the pain domain of NIH-CPSI questionnaire were not different between the adjusted UU infected men

versus non-infected men.

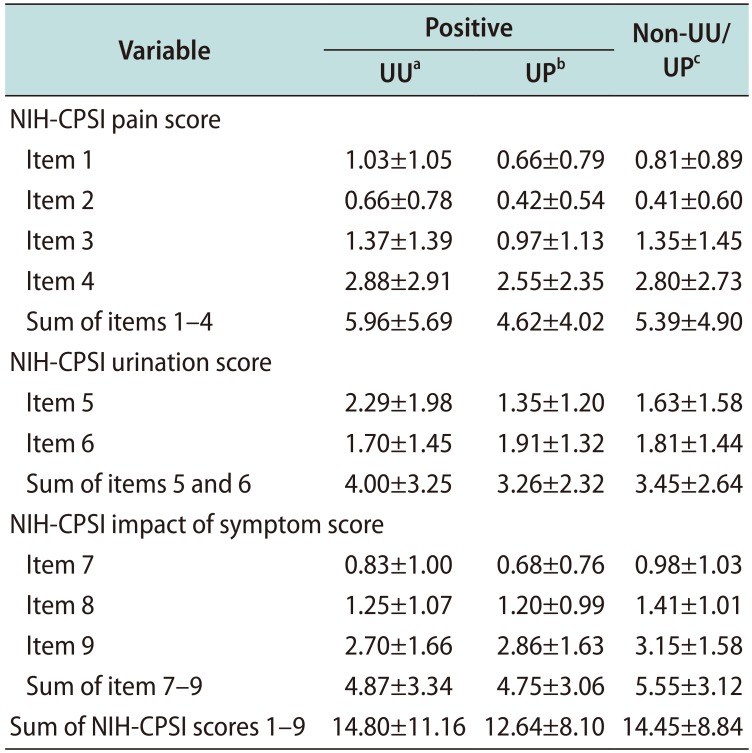

It has been suggested that WBC counting in EPS is the most accurate method in evaluating prostatic inflammation. Therefore, the variations in EPS WBC concentration is a deciding factor for discriminating inflammatory CP from non-inflammatory CP cases. We found that the 4.73% (20/423) of those with WBC counts in their EPS in the range of 0–4 HPF, 2.19% (2/91) in 5–14 HPF group, and 4.03% (5/124) in ≥15 HPF group had UU infections (p=0.549). Even if the effects of urethral inflammation were excluded, the adjusted data analysis revealed the similar results; 4.31% (18/417) of those with WBC counts in EPS in the range of 0–4 HPF, 2.22% (2/90) in the 5–14 HPF, and 2.65% (3/113) in the ≥15 HPF group (p=0.512). Furthermore, we did not observe a significant difference in the response to the NIH-CPSI questionnaire between the UU/UP positive groups

versus the non-UU/UP group. Therefore, we hypothesized that the presence of UU or UP in NAAT from CP patients is not related to the manifestations of CP. Additionally, urinary UU or UP may not be able to invade and trigger inflammation in the prostate because WBC counts in EPS were not statistically different [

35]. Therefore, we advised against antibiotic treatment in UU or UP infections in patients with CP.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download