Journal List > Dement Neurocogn Disord > v.18(2) > 1128675

Nonketotic hyperglycemia, a metabolic disorder, can present with various neurological symptoms including relatively common seizures, which present as focal hyperperfusions by single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), comprise electroencephalography (EEG) that include epileptic discharges, and tend to quickly resolve with conservative treatment including blood glucose management.12 Most seizures in nonketotic hyperglycemia are motor seizures, whereas aphasic seizures with no changes in consciousness are less frequent.3 We herein report a patient with persistent hyperglycemia-induced aphasia who recovered gradually despite effective blood glucose management.

A 48-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with language impairment for 1 week. He responded to questions with irrelevant answers. He could not understand long questions immediately, appeared to think for a long time, and stated that he did not understand the question. He also preferred short questions that were presented slowly. He could express himself using short and simple statements and could read short statements.

His medical history was unremarkable, and his vital signs at the time of admission were stable. During neurological examination, his level of consciousness was unaltered. He showed signs of mixed aphasia, with comparatively preserved ability to verbally repeat statements despite reductions in fluency and comprehension during language function assessment; repeating was comparatively preserved. Cranial nerve examination, motor and sensory tests, and pathological reflexes were normal. There were no structural or vascular abnormalities by magnetic resonance imaging in whole brain as well as motor speech area. Although he had no known underlying illnesses, his blood glucose and glycated hemoglobin were 518 mg/dL and 11.9%, respectively, at the time of admission, indicating hyperglycemia and diabetes. The patient was initiated on treatment with multiple insulin injection therapy.

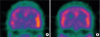

EEG on the second day of hospitalization revealed diffuse slow waves without epileptic discharges (Fig. 1A). The follow-up EEG on the sixth day of hospitalization showed slow waves in the frontal lobe; however, no abnormalities were observed in the two-day video EEG monitoring conducted from the ninth to the tenth day of hospitalization although aphasia symptom existed (Fig. 1B). Brain perfusion SPECT on the third day showed hyperperfusion in the left lateral temporal cortex (Fig. 2A). The patient's language was assessed using the Screening Test for Aphasia and Neurologic Communication Disorder (STAND) comprising six subtests: figure description (3 points), naming (4 points), comprehension (10 points), repetition (3 points), reading (7 points), and writing (3 points). The total STAND score was 25/30 points, with the following subscores: figure description (2/3 points), naming (2/4 points), comprehension (8/10 points), repetition (3/3 points), reading (7/7 points), and writing (3/3 points). The patient was slow in answering the interviewer's questions and requested the repetition of questions multiple times.

Blood glucose management over a week of hospitalization led to the gradual recovery of fluency and comprehension. The total STAND score on the eighth day of hospitalization was 29/30 points, with the only point deducted for naming. The patient was discharged with recovery.

The outpatient follow-up evaluation performed 1 month after the symptom onset demonstrated that the patient recovered to presymptomatic levels without evidence of aphasia. The glycated hemoglobin level was decreased to 8.9%, and the previously observed hyperperfusion in the left lateral temporal cortex by brain perfusion SPECT had disappeared (Fig. 2B).

Altered consciousness, convulsions, and dyskinesia are commonly reported in nonketotic hyperglycemia, which can present with various neurological symptoms (4). Aphasia was the primary symptom in the current case. Despite no epileptic discharges on EEG, hyperperfusion, which is common during convulsions, was observed in the left lateral temporal cortex by brain perfusion SPECT.

Hyperglycemia-induced metabolic encephalopathy requires supportive treatment including fluid replacement and blood glucose management, and recovery time from accompanying neurological symptoms varies.4 Hyperglycemia-induced chorea was reported to continue anywhere from two weeks to several months.5 The current patient gradually recovered from aphasia during hospitalization, albeit at a relatively slow pace, and was discharged without complete recovery despite eight days of hospitalized treatment. His clinical course is in line with the previously reported cases of hyperglycemic aphasia in which recovery took from 4 to 11 days of hospitalization.1367

Similar to previous cases of aphasic seizures, hyperperfusion of the left lateral temporal cortex, commonly observed during seizures, was found by SPECT.89 However, the recovery was gradual rather than immediate despite appropriate blood glucose management in this case, and epileptic discharges were not observed on EEG. Altogether, these findings indicate that a minimal risk of epileptic seizures or status epilepticus.

The patient was not aware of his diabetes; thus, we could not accurately ascertain the duration of hyperglycemia. Moreover, we used the STAND and not the Korean version of the Western Aphasia Battery to assess the impairment of language, which was another limitation. Furthermore, EEG and SPECT were performed one day apart; thus, it remains possible that the inconsistency between the two tests might be due to the difference in times of assessment. However, the patient had persistent clinical signs of aphasia and later underwent multiple EEG sessions, including video EEG monitoring, which allowed us to examine the differences between the clinical signs and the test results.

This was a case of hyperglycemia-induced metabolic encephalopathy presenting as aphasia without evidence of accompanying seizures. While previous cases focused on aphasic seizures based on SPECT and EEG findings, the current case illustrates the possibility that changes in SPECT images over time might be a sign of epilepsy in metabolic encephalopathy. So, underlying mechanism of our patients might be due to aphasic status without evidence of EEG or metabolic encephalopathy with slow recovery due to delayed treatment of hyperglycemia. Generally, treatment of the etiology underlying metabolic encephalopathy including hyperglycemia is anticipated to result in a quick recovery of neurological symptoms. However, the symptoms may persist even with appropriate treatment in hyperglycemia-induce chorea. The gradual rather than immediate and imminent recovery of symptoms despite blood glucose management in the current patient compared with the previously reported patients with aphasic seizures suggest that the timing of treatment for symptomatic recovery in metabolic encephalopathy might vary.

1. Tetsuka S, Yasukawa N, Tagawa A, Ogawa T, Otsuka M, Hashimoto R, et al. Isolated aphasic status epilepticus as a manifestation induced by hyperglycemia without ketosis. J Neurol Res. 2016; 6:85–88.

2. Ergün EL, Saygi S, Yalnizoglu D, Oguz KK, Erbas B. SPECT-PET in epilepsy and clinical approach in evaluation. Semin Nucl Med. 2016; 46:294–307.

3. Kim J, Lee S, Lee JJ, Kim BK, Kwon O, Park JM, et al. Aphasic seizure as a manifestation of non-ketotic hyperglycemia. J Korean Neurol Assoc. 2012; 30:309–311.

5. Cosentino C, Torres L, Nuñez Y, Suarez R, Velez M, Flores M. Hemichorea/hemiballism associated with hyperglycemia: report of 20 cases. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y). 2016; 6:402.

6. Lee JH, Kim YA, Moon JH, Min SH, Song YS, Choi SH. Expressive aphasia as the manifestation of hyperglycemic crisis in type 2 diabetes. Korean J Intern Med. 2016; 31:1187–1190.

7. Huang LC, Ruge D, Tsai CL, Wu MN, Hsu CY, Lai CL, et al. Isolated aphasic status epilepticus as initial presentation of nonketotic hyperglycemia. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2014; 45:126–128.

8. Kim HY, Shon YM, Seo DW, Na DL. A case of aphasic status with brain 99m-tc ethyl cysteinate diethylester single photon emission computed tomography demonstrating focal hyperperfusion. J Korean Neurol Assoc. 2000; 18:333–336.

- TOOLS

- ORCID iDs

-

Chungkun Oh

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6482-3810Seo-Young Lee

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5319-1777Jae-Won Jang

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3540-530X - Similar articles

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download