This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Background

To translate into Korean and culturally adapt the anterior cruciate ligament-return to sports after injury (ACL-RSI) scale assessing psychological readiness to return to sports after ACL reconstruction and to validate its psychometric properties.

Methods

The ACL-RSI scale was forward translated into Korean and back-translated into English for cultural adaptation according to the standardized guideline. For validation, the Korean version of the ACL-RSI (ACL-RSI Kr) was administered to patients who underwent ACL reconstruction. The following subjective questionnaires were also administered: International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Evaluation Form (IKDC-SKF), Lysholm scale, Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), and a Return to Sports Questionnaire. Test-retest reliability, internal consistency, content validity, construct validity, and discriminant validity of the ACL-RSI Kr were assessed.

Results

A total of 129 patients (102 men and 27 women) were included in the study. Their mean age was 28.3 years. The average follow-up duration was 13.2 months. Test-retest reliability was remarkable (intraclass correlation coefficient, 0.949), internal consistency was high (Cronbach's alpha, 0.932), and floor and ceiling effects were confirmed to be less than 10%. Construct validity assessed by correlation analysis with KOOS, IKDC-SKF, and Lysholm scale showed the correlation coefficients ranging from 0.169 to 0.679 (all p < 0.01). Compared with the Return to Sports Questionnaire, statistically significant difference was found in the ACL-RSI Kr between patients who received more than 7 points and less than 7 points (72.2 vs. 60.3, p = 0.025) for performance level scored using a 10-point Likert scale, proving its discriminative value.

Conclusions

The ACL-RSI Kr demonstrated good psychometric properties. This scale can be an excellent instrument for evaluating patient's psychological readiness to return to sports after ACL injury.

Go to :

Keywords: Anterior cruciate ligament, Patient reported outcome, Return to sports, Translation

The decision to return to sports after anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury is one of the most debatable issues recently. Among various factors related to the ability to return to sports,

1) knee range of motion, quadriceps strength, and functional test performance have been commonly used as criteria to determine when patients can return to sports.

23) However, a meta-analysis reported that only 63% of patients return to their preinjury-level sports after ACL reconstruction in spite of good-to-excellent International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Evaluation Form (IKDC-SKF) scores.

4) This serves as strong evidence that psychological factors, such as fear of pain and reinjury and lack of confidence, greatly influence return to sports.

45) A systematic review by Czuppon et al.

6) showed that some psychological factors are important for athletes to return to sports; it provided meaningful evidence on the association of psychological factors with return to sports.

The ACL-return to sports after injury (ACL-RSI) scale was developed in 2007 to assess the psychological factors influencing return to sports.

7) It was validated by standardized statistical methods and has been used as a predictor of return to sports or indicator of readiness for return to sports in patients with ACL injury.

8) The scale was originally developed in English, and it has been translated and adapted into different languages through the cross-cultural adaptation process.

3910) The primary purpose of this study was to translate the ACL-RSI in Korean to assess the patient's psychological readiness to return to sports after ACL reconstruction in Korean patients. The second purpose was to validate the Korean ACL-RSI scale.

METHODS

Translation and Cross-cultural Adaptation

Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the ACL-RSI scale were conducted in six stages based on the methods described by Guillemin.

11) Stage 1 involved forward translation from English to Korean by two uninformed translators who were native Koreans fluent in English. In stage 2, the two translated versions were combined into one version; any discrepancies were resolved under the supervision of one methodologist. In stage 3, backward translation (from Korean to English) of the combined version was performed independently by two native English speakers who were fluent in Korean. Stage 4 comprised a consensus meeting of all persons involved in the translation process to resolve any remaining problems, ambiguities, and discrepancies and to establish a pre-final Korean version. Stage 5 involved pretesting of the Korean version in 20 consecutive patients who underwent ACL reconstruction in one hospital to examine the accuracy of wording and ease of understanding of the questionnaire. Finally, in stage 6, a validation study was conducted in 129 patients from seven institutions, who underwent ACL reconstruction surgery between 6 months and 2 years before the study.

Validation

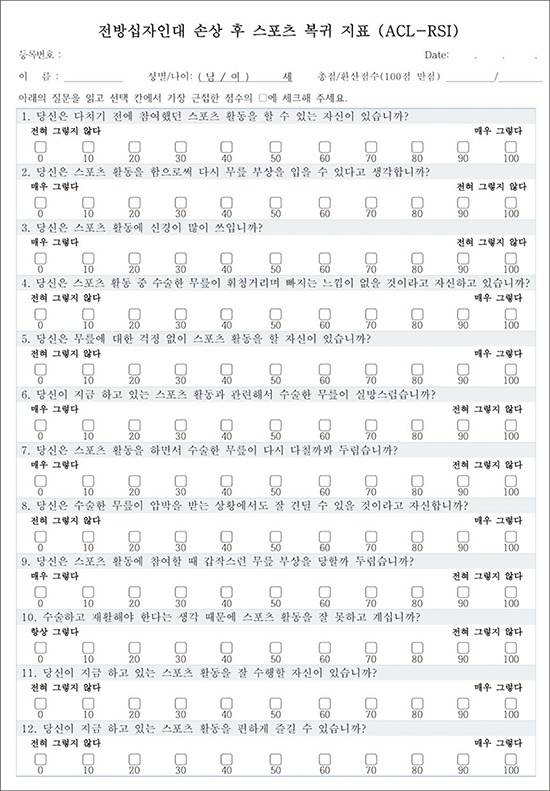

The Korean version of the ACL-RSI (ACL-RSI Kr) (

Appendix 1) was administered to the patients with other questionnaires (IKDC-SKF, Lysholm scale, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score [KOOS], and Return to Sports Questionnaire). The IKDC-SKF contains 18 items designed to assess symptoms (pain, stiffness, swelling, joint locking, and joint instability) and function to perform daily living activities and sports in patients with knee disorders including ligamentous and meniscal injuries, osteoarthritis, and patellofemoral dysfunction.

12) The Lysholm scale is an eight-item questionnaire designed to evaluate the clinical outcomes of knee ligament surgery with respect to joint stability, pain, locking, swelling, stair climbing, limping, use of a support, and squatting on a 100-point scale.

13) This scale has been used in clinical research and has good construct validity and adequate test-retest reliability. The KOOS evaluates subjective knee function and has five subdomains: symptoms, pain, function in daily life, and function during sport and recreational activity, and knee-related quality of life (QOL).

14) The score for each subdomain ranges from 0 to 100 with a score of 100 indicating good knee function. The Return to Sports Questionnaire was devised by the authors. It includes four items asking whether the patient returned to sports or not, timing of return to sports, satisfaction of functional recovery, and performance level compared with the preinjury level.

We conducted this study in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol of this study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul Paik Hospital (IRB No. 2016-07-007-001). Written informed consents were obtained.

Psychometric Properties

Several statistical concepts were used to evaluate the psychometric properties of the instrument. Internal consistency is a measure of how well the individual item in a tool “hang” together.

15) Test-retest reliability has the concept that repeated administration of a measurement tool in stable subjects will produce the same results.

15) Validity is composed of content and construct validity. The simplest definition of validity is “A measurement instrument is valid if it is measuring what it is supposed to measure.”

16) Floor and ceiling effects can be used when evaluating content validity. A high floor and ceiling effect could make distinguishing patients from each other and measuring changes in patients after intervention difficult.

17) As to construct validity, in general, an instrument has construct validity when it correlates with other measures as could be predicted.

15)

Statistical Analysis

Internal consistency was estimated using Cronbach's alpha test, which indicates homogeneity among items within a questionnaire. A Cronbach's alpha value ranging from 0.70 to 0.95 was considered adequate. To evaluate test-retest reliability, 50 patients were recruited, and the ACL-RSI Kr was administrated twice with a 1- to 2-week interval. The score was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). Content validity was assessed with ceiling and floor effects that correspond to the percentage of patients with minimum (0) or maximum (10) scores for each question. According to Terwee et al.,

18) floor or ceiling effects were considered present if > 15% of respondents achieved the lowest or highest possible score, respectively. To evaluate the construct validity of ACL-RSI Kr, correlation analysis (Pearson correlation test) was performed between ACL-RSI Kr and the other questionnaires: the correlation was strong (

r > 0.5) or medium(0.5 <

r < 0.3).

Discriminant validity was evaluated using the Return to Sports Questionnaire that was composed of four questions including time to return to sports, performance level on a 10-point Likert scale compared with the preinjury level (performance score), satisfaction score on a 10-point Likert scale. Comparison analysis between the groups divided by the score of the questionnaire was performed using Student independent t-test to determine the discriminant validity.

Go to :

RESULTS

We recruited 129 patients (102 men and 27 women) from seven institution in this study. Their mean age was 28.3 years (range, 16 to 58 years). The mean follow-up duration was 13.2 months after ACL reconstruction.

Reliability

Internal consistency was assessed by using data from 129 patients. The Cronbach's alpha value was 0.932, indicating strong internal consistency. The test-retest reliability was assessed from 50 patients who completed follow-up questionnaires. The mean interval between the two tests was 10.4 days (range, 7 to 17 days). The ICC was 0.949, indicating strong correlation (p < 0.001).

Content Validity

The floor and ceiling effects of each item ranged from 0% to 11.9% and from 5.9% to 41.5%, respectively. However, no pronounced floor effect (1.7%) or ceiling effect (3.1%) was observed.

Construct Validity

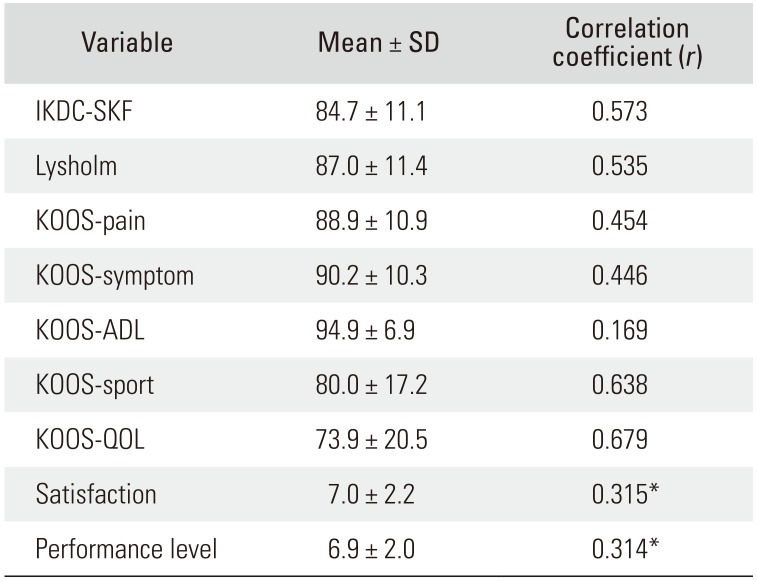

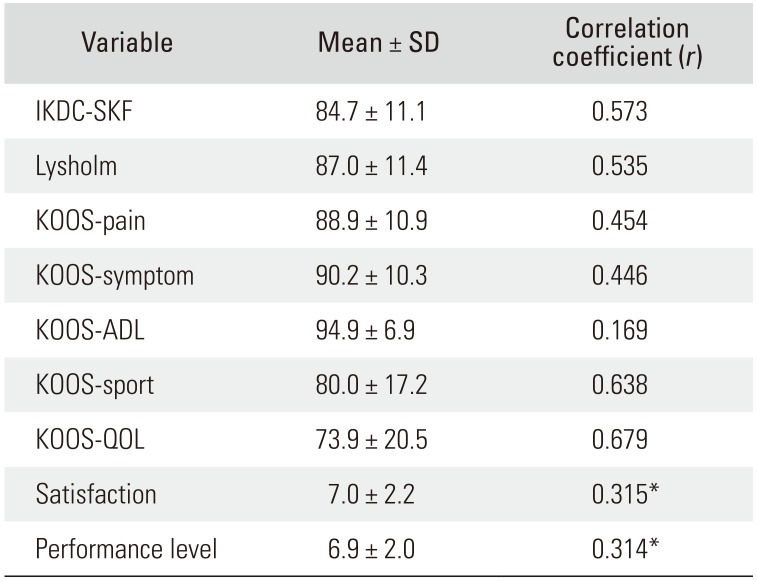

The ACL-RSI Kr had a significant positive correlation with IKDC-SKF, KOOS, Lysholm scale, satisfaction, and performance level, ranging from 0.169 to 0.679 (

p < 0.01) (

Table 1).

Table 1

Construct Validity. Pearson Correlation Test between ACL-RSI Kr and Other Questionnaires

|

Variable |

Mean ± SD |

Correlation |

|

IKDC-SKF |

84.7 ± 11.1 |

0.573 |

|

Lysholm |

87.0 ± 11.4 |

0.535 |

|

KOOS-pain |

88.9 ± 10.9 |

0.454 |

|

KOOS-symptom |

90.2 ± 10.3 |

0.446 |

|

KOOS-ADL |

94.9 ± 6.9 |

0.169 |

|

KOOS-sport |

80.0 ± 17.2 |

0.638 |

|

KOOS-QOL |

73.9 ± 20.5 |

0.679 |

|

Satisfaction |

7.0 ± 2.2 |

0.315*

|

|

Performance level |

6.9 ± 2.0 |

0.314*

|

Discriminant Validity

The ACL-RSI Kr showed significant difference between patients whose performance level was < 7 points and those whose level was ≥ 7 points (60.3 ± 27.0 vs. 72.2 ± 22.1; p = 0.025)

Go to :

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated the good psychometric properties of the ACL-RSI Kr. High reliability (good internal consistency and good test-retest reliability) was observed. In terms of validity, it showed good construct validity (moderate to strong correlations with other questionnaires) and good content validity (without ceiling or floor effects). Furthermore, it had good discriminant validity, which means the ACL-RSI Kr can be effective in distinguishing the patients who returned to sports from those who did not.

The English version of ACL RSI had good internal consistency with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.96 and good discriminant validity, shown by comparing scores between subjects who had returned to sport and those who had not yet attempted sport in a study by Webster et al.

7) They concluded that decision to return to sport after ACL reconstruction was associated with a significant psychological response, and the ACL RSI scale may help identify athletes who will find sport resumption difficult. In the present study, the ACL-RSI Kr was found to have acceptable psychometric properties comparable to the English version.

Several studies reported on the results of translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the ACL-RSI. The Turkish version of ACL-RSI was validated in 91 patients who underwent ACL reconstruction and showed good psychometric properties. It showed significant correlation with the QOL subdomain of the KOOS (KOOS-QOL) (

r = 0.58).

10) The French version of ACL-RSI also showed good measurement properties. The study included 98 subjects and 91 subjects in the control group and patient group, respectively. The French version showed strong correlation with KOOS-QOL and good discriminant validity between the patient and control groups.

3) In a Swedish version tested on 182 patients, good face validity, internal consistency, low floor and ceiling effects, and high construct validity were shown.

The ACL-RSI Kr showed a strong correlation with the KOOS-QOL (r = 0.679, p < 0.001). KOOS-QOL is composed of awareness of knee problem, confidence, difficulty, and life modification to avoid knee damage to assess the overall psychological status of a patient. The ACL-RSI is composed of three subdomains: emotions, confidence in performance, and risk appraisal. Therefore, it is expected that the ACL-RSI Kr will have a stronger correlation with the KOOS-QOL than the other subdomains of KOOS. The correlation coefficient with KOOS-QOL was 0.718, 0.58, and 0.64 in the Swedish, Turkish, and French versions, respectively.

The ACL-RSI Kr could distinguish patients who had returned to sports to a certain level (7 of 10 Likert scale) compared with the previous status from those who did not. In the English version development study, Webster et al.

7) divided the subjects into four groups: those who had given up sports and those who had planned to return to sport, training only, or full competition. Those who had given up sports showed significantly lower scores than the other three groups did, whereas those who had planned to return to full competition showed significantly higher scores than the other three groups did, indicating the scale had good discriminant validity. A Turkish version also showed good discriminant value, wherein significant differences were found between patients who returned to sports and those who did not.

10) In the French version study, discriminant validation analysis showed that a highly significant difference was found between the patient and control groups and between those who returned to the same sport before their injury and those who did not.

3)

The ACL-RSI Kr will help Korean clinicians to decide whether patients are ready to return to sports psychologically and to detect those who need psychological intervention. The importance of psychological readiness and confidence, as well as that of the functional and physical status, should not be underestimated to promote patient's successful return to sports.

This study has some limitations. If we had administered the questionnaire repeatedly with an interval, we could have assessed the responsiveness of the ACL-RSI Kr, which indicates the ability of an instrument to detect clinically important treatment effects. In addition, if we had recruited more patients, we could have performed subgroup analysis according to the different clinical settings.

In conclusion, the ACL-RSI Kr demonstrated good psychometric properties. We suggest that the ACL-RSI Kr is an excellent instrument for evaluating psychological factors in determining return to sports in patients with ACL injury.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download