Abstract

Endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) that arises from extrauterine endometriosis is a rare form of malignancy. We report the case of a 37-year-old ESS patient with extrauterine endometriosis who was treated with ifosfamide/cisplatin chemotherapy. A woman presented with epigastric pain and abdominal distension. Computed tomography imaging revealed a profuse amount of ascites, including a 12.4×12.3 cm sized posterior cul-de-sac mass composed of solid and cystic components. Cytoreductive surgery was performed to remove the mass and the histopathologic findings indicated ESS associated with extrauterine endometriosis. Six cycles of combination chemotherapy [ifosfamide (5 g/m2) with mesna (1 g/m2) and cisplatin (50 mg/m2) (IP)] were administered. After a six-month of disease-free interval, recurrent ESS developed in the pelvic cavity and in both lung fields. Megace medication decreased tumor marker CA-125 for six weeks. However, the patient expired sixteen months after the cytoreductive surgery. ESS associated with extrauterine endometriosis showed response to IP chemotherapy and megace.

Endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) that arises from extrauterine endometriotic foci is a very rare type of neoplasm. Malignant transformation of endometriosis occurs in 0.7% to 1% of cases.1 In 76% of the cases, the ovary is the primary site of malignancy, whereas extragonadal sites represent 24% of tumors.2,3 Although any histologic pattern can arise in endometriosis, ESS is an extremely rare histologic type.2 Previous study reported that sarcoma, including mixed mesodermal tumor was 11.6% of all malignant neoplasms arising in endometriosis.4

ESS shows invasion of both the myometrium and vascular spaces. ESS has traditionally been stratified on the basis of the mitotic index and divided into low-grade and high-grade tumors. However, highgrade tumors lack the typical growth pattern and vascularity observed in low-grade ESS: The high-grade ESS conducts a destructive myometrial invasion, rather than the permeate invasion of a low-grade ESS.5 Moreover, this form of the neoplasm demonstrates a marked cellular pleomorphism and brisk mitotic activity. As a result, the designation 'ESS' is now restricted to malignancies that were previously referred to as low-grade stromal sarcomas.5-7 Endometrial sarcomas without recognizable evidence of a definite endometrial stromal phenotype, designated as poorly differentiated endometrial sarcomas, are almost invariably high grade6,7 and called poorly differentiated or undifferentiated uterine sarcomas.

We present a case of ESS arising from endometriosis that was treated by six cycles of Ifosfamide and cisplatin (IP) chemotherapy.

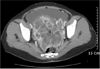

A 37-year-old, gravida 2 para 0, unmarried female presented with primary complaints of epigastric pain and a distended abdomen. She had no symptoms to suggest endometriosis except mild dysmenorrhea. However, abdomino-pelvic CT scanning showed massive ascites and a 12.4×12.3 cm sized solid mass with cystic components (Fig. 1).The tumor marker CA-125 level was 961 IU/ml (normal <35). A chest x-ray posterior-anterior view revealed pleural effusion. However, pleural tapping did not show malignant cells.

At the time of surgery, the peritoneal cul-de-sac was totally obliterated by the tumor mass and the mass had extended beyond the pelvic brim. There was a large amount of ascites (about 3 L) in the peritoneal cavity. The tumor was friable and adhered to the uterus, bilateral adnexae, rectum, sigmoid colon, small intestine and pelvic wall. However, the upper abdomen, omentum and diaphragmatic surfaces were normal in appearance. Examination of the frozen section of the mass showed malignancy but accurate cell types could not be classified. Under the impression that this was ovarian cancer, cytoreductive surgery was performed. A total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, supracolic omentectomy, tumorectomy, appendectomy, pelvic lymph node dissection and paraaortic lymph node sampling were conducted. All of the posterior cul-de-sac mass was removed. In order to control bleeding, all the tumor bases were electrocauterized with Argon beam electrocautery (Valleylab Force FX C Electrosurgical Generator).

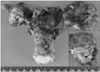

Diffuse, irregular soft tissue nodules on the external surfaces of the uterus, both ovaries and fallopian tubes were observed. No intraparenchymal lesions were present on the right ovary (Fig. 2). The ovarian surface revealed an endometriotic lesion and abundant proliferating tumor cells in continuity (Fig. 3A). The tumor from the ovarian surface was composed of high cellular nodules and revealed mitotically active small uniform cells resembling those of proliferative-phase endometrial stroma and regularly distributed small blood vessels that resemble spiral arterioles (Fig. 3B). The mesosalpinx showed the tumor mass with no intraparenchymal lesion of the salpinx. Endometriosis was found on the posterior wall of the uterus. The endometrium was in a proliferative phase and no intrauterine tumor was present. Endometriotic foci were found in close relationship with the endometrial stromal sarcoma, of which the glandular epithelium demonstrated cytokeratin by immunohistochemistry. The tumor was strongly and diffusely positive for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor (Fig. 4A and 4B), vimentin and Ki-67 (50%). However, BerEP4, CD10 (Fig. 4C), and inhibin-α were all negative.

The patient's postoperative course was uneventful, and six cycles of combination chemotherapy with ifosfamide (5 g/m2) and mesna (1 g/m2) and cisplatin (50 mg/m2) every three weeks were given. After the first cycle of chemotherapy, the tumor marker CA-125 decreased to a normal range (33.9 IU/ml), and then to 6.8 IU/ml, after the sixth cycle. Because she did not present any imaging abnormalities or symptoms, chemotherapy was terminated. She was prescribed provera (10 mg per os every day) due to complaints of facial flushing and sweating. Three months post-chemotherapy, the CA-125 marker rose to 9.11 IU/ml; by six months post-chemotherapy and ten months post-surgery, the patient's CA-125 marker rose to 146 IU/ml. PET-CT showed hypermetabolic lesions around the rectum, cul-de-sac and both lung fields. We started megace (80 mg po bid) which decreased the CA-125 marker from 146 IU/ml to 50 IU/ml. Six weeks later, the patient visited the hospital's emergency room complaining of a distended abdomen and dyspnea. A profuse amount of pleural effusion was controlled by pleural tapping and pleurodesis. Another two cycles of IP chemotherapy failed to control the disease. The patient died sixteen months after surgery (six months of progression-free survival).

Endometriosis is defined by the presence of endometrial glands and stroma in regions outside the uterine cavity and is known as one of the most common benign gynecologic condition.3 Malignant transformation of endometriosis in gonadal and extragonadal sites has been well documented despite being a rare phenomenon. A previous study reported that about 0.7-1.0% of patients with endometriosis have lesions that undergo malignant transformation, and that the most frequently involved transformation site was the ovary (76%). Of the remaining 24% of tumors, extragonadal tumors were present in the pelvis (5.4%), rectovaginal septum (4.0%), colon/rectum (5.0%) and vagina (1.8%).4 Although the exact incidence has not been clearly reported, ESS has been known to be an extremely rare neoplasm that arises from endometriosis. The criteria for diagnosis of a malignancy arising in endometriosis are 1) demonstration of a clear example of the endometriosis in proximity to the tumor, 2) no other primary site for the tumor, and 3) histologic appearance consistent with an origin from endometriosis.8 However, direct progression of ESS from endometriosis has not yet been demonstrated. Moreover, several studies reported some cases of extrauterine ESS not associated with endometriosis.9,10 Thus, the diagnostic criteria for of ESS associated with extrauterine endometriosis are thought to be insufficient.

The division of ESS into low-grade and high-grade categories has been abandoned. The designation of ESS is now considered best restricted to neoplasms that were formally referred to as 'low-grade' stromal sarcoma.11 Endometrial sarcomas without recognizable evidence of a definitive endometrial stromal phenotype, designated poorly differentiated or undifferentiated endometrial sarcomas are almost invariably high grade.7,11 Immunohistochemical study has been useful in differential diagnosis: 'Low-grade' ESS commonly expresses estrogen and/or progesterone receptors, but 'high-grade' ESS does not express these receptors.12 All of the 'low-grade' ESS show CD 10 expression by immunohistochemistry13,14 and 'high-grade' ESS in only 67% of cases.13 Although our present case does not show direct progression from endometriosis, it satisfies criteria as a malignant transformation of endometriosis and, as newly defined, can be referred to as ESS malignancy. However, our present case is negative for CD 10 in spite of strong positivity for estrogen and progesterone receptors.

We cannot explain these discrepancies between diagnosis and CD 10 expression.

The treatment recommendation for ESS is cytoreductive surgery. Adjuvant therapy, such as radiation and chemotherapy, has been tried but has not proven to be effective. For ESS, hormonal therapy is considered to be useful,15 but it has been suggested that the presence of estrogen and progesterone receptors in ESS is associated with sensitivity to progestin therapy.16 The median time between hysterectomy and relapse of ESS has been reported as 5.4 years for stage I, and 9 months for stages III-IV.17 NCCN practice guidelines in oncology (v.1.2004), recommend hormone therapy for stage III ESS, and radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy or hormone therapy for stage IV. Salvage therapy of disseminated asymptomatic recurrent ESS are recommended hormone therapy. Several reports on the use of cytotoxic agents in uterine sarcomas have been published. However, most of these studies included a heterogeneous group of uterine sarcomas, and the numbers were too small to draw conclusions from subgroups. Furthermore, in reports addressing chemosensitivity of endometrial stromal tumors, the distinction between formerly called low-grade ESS (currently called ESS) and high-grade ESS (currently called undifferentiated or poorly differentiated uterine sarcomas) was not made.5 However, previous studies suggested that a combination containing doxorubicin would be preferred in ESS.18 Ifosfamide has been reported active in the therapy of patients with chemotherapy-naіve metastatic or recurrent endometrial stromal sarcoma.19 Cisplatin-based chemotherapy has been reported active in ESS.20 We applied the NCCN guidelines to our case. Although the patient showed strong estrogen and progesterone receptors, we nevertheless used IP chemotherapy every three weeks, because the staging of this case was obscure and thought to be stage IV.

In summary, this case of ESS associated with endometriosis in the cul-de-sac responded to six cycles of IP chemotherapy after cytoreductive surgery. Six months after chemotherapy, she recurred and showed response to hormonal therapy for six weeks.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Abdomino-pelvic CT finding shows profuse amount of ascites and 12.4×12.3 cm mass composed of solid and cystic components (‡).

Fig. 2

Gross specimens shows diffuse irregular soft tissue nodules on the external surfaces of the uterus, both ovaries and fallopian tubes. No intraparenchymal lesion is present in the right ovary (inset).

Fig. 3

(A) Extrauterine (mesenteric) tumor nodules show diffuse proliferation of small cells (Original magnification, ×40). (B) High magnification of the tumor shows diffuse proliferation of tumor cells with frequent mitosis and conspicuous spiral arteriole-like vessels resembling endometrial stroma (Original magnification, ×400). (C) The tumor is present at the ovarian surface (*) and foci of endometriosis (**) are often noted in continuity with the tumor (Original magnification, ×12.5).

References

1. Lauslahti K. Malignant external endometriosis. Acta pathol Immunol Microbiol Scand [Suppl]. 1972. 223:98–102.

2. Mourra N, Tiret E, Parc Y, de Saint-Maur P, Parc R, Flejou JF. Endometrial stromal sarcoma of the rectosigmoid colon arising in extragonadal endometriosis and revealed by portal vein thrombosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001. 125:1088–1090.

3. Irvin W, Pelkey T, Rice L, Andersen W. Endometrial stromal sarcoma of the vulva arising in extraovarian endometriosis: A case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 1998. 71:313–316.

4. Heaps JM, Nieberg RK, Berek JS. Malignant neoplasms arising in endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1990. 75:1023–1028.

5. Amant F, Woesrenborghs H, Vandenbroucke V, Beteloot P, Neven P, Moperman P, et al. Transition of endometrial stromal sarcoma into high-grade sarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2006. 103:1137–1140.

6. Evans HL. Endometrial stromal sarcoma and poorly differentiated endometrial sarcoma. Cancer. 1982. 50:2170–2182.

7. Oliva E, Clement PB, Young RH. Endometrial stromal tumors: An update on a group of tumors with a protean phenotype. Adv Anat Pathol. 2000. 7:257–281.

8. Sampson J. Endometrial carcinoma of the ovary, arising in endometrial tissue in that organ. Arch Surg. 1925. 10:1–72.

9. Chang KL, Crabtree GS, Lim-Tan SK, Kempson RL, Hendrickson MR. Primary extrauterine endometrial stromal neoplasms: A clinicopathologic study of 20 cases and a review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1993. 12:282–296.

10. Fukunaga M, Ishihara A, Ushigome S. Extrauterine low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma: Report of three cases. Pathol Int. 1998. 48:297–302.

11. Amant F, Vergote I, Moerman P. The classification of a uterine sarcoma as 'high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma' should be abandoned. Gynecol Oncol. 2004. 95:412–413. author reply 13.

12. Sabini G, Chumas JC, Mann WJ. Steroid hormone receptors in endometrial stromal sarcomas: A biochemical and immunohistochemical study. Am J Clin Pathol. 1992. 97:381–386.

13. McCluggage WG, Sumathi VP, Maxwell P. CD10 is a sensitive and diagnostically useful immunohistochemical marker of normal endometrial stroma and of endometrial stromal neoplasms. Histopathology. 2001. 39:273–278.

14. Chu PG, Arber DA, Weiss LM, Chang KL. Utility of CD10 in distinguishing between endometrial stromal sarcoma and uterine smooth muscle tumors: An immunohistochemical comparison of 34 cases. Mod Pathol. 2001. 14:465–471.

15. Kusaka M, Mikuni M, Nishiya M. A case of high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma arising from endometriosis in the cul-de-sac. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006. 16:895–899.

16. Katz L, Merino MJ, Sakamoto H, Schwartz PE. Endometrial stromal sarcoma: A clinicopathologic study of 11 cases with determination of estrogen and progestin receptor levels in three tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 1987. 26:87–97.

17. Chang KL, Crabtree GS, Lim-Tan SK, Kempson RL, Hendrickson MR. Primary uterine endometrial stromal neoplasms: A clinicopathologic study of 117 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990. 14:415–438.

18. Goff BA, Rice LW, Fleischhacker D, et al. Uterine leiomyosarcoma and endometrial stromal sarcoma: Lymph node metastases and sites of recurrence. Gynecol Oncol. 1993. 50:105–109.

19. Sutton G, Blessing JA, Park R, DiSaia PJ, Rosenshein N. Ifosfamide treatment of recurrent or metastatic endometrial stromal sarcomas previously unexposed to chemotherapy: A study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Obstet Gynecol. 1996. 87:747–750.

20. Yoshino N, Iwanari O, Miyako J, Ryukou K, Date Y, Moriyama M, et al. Metastatic endometrial stromal sarcoma successfully treated by intra-arterial hypertension chemotherapy with CDDP and ADM. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1990. 17:1773–1776.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download