Abstract

Background

Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) has the potential to serve as a non-invasive prognostic biomarker in some types of neoplasia. The investigation of plasma concentration of cfDNA may reveal its use as a valuable biomarker for risk stratification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). The present prognostic value of plasma cfDNA has not been widely confirmed in DLBCL subjects. Here, we evaluated cfDNA plasma concentration and assessed its potential prognostic value as an early DLBCL diagnostic tool.

Methods

cfDNA concentrations in plasma samples from 40 patients with DLBCL during diagnosis and of 38 normal controls were determined with quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) for the multi-locus L1PA2 gene.

Results

Statistically significant elevation in plasma cfDNA concentrations was observed in patients with DLBCL as compared to that in normal controls (P<0.05). A cutoff point of 2.071 ng/mL provided 82.5% sensitivity and 62.8% specificity and allowed successful discrimination of patients with DLBCL from normal controls (area under the curve=0.777; P=0.00003). Furthermore, patients with DLBCL showing higher concentrations of cfDNA had shorter overall survival (median, 9 mo; P=0.022) than those with lower cfDNA levels. In addition, elevated cfDNA concentration was significantly associated with age, B-symptoms, International Prognostic Index (IPI) score, and different stages of disease (all P<0.05).

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most frequent type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and accounts for approximately 40% of NHL cases [1]. DLBCL, a varied disease with heterogeneous clinical features, is currently treated with an immunochemotherapeutic regimen. According to the gene expression study, this single diagnostic group may be divided into distinct phenotypic subgroups that differ in molecular and clinical courses to reveal the sources of specific stages of B cell follicles of secondary lymphoid organs during the germinal center reaction [23]. Over the past decade, several recurrent genetic aberrations correlating with DLBCL have been recognized.

The presence of circulating DNA in the human plasma has been known and analyzed since the late 1940s [1]. Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) mainly originates directly from the apoptotic cells of different tissues that are released into body fluids and represents a window into the health and status of numerous solid tissues [4].

cfDNA or short cell-free DNA fragment observed in human body fluids was first defined in 1948; however, the origin of cfDNA tumor cells (ctDNA) was not fully recognized until the late 1980s [5]. ctDNA source has been incompletely characterized, but it is believed to arise from apoptotic cells. The existence of ctDNA has been associated with disease activities and progression [67]. Ras and p53 mutations and tumor suppressor hypermethylation have been identified and assayed in numerous different tumors, including colon, small cell lung cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, and melanoma [89].

Quantitation of cfDNA has been suggested as a diagnostic tool for the early identification of malignant epithelial tumors, but its clinical significance in this disorder is controversial [101112]. Some recent studies have focused on the quantification of cfDNA and have performed genetic identification, subtyping, and disease monitoring after chemotherapy. For instance, cfDNA has been used to track the tumor clonotypic immunoglobulin gene rearrangement for minimal residual disease assessment [131415]. In addition, Rossi et al. [16] demonstrated that cfDNA genotyping of DLBCL is a noninvasive method to monitor the emergence of treatment-resistant clones that showed acceptable accuracy for genotyping and somatic mutation detection.

There exist some quantitative data suggestive of the prognostic role of cfDNA in hematologic malignancies, including DLBCL [131718]. cfDNA has been identified with semiquantitative techniques, and the recent introduction of quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) for some genes such as b-globin and b-actin has significantly enhanced the efficiency of detection procedures [1319].

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the plasma cfDNA levels of multi-locus L1PA2 consensus sequence as DLBCL prognostic and diagnostic tool. We hypothesize that the direct qPCR analysis [20] specific for multi-locus L1PA2 consensus sequence, which is well interspersed throughout the human genome as opposed to the single copy b-globin and b-actin measurements, leads to increased sensitivity and specificity. We used a sensitive quantitative and repeatable qPCR strategy for the multi-locus L1PA2 consensus sequence gene to determine cfDNA levels at the time of diagnosis in 40 patients with DLBCL and evaluated its association with clinical features and prognosis.

We designed a new qPCR quantification method to amplify an 86-base pair fragment of the multi-copy L1PA2 that is well scattered throughout the genome. According to the UCSC genome browser search of the human chromosome database, the assay amplifies numerous copies with a 100% match. The primer sets were designed to amplify an 86-bp fragment of multi-copy L1PA2 consensus sequence.

We evaluated the plasma specimens collected at diagnosis from 40 patients with DLBCL and healthy controls. Patient features are detailed in Table 1. Standard therapy for DLBCL is an immunochemotherapeutic regimen comprising cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) plus rituximab (R-CHOP) [21]. To establish a normal reference range for cfDNA concentration in the plasma sample, a control group comprising 38 healthy volunteers (18 yr and above without cancer history) was included. According to institutional recommendations, informed consent was obtained from all participants, and blood specimen collection was approved by our institutional ethical committee.

Peripheral blood collection from every healthy individual and patient before treatment was performed as previously described [22]. Briefly, blood specimen were obtained in 4 mL tubes containing K3-EDTA and centrifuged within 1 h. Fresh blood specimens were centrifuged at 1,000 ×g for 10 min at 4℃. The supernatants (plasma) were carefully transferred to a 0.5 mL Eppendorf tube and centrifuged for 10 min for the complete removal of any remaining cell debris. Supernatants (plasma) were aliquoted and stored at −80℃. DNA was extracted from a 0.5 mL plasma aliquot with QIAamp DNA Blood Midi Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's guidelines and stored at −20℃.

cfDNA measurement was performed with qPCR using human multi-copy L1PA2 as a reference gene. The primer sequences were as follows: Forward, 5-CGTGTGCATGTG TCTTTATAGC-3 and reverse 5-GAAATACCATTTGACCC AGCC-3 for an 86-bp fragment. The calibration curve for cfDNA concentration was obtained with a serial 10-fold dilution of genomic DNA of 10 healthy controls. As previously described, the genomic DNA concentration was determined with ultraviolet absorption measurement (UV-1800, SHIMADZU, Tokyo, Japan). The dynamic linear range of the standard curve was set at 0.01–100 ng DNA [18]. Amplification was performed on StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (applied Biosystems) and comprised a 10-min initial activation step at 95℃, followed by 40 cycles at 95℃ for 15 s and 60℃ for 1 min. After each PCR run, a melting curve study was performed to determine the specificity of the amplified product [23].

All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 20.0 software package (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Pearson's χ2 analysis or Fisher's exact test was employed to compare differences in categorical variables. Mann-Whitney U-test and Kruskal-Wallis test were used to compare differences in continuous variables. The overall survival (OS) was measured from the date of first diagnosis to the date of death from any cause. Survival curves for OS were estimated using Kaplan–Meier analysis and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated with the log-rank method. For all analyses, two-tailed P-values of 0.05 or less were determined statistically significant. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to determine an optimal cutoff value for cfDNA concentration (2−ΔCt) to divide the patients into high/low level groups according to the median value (high- and low-level, 21 and 19 cases, respectively).

The median cfDNA concentration was 1.81 ng/mL (mean, 2.4 ng/mL; range, 1.2–4.3 ng/mL) in 38 healthy individuals. The expression level of cfDNA was compared between the plasma samples from patients with DLBCL (N=40) and healthy controls (N=40). We observed higher cfDNA concentrations in DLBCL samples (N=40, median 4.6 ng/mL; mean, 5.2 ng/mL; range, 2.75–8.62; P <0.05) than in control samples (Fig. 1).

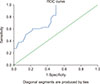

We used the ROC curve analysis to evaluate the diagnostic performance of qPCR and to discriminate between normal individuals and patients. The area under the ROC curve was 0.777 (95% CI, 0.674–0.880) for patients with DLBCL, demonstrating a moderate discriminatory power. At a cutoff value of 2.071 ng/mL, the sensitivity and specificity were 82.5% and 62.8%, respectively, for DLBCL (P=0.00003) (Fig. 2).

The relationship between cfDNA level and various clinical characteristics of DLBCL was analyzed and is summarized in Table 1. cfDNA level showed an association with some clinical features. Age >60 years, B-symptoms, International Prognostic Index (IPI) score, and different disease staging correlated with elevated levels of cfDNA (P<0.05, Table 1). However, sex and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level above the normal range showed no association with elevated cfDNA concentrations. As a consequence, DLBCL patients with a poor prognostic score had significantly elevated concentrations of cfDNA (age-adjusted IPI >2, P=0.006).

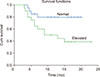

The potential role of plasma cfDNA concentrations at the time of diagnosis of DLBCL was investigated as a prognostic factor for the two main diagnostic entities included in this study. cfDNA levels were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was carried out using OS time of DLBCL cases for which the follow-up details were available (N=40) as a function of cfDNA level using the median value as a high/low cutoff. OS was calculated from the time of diagnosis to the date of death or last contact. The elevated concentrations of plasma cfDNA in patients with DLBCL correlated with OS (P=0.022). Cases with high and low cfDNA concentrations had a median OS time of 9 months (P=0.022) (Fig. 3). Moreover, the result of univariate analysis revealed that the level of cfDNA was a statistically significant predictor for OS (hazard ratio, 3.402; 95% CI, 1.097–10.552; P=0.034).

The plasma cfDNA level in patients with DLBCL has not been widely evaluated in recent years [1724]. Recent data propose a relationship between cfDNA concentration and DLBCL. Therefore, we suggest that both cfDNA level and its clinical features may be used for diagnostic applications. A few studies have demonstrated the higher concentrations of cfDNA in the blood of patients with Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma than in the blood of normal individuals, although the concentrations reported were different possibly owing to the use of different methodologies [2526].

To ensure accurate cfDNA measurement, we used qPCR that provides proper precision, reproducibility, and consistency similar to other techniques for total and amplifiable cfDNA measurement [27]. Furthermore, we used the plasma instead of serum specimens for cfDNA measurement, as the plasma isolated from EDTA-treated blood is shown to be appropriate for this analysis [282930].

We evaluated the level of cfDNA concentration and assessed the potential clinical value of cfDNA as a DLBCL diagnostic tool. The concentration of cfDNA was measured in DLBCL groups (all stages) and compared with that of normal individuals.

The ROC analysis showed that a cfDNA level with 82.5% sensitivity may serve as a useful biomarker for DLBCL prognosis. However, previous studies have shown that the maximum sensitivity and specificity of the single-copy sequence did not exceed 70% and 71%, respectively. Thus, whether this strategy is a satisfactory test for the screening of DLBCL is questionable [13]. We developed a qPCR assay that allows for the accurate and precise measurement of cfDNA levels using multi-copy sequence L1PA2 on the genome.

In our study, the patients with DLBCL had significantly elevated plasma cfDNA levels as compared with normal controls (mean, 2.4 ng/mL; range, 1.2–4.3 ng/mL; P<0.05). These findings are consistent with the previous studies, indicating that the level of cfDNA increases in DLBCL cells and may be used as a prognostic indicator of the survival of patients with DLBCL [13].

Our data demonstrate that the patients with DLBCL mostly exhibit higher levels of cfDNA at the time of diagnosis that may be correctly measured with qPCR and correlates with clinical features and prognosis. Previous studies have suggested quantification of cfDNA as a cancer screening strategy [10].

We observed a correlation between cfDNA levels and some clinical features, such as old age, different stages, and presence of B-symptoms, displaying poorer prognosis and suggesting that cfDNA may indicate an actively progressive disease. This result is in line with the findings reported by Hohaus et al. [13].

In the present study, cfDNA extraction was performed using the QIAamp DNA Blood Midi Kit, while Hohaus et al. [13] and Li et al. [24] performed cfDNA extraction using QIAamp UltraSens Virus Kit and MagMAX Cell-Free DNA Isolation Kit, respectively. QIAamp DNA Blood Midi Kit had lower DNA extraction efficiency than QIAamp UltraSens Virus Kit and MagMAX Cell-Free DNA Isolation Kit.

In line with the findings of Li et al. [24], the present study results indicate that the high cfDNA level associate with OS. Patients with DLBCL showing higher cfDNA concentration had shorter OS than that of normal controls. To our knowledge, there are no previous studies on the association between OS and cfDNA level in patients with DLBCL. Some studies have suggested an association between plasma DNA levels and freedom from treatment failure (FFTF) and progression free survival (PFS) [1324] in patients with DLBCL. Although we had a small cohort and our results should be interpreted with a caution, the association between higher cfDNA levels and shorter OS seems promising as compared to that reported previously. However, further studies are warranted.

In summary, we found that cfDNA concentration may serve as a robust prognostic predictor. Although our results need to be validated in a larger and independent cohort, the quantitation of cfDNA with qPCR may become a suitable prognostic strategy for DLBCL diagnosis.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Comparison between patients with DLBCL and normal subjects. Elevated level of cfDNA in patients with DLBCL. qPCR analysis of cfDNA level in the plasma of patients with DLBCL (N=40) and normal controls (N=38) (P<0.05).

Fig. 2

ROC curve of cfDNA concentration values. cfDNA cutoff value of 2.071 ng/mL (sensitivity 82.5%; specificity 62.8%; 95% CI, 0.674–0.880; AUC=0.777; P<0.00003). An AUC value between 0.7 and 0.8 is considered acceptable.

References

1. Campo E, Swerdlow SH, Harris NL, Pileri S, Stein H, Jaffe ES. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms and beyond: evolving concepts and practical applications. Blood. 2011; 117:5019–5032.

2. Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Davis RE, et al. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature. 2000; 403:503–511.

3. Schneider C, Pasqualucci L, Dalla-Favera R. Molecular pathogenesis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2011; 28:167–177.

4. Koh W, Pan W, Gawad C, et al. Noninvasive in vivo monitoring of tissue-specific global gene expression in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014; 111:7361–7366.

5. Stroun M, Anker P, Lyautey J, Lederrey C, Maurice PA. Isolation and characterization of DNA from the plasma of cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1987; 23:707–712.

6. Anker P, Mulcahy H, Chen XQ, Stroun M. Detection of circulating tumour DNA in the blood (plasma/serum) of cancer patients. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1999; 18:65–73.

7. Stroun M, Anker P. Circulating DNA in higher organisms cancer detection brings back to life an ignored phenomenon. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2005; 51:767–774.

8. Bettegowda C, Sausen M, Leary RJ, et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med. 2014; 6:224ra24.

9. Rapisuwon S, Vietsch EE, Wellstein A. Circulating biomarkers to monitor cancer progression and treatment. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2016; 14:211–222.

10. Sozzi G, Conte D, Leon M, et al. Quantification of free circulating DNA as a diagnostic marker in lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003; 21:3902–3908.

11. Sozzi G, Conte D, Mariani L, et al. Analysis of circulating tumor DNA in plasma at diagnosis and during follow-up of lung cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2001; 61:4675–4678.

12. Lecomte T, Berger A, Zinzindohoué F, et al. Detection of free-circulating tumor-associated DNA in plasma of colorectal cancer patients and its association with prognosis. Int J Cancer. 2002; 100:542–548.

13. Hohaus S, Giachelia M, Massini G, et al. Cell-free circulating DNA in Hodgkin's and non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Ann Oncol. 2009; 20:1408–1413.

14. Armand P, Oki Y, Neuberg DS, et al. Detection of circulating tumour DNA in patients with aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2013; 163:123–126.

15. Kurtz DM, Green MR, Bratman SV, et al. Noninvasive monitoring of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunoglobulin high-throughput sequencing. Blood. 2015; 125:3679–3687.

16. Rossi D, Diop F, Spaccarotella E, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma genotyping on the liquid biopsy. Blood. 2017; 129:1947–1957.

17. Bohers E, Viailly PJ, Becker S, et al. Non-invasive monitoring of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by cell-free DNA high-throughput targeted sequencing: analysis of a prospective cohort. Blood Cancer J. 2018; 8:74.

18. Roschewski M, Dunleavy K, Pittaluga S, et al. Circulating tumour DNA and CT monitoring in patients with untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a correlative biomarker study. Lancet Oncol. 2015; 16:541–549.

19. Lo YM, Tein MS, Lau TK, et al. Quantitative analysis of fetal DNA in maternal plasma and serum: implications for noninvasive prenatal diagnosis. Am J Hum Genet. 1998; 62:768–775.

20. Breitbach S, Tug S, Helmig S, et al. Direct quantification of cell-free, circulating DNA from unpurified plasma. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e87838.

21. Pfreundschuh M, Schubert J, Ziepert M, et al. Six versus eight cycles of bi-weekly CHOP-14 with or without rituximab in elderly patients with aggressive CD20+ B-cell lymphomas: a randomised controlled trial (RICOVER-60). Lancet Oncol. 2008; 9:105–116.

22. Ahmadvand M, Eskandari M, Pashaiefar H, et al. Over expression of circulating miR-155 predicts prognosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Res. 2018; 70:45–48.

23. Pashaiefar H, Izadifard M, Yaghmaie M, et al. Low expression of long noncoding RNA IRAIN is associated with poor prognosis in non-M3 acute myeloid leukemia patients. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2018; 22:288–294.

24. Li M, Jia Y, Xu J, Cheng X, Xu C. Assessment of the circulating cell-free DNA marker association with diagnosis and prognostic prediction in patients with lymphoma: a single-center experience. Ann Hematol. 2017; 96:1343–1351.

25. Chorostowska-Wynimko J, Szpechcinski A. The impact of genetic markers on the diagnosis of lung cancer: a current perspective. J Thorac Oncol. 2007; 2:1044–1051.

26. Ulivi P, Silvestrini R. Role of quantitative and qualitative characteristics of free circulating DNA in the management of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 2013; 36:439–448.

27. Szpechcinski A, Struniawska R, Zaleska J, et al. Evaluation of fluorescence-based methods for total vs. amplifiable DNA quantification in plasma of lung cancer patients. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008; 59:675–681.

28. Jung M, Klotzek S, Lewandowski M, Fleischhacker M, Jung K. Changes in concentration of DNA in serum and plasma during storage of blood samples. Clin Chem. 2003; 49:1028–1029.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download