INTRODUCTION

Drug-induced parkinsonism (DIP) presents with symptoms, such as rigidity, postural instability, and gait disturbance, which also occur in idiopathic Parkinson disease (IPD). Most cases of DIP can be cured by discontinuing the offending drugs, whereas IPD becomes exacerbated over time. However, some DIP patients do not recover completely after discontinuation of the offending drugs.

12 Approximately 20–22% of IPD patients are ultimately diagnosed with DIP.

34 Furthermore, patients taking offending drugs have a 1.9–3.2 times higher possibility of developing Parkinson disease than those who do not.

56 Therefore, to cure DIP and to decrease the risk of IPD, it is very important for doctors to differentiate whether a patient presenting with Parkinsonism is a case of DIP. In patients with DIP, it is necessary to identify which offending drugs the patient uses and to reduce the usage of those drugs to the greatest extent possible.

The most commonly used offending drugs have changed over time. In the past, DIP was commonly reported to be caused by antipsychotics, while today, the common offending drugs are atypical neuroleptics, benzamide derivatives (metoclopramide, levosulpiride, and clebopride), and calcium channel-blocking agents (flunarizine and cinnarizine).

789 There are some differences among countries in the utilization of offending drugs. Some benzamide derivatives, such as levosulpiride, clebopride, and itopride, are not approved for use in the United States or United Kingdom,

1011 although they are prescribed to many people in Korea.

12

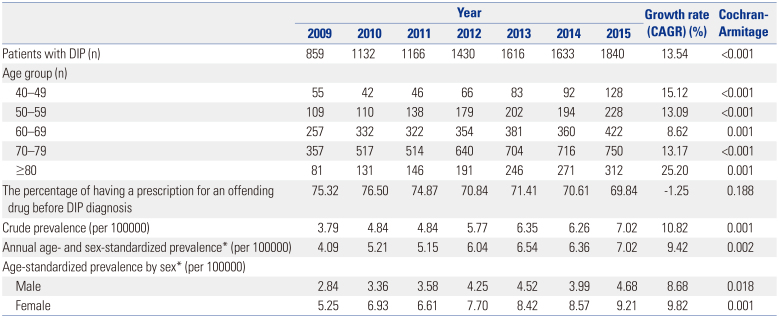

To reduce the occurrence of DIP, the epidemiological characteristics of DIP should be clearly understood. However, little research has investigated the current status of DIP and the use of offending drugs. The aim of this study was to estimate the prevalence of DIP through an analysis of the Korean National Health Insurance Claims (KNHIC) database. Trends in the utilization of offending drugs were investigated in this study as well.

DISCUSSION

This study analyzed the prevalence of DIP from 2009 to 2015 using the NHIS database. DIP is generally characterized by the absence of symptoms of Parkinsonism before the use of an offending drug and by resolution of the symptoms within 6 months of the withdrawal of that drug.

17 To calculate DIP prevalence using a nationwide large-scale database, which is distinct from using patients' medical records, an operational definition of DIP is needed. In this study, when a doctor used a DIP diagnostic code as the principal diagnosis, that patient was defined as having DIP. The problem with this definition is that many patients with DIP may be misdiagnosed with IPD because the clinical features of these two conditions are indistinguishable.

7 In addition, because the NHIS database is a medical utilization record, this does not include people who did not visit medical institutions. As a result, the actual number of DIP patients could have been underestimated.

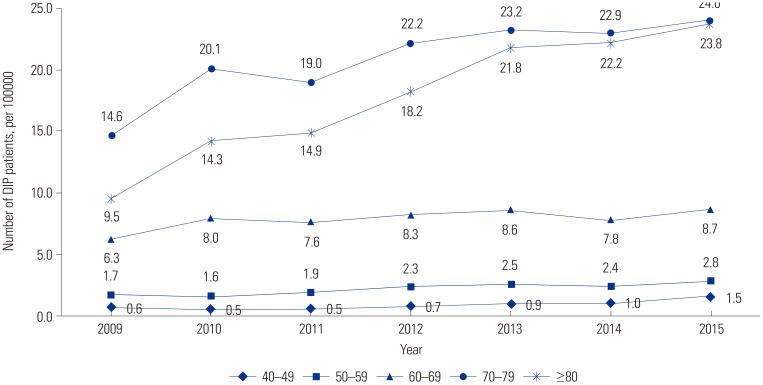

According to the results of this study, there were 7.02 DIP patients per 100000 people aged 40–100 years in 2015. Among those aged 70–79, there were 24.0 patients per 100000 in 2015. Few previous studies have investigated the prevalence of DIP using nationwide administrative data. In one study in Brazil, a prevalence of DIP of 2.7% was estimated using a communitybased survey.

16 In three regions of Spain, a prevalence of 0.49% was calculated using the door-to-door method among older adults.

3418 However, it is difficult to compare these results, since the definition of patients and research methods used were different in each study.

Our study found that DIP was more common in women than in men in all age groups. Female has consistently been reported as a risk factor for DIP.

819 The underlying mechanisms are unknown, and genetic, endocrine, social, and cultural differences may contribute to the higher prevalence of DIP in women. In general, old age is known to be a risk factor for DIP,3 which this study confirmed using large-scale nationwide data. The increasing risk of DIP with age reflects the frequent use of dopamine-blocking agents in recent years for the control of mental disorders with agitation, confusion, delirium, and anxiety.

17

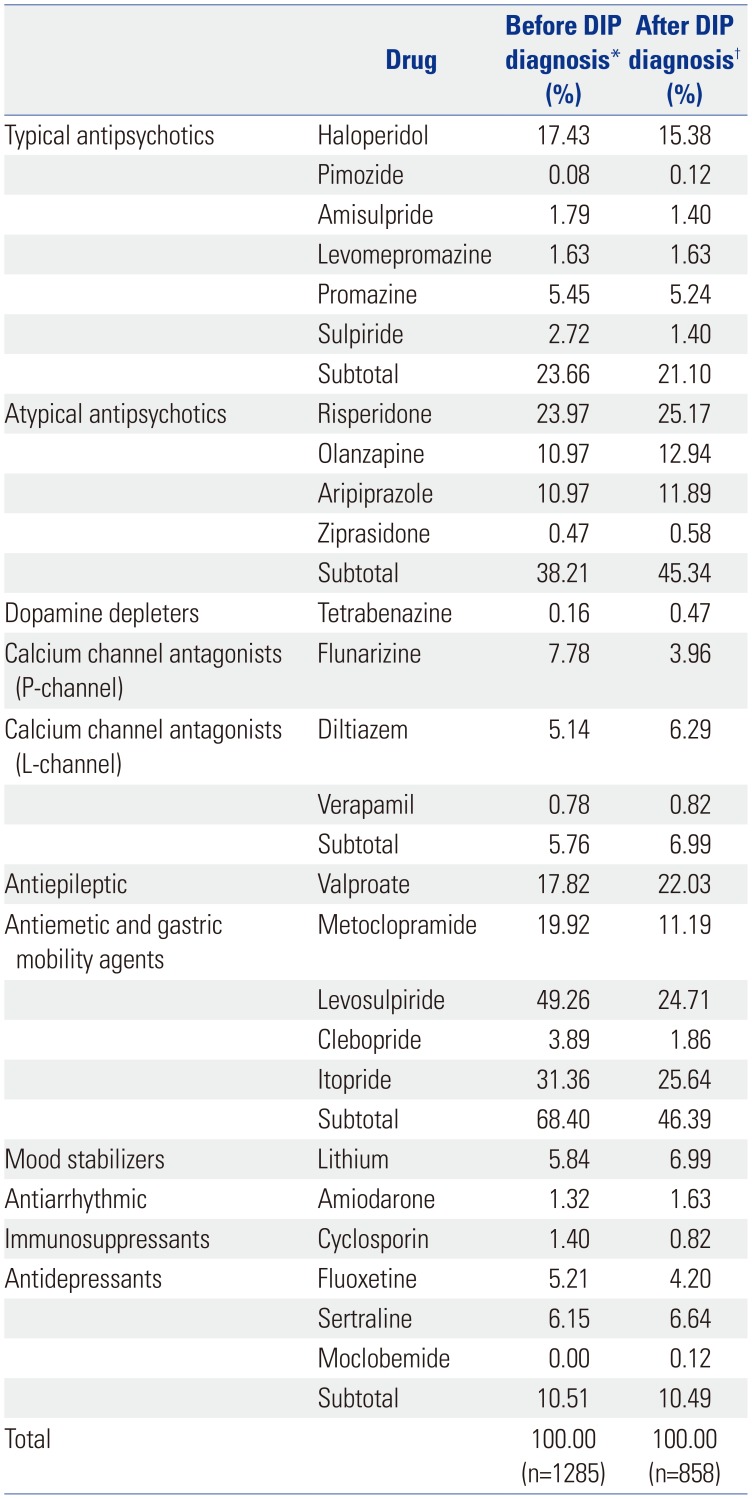

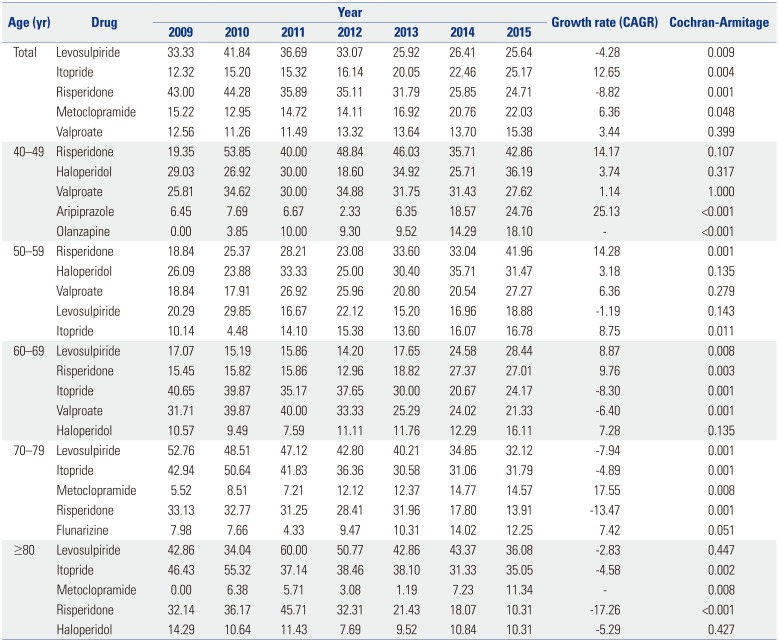

There are no clinical criteria for how long offending drugs must be used to cause DIP symptoms. However, since the length of treatment is a risk factor for DIP, we investigated the types of offending drugs used by DIP patients who had been prescribed them for at least 28 days during the 1-year period prior to the index date.

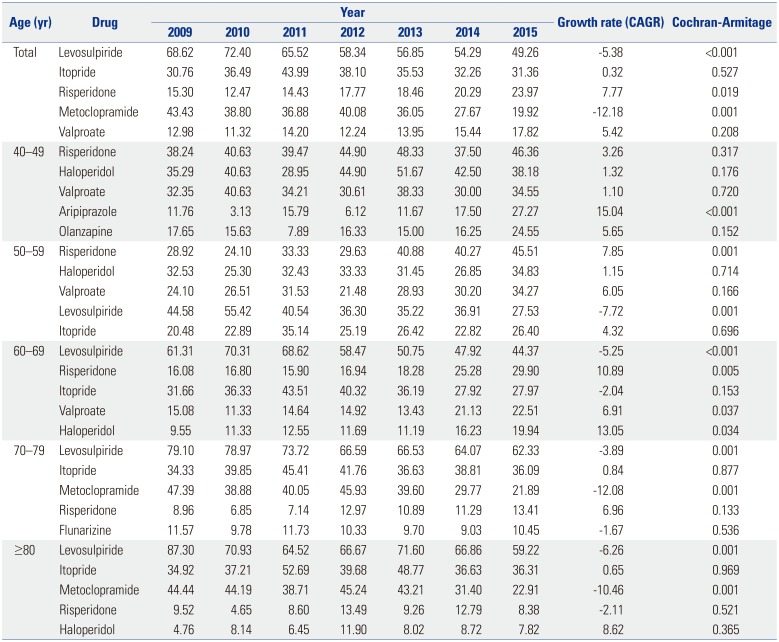

Antiemetic and gastric mobility agents, particularly levosulpiride, were the offending drugs most commonly used by DIP patients. Atypical antipsychotics were the next most frequently used type. Antiemetic and gastric mobility agents, such as levosulpiride, clebopride, and itopride, are not approved in the United States or United Kingdom.

Remarkably, between 2009 and 2015, the usage of levosulpiride drastically decreased while the usage of itopride increased slightly. This downward trend in levosulpiride utilization may have been due to studies reporting the occurrence of DIP caused by levosulpiride,

20212223 which may reflect differences in the ability of levosulpiride and itopride to penetrate the central nervous system.

With respect to therapeutic class, both levosulpiride and itopride are benzamide derivatives, although they have slightly different mechanisms. According to a previous study, levosulpiride has a high affinity (K

i: 27–134 nM) for dopamine 2 receptor antagonism and targets selective dopamine presynaptic auto-receptors in the central nervous system.

24 In contrast, itopride has the same effect in terms of dopamine 2 receptor antagonism, but little effect on the central nervous system.

25 Similarly to other reported results,

26 the time trend of DIP prevalence in all age groups decreased over this recent 7-year period, which may have been related to changes in the usage of prokinetics, including levosulpiride and itopride. Although their CAGRs clearly decreased, these drugs are still frequently and readily prescribed in Korea. Although prokinetics have a low potency for dopamine receptor blocking, they can cause DIP and have also been shown to be associated with cognitive dysfunction.

22

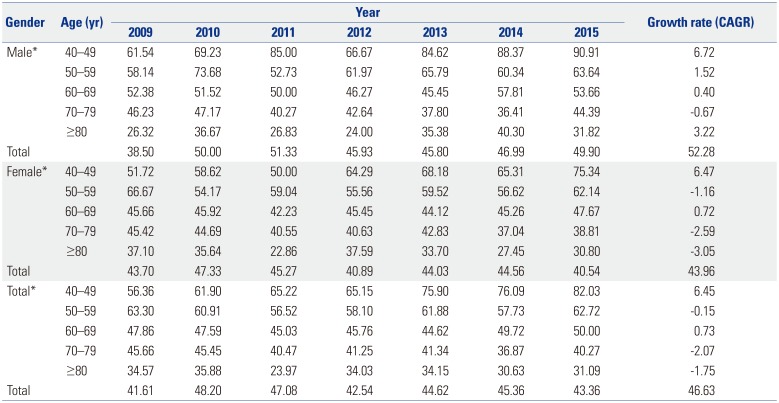

Over 40% of patients continued to use offending drugs after being diagnosed with DIP. In particular, the age group of 40–49 received the most atypical antipsychotic prescriptions for treatment, whereas the age group of 70–79 took the most antiemetic and gastric mobility agents. We believe that physicians regularly prescribe these drugs to treat patients younger than 60 years old. Doctors commonly prescribed benzamide derivatives, such as levosulpiride, itopride, and metoclopramide, in the over-60 group after DIP diagnosis. It is need that physicians pay more attention to prescription patterns in patients who are older than 60.

To prevent and cure DIP, doctors need to reduce the utilization of offending drugs and to find less-risky substitutes. Checking a patient's medication history after the onset of Parkinsonism is also important. In particular, in older adult patients who are at high risk for both DIP and IPD, the long-term use of offending drugs should be considered more carefully and, if necessary, be limited. Additionally, it is necessary to emphasize the need for continuous education on offending drugs.

This is the first representative study to estimate the prevalence of DIP and to identify the usage patterns of offending drugs among the Korean population. Despite these contributions, our study has several limitations. First, we used prescription claims data, so we could not identify whether patients actually took the prescribed medicines. Second, the diagnosis of DIP was determined in this study using an operational definition. Since some doctors may not have recognized DIP in their patients, some patients might have not been included in this study.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download