Abstract

We report a case of difficult endotracheal intubation in a patient with tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica. A 65-year-old man was scheduled to undergo ulnar nerve decompression and ganglion excisional biopsy under general anesthesia. During induction of general anesthesia, an endotracheal tube could not be advanced through the vocal cords due to resistance. A large number of nodules were identified below the vocal cords using a Glidescope® video-laryngoscopy, and fiberoptic bronchoscopy revealed irregular nodules on the surface of the entire trachea and the main bronchus below the vocal cords. Use of a small endotracheal tube was attempted and failed. a laryngeal mask airway (LMA Supreme ™) rather than further intubation was successfully used to maintain the airway.

One of the most important roles for anesthesiologist is to keep the airway open according to airway management procedure even in unexpected difficult intubation.Airway management failure has fatal consequences for the patient, resulting in hypoxic brain injury and death within minutes. The American Society of Anesthesiologists defines a difficult airway as a clinical situation in which a conventionally trained anesthesiologist experiences difficulty with face mask ventilation of the upper airway, difficulty with tracheal intubation, or both, and provides recommendations for the situation.1 There are many factors associated with difficult airway management. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica (TO) is one of the rare conditions with non-specific symptoms resulting in difficult tracheal intubation. We report a case of TO found incidentally and proven as a cause of unexpected difficult intubation.

A 65-year-old man was diagnosed with right ulnar nerve palsy and ganglion and was scheduled to undergo ulnar nerve decompression and ganglion excisional biopsy under general anesthesia. He had no history of dyspnea, hemoptysis, chronic cough, or fever. His past medical history and family history was unremarkable. He was a life time non-smoker with no known occupational exposure. No abnormalities were found on preoperative laboratory test, electrocardiography and chest X-ray.

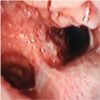

For anesthesia induction, glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg was administered intramuscularly and famotidine 20 mg was administered intravenously 30 minute before operating room. Non invasive arterial blood pressure, electrocardiography and pulse oxymetry were monitored at arrival at operating room. Preoxygenation for 4 min, then propofol 2 mg/kg, rocuronium 0.6 mg/kg, fentanyl 50 µg was administered for anesthesia induction. After 2 minutes, intubation was attempted under direct laryngoscope using an endotracheal tube with a diameter of 7.5 mm. The vocal cords were easily identified, but the endotracheal tube could not proceed below the vocal cords. After mask ventilation, intubation was attempted again with a 7.0 mm tube, but this tube could also not pass below the vocal cords. A large number of nodules were identified below the vocal cords using a Glidescope® video-laryngoscopy (Verathon, Seattle, WA). Intubation was attempted again using an endotracheal tube with a diameter of 6.5 mm and 6.0 mm in sequential order, but could not pass through the vocal cords. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy revealed irregular nodules on the surface of the entire trachea and the main bronchus below the vocal cords (Fig. 1, 2). Despite the repeated failure of tracheal intubation, there was not airway swelling and bleeding and mask ventilation was not difficult. Because the mask ventilation was not difficult, the oxygen saturation did not decrease below 95 % during tracheal intubation and fiberoptic bronchoscopy. And blood pressure and heart rate were increased to within 20 % of the baseline but remained stable without any medication. A laryngeal mask airway (LMA Supreme ™, Teleflex, Morrisville, NC) was immediately used for airway maintenance. After confirming appropriate ventilation, anesthesia was maintained with 2–3% of sevoflurane.

After surgery, extubation was conducted following the patient's complete recovery of consciousness and spontaneous respiration. The patient was transferred to the general ward without any complications in the post-anesthetic care unit. After being referred to the Respiratory Division, the patient was diagnosed with TO and underwent follow-up without any special treatment.

TO is a rare benign disease characterized by the formation of bony or cartilaginous tissue within the submucosa of the trachea and the larger bronchi. The first gross finding was described by Rokitansky in 1885 and histologic findings were described by Wilks, a doctor at Guy's Hospital, in 1857, following an autopsy of a 38-year-old man who died of tuberculosis. Muckleston in 1909 and Aschoff in 1910 named the condition tracheopathia osteochondroplastica.2 In 1964, Secrest et al.3 expanded the range to the bronchus and changed the name to TO.

The pathophysiology of TO is currently unknown. There are some hypothesis, but no objective data support these hypotheses.

Most of the cases are asymptomatic and only 51% of patients discover the disease by themselves.3 There are no clinically distinctive symptoms or signs. The most common symptoms are chronic cough, hemoptysis, chronic sputum, wheezing, hoarseness, and dyspnea.4

Before the development of bronchoscopy, TO was mainly found by autopsy. Recently, endoscopy, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging have made it easier to detect TO before death. The fiberoptic bronchoscopy finding is characterized by the presence of multiple osteocartilaginous calcified nodules within the submucosa of the anterior and lateral, but not the posterior surfaces of the tracheobronchial tree.5 Leske et al. reported that the nodules were also distributed on the posterior surface.6 Computed tomography is useful in the diagnosis of TO, as it allows identification of calcified and non-calcified nodules.7 Chest X-ray shows normal findings in most cases, but in some cases, calcification of the airways is observed.8

In general, TO can only be managed conservatively conservatively if the patient has no symptoms. treatment for patients with symptoms is focused on preventing respiratory tract infections or treating any associated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, and bronchiectasis. If tracheal or bronchial stenosis has progressed, surgical treatment (tracheal resection or laryngectomy) and bronchoscopic treatment (curettage biopsy, laser resection, and cryosurgery) may be attempted.4 According to the results of follow-up of 41 patients, 76% had chronic or recurrent symptoms, one of whom died of sepsis due to pulmonary disease.6 Another patient with severe tracheal stenosis was reported to have received ventilator care after tracheal resection and anastomosis.6

In relation to anesthesia, it is difficult to predict airway abnormalities based on preoperative examination or clinical symptoms because TO is mostly asymptomatic. It is rare to experience a difficult airway intubation in asymptomatic TO patients, with only one case reported in Korea.9 In a similar case, endotracheal intubation was successfully performed using an endotracheal tube with a diameter of 6.5 mm,9 however, in the present case, using endotracheal tubes with diameter ranging from 7.5 mm to 6.0 mm was unsuccessful. Even with smaller diameter tubes, intubation would have been difficult due to the large number of nodules.

Although a size 4.0 microlaryngoscopy tube was eventually passed over a bougie that had been placed via a rigid bronchoscope in another case report,10 we did not attempt to use a smaller endotracheal tube due to the risk of iatrogenic airway trauma or air leakage when the cuff was inflated. Because mask ventilation was adequate, an alternative intubation approach was considered according to the difficult airway management guidelines.1 Firstly, the nodule under the vocal cord was identified using a Glidescope, and the extent and internal diameter of the trachea was determined using fiberoptic bronchoscopy. We then decided to use a laryngeal mask airway to maintain anesthesia. There is no report on using laryngeal mask airways for maintenance of anesthesia, as in the present case.

In conclusion, it is advisable to use smaller diameter tubes when endotracheal intubation fails repeatedly in unexpected difficult intubation situations, but the airway evaluation using fibroptic bronchoscopy should be given priority with the possibility of TO. A laryngeal mask airway should be considered the first choice for adequate airway management in a patient with TO. It can be useful for TO if anesthesia can be maintained using such a mask.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Apfelbaum JL, Hagberg CA, Caplan RA, Blitt CD, Connis RT, Nickinovich DG, et al. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task force on management of the difficult airway. Anesthesiology. 2013; 118:251–270.

2. Akyol MU, Martin AA, Dhurandhar N, Miller RH. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica: a case report and a review of the literature. Ear Nose Throat J. 1993; 72:347–350.

3. Secrest PG, Kendig TA, Beland AJ. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica. Am J Med. 1964; 36:815–818.

4. Nienhuis DM, Prakash UB, Edell ES. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1990; 99:689–694.

5. Magnusson P, Rotemark G. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica. Three Case Reports. J Laryngol Otol. 1974; 88:159–164.

6. Leske V, Lazor R, Coetmeur D, Crestani B, Chatté G, Cordier JF. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica: a study of 41 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2001; 80:378–390.

7. Hirsch M, Tovi F, Goldstein J, Gerzof SG. Diagnosis of tracheopathia osteoplastica by computed tomography. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1985; 94:217–219.

8. Zack JR, Rozenshtein A. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica: report of three cases. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2002; 26:33–36.

9. Seo JH, Do SH. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica detected during difficult endotracheal intubation: A case report. Anesth Pain Med. 2007; 2:102–105.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download