Abstract

Purpose

To measure the degree of physical activity among breast cancer survivors and to identify how it was influenced by social cognitive factors, as defined in Bandura's social cognitive theory.

Methods

A total of 128 breast cancer survivors were recruited for this descriptive study and answered the survey questionnaire. The collected data covered general characteristics, physical activity, and social cognitive factors, such as self-efficacy, outcome expectations, goal setting, and socio-structural factors (social support and negative impact of cancer). Data collection was conducted from July to October 2017.

Results

The degree of physical activity among breast cancer survivors was moderate. The participants' level of physical activity differed according to their Body Mass Index (BMI) and type of surgery. Physical activity was significantly correlated with exercise goal setting, exercise self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and family support. Exercise goal setting (β=.55, p<.001), BMI (kg/m2) (β=−.21, p=.003), and exercise self-efficacy (β=.15, p=.040) were identified as factors influencing physical activity.

Conclusion

Intervention programs to increase the degree of physical activity among breast cancer survivors will need to consider various aspects, including goal setting, BMI regulation, and self-efficacy improvement. Repeated studies on the social recognition of breast cancer survivors and extended studies on health promotion activities are recommended.

Owing to its high incidence, breast cancer is one of the most threatening cancers globally [1]. The rate of survival from breast cancer varies across countries, but it is generally apparent that the rate is increasing. This is due not only to the development of early diagnosis and therapeutic strategies but also to the education of the general public on many different treatment methods. However, since 2015, breast cancer deaths have accounted for 15 percent of the world's cancer deaths [1]. When it comes to cancer recurrence, special care must be taken to reduce the risks to individual lives as well as socioeconomic loss. Consequently, it is important to promote a healthy diet, physical activity, and control of alcohol intake, overweight, and obesity as practical and adjustable preventive interventions to reduce the risk of breast cancer and the risk of relapse. Amid such lifestyle factors, physical activity has the greatest effect on breast cancer, thereby emphasizing its importance [2]. Therefore, this study was conducted to enhance physical activity in breast cancer survivors.

Bandura's social cognitive theory was developed to understand the effects of social and psychological factors on various health promotion activities, including physical activity [3]. Used as a foundation in this study, it includes self-efficacy, outcome expectations, goal setting, and facilitating/inhibiting factors [3]. Self-efficacy as defined in social cognitive theory is one's belief in the ability to successfully complete an action. Self-efficacy for health behaviors determines when one can change one's health behaviors, how much effort must be made to change one's health behaviors, and how long changes can last in the event of disabilities and failures [4]. Outcome expectations reflect a person's belief in the consequences of engaging in a particular act, and expectations increase the predictive power of how well the person behaves. Goal setting is a useful self-regulatory resource to help individuals adopt and maintain patterns of regular physical activity by guiding their actions or efforts [3]. Finally, Bandura suggested that there are socio-structural promoting/inhibiting factors in health promotion activities [3]. Consequently, the determinants of social cognitive theory can provide important clues to identify which main factors determine health behaviors.

Social cognitive theory can set a useful foundation for understanding the physical activity of breast cancer survivors and developing various programs aimed at promoting and maintaining it. While various studies have identified the relationship between social cognitive factors and physical activities, most have been limited in terms of the number of factors identified [56]. The number of studies has been limited to identify the degree of physical activities, including the various factors that make up the social cognitive theory [56]. Therefore, this study attempted to determine the effects of factors such as self-efficacy, outcome expectations, goal setting, and promoting/inhibiting factors, identified in Bandura's social cognitive theory, on the behavior of breast cancer survivors. The results of this study will lay the groundwork for various interventional programs to enhance the physical activity of breast cancer survivors.

This was a cross-sectional descriptive study that attempted to determine the factors influencing physical activity in breast cancer survivors as described in Bandura's social cognitive theory.

The participants of this study were women over the age of 18 diagnosed with breast cancer, who did not suffer from any other cancer and who had no cognitive abnormalities. A non-probability convenience sampling strategy was used to recruit participants of a breast cancer self-help group in Gwangju or Daegu city in South Korea.

Based on the G*Power 3.1.9.2 program, to include six independent variables in multiple regression analysis, a sample size of 115 was required for a sufficient power of .90 with a medium effect size of .15 [7]. Conservatively, a 10% dropout rate due to incomplete data was presumed. Thus, the number of participants initially targeted had to be a minimum of 135. Finally, after excluding six inappropriate questionnaires, the responses of 128 participants were used in the analysis.

General characteristics included those related to demographics, health, and disease. The demographic characteristics were age, educational level, current job status, and marital status. The health-related characteristics included Body Mass Index (BMI) and the current status of menopause. BMI was calculated using weight (kg) and height (m2), based on which participants were categorized as low weight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5~22.9 kg/m2), overweight (23.0~24.9 kg/m2), and obese (≥25 kg/m2) according to the Asia-Pacific standards suggested by the World Health Organization [8]. The disease-related characteristics also included family history of breast cancer, cancer stage at diagnosis, duration of diagnosis, self-examination, type of surgery and treatment, and recurrence.

With the approval of the developer, a part of the Health Promoting Lifestyle Profile-II was used to assess individual habits concerning the degree of physical activity [9]. This tool was translated according to the translation procedure of Jones and his colleagues' research [10]. Used in various studies to identify the lifestyle of breast cancer survivors [1112], it consists of eight questions scored on a four-point Likert scale; the higher the score, the higher the degree of physical activity. Cronbach's α was .85 at the time of development and .84 in this study.

Social cognitive factors comprised self-efficacy associated with physical activity, outcome expectations, goal setting, and socio-structural factors (social support and negative impact of cancer). All tools were used with the approval of the developers.

This study used the Physical Exercise Self-Efficacy Scale consisting of five questions scored on a four-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating higher self-efficacy associated with physical activity [4]. This tool was translated according to the translation procedure of this study [10]. Cronbach's α was .88 at the time of development and .86 in this study.

This study used the Outcome Expectations for Exercise Scale consisting of nine questions scored on a five-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating higher expectations of physical activity outcomes [13]. This tool was translated according to the translation procedure of this study [10]. Cronbach's α was .89 at the time of development and .84 in this study.

This study used the Exercise Goal-Setting Scale, which was translated according to the translation procedure of this study [10]. This tool consists of 10 questions scored on a five-point Likert scale; the higher the score, the more relevant the goals are to physical activity [14]. Cronbach's α was .89 at the time of development and .88 in this study.

Social support for the promoting factors was assessed using a family support tool that Tae developed for cancer patients [15]. The tool consists of eight questions scored on a five-point Likert scale; the higher the score, the higher the support. Cronbach's α was .82 at the time of development and .92 in this study.

Inhibiting factors were assessed using the Negative Impact of Cancer (version 2) [16]. This tool was translated according to the translation procedure of this study [10]. It consists of 20 questions scored on a five-point Likert scale, and higher scores indicate stronger negative impact. Cronbach's α was .91 in Smith et al.'s study [17] and .93 in this study.

Data collection was carried out from July to October 2017. The data collection was approved by the chairman of the breast cancer self-help group, after which the researcher attended a regular meeting to explain the study and distribute the questionnaire. The questionnaires were distributed to those who volunteered to participate and took 20 to 30 minutes to complete.

The Institutional Review Board of Dongyang University approved the study protocol (1041495-201612-HR-05-01). Participants were provided with explanations of the ethical aspects of the study, its purpose, and the anonymity of their data. They were informed that participation in the survey could be terminated at any time.

The SPSS/WIN 24.0 program was used for data analysis. Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests were used to test the normality of all variables, which were normally distributed. Physical activity and social cognitive factors were analyzed through descriptive statistics. The relationships between physical activity and social cognitive factors were analyzed using Pearson's correlation coefficient. The differences in physical activity according to the characteristics were assessed using independent t-tests or one-way ANOVAs and Scheffé's tests. Stepwise multiple regression analysis was used to determine the factors affecting physical activity.

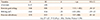

The average age of the 128 Korean breast cancer survivors was 53.2±6.32 years. The majority of the participants were in their 50s (85, 66.4%), and were high school graduates (70, 54.7%). According to the analysis of health-related characteristics, the average BMI was 22.25±2.08 kg/m2, and majority of the participants were within a normal BMI range (77, 60.2%). At the time of the study, 111 (86.7 %) had experienced menopause. According to disease-related characteristics, 64 participants (50.0%) were in the second phase of diagnosis, 68 (53.1%) were first diagnosed through self-examination, and 65 (50.8%) had undergone total mastectomy (Table 1).

Physical activity and social cognitive determinant scores are shown in Table 2. The mean score for breast cancer survivors' physical activity was 21.83±4.24 (item mean 2.73).

Differences in physical activity according to participants' characteristics were found in BMI (F=4.07, p=.008) and type of surgery (t=−2.47, p=.015). It was found that participants with a normal BMI (22.70±3.99) scored significantly higher on physical activity than did those in the obese range (18.92±2.94). Those who underwent partial mastectomy (20.90±3.78) were found to have a significantly lower score on physical activity than those who underwent total mastectomy (22.72±4.49) (Table 1).

Physical activity among breast cancer survivors was significantly correlated with goal setting (r=.62, p<.001), self-efficacy (r=.30, p=.001), outcome expectations (r=.19, p=.030), and family support (r=.19, p=.036). However, the relationship between physical activity and negative impact of cancer was not significant (Table 3).

To analyze the health promotion-related factors influencing breast cancer survivors' physical activity, a stepwise multiple regression analysis was performed with BMI (kg/m2) and type of surgery (dummy variable), which were significantly influenced by differences in physical activity according to general characteristics. The analysis also included social cognitive factors such as goal setting, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and family support, which showed a significant correlation with physical activity. The Durbin-Watson value was 1.986, supporting the assumption of independence. The tolerances of variables were all larger than .10 and ranged from .611 to .966, and the variance inflation factor values were all smaller than 10 and ranged from 1.026 to 1.117, which indicated that multicollinearity was not evident in the data.

The regression equation for physical activity was statistically significant (F=32.49, p<.001), and its explanation was confirmed to be 42.7% of the variance. The major factors affecting the behavior of breast cancer survivors were exercise goal setting (β=.55, p<.001), followed by BMI (β=−.21, p=.003) and exercise self-efficacy (β=.15, p=.040). It was found that the more appropriate the goals set, the better the performance of physical activity. Additionally, the more likely survivors were to have a lower BMI and higher self-efficacy, the better they performed physical activity (Table 4).

This study was conducted to determine the influences of the factors identified in Bandura's social cognitive theory on physical activity to promote the health behavior of breast cancer survivors.

In this study, breast cancer survivors scored an average of 21.83 points on physical activity (item mean 2.73), indicating moderate physical activity. This is similar to the results of previous studies on breast or cervical cancer survivors [1118]. However, certain studies have demonstrated that breast cancer survivors have a higher level of physical activity than middle-aged or adult women who do not suffer from cancer [1920]. Although the survival rate may have risen in part because of the increased early diagnosis rate of breast cancer and the development of treatment methods, cancer survivors have increased their awareness regarding health improvement practices. Thus, they appear to be better at taking practical precautions against relapse or deterioration than the general population before the onset of the disease.

In this study, the major factors affecting the physical activity of breast cancer survivors included goal setting, BMI, and self-efficacy. It has been found that people with proper goals, a low BMI, and a high sense of self-efficacy are the best at engaging in physical activity. First, in this study, it was found that goal setting among breast cancer survivors majorly influenced their physical activity. Some previous studies [14212223] have also demonstrated that goal setting affects physical activity, while others have identified a significant correlation between these variables [14212425]. However, in some studies, goal setting was not a significant factor in physical activity, even if there was a correlation [2426]. Despite these conflicting reports, to encourage the physical activity of breast cancer survivors, helping them set accurate targets should be a priority.

The BMI (kg/m2) of breast cancer survivors was a factor in their physical activity; the lower the BMI, the better their performance of physical activity. While it was difficult to make direct comparisons because of the lack of studies seeking to determine the degree of physical activity based on BMI, one study did demonstrate weight to be a factor in physical activity in female college students [22]. A study comparing the relationship between energy consumption and physical activity over seven days also found that the higher the consumption, the higher the physical activity [14]. Further research is needed to determine the extent to which accurate BMI affects physical activity, as well as on interventions to reduce the BMI of breast cancer survivors.

Finally, in this study, breast cancer survivors' self-efficacy was found to be a factor in their physical activity, and the higher the self-efficacy, the better their physical activity. A similar result was found in some studies [212426], which showed that self-efficacy affected physical activity. A significant correlation between physical activity and self-efficacy was also identified in various studies [414212425]. However, some studies have found that self-efficacy is not a significant factor in physical activity [2728]. Nevertheless, healthcare providers need to explore ways to improve the self-efficacy of breast cancer survivors. Although some aspects of this study do not correspond to prior studies, the results show that three factors-goal setting, BMI, and self-efficacy-have a major influence on physical activity, and interventions that take them into consideration are necessary.

In addition to the statistically significant influential factors identified above, outcome expectations related to physical activity could determine the degree of breast cancer survivors' physical activity, but they were not found to be a significant factor in performing physical activity. The correlation between outcome expectations and physical activity was similar to the findings of Rovniak et al. [14] and White et al. [25]. In addition, some studies have found that outcome expectations were not a significant contributor to the degree of physical activity, as shown in this study [26]. However, the results of previous studies were not exactly consistent with those of this study [61329].

In this study, while the social support of breast cancer survivors has a significant correlation with their degree of physical activity, this was not found to be a significant factor in the degree of physical activity they engaged in. This correlation between social support and the degree of physical activity was similar to that demonstrated by Rovniak et al. [14]. Similar to the present results, studies have shown that family support has little to do with physical activity [22242630]. However, it has been shown to have a significant effect on the degree of physical activity [21].

In this study, the negative impact of cancer was not significant in its correlation to the degree of physical activity and its influential factors. Even though it is difficult to compare the negative impact of cancer on the physical activity of breast cancer survivors, it was seen to affect the physical health of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma survivors who finished therapy [17]. It has also been found to be a contributing factor to stress symptoms among long-term survivors of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma [31]. Thus, although no prior study has identified the relevance of the negative impact of cancer on various participant characteristics or variables, it appears to be related to the health or health behaviors of cancer survivors. However, this study may have been unable to identify its impact because of the small cross-sectional sample. Therefore, further studies regarding outcome expectations, social support, and the negative impact of cancer should be conducted.

As shown above, the results of this study emphasize the need for proper body activity-related goals, reduction in BMI, and proper self-efficacy for promoting breast cancer survivors' physical activity. Therefore, before planning their physical activities, it is necessary to consider their specific characteristics. Further, it is recommended that further studies be conducted on the relationships among and factors influencing outcome expectations, social support, and negative impact of cancer that have been identified in prior studies but were not seen to have significant relationships in this study.

For intervention programs to increase the degree of physical activity in breast cancer survivors to be successful, a multilateral effort including ways to set goals, control BMI, and improve self-efficacy will be required. However, this study's results may have limited generalizability as it recruited a limited number of participants using self-help groups in Gwangju and Daegu city. There was also difficulty in finding relevant evidence, as there were few prior studies on the variables used in this study, especially the negative impact of cancer.

The results of this study show that the factors defined in social cognitive theory are major factors influencing physical activity; therefore, using social cognitive approaches and intervention to encourage health promotion activities is important. The results also suggest the need to implement a series of iterative studies that apply social cognitive theory to breast cancer survivors and the need for extended studies on health promotion activities.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

General Characteristics of Subjects and Physical Activity according to General Characteristics (N=128)

Table 2

Scores for Physical Activity and Social Cognitive Determinants among Breast Cancer Survivors (N=128)

References

1. World Health Organization. Cancer; breast cancer [Internet]. 2018. cited 2018 March 20. Available from: https://www.who.int/cancer/prevention/diagnosis-screening/breast-cancer/en/.

2. Yoo Y-G, Choi S-K, Hwang S-J, Kim H-S. Risk factors of breast cancer according to life style. Journal of the Korea Contents Association. 2013; 13(4):262–272. DOI: 10.5392/JKCA.2013.13.04.262.

3. Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior. 2004; 31(2):143–164. DOI: 10.1177/1090198104263660.

4. Schwarzer R, Renner B. Health-specific self-efficacy scales [Internet]. cited 2018 March 20. Available from: http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/health/healself.pdf.

5. McAuley E, Blissmer B. Self-efficacy determinants and consequences of physical activity. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews. 2000; 28(2):85–88.

6. Wójcicki TR, White SW, McAuley E. Assessing outcome expectations in older adults: the multidimensional outcome expectations for exercise scale. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2009; 64B(1):33–40. DOI: 10.1093/geronb/gbn032.

8. World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific. The Asia-Pacific perspective: redefining obesity and its treatment [Internet]. Sydney: Health Communications Australia;2000. Available from: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/206936.

9. Walker SN, Sechrist KR, Pender NJ. The health-promoting lifestyle profile: development and psychometric characteristics. Nursing Research. 1987; 36(2):76–81. DOI: 10.1097/00006199-198703000-00002.

10. Jones PS, Zhang XE, Meleis AI. Transforming vulnerability. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2003; 25(7):835–853. DOI: 10.1177/0193945903256711.

11. Jeong K, Heo J, Tae Y. Relationships among distress, family support, and health promotion behavior in breast cancer survivors. Asian Oncology Nursing. 2014; 14(3):146–154. DOI: 10.5388/aon.2014.14.3.146.

12. Yi M, Kim J. Factors influencing health-promoting behaviors in Korean breast cancer survivors. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2013; 17(2):138–145. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejon.2012.05.001.

13. Resnick B, Zimmerman SI, Orwig D, Furstenberg A-L, Magaziner J. Outcome expectations for exercise scale: utility and psychometrics. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2000; 55(6):S352–S356. DOI: 10.1093/geronb/55.6.S352.

14. Rovniak LS, Anderson ES, Winett RA, Stephens RS. Social cognitive determinants of physical activity in young adults: a prospective structural equation analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2002; 24(2):149–156. DOI: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2402_12.

15. Tae YS. A study on the correlation between perceived social support and depression of the cancer patients [master's thesis]. Seoul: Ewha Womans University;1986.

16. Crespi CM, Ganz PA, Petersen L, Castillo A, Caan B. Refinement and psychometric evaluation of the impact of cancer scale. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008; 100(21):1530–1541. DOI: 10.1093/jnci/djn340.

17. Smith SK, Crespi CM, Petersen L, Zimmerman S, Ganz PA. The impact of cancer and quality of life for post-treatment non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2010; 19(12):1259–1267. DOI: 10.1002/pon.1684.

18. Lee EJ. Family support, self-esteem and health promotion behavior in uterine cancer patients [dissertation]. Seoul: Chung-Ang University;2012.

19. Enjezab B, Farajzadegan Z, Taleghani F, Aflatoonian A, Morowatisharifabad MA. Health promoting behaviors in a population-based sample of middle-aged women and its relevant factors in Yazd, Iran. International Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012; 3:suppl 1. S191–S198.

20. Kim JI, Oh KO, Li CY, Min HS, Chang ES, Song R. Breast cancer screening practice and health-promoting behavior among Chinese women. Asian Nursing Research. 2011; 5(3):157–163. DOI: 10.1016/j.anr.2011.09.005.

21. Park C-H, Elavsky S, Koo K-M. Factors influencing physical activity in older adults. Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation. 2014; 10(1):45–52. DOI: 10.12965/jer.140089.

22. Choi JY, Chang AK, Choi E-J. Sex differences in social cognitive factors and physical activity in Korean college students. Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 2015; 27(6):1659–1664. DOI: 10.1589/jpts.27.1659.

23. Dishman RK, Vandenberg RJ, Motl RW, Wilson MG, DeJoy DM. Dose relations between goal setting, theory-based correlates of goal setting and increases in physical activity during a workplace trial. Health Education Research. 2010; 25(4):620–631. DOI: 10.1093/her/cyp042.

24. Mudrák J, Slepička P, Elavsky S. Motivation for physical activity in Czech seniors. Acta Universitatis Carolinae-Kinanthropologica. 2011; 47(2):7–18.

25. White SM, Wójcicki TR, McAuley E. Social cognitive influences on physical activity behavior in middle-aged and older adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2012; 67B(1):18–26. DOI: 10.1093/geronb/gbr064.

26. Haider T, Sharma M, Bernard A. Using social cognitive theory to predict exercise behavior among South Asian college students. Journal of Community Medicine & Health Education. 2012; 2(6):2–6. DOI: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000155.

27. Anderson ES, Wojcik JR, Winett RA, Williams DM. Social-cognitive determinants of physical activity: the influence of social support, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and self-regulation among participants in a church-based health promotion study. Health Psychology. 2006; 25(4):510–520. DOI: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.510.

28. Ginis KAM, Latimer AE, Arbour-Nicitopoulos KP, Bassett RL, Wolfe DL, Hanna SE. Determinants of physical activity among people with spinal cord injury: a test of social cognitive theory. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2011; 42(1):127–133. DOI: 10.1007/s12160-011-9278-9.

29. Hartono GM, Pohan LD. The motivation of health behavior: how self-efficacy and outcome expectancies impact health behavior intention of long-term cancer survivors. UI Proceedings on Social Science and Humanities. 2017; 1:1–4.

30. Lee J-R, Lee G-W, Chin E-Y, Park B-N, Son Y. The relationship among resilience, family support and health promotion of hospitalized cancer patients in an advanced general hospital. The Journal of the Korea Institute of Oriental Medical Informatics. 2015; 21(2):35–45.

31. Smith SK, Zimmerman S, Williams CS, Benecha H, Abernethy AP, Mayer DK, et al. Post-traumatic stress symptoms in long-term non-Hodgkin's lymphoma survivors: does time heal? Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011; 29(34):4526–4533. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.2631.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download