Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this cross-sectional, correlational study was to identify associations of acculturative stress, depression, and quality of life among Indonesian migrant workers living in South Korea.

Methods

A total of 91 migrant workers who were recruited in Korea completed paper-and-pencil self-administered questionnaire in September 2018. Acculturative Stress Scale, Patient Health Questionnaire-9, World Health Organization Quality of Life Instrument, Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), Perceived Organizational Support Scale, and demographic questionnaire were used to measure acculturative stress, depression, quality of life, social support, and organizational support, respectively. We applied descriptive statistics, Pearson's correlation coefficients, and multiple linear regression analyses with SPSS 22 program.

Results

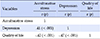

A positive correlation was shown between acculturative stress and depression and a negative correlation was found between acculturative stress and quality of life. Significant factor associated with depression was acculturative stress. Significant factors associated with quality of life were acculturative stress and social support.

Recently, a number of migrants travel around the world to make their home in another country. The South Korean government's office of statistics has stated that the number of foreign migrant workers in South Korea reached 962,000 in 2016 and it has increased year by year since 2012 [1]. One of motivations for migration is to look for better job opportunities. Unfortunately, everyone does not go through acculturation smoothly [2] because they fail to adapt an unfamiliar society with different culture barriers and challenges. The term ‘acculturation’ is defined as the phenomenon that different cultures result in certain replacements in the original tradition of one or both groups [3]. According to the acculturation theory [3], some people have to deal with acculturative stress during this complex process. Acculturative stress occurs when individuals try to adjust to a new culture and integrate the new and unfamiliar ethnic characteristics of their host society with their own cultural characteristics [4].

This acculturative stress affects mental health issues, such as anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, higher occurence of somatic symptoms and even suicide [5]. Particularly, depression is associated with the low quality of life of migrant workers, that has been linked to decreasing work performance and untimely retirement [6]. The process of acculturation is also influenced by individual and environmental factors including social support and organizational support. Social support shows diverse forms of support and helps existed among relationship with families, friends, and neighbors [7]. Organizational support is reflected by organization's behavior toward their workers based on workers' behaviors and point of views toward their organization [8]. Therefore, acculturative stress of migrant workers can lead to depression, which affects their quality of life along with individual and environmental factors, such as social support and organizational support.

Annually, many Indonesians travel to South Korea and at least 90% of native Indonesians who stay in South Korea are migrant workers. In South Korea, Indonesian community is well-known as the second largest community among other Muslim communities and the number continously increases [9]. Islam influences how most Indonesians live their daily lives, such as strict rules on eating, lifestyle, praying routines, and wearing hijab. As a result, compared to other immigrants from Confucian or Buddhist countries who share a common cultural tradition with Korea, Indonesians are more likely to encounter unique challenges when adjusting to Korean society. Regardless of the increasing number of Indonesians living in Korea and unique challenges that they face, acculturative stress, depression, and quality of life among them have not been studied. The majority of existing studies on acculturative stress and mental health have focused on Vietnamese and Korean-Chinese migrants [210].

Indonesian migrant workers are reported to lack Korean language skill and some of them have experienced human rights violations, such as physical or verbal abuse, received low wages, faced discrimination, and brutal working conditions. Some of them respond to these negative experiences and overcome stress by isolating themselves from the Korean community and are more likely to spend time with people from Indonesia in their own community [9]. Consequently, they may experience an increased risk of mental health problems. Thus, it is important to explore the level of acculturative stress experienced by this unique group and identify associations of depression, quality of life, and other related factors with Indonesian migrant workers' acculturative stress.

This study used cross-sectional, correlational study design to identify the associations among acculturative stress, depression, and quality of life in Indonesian migrant workers living in South Korea.

This study participants were migrant Indonesian workers who currently worked in South Korea. Only migrant workers who were 20 to 65 years old and able to read and understand Indonesian were invited to participate in the study. This study used non-probability sampling methods, namely convenience and snowball sampling. The significance level used for this study is an α level of .05 and the power of .80 is used. Based on a previous study [11], a medium effect size (r) of 0.3 was selected for this study. Based on the significance level, effect size, and power, the sample size for this study was calculated by using the G* Power program and the minimum sample size required was 82. Taking into account that 20% of dropout rate, required sample size was 98. For this study, among the 120 migrant workers who were approached by the researcher, 98 workers agreed to participate in this study (response rate 81.7%). A total of 91 questionnaires were included for final analysis after excluding 7 incomplete questionnaires.

All of the measurements used in this study were Indonesian to minimize language barrier.

Acculturative stress was measured using the Acculturative Stress Scale developed by Sandhu and Asrabadi [12]. The original version of this scale includes 36 items with 7 subscales: perceived discrimination (7 items), homesickness (4 items), perceived hate (5 items), fear (4 items), stress due to change/culture shock (3 items), guilt (2 items), and nonspecific concerns (10 items). Each question in this questionnaire was rated based on a 5-point Likert scale, from ‘strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘strongly agree’ (5) with (3) as ‘not sure’. The total scores range from 36 to 180, that the higher score indicates the higher level of acculturative stress.

The Indonesian version of this scale was developed by the investigator through the systematic translation process, including translation, back translation, and cognitive interviews. The Cronbach's α from previous study was .95 [13] and .94 for this study.

Depression was measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) developed by Kroenke, Spitzer, and Williams in 2001 [14]. The original version of this scale includes 9 items. Each question in this questionnaire was rated using a 4-point Likert scale, from not at all (0) to nearly every day (3). The total scores range from 0 to 27 with five severity categories: minimal (0~4), mild (5~9), moderate (10~14), moderately severe (15~19), and severe (20~27). The Cronbach's α from previous study was .89 [14] and .84 for the present study.

Quality of life of migrant workers was measured using the World Health Organization Quality of Life Instrument (WHOQOL-BREF) developed by the World Health Organization [15]. The WHQOL-BREF includes 26 questions with four domains: physical health, psychological, social relationships, and environment. WHOQOL-BREF uses a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 indicates the worst quality of life and 5 indicates the best quality of life. The total scores range from 26 to 130. From the previous study, the Cronbach's α was above .70 for all domains, except for social relationship domain (.41). Low Cronbach's α for social domain is possibly due to fewer number of items than other domains [16]. The Cronbach's α for the present study was .90.

Individual factors measured in this study included age, sex, occupation, living area, educational background, monthly wages, working hours per day and per week, Korean language proficiency, and the length of stay in South Korea.

Social support was measured using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) [17]. MSPSS has been used to measure perceived social support among people from various cultures and also students living in foreign country. This scale contains 12 items with three subscales: family, friends, and significant others. Each subscale is represented by four questions. The original version of MSPSS uses a 7-point Likert scale. But considering the nature of Indonesian's characteristics, in that they tend to pick a “neutral” choice, the Indonesian version of MSPSS was changed to a 6-point Likert scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (6). The total scores range from 12 to 72 with 2 categories: <56 (low) and ≥56 (high). These categories were divided using the formula: X < Median as the low category and X ≥Median as the high category. The Cronbach's α from the previous study was .76 [18] and .91 for the present study.

Organizational support was measured using Indonesian version of the Perceived Organizational Support scale (POS) [19], originally developed by Eisenberger and the collegues [20]. The POS scale originally has 36 items with a 7-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). However, the POS Indonesian version has a 4-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4) [19]. The total scores range from 36 to 144 with 3 categories: <89 (low), 89~107 (middle), and >107 (high). The Cronbach's α from previous study was .97 [20] and .86 for the present study.

The Indonesian version of the Acculturative Stress Scale was developed through a series of steps: translation of the English version of the Acculturative Stress Scale by the researcher who is fluent in both English and Indonesian and cognitive interviews with four native Indonesian adults and three nursing students. The reliability and validity of the Indonesian version of the Acculturative Stress Scale were tested in SPSS. The Acculturative Stress Scale Indonesian version exhibited an excellent reliabilty (α=.94) based on Cronbach's α test. All correlations between the constructs were statistically significant (p<.001) and it showed that Acculturative Stress Scale Indonesian version exhibited good construct validity through Pearson's correlation coefficients.

After obtaining an approval from the Institutional of Review Board of the affiliated university (IRB number 1808/001-003), data collection was performed in September 2018. The researcher visited mosques, Indonesian restaurants, and gathering places to recruit eligible participants using recruitment flyers. No announcement was made at migrants' places of work in order to protect migrant workers' freedom from their employer. There was no consideration to oversampling depending on different sex groups.

When eligible participants expressed interest in participating in the study, the researcher provided them further information about the study. Once the eligible participants had agreed to join the study and signed the informed consent, they were given paper-and-pencil self-administered questionnaire. In private places, the participants were instructed to complete the questionnaires based on their experiences while living in South Korea as migrant workers. They were informed that they have right to withdraw from participation at any time. The questionnaires contained five sections (acculturative stress, depression, quality of life, social support, and organizational support) with a total of 119 questions. It took about 20 to 30 minutes for participants to complete the questionnaire. To protect the confidentiality and anonymity of the participants, every participant was given an ID number and data was stored on the researcher's personal PC protected by a password and accessible only to the researcher.

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) software program, version 22. Before conducting the main analysis, multicollinearity of independent variables was examined. The obtained variance inflation factor value was less than 2.00, indicating that there was no multicollinearity. The demographic characteristics of the study sample included age, sex, occupation, living area, educational background, monthly wages, working hours per day and per week, Korean language proficiency, and the length of stay in South Korea. The acculturative stress score, depression score (PHQ-9), quality of life score (WHOQOL-BREF), social support score (MSPSS), and organizational support (POS) were summarized using descriptive statistics. The psychometric properties of all instruments were also examined. Associations among acculturative stress, depression, and quality of life were analyzed using Pearson's correlation coefficients. To identify significant factors associated with depression and quality of life, multiple linear regression analyses were performed. The Durbin-Watson value of significant factors for depression was 1.99 and showed that there was a positive autocorrelation. The Durbin-Watson value of significant factors for quality of life was 2.12 and this demonstrated a negative autocorrelation.

The demographic characteristics of the paticipants are shown in Table 1. Participants ranging in age between 20 and 24 were the most commonly represented (51.6%). The participants were mostly male (76.9%), worked as factory workers (94.5%), lived outside Seoul, graduated from high school in terms of their highest educational backgound (90.1%), and received wages of 1~2 million won per month (92.3%). Indonesian migrant workers commonly work for less than 8 hours per day (49.4%) and accumulately 40~49 hours per week (51.6%). Most Indonesian migrant workers who work in South Korea (76.9%) were able to communicate in Korean. In terms of the length of stay, the participants generally have stayed in South Korea for 1~2 years (40.6%).

The mean score for the Acculturative Stress Scale was 86.37 (SD=19.67). The mean score for the depression scale was 5.16 (SD=4.39). Meanwhile, the mean score for quality of life was 89.85 (SD=11.20).

A significant positive correlation was shown between acculturative stress and depression (r=.41, p<.001). Meanwhile, a significant negative correlation was found between acculturative stress and quality of life (r=−.42, p<.001). A significant negative correlation was also found between depression and quality of life (r=−.47, p<.001).

At first, a multiple linear regression analysis was carried out to identify significant factors that associated with depression. The occupation variable was excluded from this analysis because most of the study participants were factory workers. The working hours per day variable was also excluded because it was highly correlated with the working hours per week variable. The multiple regression analysis showed that those variables explained 0.17 of the variance in depression. Acculturative stress was the only significant variable that associated with depression (p<.001).

Another multiple linear regression analysis was carried out to identify factors associated with quality of life. The variables occupation and working hours per day were also excluded from this analysis. Those variables were found to explain 0.4 of the variance in the level of quality of life. Social support and acculturative stress were the significant variables associated with quality of life (p<.001).

This cross-sectional, correlational study was conducted to identify associations among acculturative stress, depression, and quality of life in 91 Indonesian migrant workers living in South Korea. The mean of individual item scores for acculturative stress was 2.4 and this score was higher than the scores reported by Thai (mean score=2.3), Vietnamese (mean score=2.1) and Filipino (mean score=2.2) female migrant workers living in South Korea. Relatively high level of acculturative stress reported by Indonesian migrant workers are possibly due to the distinct differences in cultural and religious characteristics between Korea and Indonesia [21].

The mean of individual item scores for depression among Indonesian migrant workers in the present study was 5.16 indicating that Indonesian migrant workers had mild depression. The score was higher than that for Mexican migrant workers living in the United States [22]. The mean scores from the prior study assessing depression among Mexican migrant workers was 4.26 for indigenous Mexican migrants and 3.63 for non-indigenous or mestizo Mexican migrants.

The mean score for quality of life among the study participants was 89.85 (SD=11.21). This is higher than the score reported from a previous study on new-generation migrant workers in Eastern China (mean score=62.8) [23]. Thus, Indonesian migrant workers in South Korea are considered to have a higher level of quality of life compared to migrant workers in Eastern China. The quality of life score for the present study is also higher than that of the previous study that explored the factors influencing the quality of life among foreign migrant workers from diverse countries in South Korea (mean score=71.3) [24]. Namely, regardless of high level of acculturative stress, Indonesian migrant workers had mild level of depression and still managed to maintain high quality of life. Due to the dearth of studies on acculturative stress, depression, and quality of life among Indonesian migrant workers, it is difficult to provide clear explanations for the phenomenon. One of the possible reasons is the power of religious belief that plays important function in Indonesian's life. Such beliefs may help them to go through any hardships and accept God's will. Another possible reason for the finding is the high wages that South Korea offers to Indonesian migrant workers.

The present study demonstrated the significant associations between acculturative stress, depression, and quality of life among Indonesian migrant workers. Particularly, acculturative stress was found to be a significant factor associated with depression. The finding is consistent with a previous study that demonstrated the significant impact of acculturative stress on the level of depression among Vietnamese immigrant women in South Korea [10]. High level of acculturative stress was associated with high level of depression and low level of quality of life and it negatively affected psychological aspects of an individual's well-being [25]. Considering the significant associations among acculturative stress, depression, and quality of life, it would be important to continue to pay attention to depression and quality of life among Indonesian migrant workers. In this study, individual factors were not significantly associated with depression nor quality of life among Indonesian migrant workers. These insignificant findings were possibly due to the homogeneity of the sample. Most of the Indonesian migrant workers were male, had worked in factories outside Seoul for 1 to 2 years, and had a similar amount of wages per month.

In the present study, social support was a significant factor associated with quality of life. Xing et al. [23] assessed the level of social support using WHOQOL-BREF and the Social Support Rating Scale and found that social support affected quality of life among migrant workers in Eastern China. The researchers assumed that social support of people from an individual's country of origin could be limited in urban areas because of unfriendliness and neighbourhood characteristics. For Indonesian migrant workers, living in Ansan might feel less stressful compared to living in Seoul because of a number of Indonesian people living in Ansan shared the same experience as migrant workers. In the previous study with a diverse group of migrant workers in Korea, living area was found to be one of the factors influencing migrant workers' quality of life [24]. Social support has a positive impact on an individual, in terms of feelings of self-worth, sense of security about life situation, and avoiding negative experiences [26]. Indonesian migrant workers had regular gatherings and spiritual meetings and this may contribute to increasing social support. When an individual has a low level of stress and strong ties with people, and feels involved and part of a group, their quality of life is improved [27].

In this study, organizational support was not a significant factor for quality of life. Although the result for this study was not significant, an individual's employing organization or work environment is considered to play a significant role in improving their quality of life, job satisfaction, and stability in social and work life among migrant workers. In addition, self-esteem could be enhanced by receiving organizational support which provides guidance and opportunities to meet an individual's socio-emotional needs in terms of reward and self-efficacy [28]. The feeling of being supported by an organization may help migrant workers to experience low level of stress [29]. Future studies investigating the role of organization support on mental health and quality of life among migrant workers are needed.

There were some limitations in the present study. Indonesian migrant workers who participated in this study were mostly male, factory workers, living in Ansan (outside Seoul), and most had stayed in South Korea for approximately 1~2 years. These homogenous characteristics made it difficult to generalize our findings. Another limitation was the cross-sectional nature of the study which cannot provide a clear explanation of direction for the causual relationship among the variables.

For future research, a qualitative study aiming to provide an in-depth understanding of acculturation experiences among Indonesian migrant workers is needed. Based on the results, interventions designed to lower acculturative stress and promote mental health could be developed. Migrants encounter diverse barriers to using mainstream mental health services due to language differences and perceived stigma, thus it is important to educate them about the importance of early detection and timely mental heath treatment.

This study was a cross-sectional, correlational study which was designed to identify associations of acculturative stress, depression, and quality of life among Indonesian migrant workers living in South Korea. A significant positive correlation was found between acculturative stress and depression and a negative correlation was found between acculturative stress and quality of life. Acculturative stress was found to be a significant factor associated with depression. Significant factors associated with quality of life were acculturative stress and social support. The present study provide fundamental information for Indonesian migrant workers in South Korea and laid the cornerstone for the future study with the population.

Figures and Tables

Notes

References

1. Hankyoreh. Number of foreign workers in South Korea nearing 1 million [internet]. 2016. cited 2018 Oct 11. Available from: http://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_international/766834.html.

2. Jeon HJ, Lee GE. Acculturative stress and depression of Vietnamese immigrant workers in Korea. Journal of Korean Academy of Community Health Nursing. 2015; 26(4):380–389. DOI: 10.12799/jkachn.2015.26.4.380.

3. Berry JW. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 1997; 46(1):5–68. DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01087.x.

4. Samuel E. Acculturative stress: South Asian immigrant women's experiences in Canada's Atlantic provinces. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies. 2009; 7(1):16–34. DOI: 10.1080/15562940802687207.

5. Sirin SR, Ryce P, Gupta T, Rogers-Sirin L. The role of acculturative stress on mental health symptoms for immigrant adolescents: a longitudinal investigation. Developmental Psychology. 2013; 49(4):736–748. DOI: 10.1037/a0028398.

6. Zhu CY, Wang JJ, Fu XH, Zhou ZH, Zhao J, Wang CX. Correlates of quality of life in China rural-urban female migrate workers. Quality of Life Research. 2012; 21(3):495–503. DOI: 10.1007/s11136-011-9950-3.

7. Joo HC, Kim JY, Cho SJ, Kwon HH. The relationship among social support, acculturation stress, and depression of Chinese multi-cultural families in leisure participations. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2015; 205:201–210. DOI: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.09.059.

8. Amazue LO, Onyishi IE. Stress coping strategies, perceived organizational support and marital status as predictors of worklife balance among Nigerian bank employees. Social Indicators Research. 2016; 128(1):147–159. DOI: 10.1007/s11205-015-1023-5.

9. Yun M, Kim E. An ethnographic study on the Indonesian immigrant community and its Islamic radicalization in South Korea. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. 2019; 42(3):292–313. DOI: 10.1080/1057610X.2017.1374672.

10. Chae SM, Park JW, Kang HS. Relationships of acculturative stress, depression, and social support to health-related quality of life in Vietnamese immigrant women in South Korea. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2014; 25(2):137–144. DOI: 10.1177/1043659613515714.

11. Kim JY. Uncertainty, social support, posttraumatic stress symptoms and psychological growth in patients with hematologic cancers [master's thesis]. Seoul: Seoul National University;2015. 90.

12. Sandhu DS, Asrabadi BR. Development of an Acculturative Stress Scale for international students: preliminary findings. Psychological Reports. 1994; 75(1):435–448. DOI: 10.2466/pr0.1994.75.1.435.

13. Lee H, Ahn H, Miller A, Park CG, Kim SJ. Acculturative stress, work-related psychosocial factors and depression in Korean-Chinese migrant workers in Korea. Journal of Occupational Health. 2012; 54(3):206–214. DOI: 10.1539/joh.11-0206-OA.

14. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001; 16(9):606–613. DOI: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x.

15. World Health Organization (WHO). The World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL)-BREF [internet]. 2004. cited 2018 Apr 1. Available from: https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/en/indonesian_whoqol.pdf.

16. Salim OC, Sudharma NI, Kusumaratna RK, Hidayat A. Validitas dan reliabilitas World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF untuk mengukur kualitas hidup lanjut usia. Universa Medicina. 2007; 26(1):27–38.

17. Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1988; 52(1):30–41.

18. Aprianti I. The correlation between perceived social support and psychological well-being among first-year migrant students at Universitas Indonesia [Bachelor]. Indonesia: Universitas Indonesia;2012. 74.

19. Nurmala K. Perceived Organizational Support (POS), Keadilan Organisasi, dan self-monitoring sebagai prediktor organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) [Bachelor]. Indonesia: Universitas Islam Negeri Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta;2015. 218.

20. Eisenberger R, Huntington R, Hutchison S, Sowa D. Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1986; 71(3):500–507. DOI: 10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500.

21. Lee H, Ahn H, Park CG, Kim SJ, Moon SH. Psychosocial factors and work-related musculoskeletal disorders among Southeastern Asian female workers living in Korea. Safety and Health at Work. 2011; 2(2):183–193. DOI: 10.5491/SHAW.2011.2.2.183.

22. Donlan W, Lee J. Indigenous and Mestizo Mexicant migrant farmworkers: a comparative mental health analysis. Social Work Faculty Publications and Presentations. 2010; 83.

23. Xing H, Yu W, Chen S, Zhang D, Tan R. Influence of social support on health-related quality of life in new-generation migrant workers in Eastern China. Iranian Journal of Public Health. 2013; 42(8):806–812.

24. Lee E, Lee JM. Quality of life and health service utilization of the migrant workers in Korea. Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial cooperation Society. 2014; 15(7):4370–4379. DOI: 10.5762/KAIS.2014.15.7.4370.

25. Oh JH. Relationships between acculturative stress, depression, and quality of life on in North Korean refugees living in South Korea. Journal of Health Education Research and Development. 2015; 3(3):1–8. DOI: 10.4172/2380-5439.1000142.

26. Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985; 98(2):310–357.

27. Helgeson VS. Social support and quality of life. Quality of Life Research. 2003; 12(1):25–31.

28. Kurtessis JN, Eisenberger R, Ford MT, Buffardi LC, Stewart KA, Adis CS. Perceived organizational support: a meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support. Journal of Management. 2017; 43(6):1854–1884. DOI: 10.1177/0149206315575554.

29. Ahmed I, Wan Ismail WK, Mohamad Amin S, Ramzan M. Conceptualizing perceived organizational support: a theoretical perspective. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences. 2011; 5(12):784–789.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download