Abstract

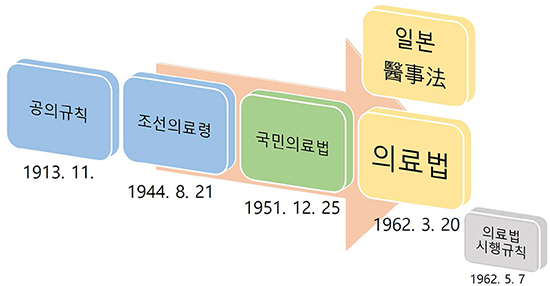

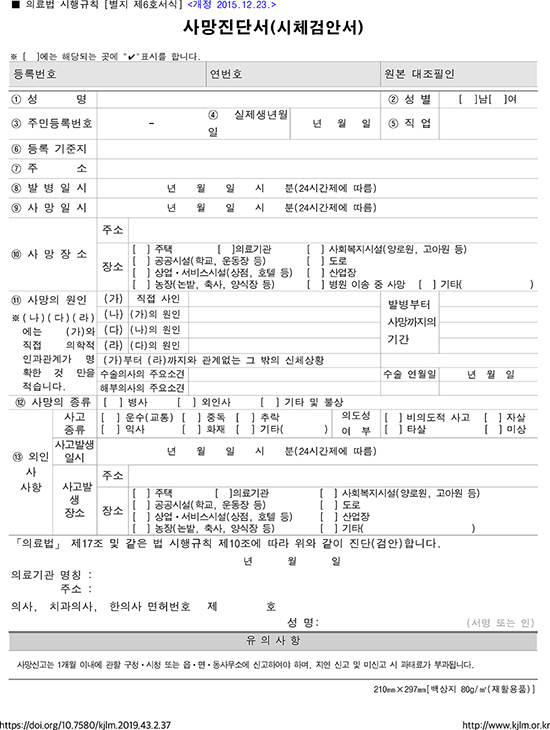

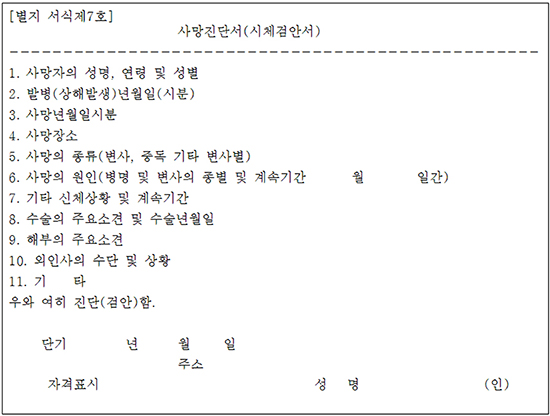

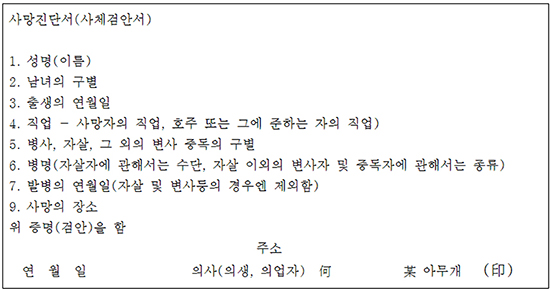

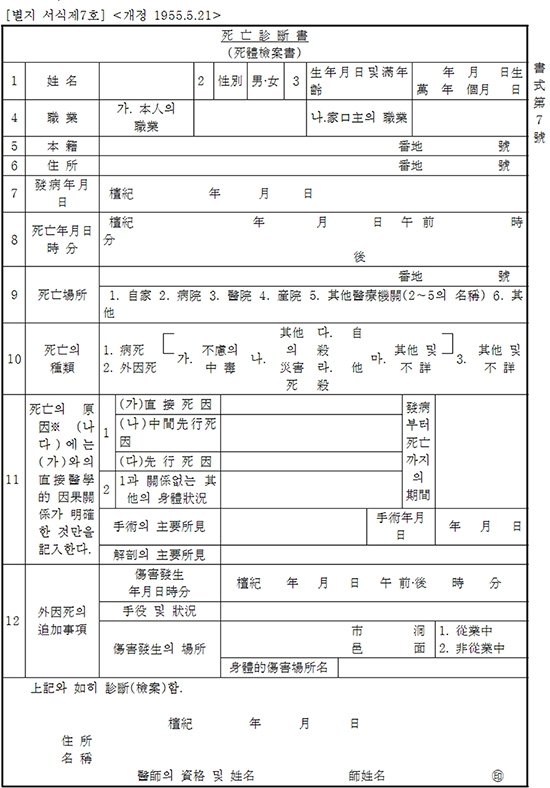

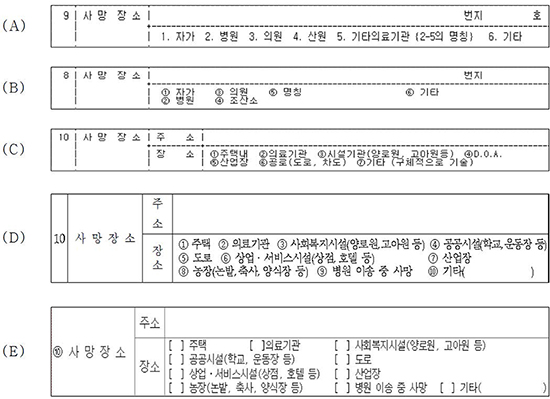

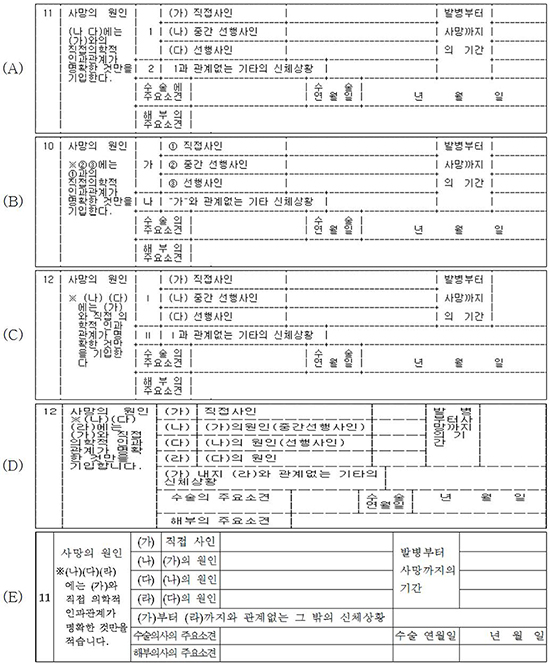

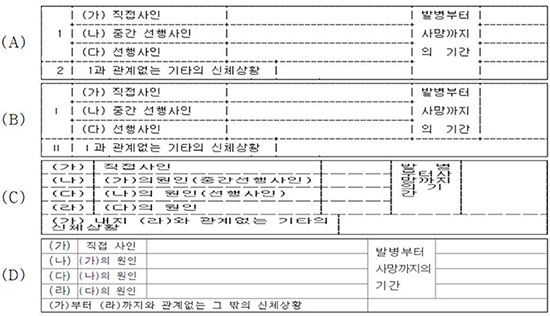

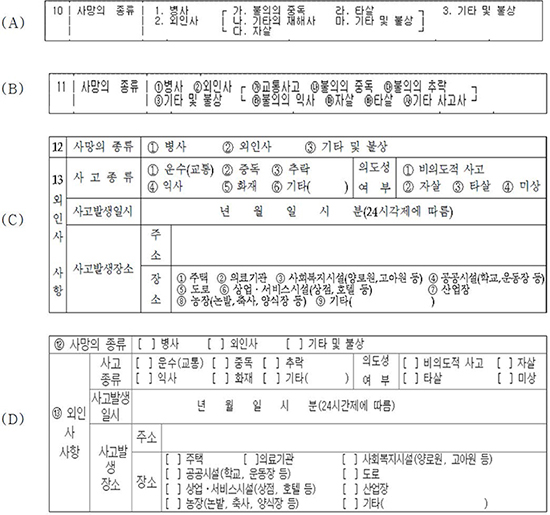

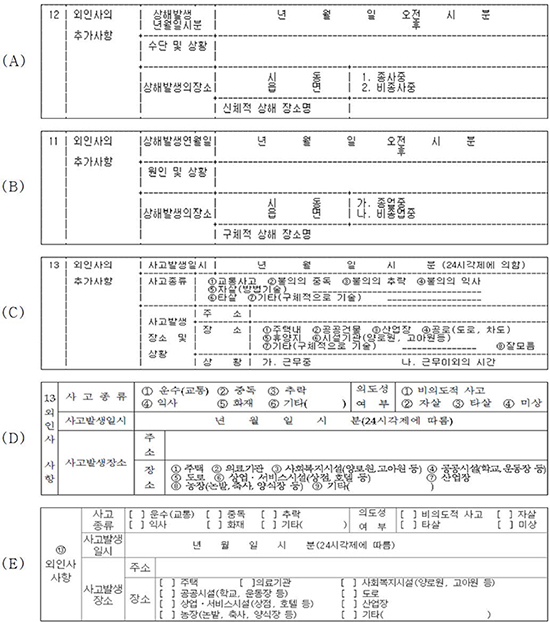

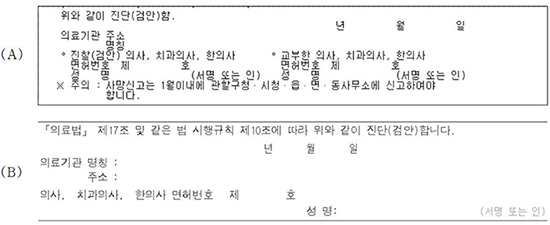

The death certificate is a medical document that proves the death of a person and forms the basis of an administrative death report. It is a source of statistics on the cause of a person's death and the basic tool used in national health policy and health promotion activities. This study reviews the major categories of historical changes made to the Korean death certificate form over the years. During the Japanese colonial period, the death certificate form was first introduced under the Koii (public doctor) system. However, the first structurally organized form of the death certificate was based on the “National Medical Service Act” (June 26, 1955.); it was structurally very similar to the current form. Since the enactment of the “Enforcement Decree of the Medical Service Act”, the death certificate form has undergone structural changes 13 times. The changes made to the contents or format of the death certificate during its 98 revisions can be classified into eight categories: death certificate title, form language, personal information, place of death, cause of death, manner of death, information on unnatural death, and other changes (chart number, serial number, confirmation seal, etc.). The authors hope that future revisions to the Korean death certificate would make it easier to write.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Death certificate form was first introduced in the official gazette (No. 601: 1914.8.3.) by Chosun Governor General in Japanese colonial period. |

| Fig. 2International standard form of medical certificate of “cause of death.” Reproduced from World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016 [2]. |

References

1. Korean Medical Association. How to write and issue medical certificates [Internet]. Seoul: Korean Medical Association;2015. cited 2018 Feb 2. Available from: http://hospice.cancer.go.kr/hospice/front/boardView.do?keykind=&keyword=&page_now&returl=/front/boardList.do&listurl=/front/boardList.do&brd_mgrno=181&menu_no=442&brd_no=88452.

2. World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization;2016. cited 2018 Feb 2. Available from: http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en.

3. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Burden of Disease Study 2016 (GBD 2016) data resources [Internet]. Seattle: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation;2016. cited 2018 Feb 2. Available from: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2016.

4. Yoon SH, Kim R, Lee CS. Analysis of death certificate errors of a university hospital emergency room. Korean J Leg Med. 2017; 41:61–66.

5. Moon M. A comparative study on Koii (public doctor) system and its effect on public health in colonial Taiwan and Korea. Korean J Med Hist. 2014; 23:157–202.

6. Lee J. State control of medicine through legislation and revision of the medical law: licensed and unlicensed medical practices in the 1950s–60s. Korean J Med Hist. 2010; 19:385–432.

7. National Archives of Korea. The path of Korean letters: only use the Korean letters in official documents, 1958 [Internet]. Daejeon: National Archives of Korea;1958. cited 2018 Feb 2. Available from: http://theme.archives.go.kr/next/hangeulPolicy/practice.do.

8. National Archives of Korea. The path of Korean letters: mixed using era of Korean and Chinese letters in the textbook, 1963–1971 [Internet]. Daejeon: National Archives of Korea;1971. cited 2018 Feb 2. Available from: http://theme.archives.go.kr/next/hangeulPolicy/viewMain.do.

9. Yoon JW, Lee HG, Choo CM. 2015 Knowledge Sharing Program: The evolution of the resident registration system in Korea (The government publishing number 11-1051000-000675-01) [Internet]. Sejong: Ministry of Economy and Finance, KDI International Policy Graduate School;2015. cited 2018 Feb 2. Available from: https://www.kdevelopedia.org/resource/view/04201604190144217.do#.XMWRh2gzZPY.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download