Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic dermatological condition with increasing prevalence, which is becoming a major social issue.

1 Since the disease poses great economic burden and has a negative impact on the patient's daily life,

2 long-term national treatment plans should be considered.

3

A deluge of scientifically unconfirmed information from the media and alternative medicine can cause patient to misunderstand AD.

45 Moreover, fear of medical therapy may also lead to inappropriate treatment.

6 Therefore, providing proper education to patients and their caregivers is important in improving the patient's attitude toward the disease, which may ensure better treatment compliance, and eventually the overall treatment response.

78910

Although previous studies in Korea have demonstrated the need for education on AD,

11 no study has assessed how the educational programs are provided. In this study, we administered a questionnaire to clinicians who currently treat patients with AD in Korea. Through this study, we aimed to assess the education status on AD and utilize the results as a foundation for the future development of a standardized educational program in Korea.

A survey was conducted between June and September 2017 via email to all clinicians registered with the Korean Dermatological Association (KDA); Korean Academy of Pediatric Allergy and Respiratory Disease (KAPARD); and Korean Academy of Asthma, Allergy, and Clinical Immunology (KAAACI), employed at various centers. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Severance Hospital (IRB no. 4-2018-1018).

The questionnaire comprised of 22 questions, largely categorized under the following topics: 1) workplace; 2) presence of an educational program; 3) methodology used for the programs; and 4) necessary conditions for the implementation of programs.

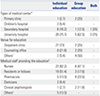

The survey was sent via e-mail to 3420 clinicians, and 153 of them (44 dermatologists and 109 pediatric allergists or allergists) responded (

Table 1). The average clinical experience duration was 17.88 years. Forty-eight participants (31.4%) were from primary private clinics, 22 (14.4%) were from secondary medical centers, and 82 (53.6%) were from tertiary centers (university hospitals). Clinicians reported the following consultation times: 14 participants (9.2%), ≤5 min; 56 participants (36.6%), 6–10 min; 55 participants (35.9%), 11–20 min; and 28 participants (18.3%), 21–30 min. No clinician spent longer than 30 min per patient. When asked about the ideal duration for education, among the 90 participants who responded, 43 participants (47.8%) indicated 15–30 min and 24 (26.7%) indicated 30–60 min to be preferable. Several responded that ≤15 min or ≥60 min would be needed [21/90 (23.3%) and 2/90 (2.2%), respectively].

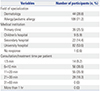

We then assessed if any additional educational programs were provided. Among the 153 participants, 41 (26.8%) said a separate program was provided. Most of these responders were from university hospitals (30 participants), followed by secondary medical centers (seven participants), private clinics (three participants), and children's hospitals (two participants). Regarding the program, 33 of 41 participating clinicians (80.5%) provided an individual-level educational program, and four (9.7%) provided a group-level program. The remaining participants (9.7%) provided both individual- and group-level programs (

Table 2).

We asked a different set of questions to the 37 clinicians who provided individual-level educational programs. Education was most often provided at the outpatient clinic (73%), whereas in some cases, a separate consultation room was used (27.6%). In very few cases, either a treatment room or a special information center was used. Group-level programs were offered at various venues, including an outpatient clinic, consultation room, hospital auditorium, and patient ward (

Table 2). Among the workforce involved in individual-level programs (multiple answers allowed), nurses were found to be most frequently involved (23 participants), followed by residents or fellows (19), dieticians (five), pharmacists (two), and clinical psychologists (one). Similar results were found for group-level programs.

We then assessed the frequency of education (

Fig. 1). For the centers that provided an individual-level program, 23 of 37 centers (62.2%) provided the program only at the time of initial diagnosis, and nine centers (24.3%) provided the program during every consultation. While some (13.5%) provided education one to three times annually, no center provided education more than four times a year. Regarding group-level education, among the eight centers, five (62.5%) provided education ≤six times per year; two centers, more than seven times per year; and one center provided education as needed. Individual- and group-level educational programs were provided for both the patients and their caregivers in 97.3% and 100% of the centers, respectively. In most cases (97.6%), no extra costs were charged for additional education.

The survey also inquired about the topics covered. Details are shown in

Fig. 2. Regarding the natural course of the disease, all centers addressed its chronicity. Among the 41 responders, 38 (92.7%) reported that the education included disease characteristics of each age group, and 36 (87.8%) reported that the associations with other allergic diseases were also included. For daily skin care, more than 92.7% of the responders said they covered topics such as lukewarm baths, moisturizer use, and coping with the urge to scratch.

Regarding the use of medications, 31 of 41 (75.6%) responders stated that proper application of topical ointments was shown through demonstration. Similarly, 24 responders (58.5%) stated that education covered wet-wrap therapy, in which 41.7% were pediatricians/allergists and 58.3% were dermatologists. Of the 41 participants, 36 (87.8%) responded that they covered proper ointment use upon symptomatic exacerbations. These indicate a relatively lower rate of detailed instructions on medication use. For the management of environmental and aggravating factors, 39 (95.1%) responders stated that the programs covered temperature and humidity management, 34 (83%) reported the benefits of wearing cotton-based clothing, and 35 (85.4%) reported the control of exposure to common allergens.

Regarding diet, only 20 responders (48.8%) said they had surveyed patients' diets. Thirty-seven (90.2%) indicated that they advised elimination of food that exacerbate symptoms, and 29 (70.7%) said the programs included education on alternative foods. Most responders (92.7%) advised against unwarranted dietary restrictions. In terms of nutritional counseling, in contrast to 27.3% of dermatologists, 73.3% of allergists said they understood the patients' nutritional status. Meanwhile, only nine (22%) provided psychologic counseling.

We also assessed the sources of data used for the programs, and multiple answers were allowed. Thirty-three (80.5%) responders stated that they developed their own educational materials. Eighteen participants utilized materials from academic societies or associations. Oral presentation was the main delivery method (35 participants), followed by handouts (32 participants) and video-based information (11 participants). Four participants used other methods, including information panels, tools, and presentation slides. Objective indices, such as Eczema Area Severity Index (EASI) and SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD), were used by 41.5% of the responders.

For 109 participants who did not provide the educational program, 58 out of 90 participants (64.4%) preferred individual-level education, whereas only 10 participants (11.1%) preferred group-level education. The remaining 24.4% of the participants indicated that both educational programs were required.

Overall, 96.7% of the participants said an additional charge was needed for education on AD. Furthermore, they mentioned that additional assistance from an academic society or association, in the form of medical staff, organized data, and advertisement, was required to provide a well-structured educational program. Eighty-seven out of 90 participants (96.7%) were willing to provide education for patients with AD if an appropriate consultation fee was provided. Therefore, with an additional budget for education on AD, more patients will surely benefit.

According to the results, only 26.8% of the centers scheduled additional time aside from the clinics to provide an appropriate education. Most of them were university hospitals, likely due to the smaller number of clinicians from private clinics in this study and greater academic interest in patient education in university hospitals. Most participants provided individual-level education, held mostly at an outpatient clinic. There was only one case where a dedicated venue for patient education was available, reflecting the scarcity of appropriate venues. Nurses primarily comprised most of the workforce involved in the programs.

Even if a separate education was provided, it was usually performed only at the initial visit. Similarly, for group-level education, most centers provided only six sessions or less per year. The appropriate management of chronic conditions requires continuous and repetitive patient education.

1213 However, education was not up to these standards in real clinical settings. Furthermore, more than one-third of the respondents reported that the average consultation time for each patient was 5–10 min, and no one spent longer than 30 min per patient. Meanwhile, the majority indicated that education should last for longer than 15 min, some even suggesting that education should be 30 min or longer. Therefore, although clinicians realize the need for additional time for education, it may be difficult to achieve under the current circumstances.

Regarding the education method, oral communication and handouts were most commonly utilized. Indeed, audio-visual materials can significantly improve patient understanding,

1415 but most centers used self-developed handouts. Therefore, a unified and reliable educational material must be developed.

The educational programs sought to thoroughly explain various aspects of the disease and its management. However, not many programs included information on the application of ointment, diet, or psychological aspects. Daily skin care is important, and direct or video demonstration would be more effective in providing adequate education for bathing and skin care.

16 It is well-known that topical therapy is fundamental; however, it should be adjusted according to the patient's conditions. Furthermore, due to the lack of understanding among caregivers, most of them seek dietary therapy to cope with AD. A survey-based study

17 showed that about 43% of the responders indicated dietary management to be most important, and more than half of the patients previously had tried dietary restriction. Dietary restrictions must be made only with confirmed food allergy,

18 and when needed, education on alternative nutrition is important to prevent malnutrition. Therefore, dieticians must also be involved in the education.

19

The deleterious effect of psychological stress in AD has been well-recognized. AD results in social intimidation and reduced quality of life.

2021 Furthermore, psychological comorbidities, including anxiety and depression, are more prevalent in patients with AD.

22 Stress then worsens the condition, leading to a vicious cycle. Also, psychological intervention and behavioral therapy against itch and scratching have been reported to improve the condition.

2324 In summary, treatment of AD needs to be supported by an educational program consisting of a team of different professionals, including dermatologists, pediatric allergists, nurses, psychological clinicians, and dieticians, and should endeavor towards a multidisciplinary approach.

25

Most of the clinicians who participated in this study asserted a need for an additional consultation fee for the education of AD, as a more proper type of education can be provided after the arrangement. Several issues, including limited time and inadequate medical staff, reportedly prevented clinicians from actively providing appropriate education in Korea. Through recognition of such needs, an appropriate consultation fee has already been adjusted for several chronic diseases, including diabetes, asthma, and cardiovascular disease, in Korea. Since AD is also a chronic disease with high prevalence, patients with AD would surely benefit from the education.

26

In Korea, five different municipal governments have established educational and informational centers for AD and asthma. However, additional manpower and time are needed to properly carry out the programs, and a more tailored protocol according to the patient's age or severity is required.

272829 As the importance of education in AD is emphasized, structured educational programs are being provided globally, especially in Europe and the United States, which are supported and funded by various organizations.

3031 Likewise, the arrangement of education fees will lead to the establishment of a structured educational program with additional medical staff in Korea.

Due to the small sample size, low response rate, and possible selection bias associated with the survey, the results do not fully represent all clinicians who manage patients with AD. Therefore, a multi-center study involving a larger number of clinicians should be performed in the future. We hope that our data will be used as baseline data for the future development of standardized education and consultation protocol for patients with AD.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download