1. Fitzpatrick TB, Goldsmith LA. Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional;2012.

2. Gisondi P, Girolomoni G. Cardiometabolic comorbidities and the approach to patients with psoriasis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009; 100(Suppl 2):14–21. PMID:

20096157.

3. Davidovici BB, Sattar N, Prinz J, Puig L, Emery P, Barker JN, et al. Psoriasis and systemic inflammatory diseases: potential mechanistic links between skin disease and co-morbid conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2010; 130:1785–1796. PMID:

20445552.

4. Ficco HM, Citera G, Cocco JA. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in psoriasis patients according to newer classification criteria. Clin Rheumatol. 2014; 33:1489–1493. PMID:

24803232.

5. Catanoso M, Pipitone N, Salvarani C. Epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis. Reumatismo. 2012; 64:66–70. PMID:

22690382.

6. Gladman DD. Psoriatic arthritis from Wright’s era until today. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2009; 83:4–8. PMID:

19661526.

7. Ritchlin CT, Colbert RA, Gladman DD. Psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376:957–970. PMID:

28273019.

8. Chin YY, Yu HS, Li WC, Ko YC, Chen GS, Wu CS, et al. Arthritis as an important determinant for psoriatic patients to develop severe vascular events in Taiwan: a nation-wide study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013; 27:1262–1268. PMID:

23004680.

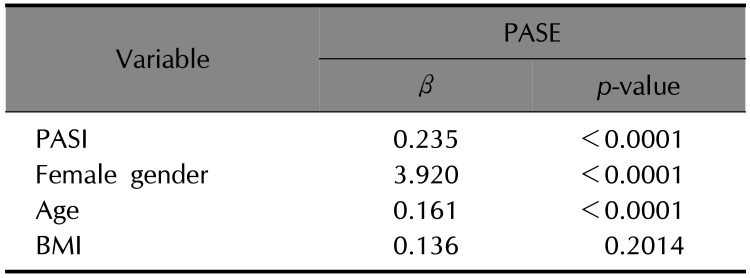

9. Husni ME, Meyer KH, Cohen DS, Mody E, Qureshi AA. The PASE questionnaire: pilot-testing a psoriatic arthritis screening and evaluation tool. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007; 57:581–587. PMID:

17610990.

10. Alenius GM, Stenberg B, Stenlund H, Lundblad M, Dahlqvist SR. Inflammatory joint manifestations are prevalent in psoriasis: prevalence study of joint and axial involvement in psoriatic patients, and evaluation of a psoriatic and arthritic questionnaire. J Rheumatol. 2002; 29:2577–2582. PMID:

12465155.

11. Ibrahim GH, Buch MH, Lawson C, Waxman R, Helliwell PS. Evaluation of an existing screening tool for psoriatic arthritis in people with psoriasis and the development of a new instrument: the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) questionnaire. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009; 27:469–474. PMID:

19604440.

12. Gladman DD, Schentag CT, Tom BD, Chandran V, Brockbank J, Rosen C, et al. Development and initial validation of a screening questionnaire for psoriatic arthritis: the Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen (ToPAS). Ann Rheum Dis. 2009; 68:497–501. PMID:

18445625.

13. Tinazzi I, Adami S, Zanolin EM, Caimmi C, Confente S, Girolomoni G, et al. The early psoriatic arthritis screening questionnaire: a simple and fast method for the identification of arthritis in patients with psoriasis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012; 51:2058–2063. PMID:

22879464.

14. Song HJ, Park CJ, Kim TY, Choe YB, Lee SJ, Kim NI, et al. The clinical profile of patients with psoriasis in Korea: a nationwide cross-sectional study (EPI-PSODE). Ann Dermatol. 2017; 29:462–470. PMID:

28761295.

15. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992; 30:473–483. PMID:

1593914.

16. Vernon MK, Revicki DA, Awad AG, Dirani R, Panish J, Canuso CM, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Medication Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ) to assess satisfaction with antipsychotic medication among schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Res. 2010; 118:271–278. PMID:

20172695.

17. You HS, Kim GW, Cho HH, Kim WJ, Mun JH, Song M, et al. Screening for psoriatic arthritis in Korean psoriasis patients using the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Evaluation questionnaire. Ann Dermatol. 2015; 27:265–268. PMID:

26082582.

18. Shin D, Kim HJ, Kim DS, Kim SM, Park JS, Park YB, et al. Clinical features of psoriatic arthritis in Korean patients with psoriasis: a cross-sectional observational study of 196 patients with psoriasis using psoriatic arthritis screening questionnaires. Rheumatol Int. 2016; 36:207–212. PMID:

26395992.

19. Dominguez PL, Husni ME, Holt EW, Tyler S, Qureshi AA. Validity, reliability, and sensitivity-to-change properties of the psoriatic arthritis screening and evaluation questionnaire. Arch Dermatol Res. 2009; 301:573–579. PMID:

19603175.

20. Baek HJ, Yoo CD, Shin KC, Lee YJ, Kang SW, Lee EB, et al. Spondylitis is the most common pattern of psoriatic arthritis in Korea. Rheumatol Int. 2000; 19:89–94. PMID:

10776686.

21. Choi HJ, Lee YJ, Park JJ, Lee JC, Lee EY, Lee EB, et al. Clinical features of Korean patients with psoriatic arthritis. Korean J Med. 2008; 74:418–425.

22. Oh EH, Ro YS, Kim JE. Epidemiology and cardiovascular comorbidities in patients with psoriasis: a Korean nationwide population-based cohort study. J Dermatol. 2017; 44:621–629. PMID:

28191654.

23. Ohara Y, Kishimoto M, Takizawa N, Yoshida K, Okada M, Eto H, et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of psoriatic arthritis in Japan. J Rheumatol. 2015; 42:1439–1442. PMID:

26077408.

24. Haroon M, Kirby B, FitzGerald O. High prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with severe psoriasis with suboptimal performance of screening questionnaires. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013; 72:736–740. PMID:

22730367.

25. Dowlatshahi EA, van der Voort EA, Arends LR, Nijsten T. Markers of systemic inflammation in psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2013; 169:266–282. PMID:

23550658.

26. Sesso HD, Buring JE, Rifai N, Blake GJ, Gaziano JM, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein and the risk of developing hypertension. JAMA. 2003; 290:2945–2951. PMID:

14665655.

27. Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ. The association between psoriasis and hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Hypertens. 2013; 31:433–442. PMID:

23249828.

28. Solak Y, Afsar B, Vaziri ND, Aslan G, Yalcin CE, Covic A, et al. Hypertension as an autoimmune and inflammatory disease. Hypertens Res. 2016; 39:567–573. PMID:

27053010.

29. Husni ME, Qureshi AA, Koenig AS, Pedersen R, Robertson D. Utility of the PASE questionnaire, psoriatic arthritis (PsA) prevalence and PsA improvement with anti-TNF therapy: results from the PRISTINE trial. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014; 25:90–95. PMID:

23688125.

30. Eder L, Haddad A, Rosen CF, Lee KA, Chandran V, Cook R, et al. The incidence and risk factors for psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016; 68:915–923. PMID:

26555117.

31. Gelfand JM, Gladman DD, Mease PJ, Smith N, Margolis DJ, Nijsten T, et al. Epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis in the population of the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005; 53:573. PMID:

16198775.

32. Langenbruch A, Radtke MA, Krensel M, Jacobi A, Reich K, Augustin M. Nail involvement as a predictor of concomitant psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2014; 171:1123–1128. PMID:

25040629.

33. Wilson FC, Icen M, Crowson CS, McEvoy MT, Gabriel SE, Kremers HM. Incidence and clinical predictors of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009; 61:233–239. PMID:

19177544.

34. Love TJ, Zhu Y, Zhang Y, Wall-Burns L, Ogdie A, Gelfand JM, et al. Obesity and the risk of psoriatic arthritis: a population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012; 71:1273–1277. PMID:

22586165.

35. Li W, Han J, Qureshi AA. Obesity and risk of incident psoriatic arthritis in US women. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012; 71:1267–1272. PMID:

22562978.

36. Thijssen E, van Caam A, van der. Obesity and osteoarthritis, more than just wear and tear: pivotal roles for inflamed adipose tissue and dyslipidaemia in obesity-induced osteoarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015; 54:588–600. PMID:

25504962.

37. Ogdie A, Gelfand JM. Clinical risk factors for the development of psoriatic arthritis among patients with psoriasis: a review of available evidence. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015; 17:64. PMID:

26290111.

38. Tey HL, Ee HL, Tan AS, Theng TS, Wong SN, Khoo SW. Risk factors associated with having psoriatic arthritis in patients with cutaneous psoriasis. J Dermatol. 2010; 37:426–430. PMID:

20536647.

39. Oyur KB, Engin B, Hatemi G, Asma A, Kutlubay Z, Bulut N, et al. Turkish PASE: Turkish version of the psoriatic arthritis screening and evaluation questionnaire. Ann Dermatol. 2014; 26:457–461. PMID:

25143673.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download