This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Dear Editor:

Traction alopecia (TA) is a type of mechanical hair loss that is provoked by constant tension on the scalp

1. Initially, scalp hair loss can be transient

2. However, as the traction force continues over a long period, scarring alopecia can occur

3. Thus, an early diagnosis and rapid intervention to stop the causative act are important

4. And TA might induce uncomfortable headache

5. Braided or pony-tailed hairstyles are common in young females due to its neatness. However, it can often result in hair loss (braids or pony tail-associated traction alopecia, BPTA) that is associated with traction force. Furthermore, this pattern of hair loss is clinically difficult to distinguish from early alopecia areata (AA).

We investigated the clinical features and dermoscopic findings of 31 cases of BPTA in 24 patients from August 2009 to August 2015. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was acquired from the IRB of the hospital (H-1701-002-051). We received the patient's consent form about publishing all photographic materials. The clinical assessment included the age; sex of patients; the location, number, and size of the hairless patches; disease duration; onset of the disease; histories of treatment on the hairless patches at the local clinic; and the clinical course of the disease. As a dermoscopic control group, 81 small round or oval hairless patches in 65 AA patients were also investigated.

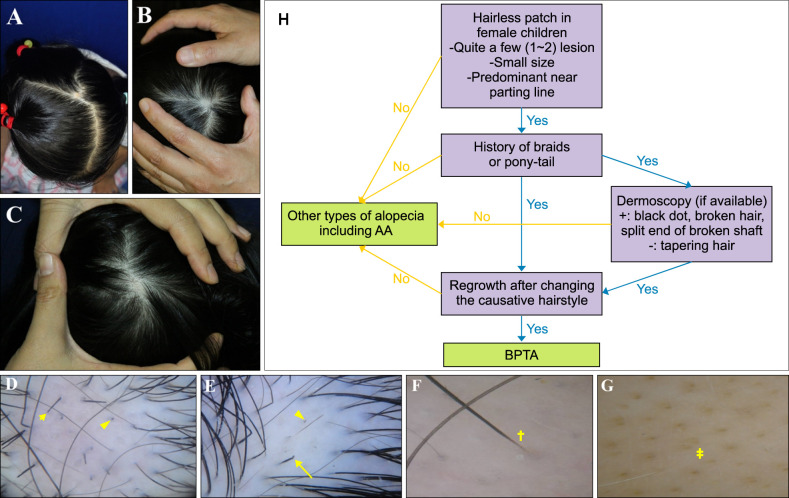

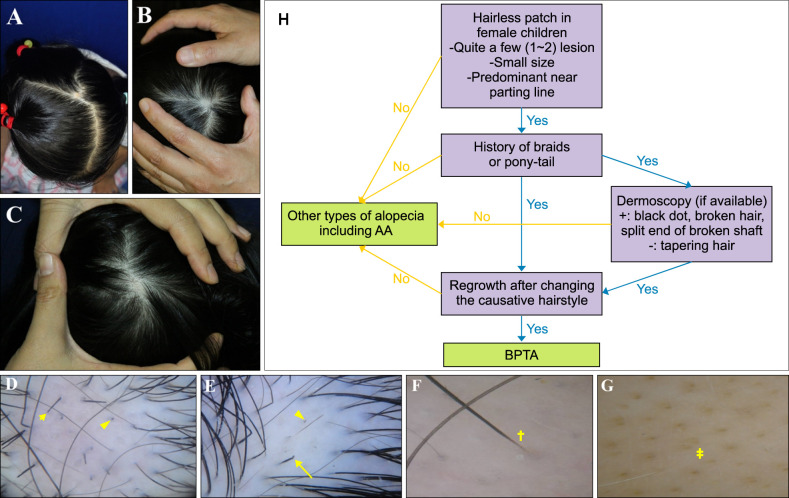

All BPTA patients were female children (mean age of 5.92 years), 19 lesions (19/31, 61.29%) were located on frontal and midscalp, seven lesions (7/31, 22.58%) on occiput and five lesions (5/31, 16.13%) on temporal area (

Fig. 1). Overall, the location of hairless patch was predominant near the parting lines of the scalp (26/31, 83.87%). The duration of the disease was short with a mean value of 1.2 months. The mean duration of the onset of the hairless patch after admission to kindergarten was 4.4 months. There were either one or two lesions per child, with the mean number of lesions being 1.48. The hairless patches were similar in size to their thumb nail plate and round to oval in shape in most patients. The clinical course showed spontaneous regrowth in all patients within 1.5 months of the mean value after changing the causative hairstyle. Moreover, 37.5% (9/24) of patients underwent treatment with triamcinolone intralesional injection or topical therapy, such as steroid and minoxidil, under misdiagnosis of AA at the local clinic.

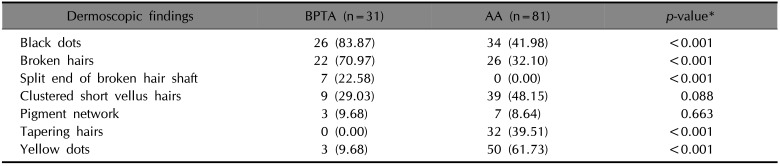

| Fig. 1Braids or ponytail-associated traction alopecia (BPTA) and alopecia areata (AA). Clinical features of BPTA in girl children: (A) 3-year-old girl, (B) 5-year-old girl, and (C) 4-year-old girl. Dermoscopic findings of BPTA and AA: (D) broken hair (short arrow) and black dot (arrow head) in a 4-year-old girl with BPTA, (E) split end of broken hair shaft (long arrow) and black dot (arrow head) in a 7-year-old girl with BPTA, (F) tapering hair (cross) in a 7-year-old girl with AA, and (G) yellow dot (double cross) in a 5-year-old girl with AA. (H) Diagnostic algorithm for braids or pony-tail associated traction alopecia.

|

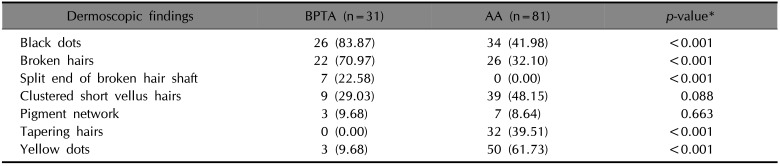

In BPTA, black dots were the most common finding and occurred in 83.87% (26/31) lesions. This was followed by broken hairs (22/31, 70.97%) and clustered short vellus hairs (9/31, 29.03%). Split ends of the broken hair shaft, pigment network and yellow dots were observed in seven (7/31, 22.58%), three (3/31, 9.68%) and three (3/31, 9.68%) patients, respectively. Nevertheless, tapering hair was not observed in all lesions. In AA, the most common finding was yellow dots (50/81, 61.73%), followed by clustered short vellus hairs (39/81, 48.15%), black dots (34/81, 41.98%), tapering hairs (32/81, 39.51%), broken hairs (26/81, 32.10%) and pigment network (7/81, 8.64%). Split ends were not found in all lesions (

Fig. 1,

Table 1).

Table 1

Comparision of dermoscopic findings between braids or pony tail-associated traction alopecia (BPTA) and alopecia areata (AA)

|

Dermoscopic findings |

BPTA (n=31) |

AA (n=81) |

p-value*

|

|

Black dots |

26 (83.87) |

34 (41.98) |

<0.001 |

|

Broken hairs |

22 (70.97) |

26 (32.10) |

<0.001 |

|

Split end of broken hair shaft |

7 (22.58) |

0 (0.00) |

<0.001 |

|

Clustered short vellus hairs |

9 (29.03) |

39 (48.15) |

0.088 |

|

Pigment network |

3 (9.68) |

7 (8.64) |

0.663 |

|

Tapering hairs |

0 (0.00) |

32 (39.51) |

<0.001 |

|

Yellow dots |

3 (9.68) |

50 (61.73) |

<0.001 |

In our study, most lesions of BPTA were located in the central part of the scalp, particularly near parting lines. We speculated that BPTA mostly occurred near parting lines because hair is parted along the midline with an exact proportion of five to five in Korean braided or pony- tail hairstyles. This is in contrast with TA caused by hairstyles among Afro-Caribbean women, where hairless patches occur most frequently in the temporal area because of an elevated level of tension on the marginal area of the scalp because of the nature of the characteristic African female hairstyle

6. The number of alopecic lesions in patients was one or two, with the mean being 1.48. The hairless patch was also found to be similar in size to the thumb nail plate of the patients. Considering these clinical characteristics, diagnosing BPTA is not difficult. However, 37.5% of patients were misdiagnosed and treated with AA at their local clinic before visiting our department.

In dermoscopic findings of BPTA, black dots, broken hairs and split ends of broken hair shafts were observed with statistical significance compared with AA. Tapering hairs and yellow dots were dermoscopic features of AA in our study, which is similar to previous reports

7. The present dermoscopic findings of BPTA are considered to be partially consistent with those of a previous study of TA

8. In particular, black dots upon dermoscopic investigation are regarded as a sign of broken hairs

9. Growing hair shafts (i.e., during the anagen phase) that is broken by traction force manifests itself as broken hairs

8. Characteristically, split ends of broken hair shafts, which are reported in the dermoscopic findings of trichotillomania, were observed in this study in patients with BPTA. But, BPTA could be differentiated from trichotillomania clinically in the aspect of round to oval in shape, central part of the scalp in lesion location and the absence of concurrent manifestation other than alopecia such as onychophagia. Split ends of broken hair shafts upon dermoscopic investigation generally intimates irregular and repetitive pulling of hair, thereby resulting in cumulative damage to the shaft

10. Repetitive and persistent tension on the cuticle that is induced by braids or the ponytail hairstyle may have contributed to the genesis of the split ends of broken hair observed in the present study.

When encountering focal hairless patches in female children, it is important to discern the history of use of braids or the pony-tail hair style if there are lesions on the parting lines of the scalp that are one to two lesions that are small in size and that persist for a relatively short duration. This will allow for the identification of BPTA. In ambiguous cases, dermoscopy might help in differentiating BPTA from other types of alopecia, particularly early AA. If black dots, broken hairs and split ends of broken shafts are found upon dermoscopy, the diagnostic possibility of BPTA increases. If the patient's clinical and dermoscopic findings correspond to BPTA, physicians can observe spontaneous regrowth after changing the causative hair style in approximately 2~3 months to confirm the diagnosis of BPTA (

Fig. 1).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download