Abstract

Milwaukee shoulder syndrome (MSS) is a rare disease in which joints are destroyed and occurs mainly in elderly women. We describe rapidly progressive MSS with complete destruction of the shoulder joint within 2 months. An 80-year-old woman visited the outpatient clinic with shoulder pain for 2 weeks. rotator cuff tear arthropathy was diagnosed, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were prescribed. Two months later, her shoulder pain worsened without trauma. Shoulder swelling and tenderness, and arm lifting inability were observed. Complete humeral head disruption was observed by radiography. We diagnosed MSS based on the presence of serohematic and noninflammatory joint effusion, periarticular calcific deposits, and rapid joint destruction, and initiated conservative treatment. When initially treating elderly patients with shoulder arthropathy, it is advisable to perform short-term follow-up and to consider the possibility of crystal-induced arthropathy.

Several diseases have been reported to cause rapid destructive arthropathy of shoulder. Milwaukee shoulder syndrome (MSS) is a rare disease that rapidly disrupts joints by depositing calcium hydroxyapatite crystals in the joints [1]. This destructive arthropathy is characterized by pain, large joint effusion, rapid and widespread cartilage and subchondral bone destruction, and multiple osteochondral loose bodies. It occurs mainly in older woman and its mechanism is unclear. Synovial fluid analysis typically shows serohematic features and low cellularity (<1,000 leukocytes/mL). We describe a case of very rapidly progressive MSS with complete destruction of the shoulder joint within 2 months. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Jeju National University Hospital (IRB no. JEJUNUH 2018-07-013).

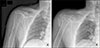

An 80-year-old woman who had no baseline disease other than hypertension visited the outpatient clinic with right shoulder pain that started 2 weeks earlier. She had no history of recent trauma to the right shoulder. Physical examination revealed tenderness of the supraspinatus muscle and biceps tendon area as well as right shoulder impingement, and Jobe's test result was positive. Plain radiography of the right shoulder showed signs of degenerative arthritis, such as subacromial space narrowing, upward migration of the humeral head, and sclerotic changes beneath the surface of the acromion (Figure 1A). Two months later, she visited the clinic with aggravated pain and a sensation of dislocated shoulders. Swelling and tenderness of the right shoulder were noted on physical examination. Radiography and computed tomography showed complete destruction of the humeral head with joint space narrowing, and erosion of the glenoid (Figure 2). Additionally, a large soft tissue swelling with extensive amorphous calcifications was observed (Figure 1B). Blood examination revealed a white blood cell count of 8,800/mm3 (segmented neutrophil 83.8%); hemoglobin, 8.4 g/dL; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 37 mm/hr; C-reactive protein, 5.7 mg/dL; alkaline phosphatase, 324 U/L; and aspartate aminotransferase, 23 IU/L. Approximately 70 mL of serohematic fluid was aspirated by joint puncture. The synovial fluid analysis showed a white blood cell count of 108/µL (polymorphonuclear leukocytes: 77%, lymphocytes: 4%, mononuclear cells: 18%, and basophil cells: 1%) and many erythrocytes. The result of the Gram stain was negative; no organisms were cultured, and the result of the cytology analysis was negative. No crystals were observed by polarizing microscopy.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a large amount of fluid collection and bone debris in the glenohumeral joint; total collapse of the humeral head, humeral neck, and glenoid scapula; and tears at the rotator cuff, biceps, and tendons (Figure 3). MSS was diagnosed, and her pain improved with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and physiotherapy. Total humeral replacement was considered, but she refused this procedure.

Two years later, radiography showed destruction of the humeral head, but the amorphous calcification had disappeared and soft tissue swelling had decreased (Figure 4).

The term “Milwaukee shoulder syndrome” was first used in 1981 to describe four elderly women in Milwaukee, in the state of Wisconsin, United States, who presented with recurrent bilateral shoulder effusion, radiographic evidence of severe destructive alterations in the glenohumeral joint, and massive rotator cuff injuries [2]. MSS is a rare clinical entity that is a rapid destructive shoulder arthropathy associated with deposition of calcium hydroxyapatite crystals. The pathogenesis of MSS is unclear, but the reported factors include trauma and joint overuse, calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition disease, cervical neuropathy due to syringomyelia or severe spondylosis, prolonged dialysis, and hyperparathyroidism [13]. Most reported cases of MSS occurred in women aged older than 80 years. Joint fluid shows serohematic or hemorrhagic appearance and non-inflammatory pattern (usually <1,000/mL leukocyte) [4]. The radiologic examination shows narrowing of the glenohumeral joint, bone sclerosis, destruction of subchondral bone and osteophytes, capsular and soft tissue calcification, and intraarticular loose bodies [456]. MRI additionally shows rotator cuff tears and cartilage thinning [7].

Initially, our patient had no abnormal findings other than a slight limitation of range of motion in the right shoulder. Radiologic findings showed slight joint space narrowing and upward migration of the humeral head. Therefore, rotator cuff arthropathy was suspected, and NSAIDs were prescribed. Two months later, she visited the emergency room with aggravated pain and the sensation of dislocated shoulders. The humeral head had completely disappeared on the plain radiograph.

There are several diseases that can cause destructive shoulder arthropathy. Trauma, gout, and CPPD were easily distinguished by history taking and examinations. There were no bacteria or malignant cells in the joint fluid examination; therefore, septic arthritis and malignant tumors were excluded. Hereditary hemochromatosis (HH) and acromegaly can cause severe disability of shoulder. However, they were excluded in this patient because she had no symptoms associated with HH and was much older than a typical HH patient, and she did not have characteristic cartilage overgrowth and thickening of soft tissues that is observed at the early stages of acromegaly [89]. Diffuse tenosynovial giant cell tumor is locally aggressive and can also involve shoulder joints [10]. Our patient had no features suggestive of synovial proliferation on physical examination and imaging studies. Neuropathic arthropathy (Charcot's arthropathy) is caused by neurological deficits and is characterized by low grade pain with rapid progression and can cause disability or deformity of the shoulder joints within months [1112]. Our patient had no history of disease associated with neuropathic arthropathy and had complaints of sesevere shoulder pain. Amyloid arthropathy involves the shoulder joint most frequently and resembles inflammatory arthritis but it was excluded because as there was no evidence of amyloid deposits on her shoulder such as a “shoulder pad” sign on physical examination and no amyloid deposition was observed on an MRI [13].

There have been some reports of MSS, but no case noted complete joint destruction within two months. In our case, we could not observe a crystal clump called “shiny coins” on plain light microscopy or a characteristic “halo” on alizarin red s staining [614]. However, we determined that the possibility of MSS was the highest, because the joint fluid was serohematic with no inflammatory findings, and radiography showed rapidly progressing joint destruction, periarticular calcification, multiple intra-articular calcified loose bodies, and destruction of the subchondral bone.

As in our case, MSS treatment is generally conservative, NSAIDs or colchicine are effective for symptom control, and joint fluid aspiration may be helpful if there is a large amount of effusion. When the joint is severely damaged, the patient may consider arthroplasty, but in our case, the patient refused the operation [56].

Many elderly patients visit the hospital due to shoulder pain. In most cases, this symptom is caused by joint degeneration. Thus, most patients are prescribed NSAIDs over the long term. However, as observed in our case, crystal-induced arthropathy may cause joint destruction within a short period of time. Hence, performing short-term follow-up and considering the possibility of crystal-induced arthropathy may be helpful in the early stages of treating shoulder pain in the elderly.

Various diseases can cause destructive shoulder arthropathy. Our case report describes an 80-year-old woman who visited with shoulder pain for 2 weeks. At first, she was diagnosed with rotator cuff tear arthropathy due to tenderness of the supraspinatus muscle and biceps tendon area on the physical examination, and high-riding humerus on radiography. Two months later, she visited with shoulder pain, edema, and feeling of shoulder dislocation. Radiographs showed complete destruction of the humeral head. Although we could not confirm calcium hydroxyapatite crystals, there was no suspicious abnormality indicating other destructive shoulder arthropathies, and Milwaukee shoulder syndrome was diagnosed because of serohematic and non-inflammatory joint fluid and appropriate imaging findings. In elderly patients, shoulder pain is most commonly caused by joint degeneration, but it is preferable to consider the possibility of crystal-induced arthropathy with short-term follow-up at the early stages of treatment.

Figures and Tables

| Figure 1(A) At first visit, the radiograph shows subacromial space narrowing and upward migration of humeral head, at the first visit. (B) Two months later, the radiograph shows extensive soft tissue swelling with extensive amorphous calcifications, complete destruction of the humeral head with cephalic migration, joint space narrowing, and erosion of the glenoid. |

| Figure 2Computed tomography shows complete destruction of the humeral head and erosion of the glenoid. |

| Figure 3Magnetic resonance imaging shows a large amount of fluid collection (red arrows) and bone debris (blue arrows) in the glenohumeral joint, total collapse of the humeral head and neck (white arrows) and glenoid (green arrow) of scapula and tears of the rotator cuff and rupture of biceps tendon (yellow arrows). |

References

2. McCarty DJ, Halverson PB, Carrera GF, Brewer BJ, Kozin F. “Milwaukee shoulder”--association of microspheroids containing hydroxyapatite crystals, active collagenase, and neutral protease with rotator cuff defects. I. Clinical aspects. Arthritis Rheum. 1981; 24:464–473.

3. Rood MJ, van Laar JM, de Schepper AM, Huizinga TW. The Milwaukee shoulder/knee syndrome. J Clin Rheumatol. 2008; 14:249–250.

4. Santiago T, Coutinho M, Malcata A, da Silva JA. Milwaukee shoulder (and knee) syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2014; 2014:pii: bcr2013202183.

6. Forster CJ, Oglesby RJ, Szkutnik AJ, Roberts JR. Positive alizarin red clumps in Milwaukee shoulder syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2009; 36:2853.

7. Llauger J, Palmer J, Rosón N, Bagué S, Camins A, Cremades R. Nonseptic monoarthritis: imaging features with clinical and histopathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2000; 20 Spec No:S263–S278.

8. Sahinbegovic E, Dallos T, Aigner E, Axmann R, Manger B, Englbrecht M, et al. Musculoskeletal disease burden of hereditary hemochromatosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010; 62:3792–3798.

10. Takeuchi A, Yamamoto N, Hayashi K, Miwa S, Takahira M, Fukui K, et al. Tenosynovial giant cell tumors in unusual locations detected by positron emission tomography imaging confused with malignant tumors: report of two cases. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016; 17:180.

11. Wakhlu A, Wakhlu A, Tandon V, Krishnani N. “Smouldering conditions of the shoulder” lest we forget. Indian J Rheumatol. 2017; 12:169–174.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download