Abstract

Background

Quality ratings could provide vital information to help people in choosing a nursing home.

Methods

We employed a cross-sectional descriptive design to assess publicly available data on 1,354 nursing homes with 30 or more beds in the Republic of Korea. After excluding 289 nursing homes with no reported quality-evaluation ratings, we analyzed the 2015 data of 1,065 nursing homes. To prevent multicollinearity among independent variables, we carefully selected the final set of variables based on clinical and theoretical meaningfulness to direct nursing care. Quality, the ordinal outcome, was scored from 1 to 5 with a higher score indicating higher quality of the organization. We constructed a multivariate ordered logistic regression model.

Results

Higher quality ratings of nursing homes was significantly related to the number of unoccupied beds (OR=0.99, p=.024), registered nurses (RNs) (OR=1.30, p=.003), qualified care workers (OR=1.03, p=.011), cognitive-improvement programs (OR=1.05, p=.024), and other programs for residents' activities (OR=1.09, p<.001).

Conclusion

The number of RNs had the strongest influence on the publicly reported quality rating, while the rating of qualified care workers demonstrated little effect and that of nursing assistants had no effect. The number of RNs could be used as a crucial indicator for high-quality homes; more resident-engaging programs also demonstrated better quality of nursing home care.

Public reporting of organizational performance in healthcare rests on the expectation of promoting an organization in the marketplace with the belief that the information will encourage consumers to choose high-quality providers [1]. Quality information for nursing home customers has become available in many countries, including the U.S. [234], Germany [5], and the Republic of Korea [6]. Publicly reporting the quality of an institution is a commonly used strategy to provide public access to publicly available information, enabling healthcare consumers to choose a high-quality provider, and to induce health-care providers to invest in and improve the quality of care they are delivering [4]. Making quality or performance information available to the public can be a powerful strategy to regulate nursing homes, ensure their quality, and help customers judge the best place to receive care [1].

On July 1, 2008, The Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare (KMHW) initiated long-term care insurance in Korea [7]. Following its enactment, the number of long-term care service providers rapidly increased along with the number of long-term care facilities [8]. The National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) operates a consumer-information system for long-term care insurance, long-term care service providers, and beneficiaries, providing information to the public [9]. This system helps all beneficiaries and their family members who seek nursing home care or personal assistance due to geriatric disease such as cardiovascular disorder, dementia, or Parkinson's disease. Because major financial revenue comes from governmental subsidies, enrollees' monthly premiums, and copayments by long-term care service users [10], maintaining affordable levels of quality care for vulnerable people and offering credible provider information is paramount to the success of the long-term care insurance system in Korea.

Based on the Long-Term Care Insurance Act 54, the KMHW inspects every nursing home every 2 years [1112]. The purpose of inspection is to improve the performance of each nursing home to ensure residents' quality of life and to ensure beneficiaries have the right to know and be able to choose their institution based on public disclosure of evaluation results [111213]. As of 2018, a total of 4 evaluations have been performed since 2009 in Korea [13]. In 2015, the evaluation cycle was changed from every 2 years to every 3 years, and the evaluation method was changed from a relative evaluation to an absolute evaluation [1415].

Public release of nursing-home evaluation results is a politically effective means of stimulating healthcare providers to improve resident care, and simultaneously gives long-term care consumers the ability to make informed choices when selecting a nursing home [2]. By reflecting on consumers' needs, long-term-care providers work to provide optimal care and maintain a greater portion of the market share [3]. The NHIS performs an unscheduled inspection when a nursing home has had negative evaluation results [9]. The NHIS [7] maintains a website entitled “Long-Term Care Insurance,” that publishes comprehensive information and ranks results of all nursing home evaluations on every nursing home in Korea. Despite the autonomy and independence of each participating nursing home, evaluation results from the website provide sufficient information about the evaluation process and the objective standards of evaluation [9]. The NHIS [7] announces the results of the evaluations to customers, aiming to improve the quality of care in Korea. Additionally, the organization provides financial incentives only to the top 20.0% of nursing homes [7].

In the U.S., to identify substandard nursing homes, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services initiated the Nursing Home Quality Initiative of 2001 [4]. Beginning in 2002, the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) released information about staffing and quality measures for all Medicare- and Medicaid-certified nursing homes [2]. Korea is in the process of adding more specific and comprehensive information about quality indicators, modeled on the U.S. CMS. The Nursing Home Compare website, provided by the U.S. CMS, publishes 19 specific quality-outcome measures (based on the Minimum Data Set 3.0 and Certification and Survey Provider Reporting data) to help customers make informed choices and provide evidence of costs for insurers [16].

The impact of public reporting is not consistent across factors. Some researchers reported nursing home performance improvements in the areas of pain management [2417], use of restraints [17], and rate of pressure ulcers [17]. In contrast, after initiating public reporting for quality measures, no statistically significant improvements emerged in areas such as daily-living activities, infection rates [217], or changes in delirium or walking [4]. When choosing nursing homes, residents at high risk for disease or injury are more likely to be influenced by the ratings than residents with low risk [4]. Some researchers reported that the information provided about nursing homes was helpful for short-stay nursing home residents [3], while others reported the information did not address the diverse demands of nursing home consumers including family members, insurers, and employers [18]. Additionally, public reporting has been effective in the copayment of long-term care service customers, which means consumers are more likely to use public reporting in the highly competitive nursing home market [19].

Furthermore, it is unclear whether the release of evaluation results has any effect on performance outcomes or patients' selection of nursing homes in Korea. To understand the complex mechanism of evaluating nursing home outcomes, we inquired about whether certain factors are significantly related to publicized quality ratings in the selection of a nursing home; these included healthcare providers' professional levels, organizational factors, whether the number of residents moderates the relationship between factors and ratings, and nursing-staff levels. This study aimed to investigate the factors predicting the publicly reported quality levels in Korean nursing homes.

We conducted a secondary data analysis using publicly available data [6] to investigate the relationships between nursing home factors and quality ratings. The unit of analysis was the nursing home. The study population was all nursing homes officially registered in South Korea that provide long-term care. The KMHW evaluated all nursing homes officially operating in South Korea by the end of December 2014 [11]. We collected the first quality-rating data evaluated from June to December 2013, released to the public in March 2015 on the website for this study, and collected organizational and structural variables and staffing data in February 2014 based on the first author's initial research project. We inspected 93.9% of all facilities in Korea (3,664 of 3,900) [12]. All nursing homes, a total of 1,354, currently operating in Korea with 30 or more beds were included for analysis. After excluding 289 nursing homes because no reports existed on quality evaluations, we included 1,065 nursing homes in the data analysis. We limited nursing home size to 30 or more beds because the organizational characteristics of large nursing homes are different from those of small nursing homes (called group homes in Korea), based on size, staffing, financing, and group activities. The Institutional Review Board of S University approved this study on April 20, 2015 (SNUIRB No. E1504/002-001).

We investigated organizational characteristics of nursing homes by nursing home size and characteristic (the number of officially approved beds), the number of current residents, total beds, unoccupied beds, waiting lists, and direct-care staffing levels. We addressed direct-care staffing levels by the numbers of registered nurses (RNs), nursing assistants, physical therapists, occupational therapists, and qualified care workers (equivalent to Certified Nurse Aides in U.S. nursing homes); we also assessed doctors' staffing, the number of full-time medical doctors (MDs), and visiting (part-time) MDs. We examined care-process measures by the number of cognition-improvement programs, physical-exercise-supporting program, and other programs. All nursing homes should at least consult with a visiting doctor, and qualified care workers undertake activities of daily living tasks for nursing home residents.

The KMHW evaluated the quality of each nursing home between June 17 and November 30, 2013: rated its quality; and publicly released that information. The five-level quality grade ratings (1~5) were coded with higher scores representing better quality. The quality evaluation has the following five dimensions: (a) facility operation (22 items, score 28, weight 20), evaluating how nursing homes operate appropriately to maintain the welfare and education of in-home staff; (b) environment and safety (22 items, score 29, weight 20), investigating the safety of equipment and facilities, the coping system in emergency situations, the living environment, and the risks of long-term care recipients; (c) human rights and accountability (10 items, score 12, weight 8), examining whether caregivers recognize and respect care recipients' rights and nursing homes are being managed ethically; (d) reimbursement process (38 items, score 58, weight 42), assuring recipients receive long-term care benefits efficiently and effectively; and (e) care outcomes (6 items, score 12, weight 10), in which the inspector evaluates residents' satisfaction with the nursing home and their improvement in daily-activity functions, dependency levels, and current morbidities. After summing all items with the weighted score, the nursing home receives a total score of 100 if it achieved all items. Based on the comprehensive quality score of each home, the top 10.0% of nursing homes received A (High Excellence), scored as 5; the next 10.0% received B (Excellent), scored as 4; the next 50.0% received C (Good), scored as 3; the next 20.0% received D (Normal), scored as 2; and the bottom 10.0% received E (Poor), scored as 1.

We conducted data analysis using STATA 15.0. We used ordinal logistic regression because of its ordinal outcome (coded from 1 to 5). First, we identified highly correlated relationships among the independent variables using pairwise correlation analysis. To avoid multicollinearity problems in the regression model, one of two highly correlated variables with a correlation coefficient of 0.85 and higher were excluded in the final model [20]. After excluding highly correlated variables, we carefully selected 12 variables that were clinically and theoretically meaningful to direct nursing care for the final multivariate-ordered logistic regression model to explore nursing-related predictors associated with the ratings of nursing homes.

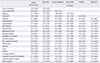

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics of all participating nursing homes. The average number of total beds was 74.12 (SD=36.07), and the average number of current residents was 63.96 (SD=33.18). The mean number of total staff was 40.03 (SD=20.20). The average number of RNs was 0.97 (SD=1.61), ranging from 0 to 19, whereas the mean number of certified nursing assistants (CNAs) was 2.12 (SD=1.29). The average number of qualified care workers was 26.80 (SD=14.10). The average number of cognition-improvement programs was 2.46 (SD=2.97), with physical-exercise programs at 0.92 (SD=1.52) and other activity programs averaging 2.53 (SD=3.58).

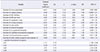

We first included all variables conducting the pairwise correlations presented in Table 1, including independent variables and outcomes but excluding occupancy rate because it is a proportion, using total beds as a denominator (see Table 2). High correlations emerged between numbers of total staff and total beds (r=.91), qualified care workers and total beds (r=.93), qualified care workers and current residents (r=.99), total staff and current residents (r=.98), and total staff and qualified care workers (r=.99) with p-values less than .001. Based on the correlation findings, we included 12 variables in the final multivariate model (see Table 3).

The most influential variable was the number of RNs (OR=1.30; p=.003). One more nurses in a nursing home aligned with 1.30-times higher quality ratings. One more qualified care worker increased quality ratings 1.03 times (p=.011). Cognition-improvement programs were significant factors in quality ratings (OR=1.05, p=.024), and the number of other activity programs was also a significant predictor of quality ratings (OR=1.09, p<.001). When one more other-activity program was operated in a nursing home, the quality rating score rose to 1.09 times higher. The number of unoccupied beds was the only factor that decreased quality ratings significantly (OR=0.99, p=.024).

First, in this cross-sectional study, we explored the direct-care-related predictors associated with quality ratings of nursing homes for all freestanding nursing homes in Korea. Our regression findings demonstrated the importance of RNs compared with CNAs, consistent with previous research [21222324]. Among the healthcare providers, the number of RNs was the strongest predictor of nursing home quality reporting; one more RN predicted 1.3 times higher quality report scores followed by care workers (1.03 times). Full- and part-time visiting physicians did not affect quality ratings. These findings were consistent with other studies that investigated the relationship between nurse staffing levels and quality indicators, showing significant alignment of facility size and nurse staffing hours with pressure ulcers after controlling for potential endogeneity for nurse staffing and activities of daily living dependency [25]. We conclude that legislation should mandate the presence of RNs in nursing homes in Korea.

Our findings provide unique and vital information on the current Korean system. A nursing home is an official healthcare organization providing nursing care to a vulnerable population who needs continuous personal assistance. Our findings support an interdisciplinary approach including various types of staff working in each nursing home. Moreover, the major finding that the numbers of RNs and care workers significantly affected the quality rating provided evidence for the notion that RNs should be mandatory in nursing homes.

Legal staffing requirements have been classified into two groups in Korea: nursing homes with more than 30 residents and those with less than 30 residents. Nursing homes in Korea must comply with and meet the human-resources standards for professional workers and organizational staff, according to the size of the nursing home. In nursing homes with more than 30 residents, one of each of the following is required: administrator, secretary general, social worker, doctor (including a doctor of Eastern medicine) or visiting physician, physical therapist, qualified care worker per 2.5 residents (one qualified care workers per two residents in a dementia-care unit), clerk, dietician, cook, hygienist, a nd c ustodian [26]. These various staff allocations should be coordinated to provide high-quality care with strong leadership from a caring workforce.

Our study illustrated that the number of activity programs, including cognition-improvement programs or other programs, was important. Recruiting more specialized personnel for programs would improve the quality of care and enhance resident activities, providing more effective management and outcome control in the organization. All nursing homes have a unique system based on their approved capacity. They must hire a competent workforce to ensure residents have healthy meals, quality care, and stimulating daily-activity programs. Our results indicate that improving the process of care is more likely to improve nursing home quality ratings than improving the structure of the organization. Each nursing home should focus on fully using the skills of staff members to operate good daily-activity programs with ample variety.

The few extant studies did not include organizational characteristics in nursing homes as important covariates. Our study demonstrated that unoccupied beds in nursing home should be considered when deciding on staffing levels to maintain a minimum level of required standard care. The lower occupancy status of total beds had a significant negative impact on quality ratings in this study, while whereas occupancy rate did not influence the technical-efficiency report in another study [27]. One may assume that the higher occupancy rate relates to a stable financial income and subsidy to provide adequate staff.

Having sufficient numbers of nurses and caregivers may expand caring time per patient day, increasing the opportunity to reveal potential risks for adverse events. The number of nurses and other coworkers determines the quality of the work environment, which aligns with the quality of care. This association exists across nursing units with different patient populations and care objectives [28]. Better work environments align with higher quality of care when controlling for various hospital and unit covariates, and this could be applied to nursing homes. This study's results strongly suggest that diversity and sufficient numbers of staff will improve actual care as well as quality ratings of nursing homes. Significant numbers of nurses would affect quality ratings, which, in turn, would influence the choices of nursing home consumers. A more specialized caring workforce is needed when homes have a large numbers of residents.

The new implementation of long-term care insurance in Korea provides more opportunities for consumers to learn about the quality of nursing home care, but only in nursing home rankings. Although public reporting of ratings improved transparency, it may have had a limited influence on consumers. In contrast, our study was the first to analyze quality ratings and factors that affected those ratings. The Korean government is working to improve the evaluation system. The nursing home market has some features that are unsatisfactory and uneven for long-term care customers, and consumers are more likely to choose long-term services with ambiguity [29]. Thus, it is crucial to have concrete and straightforward information for nursing home users and their family members.

Beginning in 2015, the evaluation system changed from a relative evaluation to an absolute evaluation to resolve the difficulty of achieving a superior grade [12]. Additionally, lower-level nursing homes require a year-round spot inspection [1215]. Even if the absolute score was not high in the 2013 evaluation, if the relative score was higher than that of other facilities of similar size, a nursing home could achieve an A or B grade. However, in 2015, an A grade required an absolute score of 90 points or more and a B grade at least 80 points [15]. As a result of the 2013 evaluation, analysts realized the average score of facility benefit dropped from 76.9 in 2009 to 75.8 in 2011 and 70.5 in 2013 [14]. As a result of the 2015 evaluations, the average score of nursing home long-term care institutions was 73.8 points, an improvement of 3.3 points [12]. Concrete information about grade results, like the five-star rating in the U.S., is necessary for consumer decision making and involvement in nursing care. U.S. nursing home consumers required more information about the policies, nursing home staff, nursing care, cultural issues, and responses from residents or family members, which are provided on the Nursing Home Compare Website [30]. In Korea, we also need to provide more information to help Koreans or immigrants to Korea choose the best-fitting nursing home.

We showed that increasing staff and programs would improve nursing home quality for consumers. These measures may more directly assist potential nursing home consumers. Thus, we propose several recommendations for Korean Long-Term Care Insurance to enhance long-term care services. Specific information on suitable quality indicators and attributes for choosing nursing homes should be available to customers. Current available information on the website does not include basic quality-of-care indicators like prevalence of falls or use of restraints. Furthermore, the website should provide concrete, user-friendly terms for customers [31] because many consumers will not understand the clinical attributes of care reporting (prevalence of falls, weight loss, etc.) as well as general service attributes [32]. Moreover, the NHIS should provide more reliable, feasible, unbiased information about long-term care, continuously updating information that reflects consumers' opinions, providers' performance, and changing healthcare markets that affect nursing home quality of care. Currently, the NHIS only publishes evaluation ratings by KMHW experts; information provided by consumers, including satisfaction levels or experiences, should also be included in the future. We propose a combination of government and consumer ratings.

This study has several limitations. First, we collected publicly reported nursing home data from the Long-Term Care Insurance website, so the scope of variables included in our statistical models was somewhat limited. The major limitation of this study was that the outcomes of public reporting were only measured by quality ratings, whereas previous researchers discerned the effects of public reporting on specific outcomes, including pain management, use of restraints, and rate of pressure ulcers [2417]. Measures reported for administrative purposes may include intrinsic measurement errors, such as changes in staff numbers over time, after providers reported their data at a specific moment. Staffing measures should be measured as hours, not count, because staff types are not equal in the amount of time spent performing their roles and their impact on quality of care. Public reporting in South Korea still entails collecting staff information as a head count; instead, staff hours per resident day should be used for data collection in the future. Additionally, rankings were based on a one-time measurement; further research is required to examine the impact of the public release of results longitudinally. Finally, there were time lags between the period (June 2013~December 2013) in which the first quality evaluation was performed, the period (March 2015) in which quality ratings were officially released on the long-term care website, and the period (February 2014) in which the organizational factors we examined as predicting factors for this study were collected.

Additional potential endogenous process variables, including the financial status of nursing homes, their organizational culture, and interactions between residents and staff, were not included in this analysis. Long-term care providers rated as low-quality may try to report better outcomes (down-coding or not reporting some events); these false reports may place residents at greater risk [4]. Well-crafted variables theoretically designed by researchers and experts may help improve the quality of nursing home information reported by the website. Furthermore, more specific information from well-designed data structures, such as the Minimum Data Set in the U.S., would be quite helpful in detecting those factors that significantly contribute to the ratings of nursing home quality for each nursing home. Therefore, additional research that enables the dissemination of reliable information to consumers is needed in the future.

This study provides critical information on the need to consider the number of RNs as a significant marker of a high-quality nursing home. This study documented that the contribution of RNs ensures highly rated nursing homes in the first government-initiated evaluation of all operating nursing homes. The current publicly reported data structure in Korea is still not sophisticated and requires more research on the refinement of significant indicators and reporting methods. Even with the crude indicators currently reported on the public website, our findings suggested that more resident-engaging programs operating to improve cognitive skill and other programs that are not exercise-related were significantly correlated with higher-quality nursing homes in the first objective evaluation in Korea. Therefore, more resident-centered care programs and better-qualified nursing staff could be reliable indicators for those seeking a nursing home that delivers quality care.

Notes

References

1. Marshall MN, Shekelle PG, Leatherman S, Brook RH. The public release of performance data: What do we expect to gain? A review of the evidence. JAMA. 2000; 283(14):1866–1874. DOI: 10.1001/jama.283.14.1866.

2. Werner RM, Konetzka RT, Kim MM. Quality improvement under nursing home compare: The association between changes in process and outcome measures. Medical Care. 2013; 51(7):582–588. DOI: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31828dbae4.

3. Werner R, Stuart E, Polsky D. Public reporting drove quality gains at nursing homes. Health Affairs (Millwood). 2010; 29(9):1706–1713. DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0556.

4. Werner RM, Konetzka RT, Stuart EA, Polsky D. Changes in patient sorting to nursing homes under public reporting: Improved patient matching or provider gaming? Health Services Research. 2011; 46(2):555–571. DOI: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01205.x.

5. Herr A, Nguyen TV, Schmitz H. Public reporting and the quality of care of German nursing homes. Health Policy. 2016; 120(10):1162–1170. DOI: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.09.004.

6. National Health Insurance Service. Long-term care agency evaluation manual [Internet]. Wonju: National Health Insurance Service;c2015. cited 2015 Jan 30. Available from: http://www.longtermcare.or.kr/npbs/d/m/000/moveBoard-View?menuId=npe0000000770&bKey=B0009&search_boardId=50502.

7. National Health Insurance Service. Long term care insurance [Internet]. Wonju: National Health Insurance Service;c2018. cited 2018 Sep 13. Available from: http://www.longtermcare.or.kr/npbs/e/b/101/npeb101m01.web?q=C1010767189E0082F8B44831F6641647929078B842F2C3;s0ugjCW7oDVzaA2ZbGcyR4soShLbQgBUT3TCe7QhUCNRsZYo0cfyiKXeTb0gW9aN1YFUugGBRTKOuWxSDvykZA%3D%3D;aNIlpWJiykO3I0XR9hGe3bnwuFs%3D&charset=UTF-8.

8. Seon WD. Analysis of installation status of long-term care facilities for the elderly and political implication. Health and Welfare Issue & Focus. 2015; 299:1–8.

9. National Health Insurance Service. Long term care insurance. Wonju: National Health Insurance Service;c2011. cited 2018 Oct 15. Available from: http://www.longtermcare.or.kr/npbs/.

10. Kim H, Kwon S, Yoon NH, Hyun KR. Utilization of long-term care services under the public long-term care insurance program in Korea: Implications of a subsidy policy. Health Policy. 2013; 111(2):166–174. DOI: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.04.009.

11. National Health Insurance Service. Long-term care agency evaluation plan and major changes [Internet]. Wonju: National Health Insurance Service;c2015. cited 2015 Jan 30. Available from: http://www.longtermcare.or.kr/npbs/d/m/000/moveBoardView?menuId=npe0000000770&bKey=B0009&search_boardId=50502.

12. National Health Insurance Service. The evaluation result of 2015 long term care insurance [Internet]. Wonju: National Health Insurance Service;c2016. cited 2016 Apr 22. Available from: http://www.longtermcare.or.kr/npbs/d/m/000/moveBoardView?menuId=npe0000000770&bKey=B0009&search_boardId=60016.

13. National Health Insurance Service. Long-term care agency (facility benefit) periodic evaluation plan [Internet]. Wonju: National Health Insurance Service;c2018. cited 2018 Sep 13. Available from: http://www.longtermcare.or.kr/npbs/d/m/000/moveBoardView?menuId=npe0000000770&bKey=B0009&search_boardId=60221.

14. Ha HS. Evaluation for long-term care for the elderly [Internet]. Seoul: National Assembly Budget Office;c2015. cited 2015 Sep 14. Available from: https://www.nabo.go.kr/Sub/01Report/01_01_Board.jsp?funcSUB=view&bid=19&arg_cid1=0&arg_cid2=0&arg_class_id=0¤tPage=0&pageSize=10¤tPageSUB=0&pageSizeSUB=10&key_typeSUB=subject&keySUB=%EC%9E%A5%EA%B8%B0%EC%9A%94%EC%96%91&search_start_dateSUB=&search_end_dateSUB=&department=0&department_sub=0&etc_cate1=&etc_cate2=&sortBy=reg_date&ascOrDesc=desc&search_key1=&etc_1=0&etc_2=0&tag_key=&arg_id=5622&item_id=5622&etc_1=0&etc_2=0&name2=0.

15. Yoo J. How the change in the evaluation policy affects the grade, closure, and reinstallation of long-term care facilities? Health and Social Welfare Review. 2017; 37(4):71–97. DOI: 10.15709/hswr.2017.37.4.71.

16. Medicare.gov. About nursing home compare data [Internet]. Lawrence: Medicare.gov;c2018. cited 2018 Jun 5. Available from: https://www.medicare.gov/nursinghomecompare/Data/About.html#dataSource.

17. Mukamel DB, Weimer DL, Spector WD, Ladd H, Zinn JS. Publication of quality report cards and trends in reported quality measures in nursing homes. Health Service Research. 2008; 43(4):1244–1262. DOI: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00829.x.

18. Grabowski DC, Town RJ. Does information matter? Competition, quality, and the impact of nursing home report cards. Health Services Research. 2011; 46(6pt1):1698–1719. DOI: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01298.x.

19. Huang SS, Hirth RA. Quality rating and private-prices: Evidence from the nursing home industry. Journal of Health Economics. 2016; 50:59–70. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2016.08.007.

20. Polit DF. Data analysis and statistics for nursing research. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Appleton & Lange;1996. p. 281–284.

21. American Nurses Association (ANA). Safe staffing [Internet]. Silver Spring (MD): ANA;c2015-2018. cited 2018 Oct 6. Available from: https://ana.aristotle.com/SitePages/safestaffing.aspx.

22. Kjøs BØ, Havig AK. An examination of quality of care in Norwegian nursing homes - a change to more activities? Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2016; 30(2):330–339. DOI: 10.1111/scs.12249.

23. Shin JH. Relationship between nursing staffing and quality of life in nursing homes. Contemporary Nurse. 2013; 44(2):133–143. DOI: 10.5172/conu.2013.44.2.133.

24. Shin JH, Hyun TK. Nurse staffing and quality of care of nursing home residents in Korea. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2015; 47(6):555–564. DOI: 10.1111/jnu.12166.

25. Lee HY, Blegen MA, Harrington C. The effects of RN staffing hours on nursing home quality: A two-stage model. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2014; 51(3):409–417. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.10.007.

26. Korea Ministry of Government Legislation. Long term care insurance law [Internet]. Sejong: Korea Ministry of Government Legislation;c2019. cited 2018 Sep 14. Available from: http://www.law.go.kr/lsSc.do?tabMenuId=tab18&query=%EB%85%B8%EC%9D%B8%EC%9E%A5%EA%B8%B0%EC%9A%94%EC%96%91%EB%B3%B4%ED%97%98%EB%B2%95#undefined.

27. Min A, Park CG, Scott LD. Evaluating technical efficiency of nursing care using data envelopment analysis and multilevel modeling. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2016; 38(11):1489–1508. DOI: 10.1177/0193945916650199.

28. Ma C, Olds DM, Dunton NE. Nurse work environment and quality of care by unit types: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2015; 52(10):1565–1572. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.05.011.

29. He D, Konetzka RT. Public reporting and demand rationing: Evidence from the nursing home industry. Health Economics. 2015; 24(11):1437–1451. DOI: 10.1002/hec.3097.

30. Hefele JG, Acevedo A, Nsiah-Jefferson L, Bishop C, Abbas Y, Damien E, et al. Choosing a nursing home: What do consumers want to know, and do preferences vary across race/ethnicity? Health Research and Educational Trust. 2016; 51:Suppl 2. 1167–1187. DOI: 10.1111/1475-6773.12457.

31. Groenewoud AS, van Exel NJA, Berg M, Huijsman R. Building quality report cards for geriatric care in the Netherlands: Using concept mapping to identify the appropriate “building blocks” from the consumer's perspective. The Gerontologist. 2008; 48(1):79–92. DOI: 10.1093/geront/48.1.79.

32. Pesis-Katz I, Phelps CE, Temkin-Greener H, Spector WD, Veazie P, Mukamel DB. Making difficult decisions: The role of quality of care in choosing a nursing home. American Journal of Public Health. 2013; 103(5):e31–e37. DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301243.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download